Approval to demolish Shah Alam Stadium given under strange circumstances

Publicly unpopular project taking more twists and turns

The Shah Alam City Council (MBSA) has finally issued a demolition notice (Kelulusan Merancang) for the Shah Alam Stadium, after a delay of several months. Most strangely, the demolition notice has been issued without any appointment of a project developer, project consultant or building contractor. The notice issued on Christmas day, leaves many questions that need answers.

Clandestine Constitutional Crisis

According to a senior state government officer the local government order was given without any discussion within the State Assembly, executive council, or even the state legal advisor. Further, the senior state government officer said the Shah Alam City Mayor was under pressure from the palace to issue the demolition order.

Local adjoining communities are against the project, as well as many state civil servants. The state bureaucracy has been very slow to progress this project, thus hindering the finalization of the project. Word around Shah Alam is even the chief minister Amirudin Shari is hesitant over the demolition. It was reported in Bulletin TV3 that the chief minister was not his personal wish.

(English translation: It follows that the development is not his personal wish but rather the wish of the Sultan of Selangor, Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah; Raja Muda Selangor, Tengku Amir Shah and Selangor football supporters.)

According to reports, TNB has not yet removed transformer installations from the site.

The whole stadium area has been designated a restricted area to prevent community protests.

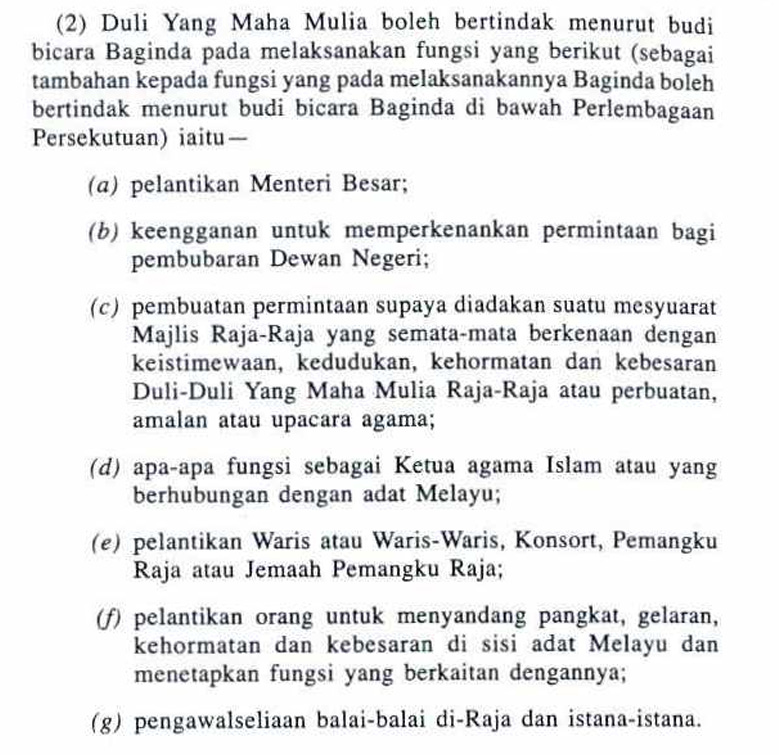

The issuance of the demolition notice brings Section 55(2) of the Selangor Constitution into question. Section 55 clearly states that the Sultan must act on the advice of the executive council or a member who is acting under authority of the executive council, in exercising his function under the Constitution.

Thus, the issuance of the demolition order may in fact be unconstitutional. The state legal advisor must give an opinion on this matter.

Shah Alam Stadium Developer not yet selected

MRCB was previously announced as the strategic partner of the Shah Alam Stadium project. The company has already invested in some of the preliminary aspects of the project – planning and design. However, MRCB has only received a letter of intent from the Selangor State Government.

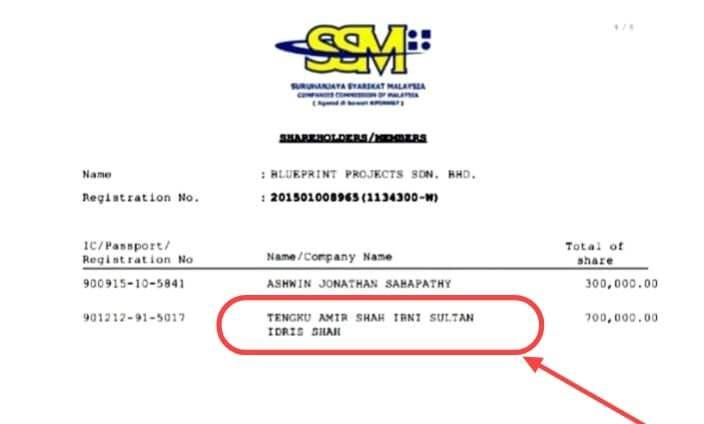

There is talk of another company, Blueprint Projects Sdn Bhd taking up some form of role in the project. The Companies Commission of Malaysia (SSM) registration shows that Blueprint Projects nature of business includes engineering contracting, building and investment property construction and consultancy. However, the company only has a paid-up capital of RM 1.0 million. This company is 70% owned by Tengku Amir Shah Ibni Sultan Idris Shah, the Raja Muda of Selangor.

