A Framework for New Essential Oil Development

Proceedings of the First Australian New Crops Conference held at The University of Queensland Gatton College 8 – 11 July 1996

Abstract

Developing new essential oils presents difficulties because researchers and primary producers generally have little knowledge of essential oil applications and markets. Australia’s isolation from the major essential oil consuming markets of Europe, Japan and the United States compounds the problem. This paper presents a system to classify essential oils according to their uses and trade characteristics. A method to evaluate the market potential of new essential oils by examining characteristic strengths and weaknesses is outlined. Opportunities for new essential oil development are considered and an essential oil screening and development framework is discussed.

Introduction

Essential oil production is a specialised agroindustry. Agricultural enterprises not directly involved in the flavour and fragrance industry undertake most of the world’s production. This infers a barrier to new essential oil development, as the main consumer of natural aromatic products is the flavour and fragrance industry. Natural product researchers and primary producers generally lack knowledge about the specific technical uses and applications of essential oils. The nature of the flavour and fragrance industry is not fully understood. This has in the past led to poor appreciation of the market and potential for new essential oils. Essential oil development in Australia is hindered by three other factors. First, new essential oil development is not only a new product development but it involves entry into a new industry as well. This increases the complexity of the product development process. Secondly, Australia is geographically remote from the major consuming markets of Europe, Japan and the United States. This increases the difficulty of gaining useful information about essential oil uses, applications and markets. Thirdly, the Australian market is less than 2% of the world market which prevents new essential oils being developed on the strength of the domestic market.

Characteristics and Trends of Worldwide Essential Oil Production

Essential oil production is scattered over many remote locations around the world. Much production is domestically consumed in producing countries and not reported in trade statistics. Climatic changes, diseases, variable yields, poor organisation, distance and language add to the problem of accurately estimating the value of world essential oil production. The author’s estimate of the total value of world production in 1994 was approximately US$ 750 million (Hunter 1994). Lawrence (1993) reported that 20 essential oils make up approximately 45 per cent of total production value. According to Buchel (1990), over 50 % of all essential oils produced are used in the flavour industry. The production of each essential oil must be considered a separate business because of the varied importance, different characteristics and uses of each material (Verlet 1993). Worldwide essential oil production patterns and practices are undergoing some transformation. Many traditional essential oil production regions, located in industrialised countries are becoming uncompetitive because of rising labour costs. Consequently, the production of some essential oils is being slowly relocated to new geographical regions, primarily in developing countries (Hunter 1995). Technology development is also beginning to have major impacts upon essential oil production. Improvements in mechanisation are necessary for existing industries in industrial countries to remain competitive. Production costs are being reduced through advances in tissue culture, cloning and other biotechnologies. Growing concern about residual traces of toxic substances in natural materials is bringing pressure on producers to organically cultivate essential oil crops. Likewise concern over solvent traces in natural materials, undesirable in both flavour and fragrance applications, is reflected in the wider use of alternative extraction methods, like CO2 extraction. These trends are increasing the barriers to industry entry due to higher capital and technology requirements (Hunter 1996).

The Characteristics and Classification of Essential Oils

Essential oils are considered commodities, but are by no means a homogeneous group of products. The essential oil trade has its own culture and business strategies. Unger (1987) summarised the peculiar characteristics of trade as follows:

a. flavour and fragrance ingredients are subject to derived demand; where demand originates from final

flavoured and fragranced end product demand,

b. demand for flavour and fragrance ingredients is relatively inelastic in the short term,

c. flavour and fragrance ingredients are subject to fluctuating and cyclic demand,

d. purchasing and use of flavour and fragrance ingredients is based on artistic and technical complexity, and

e. the world market is geographically concentrated

Although trade statistics indicate market size for many individual essential oils, this information is of limited use in evaluating new essential oil potential. To evaluate the commercial potential of new essential oils, a market orientation (i.e., potential uses, characteristics, strengths and weaknesses) is required, rather than a statistical

