Developing natural products and new value chains in Kelantan while maintaining cultural integrity: What, How and For Whom?

Part 2

New Natural Product (Essential Oil) Characteristics

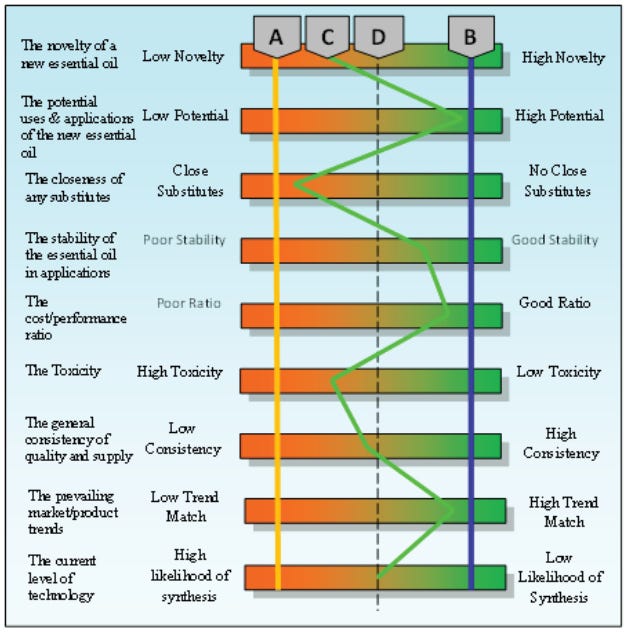

The market potential of a new natural product (in this case: an essential oil) depends upon the potential range of applications within the flavour and fragrance, cosmetic, aromatherapy, or agricultural chemical industries. The scope of potential uses directly corresponds with the characteristic strengths and weaknesses of the oil. The major criteria are summarized below;

The novelty of the essential oil is determined by the perceptions of the intended industry, i.e., onganoleptic or olfactory profiles for flavour and fragrances, folklore and fact for aromatherapy, or efficacy for cosmetic or agricultural applications. The degree of novelty is limited by the closeness of substitutes.

The potential uses and applications of the new essential oil. These have to be accepted by those within respective industries.

The closeness of any substitutes. The closer any potential substitutes the less the potential.

The stability of the new essential oil. The essential oil must be stable in potential applications.

The cost/performance ratio. The new essential oil must perform cost effectively in potential applications to be of interest to industry.

Toxicity is a major issue in the international trade of essential oils, particularly to the EU markets. This may take a lot of time and expense to develop a dossier to prove product safety.

The general consistency of quality and supply. Any new essential oil must have enough production volume for major potential customers to take the product seriously.

The prevailing market/product trends. New essential oils that match current market trends will be more acceptable than those that don’t.

The current level of technology. The more difficult it is to reconstitute a new essential oil in a laboratory, the greater the market potential (Hunter 2009, pp. 245-246).

Figure 3 shows a grid with each of the above product characteristics plotted vertically where a determination about each characteristic can be made and plotted. Line A shows an essential oil with low novelty, and low potential applications, etc. This would not be very viable. In contrast line B is highly novel and high potential applications, etc., and is highly viable. However most new essential oils will not have uniform viability across all the characteristics like line C and require great examination about what characteristics are most important to the potential market sector. Line D shows a new essential oil that has very little advantages and thus of marginal industry value.

Figure 3. A Grid showing the characteristics of a new essential oil.