Currently in Shah Alam there is great speculation as to why MRCB has not yet been officially appointed as the project contractor, and what (if any) will be the role of Blueprint Projects Sdn Bhd?

Why would the stadium be demolished if there is no contractor appointed?

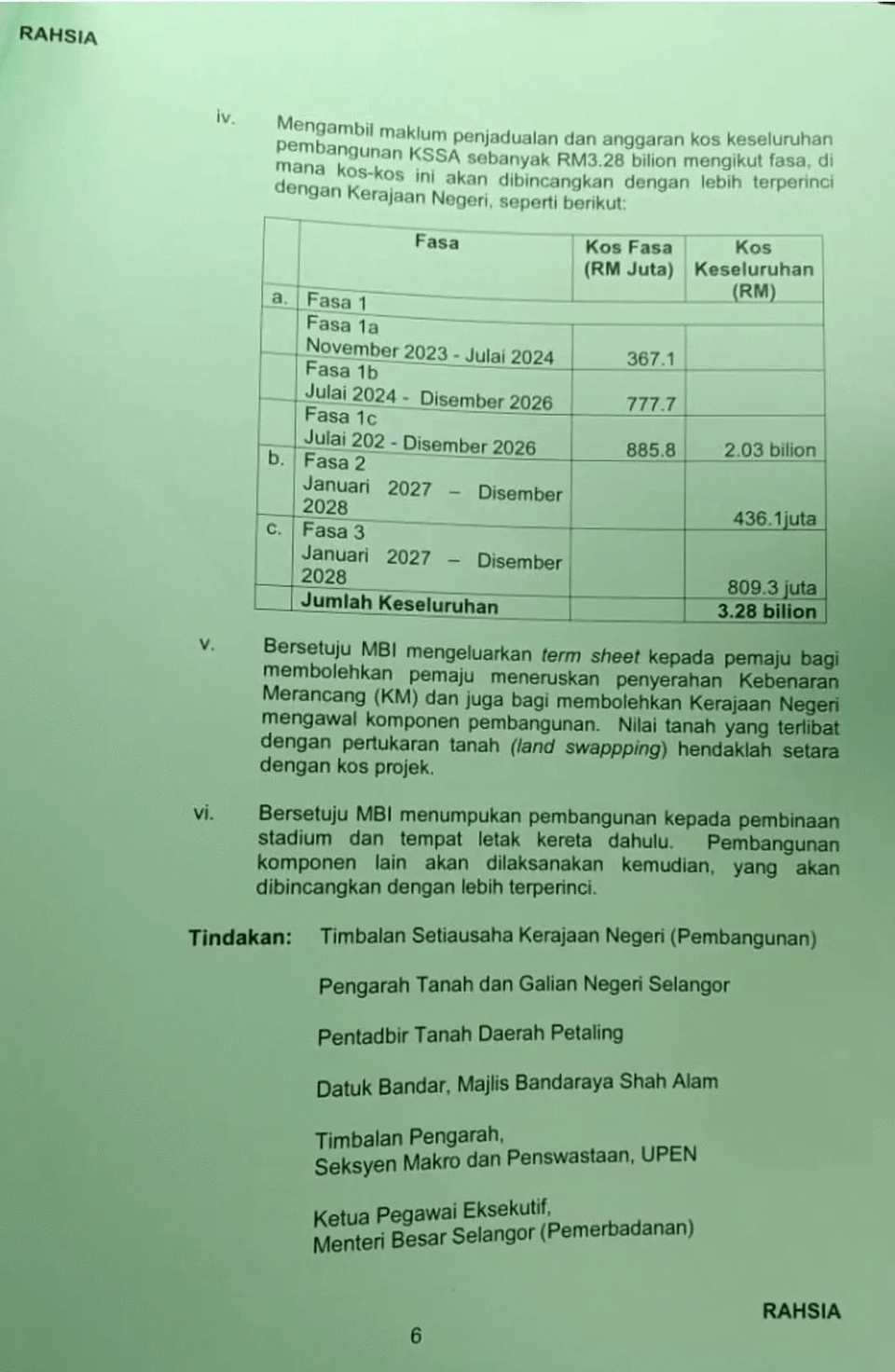

This is a real mystery. Why would the Shah Alam City Council issue a demolition certificate for the Shah Alam Stadium without there being any appointed contractors? Rumour has it that there is not any complete agreement about which prime pieces of land the Selangor State Government should hand over to the contractor for the RM3.28 billion project.

Most importantly, why is there no public tender process for such a massive project in Selangor? This appears an exorbitant price to pay for such a project.

