Cognitive Traps: Heuristics, Bias, Misconceptions, Fallacies and Abstract Inferences

Their role in entrepreneurial thinking

To handle the enormous amounts of incoming information and perform the decisions that have to be made requires some form of mechanisms that can ‘short-cut’ the interpretive and decision processes (Finucane et.al 2000). Heuristics and biases are a means to achieving this and as a consequence have an influence on our perception and reasoning. Heuristics assist decision making under uncertainty because of insufficient information from the environment. Heuristics and other biases compensate and thus assist people in seeing potential opportunities that others don’t (Gaglio & Katz 2001). They also influence how strategies are developed (Busenitz & Barney 1997, Mitchell et al. 2002, Alvarez & Busenitz 2001).

Heuristics are ‘short-cuts’, ‘rules of thumb’, decision rules or templates that aid quick judgments and decisions. Heuristics become embedded within our belief system. They can also be influenced by our deep motivations and reflect our social conditioning. Heuristics and other biases become intertwined within our knowledge structures and become a factor of influence in the assessments, judgments and decisions we make involving opportunity evaluation (Mitchell et al. 2004). They are part of the decision making process (Wright et. al. 2000). In effect heuristics are our programmed system of ‘common sense’.

Heuristics have the potential to assist the decision making process by cutting down on the person’s information load (Gowda 1999). They allow a person to make quick decisions about opportunities without undertaking formal analysis which would tend to highlight problems, thus preventing its exploitation[1]. Heuristics are important when windows of opportunity are very short (Tversky & Kahneman 1974). They also help in making quick strategy choices, saving time and adding to flexibility. Heuristics make up for lack of experience (Alveraz & Busenitz 2001) and drive intuition, which is independent of inputs from the cognitive perception process (Gowda 1999). This will trigger off the creativity process by imposing an alternative reality to what is perceived through the senses.

On the negative side, heuristics can become cognitive biases. Cognitive biases are errors of judgment based on misconceptions of the facts, memory errors, probability errors, motivational factors, and/or social influences. These are the basis of irrational reasoning which can lead to all sorts of mistakes in judgment (Baron 1998). The general conditions that people work under, particularly if it an entrepreneurial environment will normally be characterized with information overload, uncertainty, strong emotions, time pressure, fatigue and the need to do unfamiliar things with little prior experience. This type of situation is a stressful one and a potential trigger for distortion in perception and reasoning. This usually occurs without a person’s conscious knowledge of the fact (Wilson et. al. 1996). Human reliance on heuristics and biases tends to increase in busy environments described above (Gilbert, et. al. 1988), especially when immediate answers are required (Gilbert & Osborne 1989). This is where lots of irrelevant information works its way into the reasoning process (Chapman & Johnson 2003) and leads to cognitive biases that contribute to irrational and less than optimal decisions.

Heuristics and cognitive biases are believed to be caused by the process of attribute substitution. Attribute substitution occurs when a person has to make a judgment (of an attribute target) that is very complex. As a consequence of the complexity, the mind substitutes a more easily calculated heuristic attribute to simplify complexity (Kahneman & Frederick 2002). This occurs when the target attribute is relatively unavailable through reasoning (answer cannot be easily retrieved through memory), so an associate attribute (heuristic) is substituted. This process occurs because the heuristic is easily available in memory (i.e., a neural perception or primed in memory[2]) and this process is not detectable through the person’s reflective system. The attribute substitution process combines available knowledge and experience into heuristics that drive a new idea forward.

