Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management (2013), 1 (2), 7-51

Introduction

Creativity is an extremely important aspect of opportunity, strategy and entrepreneurship. Without creativity, very little would develop, function and contribute to the wellbeing of the enterprise. Creativity is especially important in;

· Generating new ideas,

· Developing sources of opportunities from new technological developments, competencies, resources and networks, etc.

· Combining resources, skills, competencies, networks, and strategies to create new ventures,

· Developing ideas along a vision and path of implementation (strategy),

· Managing competitive strategy,

· Developing flexibility within an enterprise,

· Managing growth, and

· Solving routine and non-routine enterprise problems.

The concept of creativity is elusive, cannot be observed directly, measured or even acknowledged until sometime after the creative act has taken place[1]. Relatively little research has been undertaken on creativity until the 1960s (Sternberg and Lubart 1996). However within the last three decades there has been a massive serge in research, new theories and the development of many creative tools.

Many creative ideas, products or processes are the result of a lifetime of work for any individual. Some may be extraordinary and rare like a painted masterpiece or theory about the cosmos. Some creations may answer perplexing questions and have far reaching influences, beyond the expectations of their creators. Consequently people assume that the way these creations come and the people that create them must in some ways also be extraordinary about the intellectual and cognitive capacities they possess. However the intellect required for creativity is not outside the norm and everybody is capable of exercising the same cognitive processes. Our thought processes are ordinary and utilize past knowledge with new information (Weisberg 1993). Within the process of creativity, there are no leaps or illuminations that come from nowhere. The Wright Brothers’ invention of the airplane, Thomas Edison’s invention of the light globe and Picasso’s development of a new style of painting were all the result of incremental advances built upon previous work. Creativity is not mysterious and can mostly be explained by computational concepts in artificial intelligence (Boden 1990).

Probably the greatest difference between highly creative and average people is that highly creative people are experts in their domain. They are also highly motivated which takes them along various paths of inquiry into matters of interest that others ignore. Highly creative people take intellectual risks and have immense perseverance that others don’t have (Sternberg and Lobart 1996). Complete immersion into a subject could be an important factor in gaining creative insights, especially in fields where there is an abundance of prior knowledge and experience (Proctor 1999).

It is creativity that allows us to see things differently and this is one of the main reasons behind our continued evolution. Creativity is a natural activity and probably depends upon our ability to be imaginative, open minded, curious, intuitive, insightful and able to tolerate ambiguity (Piirto 1998). The creative person needs to be flexible to react effectively to technological, economic, social and regulatory changes, under new circumstances, where new opportunity exists.

Creativity is an ever developing ability rather than a static attribute that someone is endowed with at birth (Simonton 2000). Creativity is not the result of a comfortable environment, but rather the broad life experiences a person has lived through which can enable a person to take fresh perspectives. The ability to be creative is probably enhanced more from the experiences of challenging life experiences than a stable and secure life, which may help develop the quality of perseverance (Simonton 1994). Perseverance is vital to creativity and problem solving, which is usually associated with barriers, obstacles and difficulties before the problem can be solved.

Creativity can be viewed as a process where the cognitive system utilizes attention to draw upon relevant knowledge, restructure problem information and look for analogies, new connections or associations within prior knowledge to solve a problem (Smith 2003, Smith et. al. 1994). Creativity can also be viewed as a product or outcome, where the result is recognized as being creative by others. The creative end may be a new product, new process, a piece of art, a new business model or a new strategy.

There is lack of consensus about what constitutes creativity and whether emphasis should be placed on the process, or the ends, and whether it is an individual or group phenomenon. From the point of view of this book creativity is generally defined as the production of novel, useful ideas or the production of solutions to problems. Creativity thus refers to both, the generation of new ideas, problem solving, as well as the actual idea or solution (Amabile 1983, Sternberg 1988, Weisberg 1988). Creativity is also about firm innovation, which is closely related to creativity and the implementation of new ideas (Amabile et. al. 1996, Politis 2005) as strategy.

Creativity has a rich cultural context, as ideas and solutions take place within a cultural environment that embodies a sense of meaning to those living within it. Culture immerses individual within language, numbers and scripts, music and entertainment, a national sense of humor, a culinary style, its own rituals and taboos, laws, heroes and villains, myths and legends, values and sense of success, etc. Creativity over time changes the way things are done which affects symbols, traditions and meaning within a culture. Creativity is the means by which a culture evolves (Csikszentmihalyi 1996, P. 9). Creativity and culture cannot be separated.

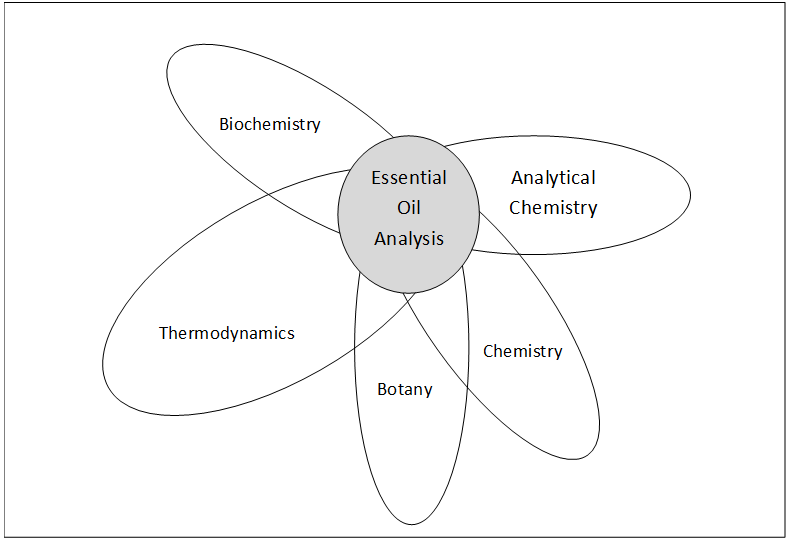

Creativity is selective and not necessarily a general trait. Creativity also tends to be domain specific rather than a trait that can be applied across other domains, i.e., a person may be a creative chef but not a creative painter or artist. Creativity can occur within a selective discipline when a person develops knowledge of the domain and its symbols. The person must also develop a cluster of skills that are unique and relevant to the domain, i.e., for painting, sight, strokes, spatial, etc. In addition to specific knowledge and skills, a person must have sensibility, interest, imagination, curiosity and being willing to experiment within the domain to be creative (see Figure 4.1.).

Figure 4.1. Creativity is Domain Specific: The elements of creativity for a perfumer.

As creativity can be seen as both a process and product, it becomes a concept very close to innovation. If innovation can be seen as the introduction of new things, ideas or ways of doing things[1], then innovation can be seen as the product or application of creativity. Somehow creativity occurs out of the interaction between an individual (or group) and the environment where it may be possible to identify something that can be acted upon (an opportunity). The conclusion or decisions made are the result of complex interactions within the environment by actors, inventions and events. For example, it is decisively difficult to identify who created commercial aviation, the post office, the communications industry or the entertainment industry. Was it one person, one event or a collection of many complex interactions, inventions and innovations that created a stage for potential new opportunities to be discovered?

Who are the people that perceive and exploit opportunities? Are they people with lots of ideas or others with more experience and creative insight into how to develop successful implementation strategies? The answer to this may be seen in the time it takes many Fortune 500 companies to turn an innovation into something that has value and provides an above industry average return (Wadhwa et. al. 2008). It is not an overnight occurrence. Many people may have the same idea but not all people have the same ability to implement and exploit it successfully. Creativity is a definite element in the exploitation of profitable opportunities (Shane and Venkataraman 2000).