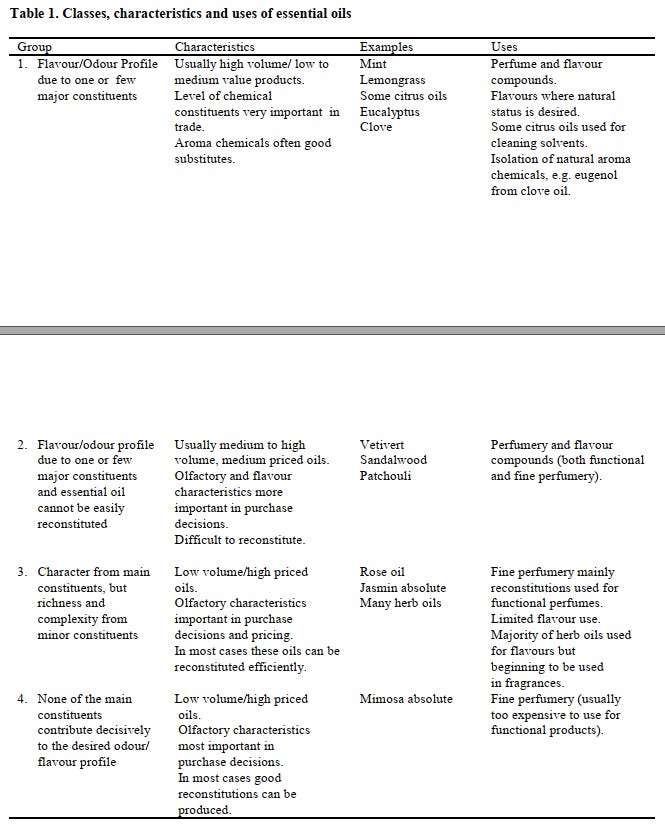

analysis of the essential oil trade. Some basic classification system is necessary to use as a tool for evaluating development potential and to indicate the types of business development strategies required. The basic classifications of essential oils (Naf 1989, Petrzilka and Ehret 1991) are combined into a single grid shown in Table 1.

Group 1: The olfactory profiles of essential oils in this group are dominated by a single or few major constituents. The production of many essential oils in this group relies on high capital investment and mechanisation as the key to competitive advantage. The mint industry in the United States is a good example of this (Borst 1988). Other essential oil crops in this group are produced by smallholders in developing countries. The smallholder production sector has only survived because; a) the cultivation of certain essential oils is not profitable in industrialised countries, b) full mechanisation is not possible and c) cultivation of some plant species is only possible for a few months each year (Verlet 1993). The citronella industry in Indonesia is a good example of this (Harris 1987). Prices for essential oils in this group are kept at relatively low levels due to the availability of substitutes (other essential oils and synthetic aroma chemicals) and competition between producers in developing countries.

Group 2: Most essential oils in this group are produced by smallholders in developing countries along the tropical latitudes. Some are produced on plantations with low cost labour supply as a source of competitive advantage. Currently, many developing countries are experiencing high rates of rural/urban transmigration, so low-cost labour as a source of competitive advantage is under threat (Anon. 1991). Fluctuations in prices occur when there is a mismatch of supply and demand on the world market. Generally, in times of supply shortages, higher prices will encourage existing producers to increase production and attract marginal smallholders back

into production. High prices and shortages of essential oils in this group may not necessarily indicate potential opportunities to develop these essential oils in new geographical locations, as existing producer countries can easily increase production levels (Robbins 1982). There are few cost-effective substitutes available to the

flavour and fragrance industry for essential oils in this group. The lack of close substitutes enables producers to gain slightly higher marginal returns for these oils compared to those in group 1 (Hunter 1992). However, substitutes for essential oils in this group may appear in the future through technology advancement.

Group 3: Essential oils in this group are primarily used in perfumery. These materials are valued for their depth, quality, complexity and richness in olfactory profile. Many of these materials are still traditionally cultivated (Konur and Robertet 1983). However as production costs are rising in developed countries, the production of these materials is being encouraged in developing countries (Anon 1993), often under sponsorship of major companies (McKay 1990). Generally, these materials are becoming too expensive to use in functional perfumery, where reconstitutions and specialties have mostly replaced them (Fenn 1988). Herbaceous oils are limited to

minor use in flavour compounds (Robbins and Greenhalgh 1979). Changing market trends have increased the use of some herbaceous oils in fragrance applications, but aggregate demand has not increased to any great extent.

Group 4: Essential oils in this group, like essential oils in group 3, are valued for their olfactory profile and are mainly traditionally produced. The availability of good reconstitutions for these essential oils has limited the use of these materials to fine perfumery applications.

Essential oils in groups 1 and 2 tend to be traded like pseudo-commodities, but strong product differentiation, based on chemical constituent levels still exists. Other industrial uses for many of these oils add to traded volumes. Essential oils in groups 3 and 4 are traded more like specialty and fine chemical products where quality plays a major role in price determination. Demand tends to be inelastic in the short term, as manufacturers are locked into using selected essential oils in the formulation of existing products. Past price trends and a poor supply history for some individual oils has encouraged the use of alternative materials in new products.

The above classification system can be used to generally identify essential oil use and trade characteristics. This establishes a structure from where further specific market analysis can be undertaken.

