Defence mechanisms evolved thousands of years ago to protect humankind from the dangers of the environment. They originate from man’s need to hunt, protect, nurture and generally survive on the Earth (Tiger & Fox 1972). When man faced danger, he had two basic choices open to him; fight or flight. This primal defence mechanism is ready to be activated only after a number of very quick physiological changes in the body creating stress and anxiety occur, so the person can make the decision to defend himself or flee from the scene[1].

Living today in a modern society creates stress and anxiety that is sustained in the person much longer than the ‘hunter’ who only dealt with short skirmishes. Anxiety is a primal response to danger and in modern society it builds up in us, something akin to us making regular deposits of money into our savings account. Stress manifests itself with a number of symptoms like high blood pressure, digestional problems and insomnia, which can lead to the danger of blood clots, stroke and heart attack. These are now the highest causes of death in both middle and high income countries (WHO 2004). The effect of stress and anxiety is to hinder concentration, restricting thinking to only immediate problems, without consideration of the long term consequences (De Board 1978, P. 113). Stress and anxiety also leads to a number of behavioral responses which are based on a defence mechanism.

Anxiety today is not externally produced as it was for the hunters. Anxiety comes from within, manifesting subjective dangers with corresponding feelings and emotions over longer periods of time than the hunters. This anxiety is neurotic rather than objectively caused anxiety originating externally. The approaches the psych takes to managing anxiety have also evolved in sophistication over thousands of years and form an important part of our personalities.

Human Personality has a strong influence on every aspect of life. A person continually experiences objects, people and events that create pain, suffering or pleasure, happiness or sadness, with other emotions, that largely go unnoticed during the day (De Board 1978, P. 25). Emotions create various human feelings may originate from either external events, i.e., threats to physical safety, a feeling of pain or pleasure, i.e., rapid sexual arousal, or to a moral issue, i.e., some feeling of guilt (Larsen & Buss, 2005, P. 284). These emotions and feelings can distort perception, where external and internal stimuli become confused and often exaggerated, sometime leading to psychotic behaviors[2], discussed previously. Our psych acts to control and stabilize these emotions so a person can cope with everyday life through a number of defence mechanisms.

Defence mechanisms are psychological strategies that the psych develops to cope with the emotions generated through everyday life (Larsen 2000). They try to preserve a person’s self-image and view of the world. Normality often contains neurotic traits which can be triggered by anxiety and dominate one’s perception over a period of high emotion. In such situations, defence mechanisms can over compensate and develop distortions and misperceptions, preventing productive behavior, making things worse (Cramer 2000). Defence mechanisms used in their extreme take away both psych and physical energy from other tasks which weaken a person, pushing him/her into some degree of psychosis. They can cloud perception and thinking and affect the way problems are seen and approached (Larsen & Buss, 2005, P. 292).

Defence mechanisms can be considered as a group of personality traits that originate in the psych[3] and function to protect a person’s self image and assumptions, values and beliefs that make up his/her view of the world. They act to reduce anxiety, fear, stress and guilt. They defend a person from the painful realizations that will challenge one’s identity. They reduce the inconsistencies between one’s view of self and world and any external evidence that would refute that view. They simplify the complexities of situations that contradict a person’s simple view of reality. Defence mechanisms reduce fear and build security so that a person can live with the dangers and threats in the world.

Therefore defence mechanisms have some influence upon the construction of opportunity, which itself is a desire of a certain reality. Defence mechanisms can obstruct one seeing opportunity and inhibit action out of the fear of uncertainty new opportunities can potentially bring. Defence mechanisms have something to do with how we reconcile the paradox of an opportunity bringing potential success and also the potential fear and uncertainty of failure that goes along with it.