The Agronomic Characteristics

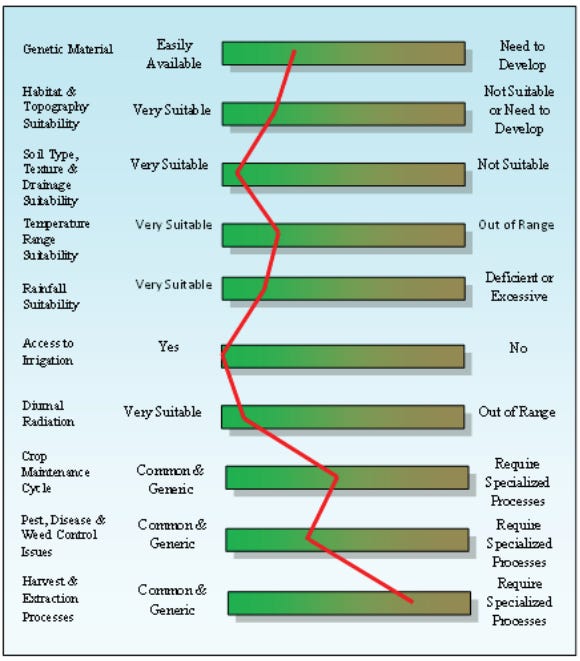

The second area of evaluation is straight forward agronomic evaluation. These include the availability of the correct genetic material, the habitat and topography of the selected land site, soil type, texture and drainage, temperature range suitability, rainfall suitability, access to irrigation, diurnal radiation, the complexity of the crop maintenance cycle, pest, disease and weed issues, and the complexity of harvest and extraction. Very few crops have exact matches with the land they are planted upon, but the grid shown in figure 4 lays out the issues visually so the required conditions for the new essential oil can be evaluated according to the proposed land site.

Figure 4. The Agronomic Characteristics Required for the New Essential Oil

The Project Characteristics

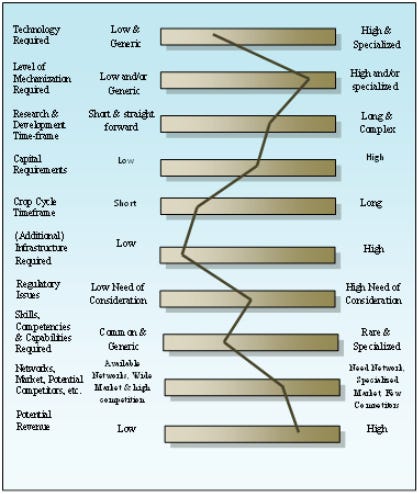

The final area of evaluation is primarily specific project issues that will vary according to the entrepreneur, enterprise, and location. Is the technology required for the venture low and generic or high and specialized? Different entrepreneurs will have different access to technologies and thus make different evaluations. Likewise the level of mechanization will depend both upon the type of crop and planned farm size. Different crops will have different research time frames ranging from simple trials to long drawn out formal research projects in conjunction with outside research institutions. Capital requirements will be unique to the type of crop, and depend partly on existing farm infrastructure to some degree. It will be much more costly for an entrepreneur to enter the industry as a new player than expand production from an existing base. Crop cycle timeframes will vary according to the specific crop and different entrepreneurs have different views about what they are looking for and prefer. How much additional infrastructure is needed is a prime determinant of viability and will differ greatly among farmers.

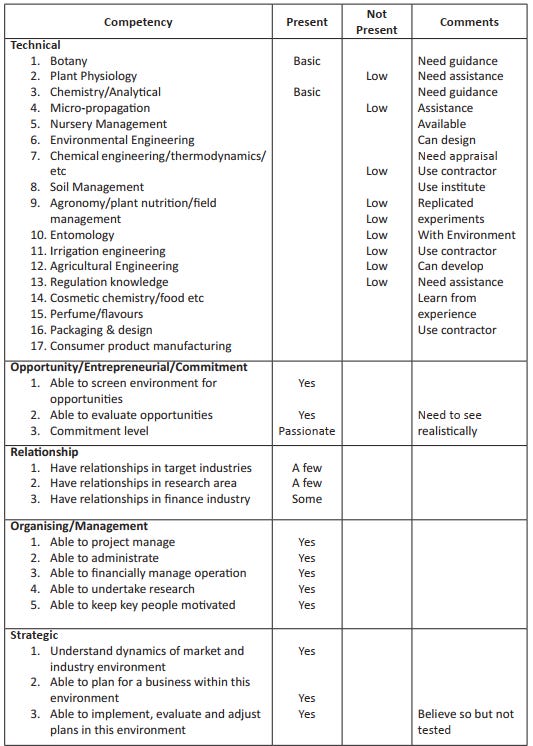

The last three criteria are extremely important. Regulation of essential oils has become so stringent of late. It is very important to spend a lot of time examining what is required in this area thoroughly. It is not just about meeting the cosmetic, pharmaceutical, or food law requirements here at home and abroad, but also about GAP, OSHA, and EPA, etc. The current level of skills, competencies, and capabilities is paramount to viability and success (see table 3). In most cases specific skills for specialized essential oils will be low, although basic agronomy knowledge may be good. The critical issue here is whether you believe and are prepared to travel along the steep learning curve needed to develop a new essential oil crop. Is this a challenge you want to accept, or something that makes you put the whole idea in the ‘too hard basket’? Finally, do you have the networking necessary to develop and market the crop? Where and what is the actual market you are planning to enter? How big is this potential market? And, Are there competitors or potential competitors around? Figure 5 shows the specific project criteria that need to be evaluated for viability.