The importance of creativity in enterprise lays in opportunity recognition, discovery and construction. Creativity is further required to develop realizable strategies by coupling resources, capabilities and networks together, and implement them and solve problems along the way. Creativity is also a path to flexibility which is needed in a dynamic environment. The ability to be flexible is also the ability to develop a competitive edge in the marketplace. Flexibility is also needed where problems have very little or no precedent (Proctor 1999), where one can break out of existing patterns and see new perspectives that may provide insight into solutions.

Certain characteristics must be present in a person and the situation must be conducive for a person to be creative. Creative thinking must be merged with logical thinking and reasoning, to solve many problems, as we will see in various problem solving processes. Our future is tied to creativity. This chapter will now look at all these issues in more detail.

The Cognitive Aspect of Creativity

As mentioned in chapter three, new methods available to monitor brain functions have greatly improved our understanding of how the brain operates in leaps and bounds. The frontal lobes, located in the front of the temples are very important to the function of creativity. This is the most recently developed part of the brain in our evolution and makes up approximately 30% of the cortex’s total surface.

The frontal lobes are larger in humans than any other primate and posses a large number of complex and reciprocal connections with the rest of the brain (Stuss and Benson 1986). It is believed that the frontal lobes fulfill an executive function within the brain to aid complex behavior that requires simultaneous integration with information flow. The frontal lobes help us maintain attention to tasks and manage the switching over to other tasks as required (Koechlin et. al. 1999). The frontal lobes are where thought and action is initiated in response to non-routine challenges. They also integrate cognition and emotion through the recall process, retrieving the memory of specific past events and the emotion attached to them. This emotion is used in imagination about similar events in the future. The frontal lobes allow us to move through time in a virtual manner and manipulate objects, people and events. This is important in the construction of opportunities and contemplation of implementation strategies. The Frontal lobes appear to be the key to our self awareness where cognition is integrated with affect and emotion (Wheeler et. al. 1997). The frontal lobes are also important to humor which as we will see uses some of the same processes that creativity uses. The frontal lobes are the source of our intuition or ‘gut feel’.

The neural circuits that process information for non-creative activities are the same circuits utilized for creative activities in the frontal lobes (Dietrich 2004). Novel combinations of information are created from information possessed in other parts of the brain. Creativity also requires control over short term memory, sustained attention, cognitive flexibility and judgment, which are also functions of the frontal lobes.

The right brain hemisphere also plays some role in problems that require insight and spatial perspectives and where re-arrangements are of information are required (Bowden and Beeman 1998). The functions of the left and right brain hemispheres are discussed in more detail later.

How we see the Environment through Mental Models

The environment is so rich and complex that we need methods to simplify what we see to give it meaning (O’Connor and Seymour 1995). We make these simplifications, general sense and meaning about the environment through the mental models we develop. These mental models can be defined as deeply ingrained assumptions, generalizations, and even pictures or images that influence how we see and understand the world and how we take action (Senge 2006, P. 8). Mental models are the brain processes we use to make sense of our world. They mould the thoughts we have, develop our sets of heuristics, and contain our biases, ethics and philosophies. Our mental models decide how we perceive the external environment, where our attention will be focused, and how we will respond to particular situations. Our mental models affect all aspects of our lives including, our views of the world, our career, relationships, dreams, ambitions, opinions and quality of life. Mental models exist in a hierarchy from a general overall mental model (the total set of our schemata), to our philosophical and ethical models, personal belief mental models (individual or clustered schemata), to specific task mental models (or scripts).

Our mental models begin developing at birth. Infants begin to make sense of the world from genetically inherited instructions, incoming stimuli and early experiences. The infant recognizes their mother early on as a source of food and nurturing, and their father and siblings over the first few months of their life. The infant’s comprehension, and consequently ability to develop a deeper relationship with their immediate family, depends upon the development of their mental models. This continues to develop into adulthood and throughout the rest of his or her life.

As the infant continues to grow into a toddler and child, she builds upon her mental model by adding more and more information to create deeper meaning. Mental models allow a person to learn through the creation of a holistic picture of the environment, complete with feelings and emotions. Without a mental model there is no ability to learn. During the early learning periods an infant’s curiosity and attitudes to learning develop. This is why infants marvel and get excited over sensing, touching and seeing new things that we take for granted.

The mind creates an internal world of its own, parallel to our external world. Our internal world is consistent and complete, unlike the external world that is complex and not totally comprehensible. Most of what we absorb through our senses about the external world is discarded, as external information is blended with relevant internal information for us to make sense and meaning of the external world (Wind and Crook 2006, P. 9). As we saw in chapter three, perception is not a linear process of information reception, processing, storage and recall, but a very complex, interactive, subjective and evocative process. Therefore how we make sense of the world is through our mind relying only on stimuli from the external world to a small extent. We believe what we see, which primarily comes from our internal world.

Our mental model is a configuration of who we are, our identity, which is drawn from our experiences, stories, images, relationships and learning. In this way our identity is socially constructed and immersed within our mental model. Thus our mental model controls how we react to situations and how we behave. Thus through the structure of our mental model we are trapped into the perceptions, views and behaviour that are embedded and associated with our ways of thinking and interrelationships with others and the environment.

Our views and actions are shaped by our models that govern how we act. For example, if we believe people are basically lazy and untrustworthy, we would manage a work situation under strict controls. If we believe growth is fundamental to a business, we may pursue a path of growth which would have the predictable elements of developing new products and new markets within a competitive environment. Other potential creative strategies will not be seen or be dismissed without consideration, as the views formed by our mental model would prevail, preventing learning and change. If we managed an airline, under a rigid mental model we would tend to seek growth through standard industry practices, not considering alternatives. Being an innovator and seeking entry into the developing the low cost market segment would not be an acceptable strategy, until our mental model changes and we see the benefit of doing so, through realization and learning instigated by competitive shock.

Mental models affect how we see. Two people looking at the same object or situation may see something different depending upon their mental models. This is very obvious in the political arena where different commentators based on their own political biases may interpret the same event in different ways. For example a ‘left’ leaning politician may extol the need for social benefits for unemployed people, while a ‘right’ leaning politician may dismiss the need for benefits for the unemployed because they are seen as being unemployed by choice and labeled as lazy. Essentially elections are fought on different sets of policies or mental maps. Thus vision is bounded and structured within a particular set of beliefs, focusing on different issues and policies that are important for each candidate and party. This bounding and structure prevents an individual seeing other views.

As we have seen in chapter three, it is very easy for cognitive traps and psychosis to become part of a mental model which will distort a person’s perception of the environment and their reasoning.

When a person looks at the environment there is a complex number of factors that need to be perceived and understood for meaning to occur. Each individual factor has a meaning and together with other objects creates complex field of inter-meanings. Any environment has the following factors;

· A field,

· Objects within the field,

· Relationships between objects,

· Actors,

· Relationships between actors,

· Events,

· Relationships between events,

· Relationships between actors and events,

· Relationships between actors and objects,

· Relationships between actors, objects and the field,

· Relationships (or no relationships) between everything,

· The situation,

· Movements and stillness,

· motives,

· relationship between self and the actors, objects and the field, and

· Interpretations of the above.