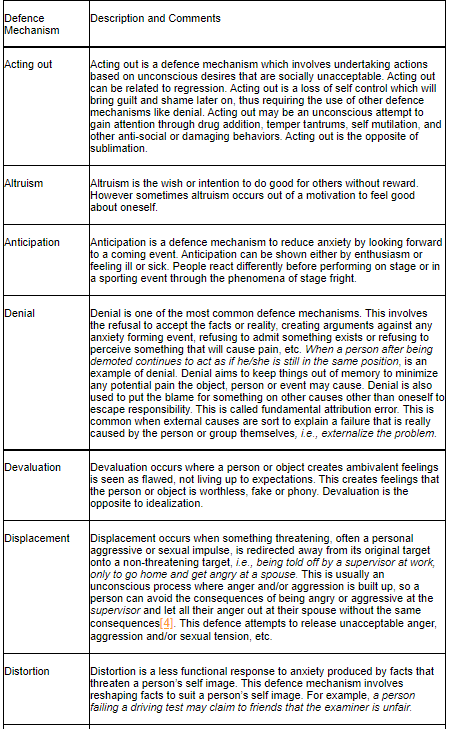

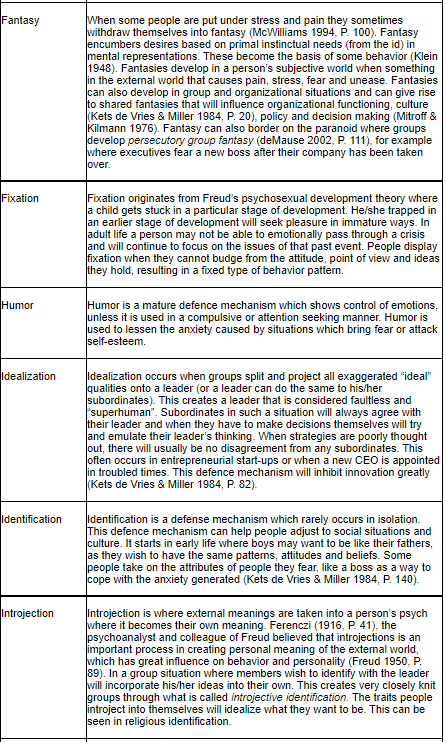

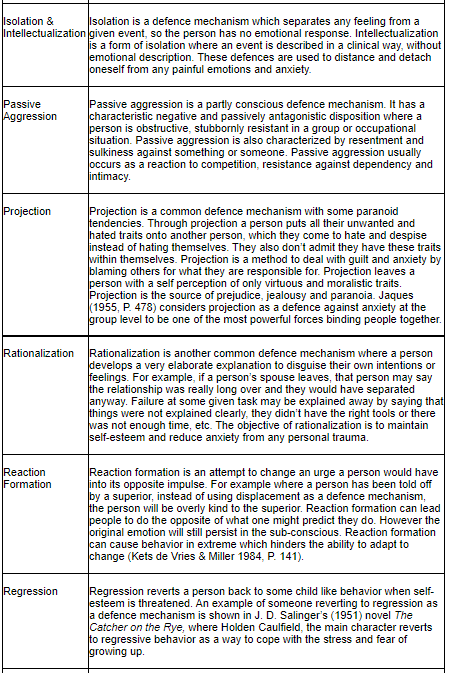

Defence mechanisms can be classified into four levels (Valliant 1977). The first level defences can be considered psychotic where external experiences are distorted in some way to cope with reality. These include denial, distortion and delusional projection, all common in psychotic disorders. The second level defences are immature defenses. They are common in childhood and carry their way through to adulthood in many people. These defenses inhibit a person ability to cope socially and effectively reduce any anxiety. They are common in depressive disorders. These include fantasy, projection, passive aggression, acting out and idealization. Level three defences are neurotic, fairly common in the adult population. These types of defences can destabilize relationships general life. They include displacement, isolation, intellectualization, reaction formation, repression, regression and rationalization. Level four defences are the most common and include altruism, anticipation, humor, identification, introjections, sublimation and suppression. These defence mechanisms are developed by individuals throughout their life and become very unique to a person’s personality. A person using these defences would usually remain productive, being able to control and use his/her emotions to their benefit.

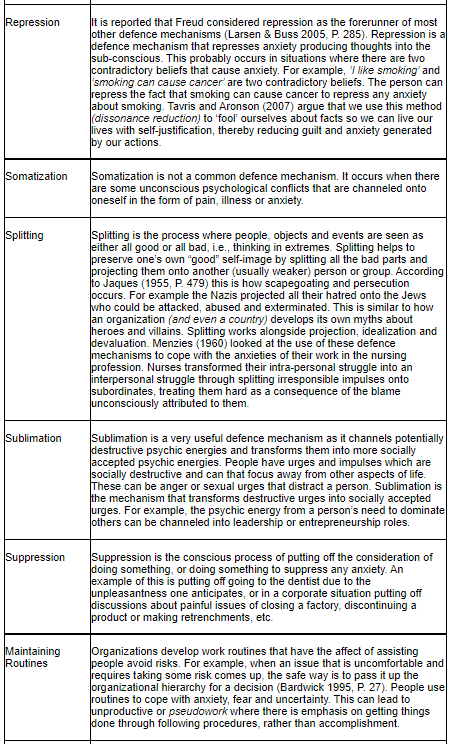

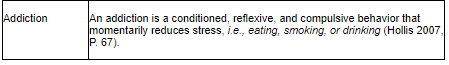

There are numerous more defences that the psych develops against anxiety (A. Freud 1936). Some of the major ones mentioned above are listed in the table below.

Common Defence Mechanisms

Published in Ovi Magazine 28th December 2012

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

Notes

[1] When a person is exposed to some sort of external danger arteries near the skin begin to clamp down, muscles begin to tense and blood pressure rapidly rises. The heart begins beating at a rapid rate and blood is redistributed to the limbs, ready for any quick moves. Bowels release to reduce weight and adrenalin is pumped into the blood stream to help the blood clot quickly if any injury occurs.