Evaluating the Characteristic Strengths and Weaknesses of New Essential Oils

The market potential of a new essential oil depends upon its potential uses and applications in the flavour and fragrance industry. The scope of potential uses and applications directly corresponds to the characteristic strengths and weaknesses of the essential oil. By objectively identifying the characteristic strengths and weaknesses, estimates of the oil’s perceived value to end users can be made. Kastner (1991) developed a set of criteria by which new perfumery materials can be examined. The list developed by Kastner primarily referred to synthetic materials and is modified below so the criterion is relevant to new essential oil evaluation:

The Novelty of a New Essential Oil

The major factor determining novelty is the perceived uniqueness of the new essential oil’s organoleptic profile. Thus, the degree of novelty is limited by the closeness of potential substitutes. The concept of novelty extends to essential oils that are cheaper sources of natural aroma chemicals. New natural sources of aroma chemicals would also fall into the category of novelty.

The Potential Uses and Applications of a New Essential Oil

Without perfumers and flavourists perceiving applications potential, a new essential oil will remain in the realm of curiosity. Time, effort and imagination on the part of perfumers and flavourists is required to discover useful applications for new essential oils. It is under this criteria that most new essential oils will struggle to find acceptance as a new aromatic material.

The Closeness of any Substitutes to a New Essential Oil

It is difficult to find essential oils that cannot be duplicated by reconstitution. New essential oils with close substitutes are of little value to the flavour and fragrance industry, unless they can offer a significant cost or stability advantage. The only exception is when a new essential oil is a source of a natural aroma material.

The Stability of a New Essential Oil

One of the major problems associated with essential oils is stability in end products. Many processed food products undergo harsh cooking procedures during manufacture. Cosmetic bases often contain free fatty acids, even after neutralisation. Essential oils that contain high levels of terpenes, tend to polymerise on exposure to light and air, discolour end products or are not stable in high alkaline or acidic media. Synthetic aroma chemicals and specialties are generally more stable than essential oils and are used more extensively in functional perfumery.

The Cost Price/Performance Ratio of a New Essential Oil

The cost price/performance ratio is important to the application potential of a new essential oil. If a new essential oil does not offer a perceptible odour/flavour at a low concentration, then its value to the flavour and fragrance industry is greatly diminished unless it is very cheap. Poor performance under this criteria will negate the potential of most new essential oils for application in functional perfumery. The

Toxicity of a New Essential Oil

The cost of proving a new material is safe to use in flavour and fragrance compounds is a major deterrent to the development of new aromatic materials. The industry has an impeccable reputation for self regulation. Most international flavour and fragrance houses would not consider using a new essential oil unless it meets IFRA safety and toxicity recommendations and is included on the FEMA GRAS list.

The General Consistency of Quality and Supply

Natural materials will vary in quality according to geographic origin, type of soil, level of nutrients in the soil, climate and weather, rainfall, time of harvest, season, methods of extraction, altitude and the incidence of pests and diseases. Likewise there are risks with continual supply of natural materials because of adverse weather conditions, changes in climate, floods and other natural disasters, wars, political upheavals and the inexperience of new producers. Launching new consumer products requires large investments on the part of end product manufacturers. Flavour and fragrance houses do not want to be placed into the position of being unable to supply a manufacturer with a perfume or flavour compound, because of the unavailability of a raw material.

The Prevailing Market/Product Trends

Market and product trends slowly evolve. Changes in market trends are the results of complex forces such as technology, advertising and cultural influence upon consumer tastes and preferences. A particular essential oil may become more or less important to the flavour and fragrance industry, depending upon these trends.

The Current Level of Technology

New technology advances influence the value of existing aromatic raw materials to the flavour and fragrance industry. The development of new essential oil reconstitutions are aimed at eliminating some of the potential toxicity problems of some essential oils. Reconstitutions are generally more stable and cheaper than their more expensive natural counterparts. As better and more cost effective reconstitutions are developed in the future, the use of some individual essential oils will decline. The major threat to the development of new essential oils is the

continued development of synthetic aroma chemicals. Since the advent of new analytical techniques like GC-MS headspace analysis, aroma chemical and specialty product manufacturers have been better able to isolate powerful aromatic molecules from essential oils and synthesis these compounds. The discovery of new aroma

chemicals in essential oils will more likely lead to synthesis rather than cultivation.

Opportunities for New Essential Oils

Now that a basic format for evaluating market potential has been outlined, opportunities for new essential oil development can be discussed. These opportunities fall under three broad categories.

The Introduction of Existing Commercial Essential Oil Crops to New Geographic Regions

Until recent times the introduction of existing commercial essential oil crops to new geographical regions would have been difficult to contemplate, except in exceptional circumstances such as major wars and decolonialisation. The conservative nature of the flavour and fragrance industry is now changing as the production costs of essential oils cultivated in industrial countries are increasing. The industry is now accepting products produced in nontraditional regions. However, it will be the developing countries that will be the main beneficiaries of opportunities in this category due to competitive advantages based on low labour costs. How well developing countries are able to exploit these opportunities will depend upon their individual abilities to overcome specific problems such as the lack of a research infrastructure (Kiew and Lajis 1994), political instability, the capacity to invest (Hunter 1993) and other structural problems (Nicola 1993).