This short sojourn into examining new essential oil viability covers the basic issues in a pictorial way that will quickly highlight the issues and challenges requiring much greater thought. Each new natural product and project is unique and consequently will have it’s own unique challenges.

Figure 5. The Project Characteristics.

Table 3. A Simple Competency Audit Example (Hunter 2009, P. 299).

Most industries prefer plant extracts that have full documentation and a history of use known to consumers exists[8]. This requires pharmacopoeia, scientific dossier, and scientific journal results that are accepted by regulatory authorities[9]. To meet many of these requirements, the outsourcing of extraction and processing according to international standards is required. Therefore, developing this basic infrastructure around strategic locations of the state is necessary. SMEs must then decide whether they will specialize in the production of the crude material or incorporate that material into a consumer or industrial product, and this is where the development of the supply/value chain must take on major consideration.

Value Chain Development

Natural product development fits into the traditional discipline of new crops, a field of agriculture which looks at the potential introduction of new species or varieties being placed in new locations, with new technologies for producing a product, with a new market, or a combination of all these factors. Thus, for a new natural product production venture to be successful, the application of new breeding techniques, efficient production systems, development of new products and markets are all required. In the majority of cases, the knowledge to achieve all the above is strange and unknown to the new producer. On the sales side, new customers, whatever position they are in the supply chain, need to be satisfied in terms of product, price, quality and service level. This product must be produced competitively enough to cover propagation, growing, crop maintenance, harvesting, processing, marketing and administrative costs, as well as allowing for enough profit margin for each member in the value chain.

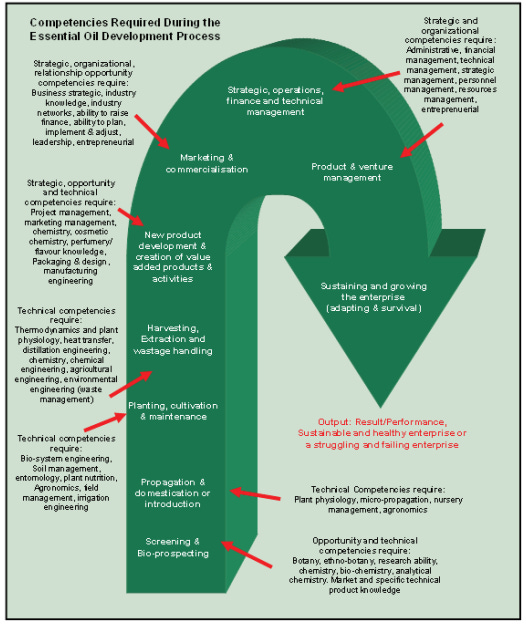

Developing and managing a successful natural product venture requires understanding the technical disciplines of botany, natural product chemistry, plant physiology, propagation methods, agronomy, agricultural and extraction engineering, and analytical chemistry, as figure 6 depicts. Many technical problems require solutions that can be only partly solved through individual disciplines, thus requiring an interdisciplinary approach. In addition, farm to consumer supply chain knowledge, planning and market development is necessary. Both areas of knowledge and expertise must be developed in tandem to create a venture that is successful. Ignoring either side of the new venture development, will most likely lead to failure.