The variables back in the opportunity gap (see figure 3.32.) can be seen in terms of the above factors to better understand their dynamics and inertia. There is the potential to discover connections between the various field elements. Where one can see interrelationships and trends, where movements and opportunities can be discovered and constructed. However when we are immersed within the system itself, it is hard to see the dynamism of the elements of the field and we act in a similar manner to others as we cannot see any change (Senge 2006, P. 42).

Our existing knowledge can constrain and keep us within our existing bounds of thought. It is only when a person can be aware of their own mental model that they can see and think beyond it. When one is free of their mental model, new connections between unrelated actors, objects, events and the field can be seen. Through imagination new potential realities can be formed internally leading to change in the existing mental models. This is the point where creativity flows and innovation may occur.

An opportunity is thus a person’s unique perspective, scenario, future reality, which the person feels can be created. Potential changes that can occur like the shifting from a production to consumer perspective, going from a top down to a bottom up approach taking up internet journalism and self publishing, changing a diet, etc., are all examples of changing the arrangements between actors, objects, events and the field. As the environment continually evolves individuals seek change and others accept or reject it. Changing mental models is thus necessary for survival. Mental models both help to create and limit opportunities.

Somehow perceived opportunities must influence our sense of identity for action to occur. Without this influence any perceptions will just be passing thoughts. When we are aware of the restrictions of our mental models, imagination becomes an instrument of virtual reality. Imagination is a way to see the consequences of potential future actions, and take action upon them.

Changing mental models has been an important theme in management literature over the last three decades. Mitroff and Linstone (1993) espoused the need to challenge key assumptions and move from old thinking to unbounded systems thinking. Peter Senge (2006) places importance on mental models for personal and organizational learning. Russell Ackoff (1981) espouses the importance of challenging fundamental models, starting with a desired end, working backwards to the goals and objectives to reach it.

Motivational Trigger

When an individual has some form of vision, tension begins to build up within his or her psych. The gap can create positive or negative feelings. When positive, a person will feel ambitious, energetic and ready for a challenge. When negative, a person will feel powerless, distraught, think negatively and may lack self esteem. A positive effect of the gap between a person’s reality and vision is the creation of a source of psychic energy that will drive an individual’s creative curiosity. This is the tension needed to help drive the creative process.

A gap based on delusion or fantasy about something that cannot be realistically achieved will usually result in a person having to self justify their personal failings. This may manifest itself in external blame or feelings of low self esteem and self efficacy. A person with no gap between their reality and vision will not have any feeling of need to be curious about anything and will have very little urge to think about new possibilities as they accept the way they are.

Tension built up in a person because of the gap between their personal reality and vision can be released in two ways. The first way is to achieve the vision thus closing the gap being the most desired solution. This release will take a period of time to bring reality in line with vision, providing a wide range of emotions during the journey which include a sense of challenge, excitement, and passion on one side and frustration, impatience and contemplation on the other side. The second way to reduce the tension is by lowering the vision, which leads to disappointment, low self esteem, anxiety, and a feeling of powerlessness. The vision may incrementally decline to repeated poor achievement within a domain that a person has a vision. This may result in the individual slowly lowering the expectation and explaining the failing away, i.e., coming 4th was good enough.

Tension created by the gap can create positive energy. The vision acts as a motivator, something that creates a frame of positive feelings which creates a good environment for creativity. However, deep within our psych, people have self doubts about being able to achieve their visions. There is a dormant belief that we are unable to fulfill our desires because as children we learn our self limitations[2]. This is important to our self preservation and ultimate survival that continues into our adult life (Fritz 1989). Thus this leads to another deep unconscious assumption that we cannot always have what we want, which can create a deep inner feeling of worthlessness. So vision on one hand creating a feeling of challenge and excitement and a deep feeling of worthlessness on the other creates a paradox where our personal energies can be channeled in a number of ways. This paradox can lead to a loss of psychic energy where we decide to let the vision erode. Alternatively we may question whether we really want the vision and psychically manipulate ourselves into greater efforts to pursue it. Finally we may find (or sub-consciously create) obstacles as an excuse for our failure to meet the vision. Our deep assumption of self limitation may lead to a fear of failure, which in the extreme could lead to the avoidance of challenges. Alternatively this paradox may lead to total focus and dedication, where all obstacles can be overcome. Focus and lots of reserves of psychic energy can in the extreme lead to compulsive behavior, which may be good for achieving visions but have secondary costs associated with success like a neglected and failed personal life[3].

When there is a strong belief that a vision can be achieved, psychic energy will increase as clarity and success reinforces the belief in successfully achieving the vision. The strength of the belief in success has more “gravity” than the person’s deeply held assumptions of worthlessness. However when things don’t go well and there is personal doubt about achieving the vision, psychic energy greatly decreases and the “gravity” of the deep assumption of worthlessness is stronger than that of the vision and pulls the person towards giving up. This is depicted in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2. The Forces of the Motivational Trigger

Creative Sensitivity

The environment is full of a complexity of consistencies and inconsistencies, discontinuities and disparities concerning objects, people and events in life. Our association with the environment is also a complex one. The relationship between our self and the environment is full of peculiarities and subtleties of meaning, if we are sensitive enough to pick them up. Creative sensitivity is related to our ability to perceive and understand the complex situations we observe and are involved in. High creative sensitivity therefore implies that we are more observant and aware of the things around us and feel comfortable with the complexity rather than trying to simplify meaning according to the perceptions we have (Hicks 2004, P. 45).

People who can perceive the richness of the environment have higher levels of creative sensitivity and should therefore be able to pick up the relevance of seemingly random facts and information. They will be better placed to make connections between them than someone who is less sensitive to the environment. Creative sensitivity is an important precondition to creativity.

In order to solve problems it is necessary to be able to perceive them. This is not a uniform characteristic across the population and some people are more endowed than others. Creative sensitivity is believed to be something people are born with (Eikleberry 2007). Creativity partly relies on external stimuli to act as cues to assist in long term memory recall. Creative sensitivity coupled with defocused or general attention to the environment will pick out subtle cues which will aid in the recall of prior knowledge, experience and information deeply locked away in the long term memory (Dewing and Battye 1971, Dykes and McGhie 1976, Mendelsohn 1976, Martingdale 1977), aiding the associative process and imagination. Therefore people with low creative sensitivity would not pick up as much stimuli from the environment as someone with high creative sensitivity, which will result in a lower number of cues to stimulate recall from the long term memory.

The characteristic of creative sensitivity gives a person some heightened sensitivity to some aspect of their life. Creative sensitivity is usually restricted to limited areas, such as, colour, pictures, sounds, music, values and ethics, human behavior, empathy, spiritual and spatial dimensions, etc[1]. People’s sensitivity also ebbs and wanes during the day, month and different times in a person’s life[2]. At mean levels of creative sensitivity, a person will tend to perceive more in their area of sensitivity endowment and experience subtle satisfactions or disappointments concerning certain pieces of art, music, performance, etc. Pleasant appreciations can lead to increased vigor and energy in a person’s area of sensitivity. This leads a person to have good intuition in their particular areas of sensitivity. However, one may become bored or impatient with ordinary and mediocre things within their area of sensitivity. Too much creative sensitivity on the other hand can lead a person to suffer pain due to empathy, as nothing will satisfy their expectations. This can lead to deep emotions, i.e., feeling pain for the poor, and in the extreme, feelings of depression and lethargic states.