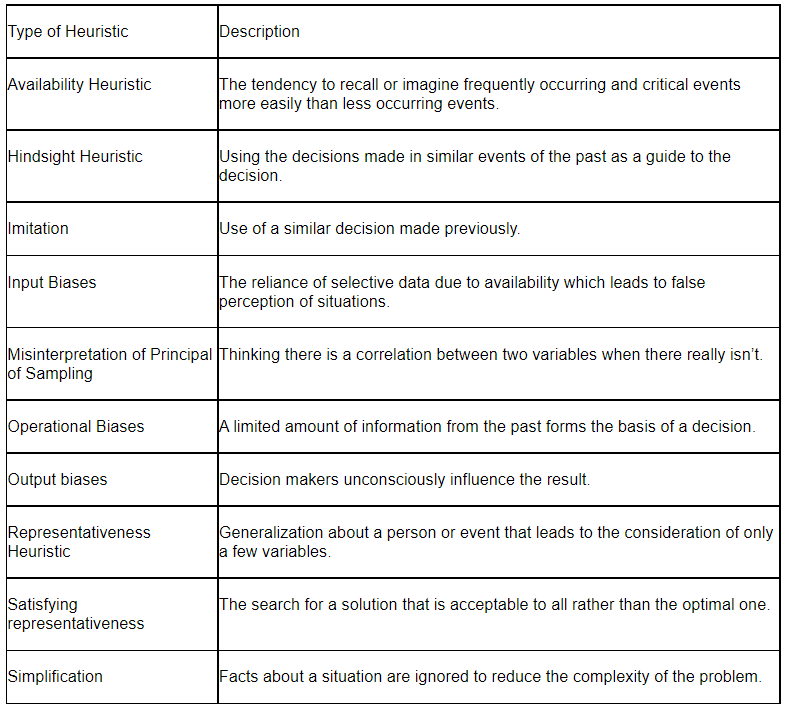

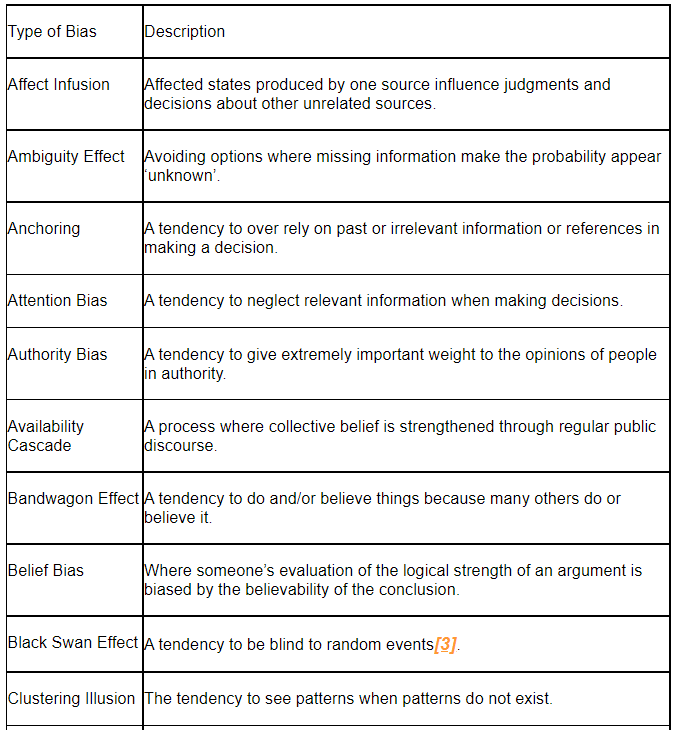

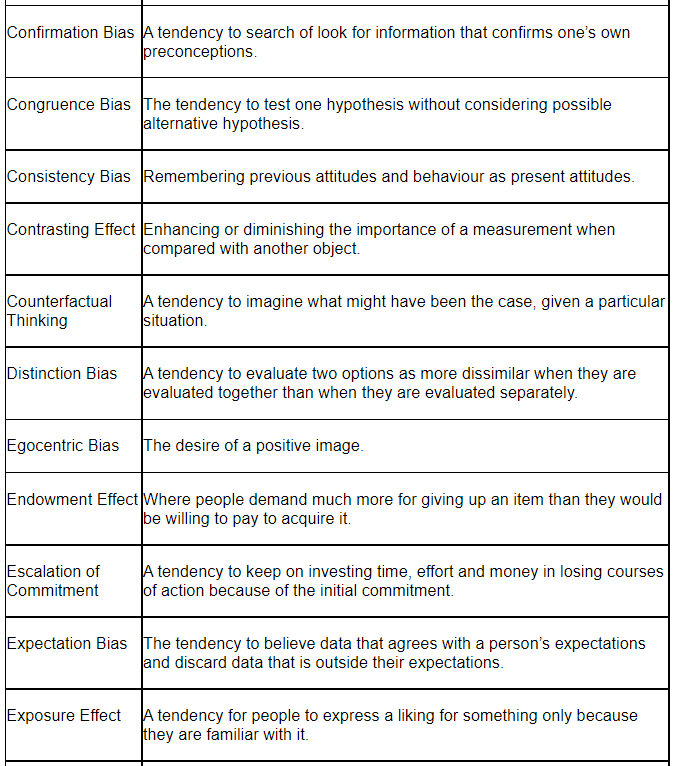

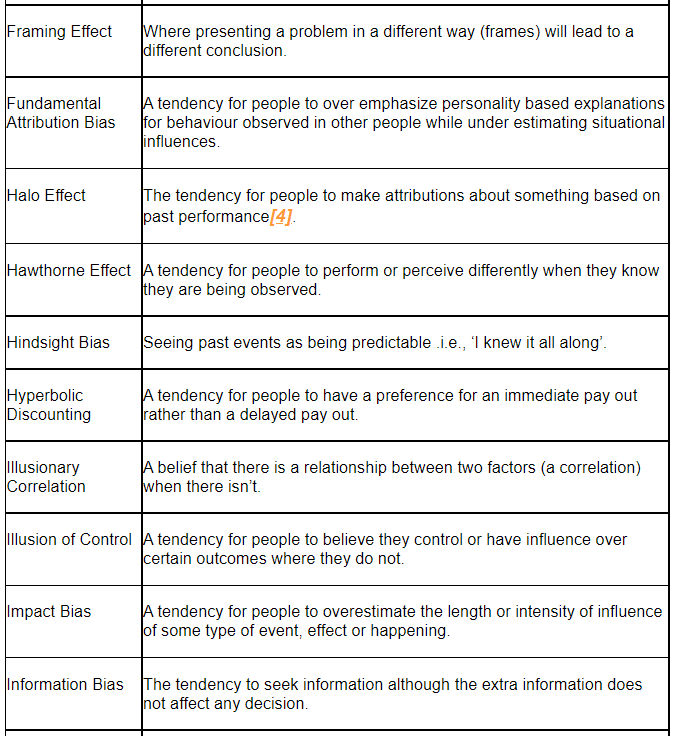

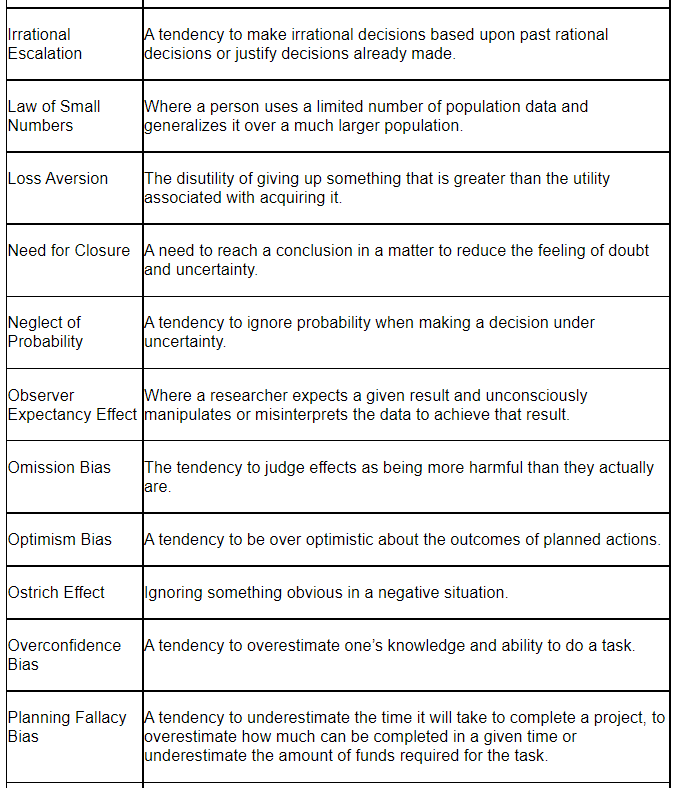

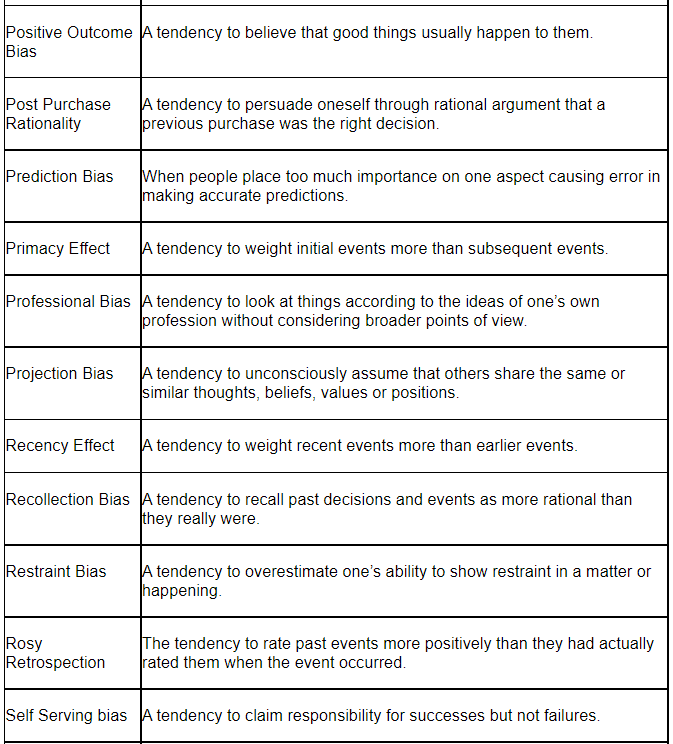

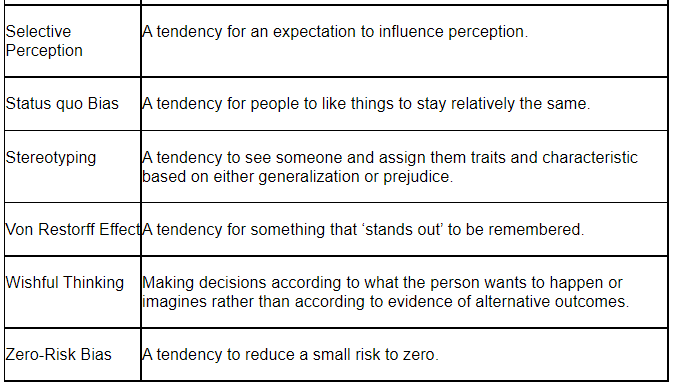

It is very difficult to detect heuristics and biases. However they can sometimes be picked up in narrative, as phrases like ‘I think’, ‘I feel’, ‘I believe’, ‘I reckon’ or ‘it is unlikely that’, etc. It is also very difficult to split heuristics from cognitive biases. In pragmatic terms, heuristics and cognitive biases are built upon a person’s belief system. However the cognitive bias is tended to be founded on misconceptions. Table 1. is a list of some heuristics and Table 2. is a list of common cognitive biases.

Table 1. A List of Some Heuristics.

Table 2. A List of Common Cognitive Biases.

Heuristics and biases have developed through evolution and learning. Our everyday experience continually reinforces them. In healthy situations heuristics will slowly change over time as experience confirms or disproves their validity and application to life situations. This slowly evolves our mental map so it remains relevant with the demands of the environment, so that we perceive things differently over time[5]. Peter Drucker (1994) calls vision the ultimate heuristic, our theory of how we do business. Therefore to survive in times of rapid change, our vision must also continually change.

Misconceptions

Misconceptions are false, flawed or mistaken views, opinions or attitudes. Errors and misconceptions are more likely to occur when knowledge about a specific area is inadequate and supports only partial understanding. Generalizations are needed to develop any understanding of a situation or event. This develops misconceptions which are taken as fact and used to grapple with new situations (Nesher 1987, Resnick et. al. 1989).