Should there by a massive Shah Alam Stadium site in the first place?

The original estimate to refurbish the Shah Alam Stadium was estimated by the Jabatan Kerja Raya (JKR), or Public Works Department, to cost around RM 154 million. The tender papers sent out for the project specially specified a refurbishment. The cost of repairing the roof alone is only RM 10 million according to one of the original companies tendering for the refurbishment project.

Then it was announced in the media, with total surprise to the tenderers, that there would be a complete redevelopment of the Shah Alam Stadium Complex, adding in a shopping and commercial complex costing around RM 787 million.

Project papers approved by the State Executive Council actually approved the Shah Alam Stadium redevelopment at RM 3.28 billion. This is a staggering difference from an RM154 million refurbishment, and RM 787 million redevelopment.

So the repair costs to the roof of the stadium blow out from RM 10 million to RM 3,28 billion. The Selangor citizens are being taken on a massive ride. The capacity of the new stadium will only be a little over have of the existing stadium. Certainly not large enough to play a backup role to Stadium Bukit Jalil. If an event cannot be held at Bukit Jalil, Shah Alam Stadium is the alternative.

The Shah Alam Stadium has a sister stadium

The estimated life expectancy of the Shah Alam stadium is between 100-130 years. The Shah Alam Stadium was modeled on the Stadion Poljud in Croatia. This stadium was built in 1979 and refurbished before the 2010 IAAF Continental Cup Athletics, where the capacity was increased from 55,000 to 62,000.

Stadion Poljud in Croatia

The Shah Alam Stadium was built in 1990 and still has a potential long-life expectancy ahead of it. Why is the Selangor government even contemplating the demolition of the Shah Alam Stadium.

The question is why is the true cost of this project subject to the Official Secrets Act (OSA)?

It’s not too late to delay the project and undertake a transparent study, when RM 3.28 billion of state (public land) is at stake.

Subscribe Below:

We need a stadium mainly for the noble Malaysian politicians' sport of hanky panky.

And even when our dumb politicians, sports stars, sports fans, and the public can only "catch no ball".

As Professor Harding noted in his analysis of the Malaysian Constitution, there is no guide as to what principles judges are to rely on when interpreting the constitution. Principles of constitutional interpretation are not codified or even stated in the constitution itself. No Malaysian writer to date has even bothered to research this point inspite of the numerous flaws in constitutional interpretation by Malaysian judges and academics alike.

Judges and academics, lawyers and politicians alike in Malaysia have always treated articles of the constitution as if they were ordinary pieces of legislation like the crimes act, the family law act or the property law act. They are not. Hence the embarrassment and the blind attempts at searching for a solution whenever the constitution is at the heart of a dispute.

Take the Lina Joy case. It was treated largely as an issue of judicial review of an administrative action rather than one of religious freedoms. In Titular Roman Catholic Archbishop of Kuala Lumpur the relevance of considerations in administrative decision making was treated as equally important with constitutional freedom of expression.

The constitution must be interpreted within its own four walls. Although authorities from other jurisdictions may interpret similar or identical provisions and offer some guidance, they cannot be regarded as anything more than persuasive.

The constitution must be interpreted broadly. It is not statute where narrow interpretations may be justified. Without going further on the constitution in this matter we turn to the issue of the relevant apparently offending article as follows:

"Section 55 clearly states that the Sultan must act on the advice of the executive council or a member who is acting under authority of the executive council, in exercising his function under the Constitution".

It says nothing as to how the Sultan must act. It says nothing about what is presumed here that the Sultan in acting on the advice of the executive council or a member......"must do as he advises the Sultan" to do or refrain from doing.

The Sultan must accept their advise and act. But refraining from an action is also formally a step or an action. By using his own discretion which the Sultan also possess, and acting in a manner which departs from the actual or specific advise of the legislature or executive council, the Sultan is also acting on the advise. This is because the Sultan is allowed to exercise his own discretion in interpreting that advise.

By defying the advise of the Executive Council and or the legislature the Sultan is also taking a step or acting within his powers under the constitution.

There is nothing that the Executive Council or any part of the legislature can do to the Sultan if the Sultan fails to accede to their "advice".

There is authority within the commonwealth that supports the proposition that the sovereign may do as he pleases. But convention demands they act in conformity with the advise of the legislature, Executive Council (parliament) to preserve the harmony of the comity of the 3 arms of government to preserve unity of government.

There is no provision to effectively sanction the Sultan if he departs from the advise given him by the Executive Council / parliament.

The Sultan may dismiss the Executive Council as it has been done in the Commonwealth previously and there is ample precedent for the Sovereign to dismiss "his" government in the event of a conflict between the two.

Concluding, there is nothing sinister about the award of the contract to demolish the Selangor stadium, not any more than the Sultan of Johor granting the family of Robert Kuok the sugar and flour monopolies in Johore later spreading throughout the federation. There are many more such examples.