Creative sensitivity assists a person develop a deeper understanding of their area of sensitivity than what the average individual would. Consequently a sensitive person becomes aware and concerned about what is wrong within their area of sensitivity. This is where creativity begins, with the finding of a problem. Only after sensing that there is a problem can a person put their attention to solving the problem. Creative people focus on what is wrong, out of place, missing, not complete, lacking something, knowing that something needs to be changed for the better. Problem solving is not the centre of creativity and not the process that actually creates the opportunity. It is the finding of the problem and the way a person mentally structures it that creates the birth of a potential opportunity.

Focus and Attention

Another important prerequisite to creativity is focus and attention. Focus is important for the selection of what information coming in from our senses we concentrate on, i.e., what cues we select for attention. Attention determines our concentration on what information we decide to put our mental effort upon to process and understand. We are continually bombarded with so many different kinds of perceptual stimuli, where we must decide what to take notice of and what to ignore. Our attention to selective information is the way we allocate our cognitive processing effort to information we perceive. Focus and concentration are very important characteristics to prevent the overloading of our limited cognitive processes.

A key characteristic of attention is that it is limited and we are simply unable to process all incoming information at once. In chapter three we discussed the bottleneck where only some stimuli/information is allowed through into our conscious awareness at a time. To recall this, take for example looking at a street scene. You will see the whole picture, but not be focused everywhere at once. Our mode of sight is like at spotlight on the middle of the picture (Posner 1980) and anything we see around the periphery gets much less attention. This is termed spatial attention. If we are looking at the scene and a neon light starts flashing, it will involuntarily capture our attention. This is called attentional capture, where a person’s attention is involuntarily drawn by some stimulus. This is perhaps a leftover from our primal programming to ensure that we can spot any immediate danger quickly. As we look at a general scene our head may remain stationary but our eyes will move more and focus on different objects for short periods of time (<1/10 sec.). This is called object-based attention (Cave and Bichot 1999). We can give attention to objects in either of these attentional modes (Soto and Blanco 2004).

Attention is also important with auditory stimuli where we are only able to focus upon one message at a time. There will be little awareness of the content of any other messages, however we will be aware of some of the message characteristics such as pitch, but not content (Moray 1959). This phenomenon can be experienced at a party where many conversations are going on at the same time, but an individual has trouble focusing on anymore than one conversation at a time, just hearing pitching and droning in the background. This is an example of selective attention, as the other conversations are not processed for meaning.

However some studies mid last century showed that individuals can be distracted by cues that divert their attention from one piece of information to another. Treisman’s (1960) research supports this postulation, where subjects were asked to wear a headphone where two separate mixed up messages were spoken through each side of the headphone. Many subjects switched their attention halfway through the messages from one ear to the other and were able to recite a meaningful message, made up of the two mixed messages. This infers that our attention is also influenced by cues, which can displace attention.

Attention is also the device through which we commit our mental effort necessary to initiate cognitive processing. Attention is manipulated to assist us consider, examine, and respond to outside stimuli in an appropriate manner necessary for a person to carry out daily activities. Attention allows us to allocate our short term working memory time between the various tasks we undertake. We have a certain amount of choice in this matter through deciding on what we want to perceive. This partly regulates what we identify and interpret for given meaning to through cognitive processing.

In daily life we are engaged in multiple tasks like walking, talking, reading, eating, writing, playing, and watching TV, etc. Doing some of these tasks concurrently requires giving them divided attention. This requires multiple focuses which will lead to the decline in individual task performance. Research into multitasking activities such as driving a car and talking on a mobile phone at the same time, shows that driving response times are substantially longer than if a person was just driving a car (Beede and kass 2006). This occurs due to the bottleneck theory and limited short term memory capacity, discussed in the section on cognition in part II.

As we have a limited attention capacity and use it to undertake all the various tasks we need to do, there will be no surplus capacity left for undertaking other cognitive tasks. Creativity relies on having surplus attention available. People occupied with busy jobs would tend to have less capacity than those with idle cognitive time that can be utilized for creative tasks. However, when tasks become automatically processed, i.e., without the need for conscious awareness, the mental effort required to undertake these tasks diminishes (Borgh and Chartrand 1999). This frees up cognitive resources and allows concentration for other tasks. This can be understood best through the example of learning to ride a bicycle. When learning to ride, initially a person’s full concentration is required. However once one has practiced, has some experience and developed riding skills, less concentration is needed. Under such conditions mental effort can be put into other tasks like the incubation of ideas, where insights can occur, discussed later on in the creativity process.

Attention is an important mechanism in the creativity process and is influenced by situational and other factors. Our existing patterning processes and routines tend to control our attention and thus suppress potential insights into new ideas. The patterns we use become polarized and therefore self perpetuating, where other stimuli is ignored, as our attention is focused on existing patterns.

Generally speaking the capacity for attention, particularly multitasking declines with age (Hartley 1992, Kramer and Larish 1996). However older adults who have strong skills and experience in a particular area will be still able to multitask, regardless of their age (Jennings and Jacoby 1993). For example older people tend to perform better than younger less experienced drivers in talking and driving simultaneously (Strayer and Drews 2004).

In regards to environment, rigid, tradition based, authoritarian and collective cultural environments tend to suppress the development of insightful ideas, as these types of societies do not welcome them. This leaves little incentive for people to give attention to new connections and ways of doing things. Thus creativity within oppressive cultural situations requires enormous amounts of attention to be able to break out of traditional patterns and develop new insights (Csikszentmihalyi 1996, P. 9). This also occurs in organizations that are bureaucratic and follow rigid procedures (Leonard 1998).

Attenuation

Treisman (1960) postulated that unattended acoustic information is not completely blocked from our filtering and patterning during the attention phase. These stimuli are weak, but nevertheless make it into our cognitive system, where it is enough to trigger recognition and maybe stored in the long term memory. Other theories like Deutsch and Deutsch’s (1963) late-selection theory postulates that all incoming information is identified, but only the selected piece of information emerges into phenomenal consciousness.

Although these theories are related to acoustic attention, it could be surmised that more information than we realize flows into our long term memory, which can potentially be utilized in the sub-conscious incubation process discussed later within the creativity process.

Imagination

Imagination is the ability to form a mental image of something that is not perceived through our senses. As we examined in chapter three, imagination is the ability of the mind to build mental scenes, objects, or events that do not exist, or are not present or happened in the past. As we have seen, memory is a manifestation of imagination and we use imagination in almost everything we do. Imagination is a useful planning tool where we envisage the conduct of future meetings and events. Although imagination builds upon our knowledge, knowledge alone cannot create imagination. Imagination is a product of our creative intelligence, and as such, a powerful tool to visualize and understand potential scenarios that we may plan for the future. In this way visualization or mental imagery is something similar to intuition or insight and is vital to the creativity process.

Imagination is also a tool for the development of determination and courage to follow through on visions through repeated mental rehearsal in our minds. As mentioned again in chapter three, an athlete will go over a race time and time again to mentally prepare him or herself for the mental and physical effort they need to put in and predetermine all the potential dangers that may prevent him or her from achieving their goal. Imagination enables the athlete to recognize difficulties and develop enough resourcefulness to solve any potential and expected problems before they occur. Imagination also boosts a person’s desire by helping a person experience what it would feel like to succeed.