The Reintroduction of an Essential Oil

The production of many essential oils has ceased for particular reasons over the years. However, in the last few years some essential oils have been reintroduced into commercial trade. Chempaka concrete (Michelia champaca) is once again on offer from China and Frangipanni absolute (Plumeria acutifolia) is on offer again from India. With greater interest and support from the flavour and fragrance industry, the production levels of these materials will increase (Malcolm 1994).

The Introduction of Novel New Essential Oils

The trend towards greater use of natural ingredients by the food industry is creating opportunities for the introduction of novel new essential oils. We may be encouraged by the flavour industry’s increasing demand for natural materials. A recent prediction suggested that essential oil sales will soon approach synthetic material sales in the USA (Gallagher 1993). There are also opportunities for essential oils that are cheaper sources of natural aroma chemicals. For example, the production of Lemongrass oil has greatly declined over the years because of the availability of cheaper substitutes like synthetic citral and Litsea cubeba oil.

The use of essential oils in fragrance compounds has declined in recent years and no longer has its place of dominance, especially in the lower cost functional compound market. Synthetic materials now make up about 86- 95 % of fragrance compounds (Fenn 1990). As the technical requirements for cosmetics, personal care and household products increase, the use of natural materials in fragrance compounds will become even more limited. It is unlikely that many new essential oils will meet the stringent criteria by which aroma materials are evaluated in the functional perfumery area. Nevertheless there is some limited potential for floral essential oils in fine perfumery. This is a small market and perfumery houses will have to be convinced that any new essential oil can be supplied on a consistent basis.

The Essential Oil Development Process

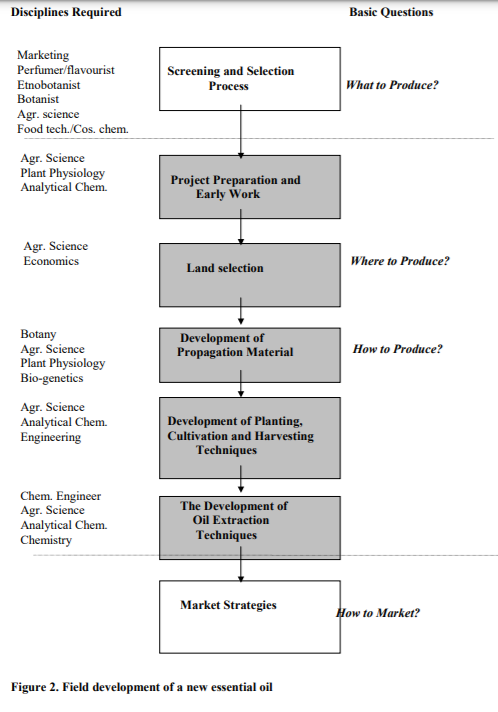

The task of developing a new essential oil for commercial production must be orientated towards answering four basic questions: what to produce, where to produce, how to produce and how to market.

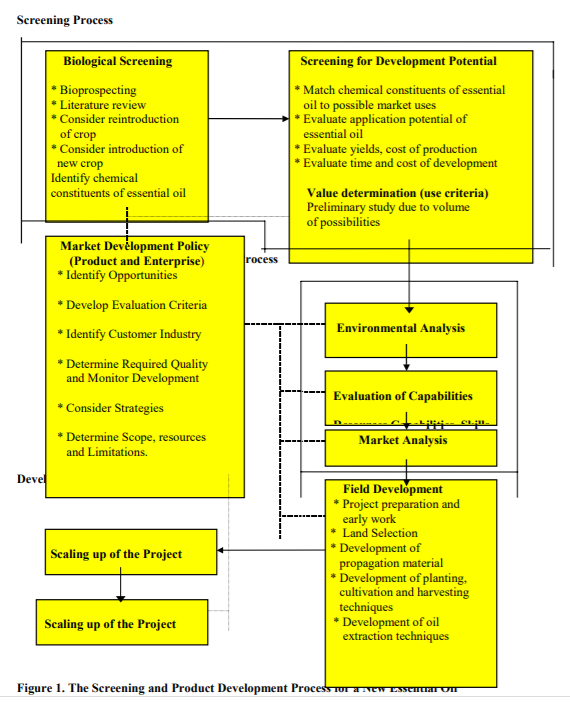

An essential oil development program (Figure 1) will first involve a plant screening and selection process. The rest of the project will be concerned with developing the most convenient set of strategies for propagation, cultivation, harvesting and processing the crop. During the project, equal attention must be given to market development.