Misconceptions are wide through the community and form the basis of many heuristics and biases. They are particularly evident in the media. Tversky and Kahneman (1982) found that even professionals widely used the representativeness heuristic and law of small numbers in their work. Misconceptions can be strongly held and resistant to change (Clement 1987). Therefore misconceptions can retard and prejudice learning as new information coming in will tend to be rearranged to support existing misconceptions.

Fallacies

A normal argument consists of one or more premises and a conclusion. An argument can be either deductive where the premises provide complete support for the conclusion or inductive where the premises provide some degree of support for the conclusion. The stronger the premises, the stronger will be the case of the argument. A good deductive argument is therefore forms a valid argument. A good inductive argument is known as a strong inductive argument. A fallacy is an error in the premise or reasoning of the argument. It is not a factual error as the premises may be correct with the conclusion in error. A deductive fallacy is a deductive argument that is invalid. Fallacies therefore have poor premises, poor support for their conclusions, use irrelevant data, or analogies or make claims that are too wide and sweeping for their related premises.

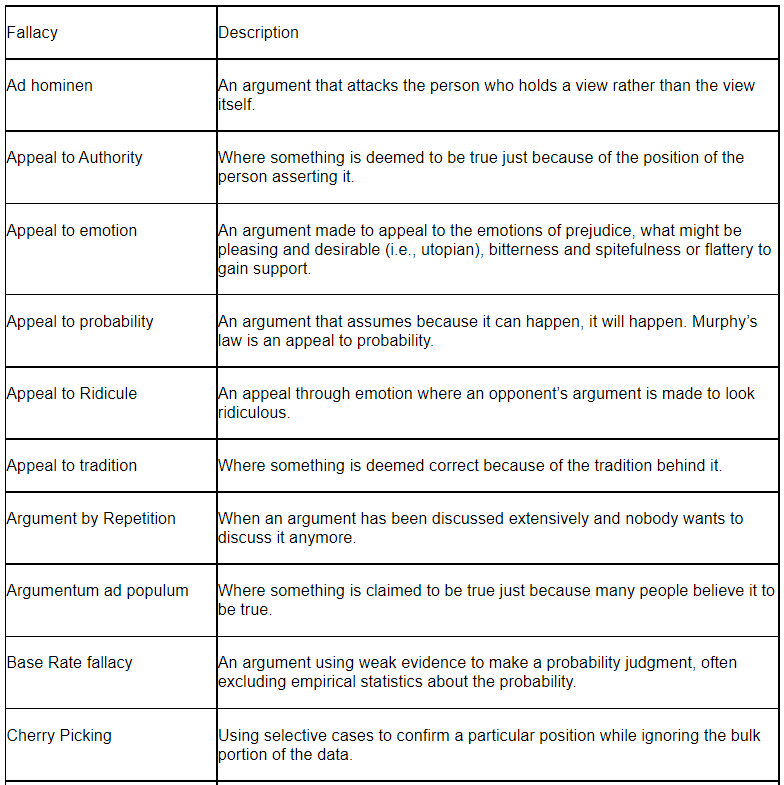

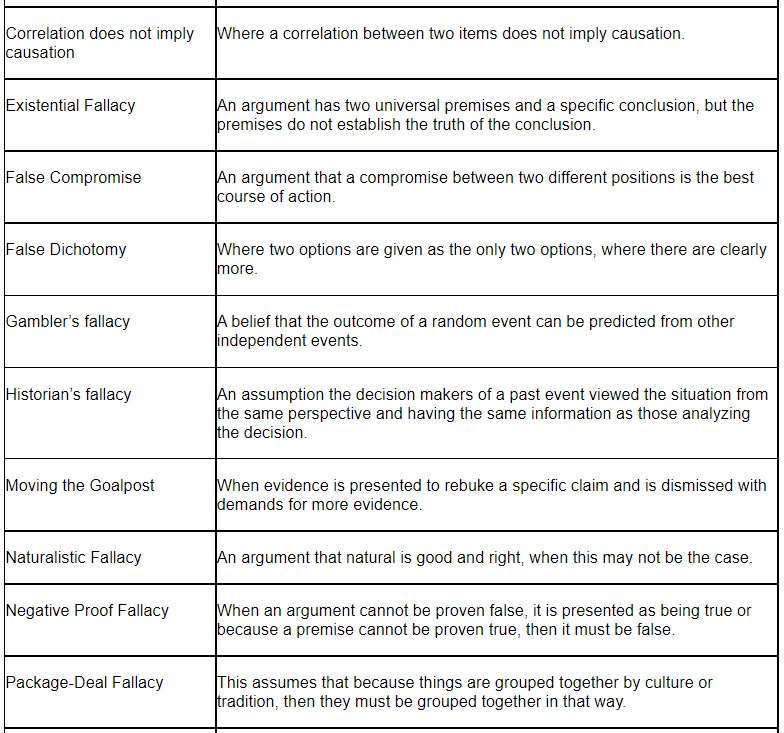

Fallacies are very common in the way we think, reason, and argue cases to both ourselves and others. Fallacies are particularly common when one is very passionate about something. Fallacies can be very persuasive and difficult to detect unless one is continually alert. They are very common in newspapers and the media. Some common types of fallacies are listed in Table 3. below.

Table 3. Some Common Types of Fallacies.

Abstract Inferences

Due to our minds being saturated with information, it is impossible to remember detail. To cope with this volume of information our mind develops abstractions or generalizations, simplifying the massive information we have to deal with. Therefore throughout everyday situations inferences are made from specific things we see to help us make quick assessments and decisions. We are usually unaware of the generalizations and inferences we make.