Any consideration a person makes about something requiring a solution requires imagination to manipulate memory. Imagination is a process that can combine past experiences, knowledge and feeling into new images and concepts. In this way new connections made between bits of knowledge and past experience create novel concepts. Imagination is not totally a conscious process. It may also incubate sub-consciously when a person has surplus attention to focus on recombining memory and external stimuli into new mental images. Imagination plays a major role in the creation of new ideas.

Imagination is not only a contributor to the process of creativity it is also a manifestation of creativity. We use imagination whenever we are designing something like a dress or a building, developing a new product or landscaping a front yard of a house. Imagination links with many other creative aspects such as humor, metaphor and analogy, vision, memory, developing understanding, learning and empathy. Imagination is the tool we use to extrapolate concepts into ideas and opportunities into strategies.

Imagination does not generate completely novel and new to the world concepts. As Einstein once said, “the secret of creativity is knowing how to hide your sources”. Anything novel we come up with through our imagination and insight is based upon our prior knowledge and past experiences. Thus inadvertently much of the novelty we create in anything is likely to be based upon something that existed previously, be it in another domain or field that an individual has exposure to. This is what Marsh and bower (1993) call inadvertent plagiarism. Therefore it’s likely in most cases that novel creations are inspired by something in the past, although through imagery, the concepts may have been given new types of manifestations. However through the imagery of analogies, many breakthroughs in science have been achieved (Shepard 1988). For example, Einstein developed his insight for the theory of relativity through imagining what would happen if he travelled at the speed of light, Faraday claimed to have visualized force lines from electric and magnetic fields giving insight into the theory of electromagnetic fields and kekulé reported that he discovered the concept of the molecule after he imagined a snake coiled up in a circle.

Curiosity

Curiosity is an emotion we share with many animals. Curiosity sparks inquisitive behavior and is another important aspect of the creativity process and is also an important part of our learning. Curiosity is a trigger and a drive that leads to the development of an interest, love or passion for doing, investigating or exploring something.

Curiosity begins at the moment of birth where we start to explore the world as we know it. Our curiosity fuels our ability to learn and develop as human beings in a social environment. Curiosity continues through our infancy, adolescence, teenage and into our adulthood driving us to seek new knowledge and understanding about our surroundings, and relationships, etc. In our early life we begin to understand basic concepts through our exploration and discovery, where we begin to find domains that we have interest in. For example as children we play with insects, dig tunnels, fly kites and build model planes, where one or more of these interests may continue into our adult life. Many things we learn such as the lifecycle of insects and through analogy, enables individuals to understand that all living things have limited lifecycles. Through continuous discovery during our early years individuals learn about life, science and society.

Certain activities we undertake will create a certain level of excitement and an individual will spend more time within the domains they are excited about. Strong curiosity leads the development of new skills in the domain of interest. Through repeated use of these skills an individual begins to develop mastery within a domain, a common trait among many notable public figures who have made breakthroughs in their domains of interest (Gardner 1993). It is mastery that develops potential in individuals. Mastery separates great individuals from the rest, where those who have mastered their domain have the potential to make great insights about their field of interest. Personal mastery usually contains personal vision, a much stronger dedication than others in their field of interest, a passion for more knowledge and a deep love for what they are doing (Senge 1990). Mastery brings spiritual development to a person where they become self assured, confident, secure, with a deep sense of purpose about themselves. This is all driven by a person’s passion for the domain.

Figure 4.3. True personal mastery is rare in people.

Curiosity consists of two separate elements which are paradoxical. On one side curiosity brings openness and willingness to learn, but on the other side it brings obsessive persistence. Both these elements are important if we want to master a domain, to question things and develop new ideas. The elements of curiosity promote an active cognitive system which through this paradox is able to look for connections of different information within the domain. Curiosity maintains an active cognitive system which becomes more proficient in seeking connections through learning as time and dedication goes on. The ability to gain insight takes time as it is not a short term or immediate activity. Mastery is a necessary ingredient which takes time to develop. The cycle that curiosity sparks in creativity is depicted in figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4. The Process of exploration, discovery, mastery and insight that curiosity ignites.

Without curiosity people will lack the passion needed to engage domains, seek further knowledge and wisdom. They will become apathetic and settle for an incomplete understanding of things. Lack of curiosity will lead us to missing information in the environment which will hinder our ability to develop new ideas, i.e., suppress our ability to be imaginative.

When curiosity develops a high spiritual level within us, we will start pondering upon the complex questions of our existence such as; ‘Where do we come from?’ ‘Is there life after death?’ ‘Is there a supreme-being, force or god?’ and ‘What exists in the universe besides us?’ This role that curiosity plays in our spiritual life through our imagination and fantasy leads us to new possibilities, excitements and sense of spiritual purpose.

Prior Knowledge

As we saw in chapter three, prior knowledge is knowledge that accumulates in our memory from previous experiences. As our memory builds up this knowledge our capacity to learn and generate new ideas increases. Prior knowledge influences our modes of perception[1], focus of attention, modes of reasoning and beliefs about knowledge. Much of these influences are socially or culturally biased within the domain and field we operate within (Latour 1987, Knorr 1981). We think in the metaphors and analogies that are based in our socially impregnated prior knowledge (Einstein 1950). Most of our ideas are based on everyday knowledge of our domains and fields that we are surrounded in (Wertheimer 1982, Miller 1986).

We construct our ideas and meanings from incoming perceptions and the images and metaphors of our prior knowledge (Lightman 1989, Miller 1986). Piaget’s theory postulates that new knowledge is the result of combining of new experiences with our prior schemata (Inhelder and Piaget 1958). In this way new knowledge doesn’t replace prior knowledge, it reuses and refines it, restructuring it into something different[2]. Conceptual change only occurs slowly where prior knowledge is restructured to encompass new ideas (Toulmin 1972), that are really variations upon an interrelated system of knowledge. Our schemata start developing from childhood and continue to develop throughout life, slowly developing conceptual change to the ideas we have (Piaget 1970). As we mature our ability to make sense of the knowledge we have improves with the enhanced reasoning tools and capacities we develop (Corsini 1994). Thus prior knowledge is paramount in how we make sense of our interactive experiences. So our knowledge grows with the assimilation of new perceptions with prior knowledge in our existing schemata.

For the reasons above, prior knowledge is important in problem solving as it influences our search procedures and heuristics to guide the search (Newell and Simon 1972), as we look for analogies and similarities with what we already know. Prior knowledge also assists in comprehending a story through construction with information and ideas we already have. Prior knowledge thus acts as a filter as to how we see things, interpreting our perceptions according to what we tend to believe. Research has shown that jurors’ decisions are often based on how information is presented to them. When information tends to be consistent to what they believe through their prior knowledge, they will tend to make their judgments on prior knowledge rather than new facts (Carlson and Russo 2001). Prior knowledge will influence people to stereotype objects, people and events. For example, African Americans tend to believe in stories of police misconduct and bigotry, because of their backgrounds, than White Americans (Hastie and Pennington 2000). In fact our prior knowledge is made up of both fact and belief.