Essential oil development is expensive, time consuming, resource demanding and can in many cases be quite rewardless. Before any research and development is undertaken, the scope and limits of the project must be defined through a policy statement. The main objective of the market development statement is to create clear development objectives for the project, identify the resources required and define limits on the costs. The market development policy statement requires careful consideration. The scope of this process can be appreciated from consideration of the following questions:

a) will indigenous flora be screened? (if so, plant biogentic development will most likely be required)

b) will there be consideration about introducing new crops from other geographical regions?

c) will all the various climates and micro climates throughout the country or state be considered, or will consideration be limited to a specific location?

d) what will be the timeframes of the screening process and who will fund it?

e) will other natural product potentials like traditional medicines, phyto pharmaceuticals, aromatherapy oils and cosmetic extracts be considered?

f) what form of production and marketing organisation will be employed should the crop be commercialised?

g) are there any underlying social, political or economic considerations to take account of ?

h) where will research and development expertise come from?

i) what levels of commitment can be expected from business, farmers, scientists and governments?, and,

j) if knowledge is generated from research, will it be used?

The Screening Process

After formulating the market development policy statement, the screening process can commence. Most research projects commence with some form of screening process, either formal or informal. The aim of this process is to develop a short list of probable crop candidates for closer evaluation. Only plants that have some realistic commercial potential should be included on the short list. This process involves simultaneous biological and development potential evaluation. Adequate time should be allocated for the screening process. Whether this process is restricted to desktop evaluation or involves some preliminary field work will depend upon available time and resources. Without a proper screening process there is risk that any future field research will be of an ad hoc nature which may result in an unmarketable product.

The screening process corresponds to the product ideation process used in industrial and consumer product development (Crawford 1983). The major difference between agroindustrial and industrial product development lies in the product conceptualisation process (the ideation process). The selection of an essential oil for product development requires a systematic elimination of potential possibilities through biological screening and development potential evaluation, rather than lateral idea conceptualisation used in industrial product conceptualisation.

The evaluation of essential oil market potential is only part of the total screening process. The screening process must also take into account the limits imposed by the physical environment (climate, rainfall, soil, sunlight hours, soil type, pH, water holding capacity, drainage, topography, etc.) and production economics. All these factors must be considered simultaneously. Lack of appreciation of the interdependence between production and market development has led to many failures by new producers (Green and Hone 1991).

The process of screening aromatic plants for development potential is complex due to the multiplicity of factors in both sets of considerations (biological screening and development potential evaluation). All factors must be found to be compatible. Given that over 50 possible aromatic plants may be screened for potential, some system of handling the information in a manageable manner must be devised. The more ordered and systematic the system to handle the compilation of such data, the easier and more efficient will be the process.

Environmental Analysis

The environmental analysis is a process where threats and opportunities for the short listed essential oil crops are more thoroughly evaluated. This process should be primarily concerned with the following strategic questions:

a) what are the difficulties and costs involved in developing the crop?

b) what will be the barriers to entry for other potential producers?

c) can the plant be developed into a feasible commercial crop with some form of competitive advantage over other potential producers (or producers of substitutes) in the future?

d) what are the capital outlays compared to that required to cultivate and process alternative crops?, and,

e) what are the returns compared to alternative crops?

Evaluation of Capabilities

By this time in the development process, there should be a fair idea of what is required to develop a selected plant into a commercial crop. The development of an essential oil as a commercial crop requires a multidisciplinary approach in dealing with most aspects of research and development. The disciplines of ethnobotany, botany, plant biology, biochemistry, chemistry, agricultural science, chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, analytical chemistry, flavour and fragrance technology, food technology, cosmetic science, marketing and finance all make a contribution and bear direct relevance to the commercial development of an essential oil.

Market Analysis

A full market analysis should be undertaken on the selected essential oil crop(s) before field development work commences. This process will deal with more specific questions about market potential:

a) have specific applications and uses for the new essential oil been identified?

b) does the new essential oil fulfil and satisfy a particular need?

c) are these specific applications and uses important?

d) what materials are currently used for these identified applications?

e) what would be the appropiate pricing of the product?

f) what production volumes would be required?, and

g) can customers be found for this product?

At this point in the project experts from the flavour and fragrance industry should be involved in the development process. This could involve collaboration and dialogue with end users. As the project progresses, the end user can comment and provide feedback on samples of the essential oil. An end user can provide valuable olfactory/organoleptic opinions, undertake some independent GC-MS analysis and even assist in applications development. This will also provide those involved in the project with some feedback and encouragement, something that is needed for continued motivation in long research and development programs.

The project analysis to date should have identified specific commercial aims that will become the reference point for all subsequent research and development. This will help to ensure that the product developed will meet identified expectations.