Abstract inferences help us to unconsciously develop emotions for people, things and events. These emotions trigger thoughts that influence the quick decisions we make about these situations. For example, if we were a salesperson we probably wouldn’t wait extra time for a store owner to return if we believe that ‘he never orders anything anyway’. Likewise we won’t undertake extra study for an exam where we believe that ‘I’m not good at this subject anyway’. We regularly make generalizations that we rarely question. These abstractions become a type of schema that influences our decisions and behavior. This is the process that leads to stereotyping.

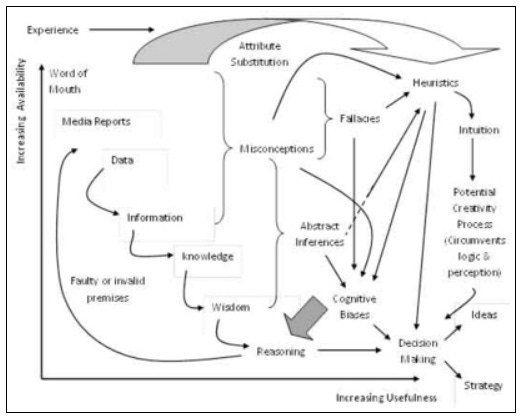

Figure 1. Informational and Cognitive Influences upon Decision Making.

Figure 1. summarizes our discussion on cognitive traps. The diagram shows the various informational and cognitive mechanisms that influence decision making. When humans face repetitive or similar decision making circumstances there is a tendency for heuristics to develop through attribute substitution. However heuristics are also influenced by misconception, fallacy and abstract inferences. Where these forces are overbearing on perception, cognitive biases will develop which that distort the reasoning process. Reasoning affects both the decision making process and the construction of fallacies and misconceptions as well. When reasoning is affected by biases, the decision making phase may produce less than optimal decisions. On the positive side, heuristics can block perception, replacing it with intuition which can trigger the creative process. The vertical axis shows the volumes of types of information available and the horizontal axis shows the increasing usefulness of information for decision making purposes.

********************************************************************

Originally published in Ovi Magazine 7th January 2013

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

Notes

[1] This is one area where entrepreneurial thinking may be very different from management thinking. An entrepreneur without perfect information will act on intuition and hunch. Any analysis will be mental rather than through the formal processes which managers in a company situation will tend to follow. Management analysis of new ideas will tend to frame the question; what is wrong with this idea?, why should it not be exploited?, what will be the potential problems?, etc. Thus analysis can become a very negative paradigm in management preventing new ideas emerging into new strategies.