Figure 4.5. Our Prior knowledge is made up of both truth and beliefs

We develop two forms of knowledge that are important for the creativity process. The first is domain knowledge, which relates to a discipline like mathematics, astronomy, cooking, music or poetry, etc. Each domain is clearly defined with its unique sets of rules, syntax and symbols. It is domain knowledge that helps an individual develop mastery within a discipline. Without in-depth domain knowledge it is very difficult for a person to develop insights in that particular discipline. Mastery of one domain enables an individual to extend into adjacent domains. For example, a scientist with knowledge in pharmacy may be able to make contributions in the domain of biochemistry or biotechnology. Creative insights can come from emerging from one domain to another. Experts within domains have a larger knowledge base from which to work that enhances their chances of being creative, relative to novices in the domain. However, although domain knowledge is very important to creativity, narrow focus within a single domain can create tunnel vision and hinder creativity. The second area of knowledge is the field, which can be as large as society itself, or as small as a few people or corporations[1]. The field requires a certain amount of social capital to be accepted and recognized within[2]. The sum of domain knowledge determines what can or cannot be done in the field, as innovation within the field will come from a specific domain. Fields have profound effect upon creativity. A field may be reactive or proactive in the pursuit of new knowledge and differ in attitude towards novelty.

Through prior knowledge we tend to be a product of the various influences upon our lives. Our thoughts tend to reflect this in some way, where ideas, information and knowledge from the society we are immersed within has a strong influence upon us. From this point of view prior knowledge is culturally and domain biased. Our ideas are based on familiar knowledge that through syntheses creates something unfamiliar and seen as novel by our society. Margaret Boden (2004) in her book The Creative Mind describes how even the most creative people have adapted ideas from the works of others through some form of syntheses[3].

Prior knowledge is very important in the creativity process, although it may have a positive or negative impact. Specialized domain knowledge is very important in both the creativity and the opportunity discovery process. It enhances the chances of finding new associations and connections. However the rigid patterning that develops from prior knowledge can restrict both the way we perceive the environment and way we look at information and problems, thus restricting our capability to make associations between unrelated pieces of information.

Emotion, Affect and Creativity

Our emotions and feelings to some extent influence our thinking and behavior. For example if we are excited about undertaking a new course of study, we will look forward to going to class, undertake our study and do our assignments with enthusiasm because we may believe that this course of action is good for us. Likewise many of us fear going to the dentist and will be inclined to try to put visits off unless it is absolutely necessary. Our emotions and feelings play a role in our decisions and subsequent behaviors. In fact a great deal of our behavior is based on irrationality such as getting into fights, bad moods, getting angry with people, stereotyping people and disliking certain events and things. These behaviors can make us inconsistent, ignore relevant information, deceive ourselves and jump to conclusions, etc. This influence is stronger when we are not aware of our emotions. When emotions exist sub-consciously, they may exert much greater influence and even rule our decisions and behaviors (this issue is discussed in more detail in the section on psychotic states in chapter three. Our emotions and how we feel about things affect decisions we make, our ability to recognize opportunities and our energy levels to commit and do things.

Emotion influences how we rate the importance or intensity of various events in our life. This is terms affect intensity. People with high affect intensity see events more intensely than those people with low affect intensity. For example, where an event is rated as moderately good by an average person, a person with high affect intensity would rate the event as extremely good. Likewise where an event would be rated as moderately bad by an average person, a person with high affect intensity would rate the event as extremely bad. Individuals with high affect intensity are more reactive to emotion producing events in their lives, whether they are good or bad.

Although mood change is a normal aspect in life, high affect intensity individuals would tend to exhibit more mood variation than other people (Larsen 1987). Mood change influences personality, sociability and arousal to environmental stimuli. High affect intensity individuals tend to have vigorous and energetic lives, tend to be more outgoing and sociable and tend to seek out more stimulating and arousing things around their lives. They shun boredom and will look for things to do even if what they do is antisocial (Larsen and Buss 2005, P. 441). Extreme affect intensity can be seen as neurotic extraversion (Cooper and McConville 1993).

The relationship between affect intensity and creativity is inconsistent and probably depends upon the type of emotions and situation. However in general positive affective states can enhance creativity where negative affective states can inhibit creativity. There is much anecdotal evidence to show that positive emotions do assist in the creativity process. The mathematician Henri Poincare is reported to have experienced creative breakthroughs while on vacations and Mozart claimed that pleasant moods were the most conductive to his creativity (Vernon 1970).

Affect-laden thoughts may enhance the ability of the cognitive retrieval processes to recall affect-laden information from the long term memory. This may emerge during our thought process, fantasy or imagination (Russ 1993, P. 12). Affect may assist in focusing an individual to affect states, i.e., areas that are intensely important to the individual (Russ P. 13). Affect may also manifest pleasure to the individual engaged in the challenge of discovering problems, working on solutions, gaining insights and seeing them develop into opportunities in their domains and fields of expertise. This intense pleasure could be described as passion. Fredrickson (1998, 2001) postulated that positive emotions such as joy and love broaden a person’s repertoire of behavioral scripts, enabling them to pursue novel and creative paths of action. This is supported by empirical evidence of a number of studies that show that positive affect can induce changes in cognitive processing that facilitate creative processes in individuals (Amabile et. al. 2005).

Other studies have shown that negative affect can also lead to greater creativity in some areas. Ludwig (1992) found in a study of 1,000 prominent individuals from almost 50 different professions that there was some evidence of a correlation between depression and the level of creative achievement. Other studies have shown that many highly creative individuals had affective disorders, primarily bipolar illness and depression (Feist 1998)[4]. Negative affect can also be a signal that something is amiss and motivate an individual to work hard to find a solution (George and Zhou 2002)[5].

Another possible outcome from high affect, either positive or negative, is that these strong emotions take control of attention and absorb available psychic energy. People in a high affect state may tend to be controlled by this state. People become preoccupied with their emotions and their behavior will be aimed at dealing with their emotion (Weiss and Cropanzano 1996). Excessive emotions, positive or negative can distract from creativity and task performance.

From the cognitive point of view Martindale (1999) suggests that attention becomes focused on arousal inducing situations when strong arousal states exist, leaving no cognitive capacity to focus on making associative connections necessary for novel ideas. However the simultaneous experiencing of positive and negative emotions may stimulate creativity by increasing the breath of cognitive information available, where a given complex mood may active numerous memory modes. Mixed emotions may develop crossovers of memory modes which bring new associations and novel ideas (Rothenberg 1990, Richards 1994). Other studies found it was not the moods, but the mood swings that gave contrasts where contradictory moods gave rise to different perceptions and observations of the environment (Jamison 1993), thus increasing the variety and breath of potential associations as input for the creative process.

Positive Affect and creativity may also co-exist as positive experiences may be associated with the task of creativity itself. Creative behavior according to Csikszentmihalyi (1975, 1996) is actually a “flow state”, a merging of individual and the creative process into the one activity, which creates feelings of enjoyment and enthusiasm. Affect in itself may be a form of intrinsic motivation for creativity (Amabile 1996).

The Role of the Ego Concept in Creativity

If we combine the concepts of Jung’s ego/consciousness, Freud’s ego, id and superego with Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, we have a central ‘mind sponge’ that absorbs external stimuli and blends them with our internal knowledge, beliefs, feelings and emotions to form a singular spatial concept/image we call our self[6]. The structure of our ego concept has influence over our thoughts, feelings and emotions that govern our sense of reality, view of the world, inner drives, motivation and attention. As a consequence, our ego concept also has a great bearing upon our cognitive functioning and behavior. Although the ego concept is not directly involved in the creativity process, it exerts many indirect influences that are of an important nature.