Essential Oil Field Development

A field development flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Project Preparation and Early Work

Thorough and systematic work by this stage may have assisted in developing some understanding of what factors influence the quality and yield of the essential oil crop. Efforts should be concentrated on examining only the factors that are believed to be the most important. Decisions can be made as to which broad disciplines will be the most important to carry out further inquiry. Early indications may suggest that initial work on basic plant processes, such as enzymatic processes, may be beneficial before agronomic work in the field is attempted, especially if the plant is not domesticated. Preliminary work studying the physiological processes of the plant may be beneficial and necessary to identifying important growth variables, before progressing to agronomic studies at the field level, where an open system is examined. This will also assist in developing research protocols to prove or disprove any conceptual hypothesis, based on the plant physiological data. A budget and time frame with predetermined milestones can be developed.

Correct botanical identification of the plant is fundamental to the project. An incorrect identification may lead to a long and expensive research process that yields no viable commercial result. Botanical information must include correct chemotype identification. A particular taxon of flora may have several different chemotypes, of which only one may be commercially useful. This is very important and is regularly overlooked by potential producers.

Land Selection

Commercial essential oil production is concerned with obtaining the maximum quality and quantity of oil per unit of land. Therefore land that provides the most favourable conditions should be selected to ensure the maximum probability of success. Land characteristics should, as much as possible, match plant requirements (if known). The local micro climate, the propensity of the land to flood and become waterlogged, access to irrigation water, roads and the previous use of land are also important considerations and should be carefully examined.

The Development of Propagation Material

The quality of propagation material has a major influence upon oil quality and yield and is an important determinant of the overall costs of production. Possible propagative methods are restricted by the species characteristics of the plant in question.

The most straightforward method of selecting propagation material is through cultivar screening and selection. A plant variety study may be necessary to evaluate different cultivars. Cultivar selection will assist in finding the best overall quality of breeding stock for the field experimentation. An index selection process may be necessary to screen plant specimens for the best desired characteristics (Slee 1992).

If an indigenous, undomesticated plant has been selected for development, some biogenetic development may be required to adapt it to field cultivation. Biotechnology disciplines can be employed to enhance genetic attributes in a relatively short period of time. Somaclonal variation can be used to develop new genetic varieties through in vitro culturing of the somatic cells of the plant. Plant cells can be regenerated through micro propagation and grown to maturity where a further selection process can be undertaken. The major difficulty with this method is in identifying the correct germplasms to manipulate at this early stage of plant knowledge (Evans 1986). Other methods such as mutagenesis can be used to develop superior strains containing essential oil (Naragund 1983).

Once the desired propagation material has been identified or developed, it is a matter of scaling up propagation, to provide enough material for field trials. The methods used to scale up will depend upon many factors, cost efficiency being of prime importance.

Development of Planting, Cultivation, Harvesting and Management Techniques

Field experimentation will confirm or disprove the conceptual hypothesis developed during the earlier stages of the project. The primary objective of field research is to determine the most efficient and economical practices that lead to the best quality and highest yield of oil.

Field trials are undertaken in an open environment where all variables play a role in the result. It is impossible to monitor and control all these variables at one time. Therefore only a small number of important and influential variables, such as plant density, nutrients and moisture can be chosen for manipulation and monitoring. Factorial and replicated experimentation are the most systematic and statistically reliable way to ensure data validity. Trade offs and compromises will be necessary when selecting which variables to manipulate and monitor, so trials remain manageable and generate useful information.

The timing of harvest has great influence on the quality of foliage harvested, and the volume and quality of oil recovered during extraction. Therefore, optimal harvesting times have to be determined. Practical experience supported by regular sampling, GLC analysis and biomass estimation will help to determine the best harvest times. The correct determination of harvesting time is critical for essential oil crops that develop their commercially valuable constituents through the biosynthesis of precursors. This biosynthesis will occur at a particular point in the maturity of the crop, under certain conditions. It is also necessary to determine what factors trigger this biotransformation.

The development of harvesting techniques will depend upon the ability to mechanise the harvesting process. This will require the design and modification of equipment to fulfil this specific role. The post harvest handling of foliage must also be given consideration, so efficient and high quality oil extraction can be achieved. Potential deterioration of the foliage and loss of oil through evaporation must be avoided. The cropping or mulching of foliage may promote enzymatic actions that may in turn change the chemical balance of the oil. Long delays between harvesting and extraction may lead to valuable oil evaporation or leaf fermentation. On the other hand, a long period of wilting may decrease the moisture content of the leaves through evaporation, thus allowing for a more efficient distillation.