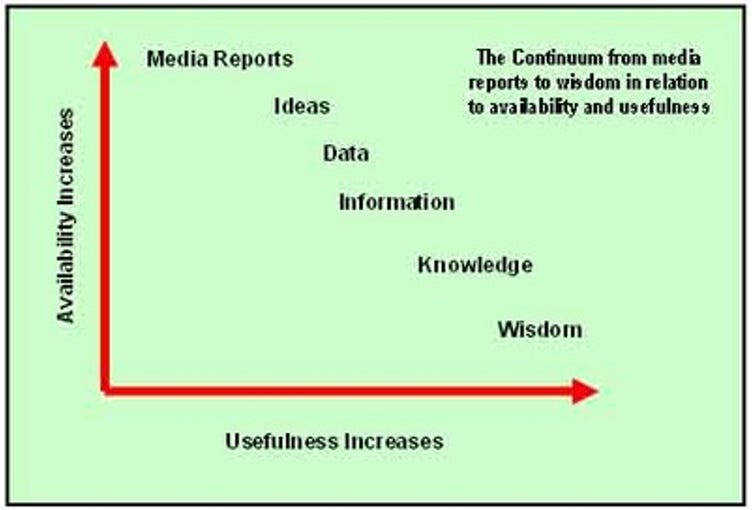

In many cases, those setting out to develop a new natural based product venture will usually have little previous farming, processing and/or market experience. This immediately sets out a number of challenges. Firstly the degree of success will be directly related to what crop is chosen. Selecting the right crop to grow (and this also has much subjectivity), will depend upon the access to good information which can lead to the making of informed decisions. Usually the first exposure to knowledge is news passed on from a friend, conference or seminar or some form of media, electronic or otherwise. There is no shortage of media reports and internet information about natural products, which can lead to ideas. However one must be extremely cautious as most media reports, internet information and even many conference and seminar papers which are sometimes developed for publicity purposes and can be full of ‘hype‘ and enthusiasm, rather than factual information and knowledge. Technical and scientific papers although often of great use in technical development, however they are not marketing documents The potential producer needs to be aware of the limitations of published information.

The above sources of information can lead to no shortage of ideas, which sometimes carry emotive wishes. These ideas must be filtered through the use of more factual information to screen the facts from the ‘hype‘. Decisions need to be made on the best factual information available, which can lead to accurate knowledge. This can only be achieved through discussions with potential customers and trial and error in field trials, so knowledge can be developed into the wisdom needed to develop a successful enterprise. Figure 7. shows the hierarchy of information that one has access to aid the essential oil development process. This process must eliminate wishful thinking and excitement to convert mindful enquiry into a more rational and objective frame to be able to observe the realities of technical and market issues, before proceeding to the next stage.

Figure 6. Disciplines Required in the Essential Oil Development Process

Figure 7. The continuum from media reports to wisdom in relation to availability and usefulness.

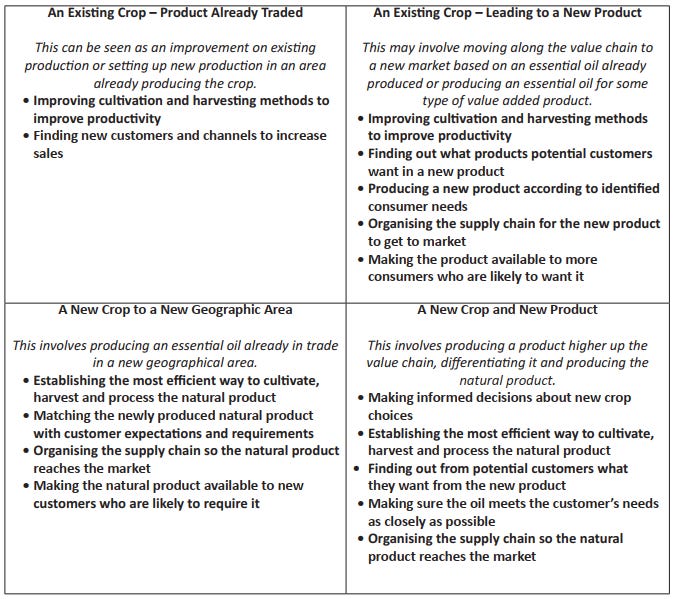

Strategy development must also take into account the interest of the promoter and accommodate his or her vision. This interest may be generated from thoughts and feelings about the industry, products and markets, originating from a desire to vertically integrate into agricultural production, an interest in a specific natural, a wish to develop products from a specific or group of natural products or a desire to find an alternative crop. Whatever the inspiration for the promoter’s vision is, it will most likely fit into the natural product Strategic Matrix shown in Table 4. This matrix identifies the basic characteristics of the contemplated natural product as 1) an existing crop – product already traded, 2) an existing crop – leading to a new product, 3) a new crop to a new geographical area, where the product is already traded, and 4) a new crop and new product. Shown in the table below are the specific important issues (or desired outcomes) that will become important objectives of the development project.