The ego concept both makes up many personality traits and is also influenced by personality traits. Likewise both the ego concept and personality is influenced by our situational conditioning and life experience as well as our inheritance. The ego concept is the frame of reference that comprises both our personal possibilities as well as our personal constraints. The ego concept is the bridge between the external and internal, acting as both a gatekeeper and the creator and interpreter of our personal meaning. At one extreme our ego concept protects our self image by interpreting the world in a way that provides for security, but at the other extreme our ego concept seeks challenge and adventure. These interpretations and constructions made by the ego concept act as a driver for the individual. The intervention of the ego concept into our cognition is necessary for a person to carry out a normal life.

The role of the ego concept in everyday life is to provide enough motivation, ambition, self confidence, attention, dedication and morality to undertake important tasks. Without the attention and drive from the ego, a person will not look after their own survival and that of their family. The ego concept contains the inner programming to survive and provides strategies for achieving this. The ego concept provides an aggressive-destructive or a sensitive-appreciative drive to a person when facing challenging life situations. It also determines whether a person will attempt to dominate others or be dominated by others as a means to providing oneself with what they need to survive. The ego concept will determine whether a person is ego-centric or altruistic towards others. These may not be absolute and rigid strategies, maintaining fluidity for various situational encounters a person experiences.

Through these embedded assumptions and beliefs within the ego concept, incoming information is judged as to its significance to survival and self image. The ego concept defends against any threatening realities manifesting themselves through panic, rage, anger, hate, or guilt, etc, in response to any situation that is challenging and cannot master (Hart 1950). Within the realms of normality, threats will lead to thoughts, feelings and emotions and then judgments, but if the ego concept overwhelms the psych with emotion, then there are risks that the ego concept becomes unbalanced and dysfunctional leading to psychosis, as discussed back in part II of this book. Balance of the ego concept is important to a person’s libidinal love for what is outside. Psychotic unbalance will turn a person inward into their internal world, taking over all the limited attention a person has for other activities. This may lead to a decline in curiosity because of the attention to selfish goals (Csikszentmihalyi 1997, P. 345).

The functions of the ego concept are very important in providing some of the positive psychic positions needed for creativity. The ego concept provides strong motivation and sense of achievement that enables people to undertake challenges where creativity is needed (Aguilar-Alonso 1996). This allows a person to challenge existing realities, where they are not satisfied with ‘what is’. From Bourdieu’s point of view, entrepreneurs are not in a state of doxa, and consequently don’t accept the realities of the field, thus the habitus and the field are out of alignment. This unstable subject-object relationship requires some form of creativity and innovation to bring some new form of alignment. This motivates or drives a person to desire and seek new realities, rejecting the status quo of today.

From the point of view of psychoanalysis, the insight needed in creativity is intuitive perception that is the result of unconscious synthesis (Hart 1950, P. 14). We are inclined to overestimate the conscious aspects of creativity. Therefore much of the creativity process occurs within the unconscious and what we perceive unconsciously vastly outweighs what we perceive consciously. Through the interchange of conscious and unconscious perception we develop either original creation or psychosis depending upon the balance of our ego.

An unbalanced ego concept can destroy the potential for creativity and insight in a number of ways. Our basic aggressive-destructive programming leaves little room for creativity, if this is a dominant instinctual way of thinking. A person who is submissive to others for survival will usually suffer from the repression of any creativity, as he or she must accept the will of others (Paul and Elder 2002, P. 177)[7]. Although a certain amount of Ego-centricity leads to confidence, it also creates a belief that ‘one is the centre of life’ and ‘they know how things really are’. This lowers curiosity where one follows their own intuition without ever challenging it. Ego-centricity filters information in a way that is stereotyped and ‘self justifying’. It leads to self centered interests and objectives leaving little room for open mindedness. Ego-centricity leads to lack of empathy and an inability to see other viewpoints. This destroys any potential for insightful thinking, where in extreme cases the destructive forces of social prejudice, conflict, anger, anger and depression may occur. Extreme social ego-centricity prevented humankind understanding the universe for many centuries, insisting that the Earth was the centre of the universe.

Figure 4.6. The ego concept

Humour and Creativity

The cognitive processes behind humor are very similar to those behind creativity. Therefore having a brief look at the concept of humor will help us understand more about how we build up tension, make associations and develop insight, all ingredients necessary for creativity. Humor is both cognitive and emotive. Humor is created from an incongruency between what a person expects and what actually happens, which creates an element of shock and surprise, i.e., an emotional response.

Take for example the situation where a migrant just arriving in a city who doesn’t speak English well, asks for a job at a fruit stall. He gets the job and asks the owner what to say if somebody comes and asks for some fruit. The owner responds by telling him if the person asks “how much are the oranges?” to tell them “60 cents”. The owner continues and says if the person asks “are they good or bad?” to tell them “some are good and some are bad”. Then the owner said if the customer asks “do you think I buy them?” to answer “if you don’t somebody else will”.

On the migrant’s first day on the job, a lady walks up and asks “how much are the oranges?” The migrant answers “60 cents”. The lady asks “are they good or bad?” and the migrant replies “some are good and some are bad”. The lady asks “do you think I should buy them?” and the migrant answers “if you don’t somebody else will?”

A little later a man walks up and asks “how much are the oranges?” The migrant answers “60 cents”. The man asks “are they good or bad?” and the migrant replies “some are good and some are bad”. The man asks “do you think I should buy them?” and the migrant answers “if you don’t somebody else will?”

Then another lady comes and asks “how much are the oranges?” The migrant answers “60 cents”. The lady asks “are they good or bad?” and the migrant replies “some are good and some are bad”. The lady asks “do you think I should buy them?” and the migrant answers “if you don’t somebody else will?”

At 6 o’clock that night just as the migrant was closing the store a man walked up and asked “what is the time please?” The migrant answered “60 cents”. The man replied “stop joking will you” and the migrant replied “some are good and some are bad”. Then the man getting a little angry said “do you want a punch in the nose?” and the migrant replied “if you don’t somebody else will?”

A joke sets up a situation which has some imaginative scenario within it that enables us to create a certain set of images and vision within our mind. We have expectations that the story should play out in a certain way, but tension builds up. The story is heading towards an incongruency, something that is going to shock and surprise us. The rhythm and tension of the story builds up, as this is important to the shock, surprise and emotions generated. This is important to the humorous element as we are waiting for something, in the case of a joke the incongruence to manifest itself. The punch line is where the listener should develop insight followed by an emotive moment, just like in the process of creativity.

It is difficult without telling the whole joke to understand why it is humorous. The joke must be explained in full detail. We cannot point out exactly why it was funny. For a joke like the one above to be humorous to the individual, they must see the association between the punch line and their expectations. The incongruent transformation must transvaluate our values in a certain way or else it won’t be humorous. It is this transvaluation that the incongruence taking an unexpected path away from our expected outcome that made the humor. We recognize the incongruence, the link between the story and the punch line, which are unrelated until we make the association. A humorous story or event challenges our expectations in the way things are (our patterns), turning expectations upside down, where we make new connections, enabling us to see the funny side. This is the same way we make creative connections. Like creativity, humor uses knowledge through creating different patterns to create new meanings.

Without the tension building up about what we expect to happen and what may shock us there can be no humor. Just like creativity we also need to perceive and understand the situation from both the cultural and experiential aspects (prior knowledge), otherwise we will not understand the various elements of the joke (Clouse 1993).