The Development of Oil Extraction Methods

The composition of a natural aromatic material will be altered, modified or chemically changed during any extraction process. These may be only minor changes but can exert a marked effect on the odour of a natural aromatic material. Therefore any natural aromatic extract will never capture the same scent as it was in its original source. The objective of the extraction process, with a few notable exceptions, is to isolate the aromatic material from the source with minimal interference and modification of odour. This has an important influence on the selected method of extraction.

Developing the most effective method to extract an essential oil efficiently from a plant will require knowledge of the cellular structure of the plant and composition of the aromatic material within the plant. Applying this knowledge to perfect the optimal extraction processes for the plant concerned, will require repeated modifications to the extraction equipment and continual refining of the methods used.

Scaling Up the Project

Assuming everything looks promising from the field development work, the project should be scaled up to pilot commercialisation. It should already be established that the new crop is commercially viable, production economics are sound and any major production problems can be solved. Scaling up will be restricted by the amount of propagation material available, but two to five hectares should be enough. The pilot commercialisation stage provides opportunity to improve production techniques, confirm oil yield, quality and production costs. On the market development side, the oil produced at this stage can be used in initial marketing and selling. Once pilot commercialisation has been successful, the project can be scaled up to full commercialisation.

Market Strategies

The basic market strategies used to commercialise the crop will, to a certain degree, be dependent on the characteristics of the essential oil. The identified characteristic strengths and weaknesses of the new essential oil will highlight which product attributes are best to promote to end users. Market development strategies will, however, be strongly influenced by the scale of commercial production, the costs of production and the final quality of the essential oil. Where the enterprise will initially only produce small volumes, it may be necessary to identify small niche customers. Decisions must be made whether to sell to traders or directly to end users, to multiple buyers or to a single customer. Traders will be able to handle the selling of known essential oils, but may not be able to assist much in the marketing of a new essential oil that requires a lot of technical support.

One of the most important objectives of market development is encouraging potential users to evaluate the new essential oil. It would be an advantage to supply potential users comprehensive data and information that demonstrates the quality and novelty of a new essential oil. The provision of data should include the botanical source, geographic origin, constituents of the essential oil, appearance, odour characteristics, physical characteristics, qualities, tenacity, solubility, strengths, weaknesses, limitations, dilution rates, and recommended uses. To demonstrate the uniqueness of a new essential oil, one must understand in detail the potential applications of the material. Therefore, sample flavour and fragrance compound formulations should be developed to demonstrate the advantages of the new material. This would be invaluable in arousing interest from flavour and fragrance houses as one must remember that flavour and fragrance development is just as much an art as it is a science.

Conclusions

The organisations best equipped to develop new essential oils and exploit market opportunities will be those that take a multidisciplinary approach. Such an organisation must continually scan the market for opportunities rather than base its research focus on scientific curiosity. These organisations will form a nexus of government, research institution and business collaboration so that long term development strategies can be implemented. Government has an important role to play in this development. However due to the influence of economic rationalism and budgetary restraints, such long-term support will be difficult to obtain.

The traditional network of traders must be by-passed and direct dialogue with end users of essential oils sought, in order to gain the most useful market information. The commercial organisation must develop a strong extension capability that will involve the training, equipping and providing technical, managerial and even entrepreneurial guidance to farmers.

On a national scale, screening Australia’s biodiversity is the key to discovering new essential oils with novel characteristics. This is expensive and beyond the capabilities of any single organisation. The majority of natural product researchers are engaged in investigating other aspects of biodiversity. Perhaps screening for new essential oils is best approached in collaboration with other natural product screening programs.

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

References

Anon. 1993. A Different Perspective. DCI. Sept. p .60.

Anon. 1991. Ministry of Agriculture. The National Agricultural Policy (1992-2010). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 1.1.7.

Austin, J.E. 1966. Agroindustrial Project Analysis. The Economic Development Institute of the World Bank. (The John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore), pp. 22-24.

Borst, A.B. 1988. An Economic Analysis of the U.S. Mint Oil Subsector. Thesis, Michigan State University, Department of Agricultural Economics. pp. 45-47.

Buchel, J.1990. Flavouring with Essential Oils- Importance to Consumer and Producer. Proceedings of 11th. International Congress of Essential Oils, Fragrances and Flavours, Vol. 6., Commercial Papers, New Dehli. pp. 171-182.

Crawford, C.M. 1983. New Product Management. (Irwin: Illinois). Evans, D. 1986. Plant Biotechnology as a New way of Producing Essential Oils and Aromatic Chemicals. Proceedings of 10th. International Congress of Flavours, Fragrances and Essential Oils, New York.

Fenn, R.S. 1990. Aroma Chemicals - Past and Future. Proceedings of the 11th. International Congress of Essential Oils, Fragrances and flavours, Vol. 6., Commercial Papers, New Dehli, pp. 83-88.