[2] This is the basis of psychoanalytical theory. Psychoanalysis looks at the whole personality, rather than individual traits, and behavior. Psychoanalytical theories consider object-relations which begin with a person’s relationship with a mother’s breast and develop throughout childhood, and ones basic instinctual needs as the major factors influencing the development of personality. A child develops a world of pleasure and pain, hate and love, where he/she forms their own self view and view of the world. This development continues through life and these mental representations become the way that a person perceives, interprets and constructs their own meaning of the world. A person’s instinctual base develops into a continuum of needs and wants, which becomes fantasized into unconscious schema, creating a subjective world in a person where potential urges and behavior originates. We are interested in this from the point of view as how a person perceives the environment, develops ambitions, sets objectives, develops strategy and reacts to potential opportunities.

[3] According to Freudian psychology defence mechanisms originate from the ego. The need for defence mechanisms occurs when the id (a primal, instinctual pleasure orientated part of the personality that is impulsive) comes in conflict with the super-ego (the social morality aspect of the personality). Un-satisfaction, desire, anxiousness and/or fear will eventually rise to the consciousness and needs to be suppressed by the ego through defence mechanisms to block the id.

[4] However this may create other long term relationship problems with the spouse.

***********************************************************************************

References

Bardwick. J. M. (1995). Danger in the Comfort Zone: From the Boardroom to the Mailroom – How to Break the Entitlement Habit That’s Killing American business, New York, American Management Association.

Cramer, P. (2000). Defense Mechanisms in Psychology Today: Further Processes for Adaptation, American Psychologist, Vol. 55, pp. 637-646.

De Board, R. (1978). The Psychoanalysis of Organizations: A Psychoanalytical Approach to Behavior in Groups and Organizations, London, Tavistock Publications.

De Mause, L. (2002). The Emotional Life of nations, New York, Karnac.

Ferenczi, S. (1916). Contributions to Psychoanalysis, Boston, Richard Badger.

Freud, A. (1936). The Ego and Mechanisms of Defense, London, Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Freud, S. (1950). Totem and Taboo, London, Ark Edition (1983).

Hollis, J. (2007). Why Good People Do Bad Things: Understanding our darker selves, New York, Gotham.

Jaques, E. (1955). Social Systems as a Defence Against Persecutory and Depressive Anxiety, In Klein, M., Heimann, P. and Money-Kyrle, R., (Eds.), New Directions in Psychoanalysis, London, Tavistock Publications.

Kets de Vries, F. R. and Miller, D. (1984). The Neurotic Organisation, Diagnosing and Changing Counterproductive Styles of Management, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Klein, M. (1948). Contributions to Psychoanalysis 1921-45, London, Hogarth Press.

Larsen, R. J. (2000). Toward a Science of Mood Regulation, Psychological Inquiry, Vol. 11, pp. 129-141.

Larsen, R. J. and Buss, D. M. (2005). Personality Psychology, 2nd Ed., New York, McGraw-Hill.

McWilliams, N. (1994). Psychoanalytic diagnosis: Understanding personality structure in the clinical process, New York, Guilford Press.

Menzies, I. E. P. (1960). A case-Study in the functioning of Social Systems as a Defence Against Anxiety: A Report on a Study of the Nursing Service of a General Hospital, Human Relations, Vol. 13, pp. 95-121.

Mitroff, I. I. and Kilmann, R. H. (1976). Organization Stories: An Approach to the Design and Analysis of Organizations Through Myths and Stories, In: Kilmaan, R. H., Pondy, L. R. and Slevin, D. P. (Eds.), The Management of Organization Design Strategies and Implementation, New York, Elsevier/North Holland.

Salinger, J. D. (1951). The Catcher on the Rye, Boston, Little, Brown & Co.

Tarvis, C. and Aronson, E., (2007). Mistakes Were Made (but not by me): Why We Justify Our Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions and Harmful Acts, London, Pinter and Martin.

Tiger, L. and Fox, R. (1971). The Imperial Animal, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Valliant, G. E. (1977). Adaptation to Life, Boston, Little, Brown & Co.

World Health Organization (2004). The Top Ten causes of Death, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.html, (accessed 5th November 2009).

The symptoms described particularly affect empathetic people who are now by default living in a psychopathic environment (pathocracy). The cure is to live in a natural and loving environment then the mental health issues disappear. Psychopaths (aka sociopaths) on the other hand thrive in this environment and aren’t much inhibited or limited by it. They don’t suffer those effects generally because they lack emotion. Their issues come instead from a lack of control, a lack of victims to play with (torture) or exposure that casts them into a bad light (the truth) in front of empaths.