[2] Priming occurs when an earlier stimulus influences a response to a later stimulus. For example, a person watches a television program the night before on conservation of forests. The next day someone asks the person for their views on conservation. It is likely that the person will give views and ideas that originated from the program on conservation the night before. This is assuming the person does not already have any strong views on the subject.

[3] See Nassim Nicholas Talab (2007), The Black Swan, New York, Random House Inc.

[4] See: Phil Rosenzweig (2007), The Halo Effect, London, Pocket Books, pp. 51-64.

[5] A mental map is a mental model made up of our schema, perceptions of things, people and events, our feelings and personal points of view.

References

Alvarez, S. A, and Busenitz, L. W, (2001). The Entrepreneurship of resource based theory, Journal of Management, Vol. 27, pp. 755-775.

Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: why and when entrepreneurs think differently than other people, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 275-294.

Busenitz, L. W, and Barney, J. B, (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 12, pp. 9-30.

Chapman, G. B, and Johnson, E. J, (2003). Incorporating the Irrelevant: Anchors in Judgments of Belief and Value, In: Gilovich, T, Griffin, D, and Kahneman, D, (Eds.), Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.

Clement, J. (1987). The use of analogies and anchoring intuitions to remediate misconceptions in mechanics, Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of AERA, Washington, DC.

Drucker, P. (1994). Post-Capitalist Society, New York, HarperCollins Publishers.

Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., and Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 13, No. 1., pp. 1-17.

Gaglio, C. M, Katz, T. A. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: entrepreneurial alertness, Small Business Economics, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 95-111.

Gilbert, D. T., Pelham, B. W., and Krull, D. S., (1988), On cognitive busyness: When person perceivers meet persons perceived, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 54, pp. 733-740.

Gilbert, D. T. and Osborne, R. E. (1989). Thinking Backward: Some curable and incurable consequences of cognitive busyness, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 57, pp. 940-949.

Gowda, M. V. R., (1999). Heuristics, biases and the regulation of risk, Policy Science, Vol. 32, pp. 59-78.

Kahneman, D. and Frederick, S. (2002). Represetativeness Revisited: Attribute Substitution in Intuitive Judgment, In: Gilovich, T, Griffin, D., Kahneman, D., Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgment, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University press, pp. 49-81.

Mitchell, R. K, Smith, J. B, Morse, E. A, Seawright, H. W, Perero, A. M, and Mckenzie, B, (2002). Are entrepreneurial cognitions universal? Assessing entrepreneurial cognition across cultures, Entrepreneurial Theory and Practice, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 9-32.

Mitchell, R. K, Busenitz, L, Lant, J, McDougall, P. P, Morse, E. A, and Smith, B. (2004). The distinctive and inclusive domain of entrepreneurial cognition research, Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, Vol. 28, No. 6, pp. 505-518.

Nesher, P. (1987). Towards and instructional theory: The role of students’ misconceptions, For Learning of Mathematics, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 33-40.

Resnick, L. B., Nesher, P., Leonard, F., Magone, M., Omanson, S. and Peled, I. (1989). Conceptual basis of arithmetic errors: The case of decimal fractions, Journal of Research in Mathematics Education, Vol. 20, pp. 8-27.

Rosenzweig, P. (2007), The Halo Effect, London, Pocket Books.

Taleb, N. N., (2007). The Black Swan, New York, Random House Inc.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Science, Vol. 185, pp. 251-284.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1982). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, In: Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., and Tversky, A., (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp. 3-20.

Wilson, T. D., Houston, C., Etling, K. M. and Brekke, N., (1996). A new look at anchoring effects: Basic anchoring and its antecedents, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol. 4, pp. 387-402.

Wright, M., Hoskisson, R. E., Busenitiz, L. W. and Dial, J. (2000). Entrepreneurial Growth through Privatization: The Upside of Management Buyouts, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 591-601.