The Creativity Process

There are vast differences in the way people reach a creative solution, develop a new idea, conceptual process or product which reflects the various differences in creative sensitivity, focus and attention, energy, imagination, curiosity, ego, empathy, confidence, discipline, experience, patience, persistence, prior knowledge, level of comfort and the environment they are surrounded in. There are also just as many theories about the process of creativity, which was pioneered by Graham Wallas (1926) in his book the Art of Thought. Wallas outlined a four staged sequential model of the creativity, depicting it as an evolutionary process of thinking. Since Wallas’s model many enhancements, modifications and variations have been proposed along this evolutionary theme. The general steps as mentioned in several theories of the evolutionary creativity model are outlined as follows.

The Engagement Period

The creative process begins with some form of puzzling situation, curiosity, questioning of something given or problem. With the correct motivation our attention and psychic energy is deployed towards contemplation of this issue. This must be triggered by some sort of personal experience, interaction with another person, feel of a need to be satisfied or some form of challenge or conflict between a personal and perceived reality. A combination of the factors discussed earlier in this part of the book influence whether or not the person will engage upon a quest for clarity and understanding and pursue a solution to the issue, down the path or process which we call creativity.

Engagement is the first step. Not all people are looking to engage in all quests and pursuits for answers to puzzles, problems and issues due to lack of need or low levels of curiosity. Not all people for the reasons that we have discussed can see the same things in the environment. Not all people can see an issue or problem to be curious about. People have different levels of sensitivity to the environment and different motivations to engage. Busy people with hectic schedules will be less likely to pick up stimulus from the environment than those with more time on their hands and greater creative sensitivity. No engagement, no creativity process.

The Preparation Period

Before a problem can be solved a certain amount of cognitive preparation must be undertaken. The preparation stage is where a person has made the realization that something is not right, does not fit, can be done better, or can be done differently. In this stage the scope, direction and depth of the problem is more or less defined in a preliminary form, for later refinement. Potential methods of solution or patterns are selected as ways to solve the problem. Potentially relevant prior knowledge and experience is also selected for recall along with the collection of new information for cognitive matching.

Once a person becomes focused and curious about the particular problem they have identified, the creativity process begins in earnest. Different types of problems take different lengths of time to solve, ranging from a very short time to many years. Different problems also require different thinking strategies and styles to solve them. Thinking about what to whip up for lunch from leftovers in the refrigerator takes up a different time frame and thinking style to a person constructing a scientific hypothesis. Some problems may be very rigid with only a limited number of potential solutions while other problems maybe open ended requiring the construction of something novel and unique to the field it concerns, such as a new product concept.

The preparation process is a period of discovery about what the problem really is, possible ways in how it can be solved and what information is relevant to the solution.

The Frustration Period

Sometimes a period during the creative process occurs where all exploration leads to dead-ends and frustration. This may especially be the case when a few attempts have been made to solve the problem. The problem may not be as simple as it first appeared and deeper implications may emerge making the solution much more complex. This is often the case in very complex problems like hypothesis building by a scientist or developing a conceptual case for a new product. Frustration may lead to a person ‘back to the drawing board’ because of the utilization of thinking strategies that did not make any headway in solving the problem. Alternately a person may abandon the problem metaphorically putting it into the ‘too hard basket’ because ‘they bit off more than they can chew’. However abandonment of the problem may not necessarily mean an end to the creativity process. Mentally retreating from the problem for either the purpose of finding another way to solve it or the wish to abandon it, leads onto another process that acts within our sub-conscious levels, the process of incubation.

The Incubation or Sub-Conscious Contemplation Period

When one has become frustrated and/or feels the problem is not worth pursuing any further, the person stops putting in his or her psychic energy into the problem thereby releasing the mental tension they have been putting themselves under. Taking a rest allows the creativity process to become sublimed within the sub-conscious. During the process of sublimation all the bits of information are digested in the mind within a set of processes that appraise, rearrange and seek to reorganize connections between the pieces of information and the problem. The sublimation of the mental processes may allow the mind some freedom from the patterning of our conscious thinking. This may be the case that some misleading information we rely upon during our conscious reckoning of the problem is dropped (Smith and Blankenship 1991)[1], some form of block is removed (Smith 1995), pieces of other information are applied to the problem which were not consciously considered, or some untried thinking strategies are utilized. This process will not begin until the conscious process stops.

The incubation or sub-conscious contemplation period is perhaps the most significant aspect of the creation process where different thought strategies occur without the explicit awareness of the person. We are not sure exactly what these processes are but we know the brain is very active during this period and strong anecdotal evidence exists where many scientists, engineers, artists, and writers often arrive at some form of realization after this process of incubation or subconscious contemplation (Wallas 1926)[2]. For this reason these processes remain somewhat mysterious to us. There may be a process of combining random or seemingly unrelated strings of information that may assimilate to some forms of connections found in prior knowledge[3]. For example, folklore states that Isaac Newton only developed an insight about the force of gravity after witnessing an apple fall from a tree he was sitting under. Incubation may allow dominant left hemisphere serial thinking to give way to right hemisphere holistic thinking processes thus allowing the problem to be seen differently. Conceptual generations from holistic thinking may ordinarily be rejected during conscious thinking because we are trying to think in a rational and logic manner. The incubation process seems to work best when a person is immersed in a different environment than usual (Smith 1995). The environment should be relaxed, out of routine and without outside stimulation like meetings, radio or television in order to allow the mind to give attention to sub-conscious processing. One situation is sleep where the brain is still very active and empirical evidence seems to support anecdotal evidence that sleep assists the creativity process (Wagner et. al. 2004). This long relaxed period may allow information situated deep in the long term memory be recalled and applied to the problem. The incubation or sub-conscious contemplation period can go on from a couple of hours to a period of months or even longer in some cases.

One way to demonstrate frustration and incubation is to look at a gestalt illustration. Figure 4.7. depicts an ambiguous picture. You may be able to see at once a young woman in the left three-quarter view. However you may be the one person in five that can see an old woman facing to the left. You may be blocked from seeing one of the figures, as you need to re-arrange and use the parts the picture to make a new picture. By sitting and looking at the picture forcing yourself to see the other perspective, you may start to become impatient and frustrated. This frustration will tend to take-over from your curiosity and if you cannot see the other perspective, stress may even be evoked within you. If you do not see the picture at this sitting, put the book down and return to the picture at a later time and the other perspective may come to you when you look at it afresh.

Figure 4.7. An Ambiguous Gestalt Picture

Recent research has shown when individuals are left undisturbed the brain is not idle, where there is actually increased activity, localized in the pre-frontal cortex (Ingvar 1974). The brain during any resting period is actually quite vigorous, where without any stimulation the mind freely wanders through past recollections, envisioning future plans, and other thoughts and experiences (Andreasen et. al. 1995, Buckner & Carroll 2007). This phenomenon was termed the ‘default network’ to describe the brain activity at rest (Gusnard et. al. 2001, Gusnard & Raichle 2001). The significance of the ‘default network’ to creativity is that continued underlying processes still occur that are unrelated to conscious thought occur, something described in the incubation process mode of the creativity process (Buckner et. al. 2008). Research has shown that mindfulness can activate the ‘default network’ (Jang et. al. 2011). The ‘default network’ deactivates is active when an individual is at rest and shuts down when an individual becomes active and is focused on the outside world.

The Creative Insight

When a sub-conscious connection between two bits of information fit a problem, a realization that brings a feeling of insight occurs. This illumination is often described as the ‘aha’ or the ‘eureka’ moment. This insight may not bring the whole solution of the problem but perhaps provide a key piece of information that enables the problem to be restructured, reorganized, reframed, reconstructed or reconsidered in some now light, where a solution comes forward with relative ease.