Fenn, S. 1988. Aroma Chemical Useage Trends in Modern Perfumery. Proceedings of International Conference on Essential Oils, Flavours and Fragrances, Beijing.

Gallagher, M. 1993.The Natural Wave. Chemical Marketing Reporter. 12 July.

Green, C.L. and Hone, G.A. 1991. Essential Oil Production in Developing Countries. Proceedings of the 3rd. International Conference on Aromatic and Medicinal Plants, Nyons, France, 2-4 December 1991.

Harris, R. 1987. Tanaman Minyak Atsiri. (Penebar Swadaya: Jakarta). pp. 112-134.

Hunter, M.V. 1992. A Review of the Comparative Potentials of Some Essential Oil Crops in Peninsula Malaysia. Proceedings of 3rd. Malaysian International Conference on Essential Oils and Flavour Chemicals, Langkawi, Malaysia.

Hunter, M.V. 1993. The Feasibility of Developing an Essential Oil Industry in Malaysia and Possible Development Options. Proceedings of International Conference on Essential Oils, Flavours and Fragrances, Kuala Lumpur.

Hunter, M.V. 1994. The Need of a Multidisciplinary Approach to Develop Essential Oil Production in Malaysia. Proceedings of 8th. Asian Symposium on Medicinal Plants, Spices and Other Natural Products (ASOMPS), Melaka, Malaysia.

Hunter, M.V. 1995. Some Issues and Difficulties related to Developing New Essential Oils with Reference to the Essential Oil of Polygonum odoratum Grown in Southern Australia. Proceedings of the 13th.International Congress of Flavours, Fragrances and Essential Oils, Istanbul, Turkey. p. 404.

Hunter, M.V. 1996. The flavour and fragrance Industry: Structure and Future Trends, Cosmetics, Aerosols & Toiletries in Australia 9(6):29.

Kastner, D. 1991. A Fragrant Future. Manufacturing Chemist. March, p. 22 .

Kiew, R. and Lajis, N. 1994. Commercial Exploitation of Biodiversity. Proceedings of 8th. Asian Symposium on Medicinal Plants, Spices and Other Natural Products (ASOMPS), Melaka, Malaysia.

Konur, O.Z. and Robertet, P. 1983. The Agriculture and Distillation of Rosa Damascena in Turkey. Proceedings of 9th. International Congress of Flavours, Fragrances and Essential Oils. Singapore.

Lawrence, B.M. 1993. A Planning Scheme to Evaluate New Aromatic Plants for the Flavor and fragrance Industries. In ‘New Crops’ (Eds. J. Janick and J.E. Simon) (John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New York) p. 620.

Malcolm, C. 1994. In Search of Rare Essences for Green Minded Consumers. DCI. March, p. 24.

McKay, D. 1990. Oils From India. Manufacturing Chemist. July, p. 35.

Naf, F. 1989.From Essential Oils to Tailor-made Fragrance Chemicals in the Production of Perfumery Raw Materials. Proceedings of 11th. International Congress of Essential Oils, Fragrances and Flavours, New Delhi, India.

Naragund, V.R. 1983. Effects of Gamma Irradiation on Excised Leaves in Scented Geranium (Pelargonium graveolens, L. Heritt). Proceedings of 9th. International Congress of Flavours, Fragrances and Essential Oils, Singapore.

Nicola, M. 1993. Mini Dragons, (series on video), National Public Broadcasting System, USA.

Petrzilka, M. and Ehret, C. 1991. Natural Products. In: ‘Perfumes: Art, Science and Technology’ (Eds. P.M. Muller and D. Lamparsky) (Blackie Academic & Professional: Glasgow) pp. 499-531.

Robbins, S.R.J. 1982. Selected Markets for the Essential Oils of Patchouli and Vetiver. (Tropical Products Institute: London).

Robbins, S.R.J. and Greenhalgh., P. 1979. The Markets for Selected Herbaceous Essential Oils. (Tropical Products Institute: London). pp. 1-3.

Slee, M.U. 1992.The Basic Principles of Tree Breeding with Reference to Oil Breeding in Eucalyptus polybractea. Proceedings of Tea Tree Industry Forum, Wollongbar Research Institute, NSW, February 1992.

Unger, L. 1987. Basic Industry Trends in an Unstable Monetary and Highly Competitive Environment. Perfumer and Flavorist. 12(1).

Verlet, N. 1993. Essential Oils: Supply, Demand and Price Determination. Acta Horticultuea, 344:9-16.

Verlet, N. 1993. Commercial Aspects, In Volatile Oil Crops:Their Biology, Biochemistry and Production, (Eds. R.K.M. Hay and P.G. Waterman) (Longman Scientific and Technical: Essex) p.140.