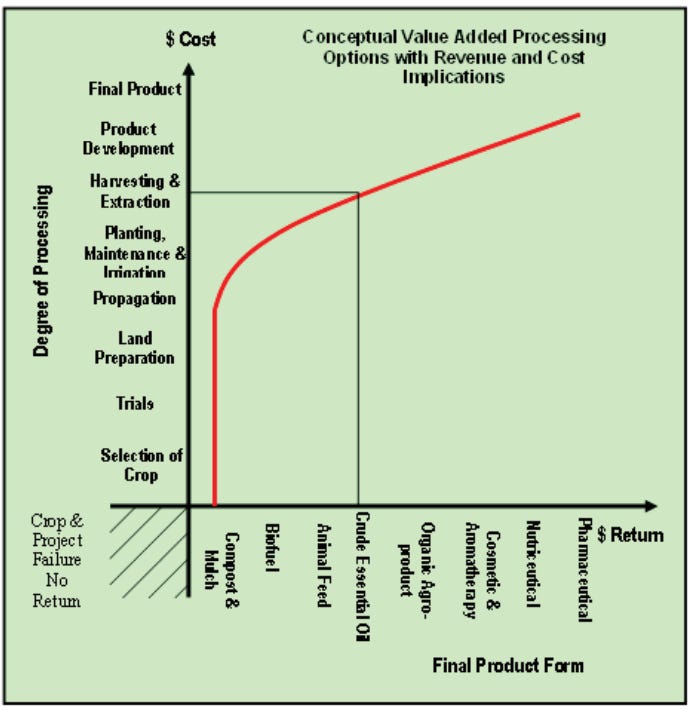

The promoter’s vision may involve a want to produce value added products based on the crude material as an input into a final product, or utilising parts of the plant material for the production of other by-products, or utilising waste materials as much as possible to improve revenues and sustainability. In these cases the venture may market various products to different industries (i.e., agro-products, alternative energy feed-stocks, animal feed, etc.), or in the case of value added essential oil products, focus on higher parts of the supply chain. These visions heavily influence the whole focus, capital, technology and processing, management and market development requirements of the venture. These value-added and by-product diversifications also affect revenue. Figure 8. conceptually depicts the various value-added processing options with cost and revenue implications.

Table 4. The Natural Product Strategic Matrix

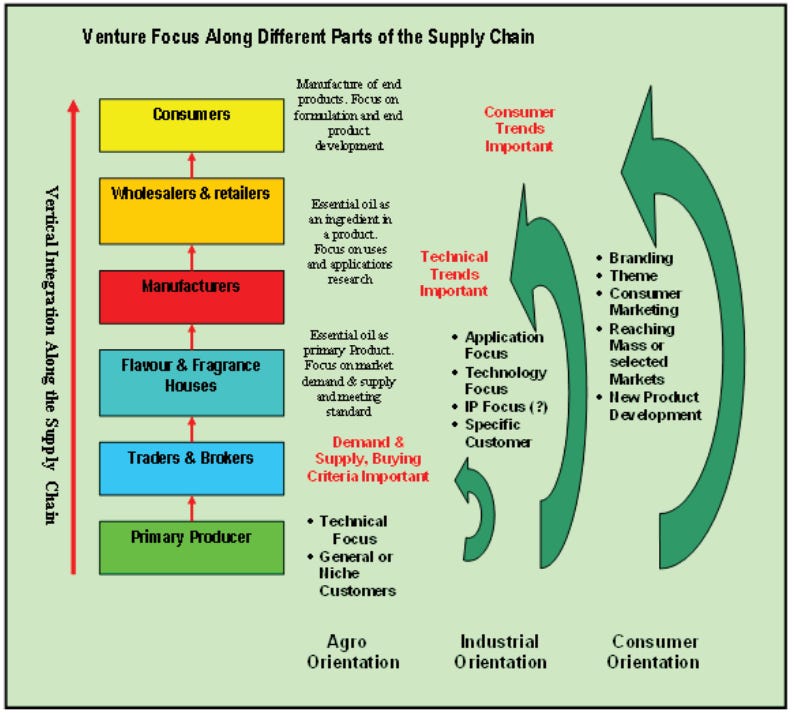

After considering what type of product could be produced by the potential venture, which part of the supply chain will be focused upon to generate sales will be the next issue. The type of product and level of the supply chain the enterprise targets will require focus on different sets of issues. The production of an essential oil for the flavour and fragrance industry, especially an existing item of trade will require studies and information about current World demand and supply, future expectations, trends and the elasticity of supply from current producers. Once satisfied there is room for a new producer, the enterprise can target specific customers to work with or attempt to develop selling channels through traders on the open market. The development phase will be mostly concerned with technical aspects of producing the natural product, which include meeting regulatory requirements, producing the desired olfactory profile required by customers, and meeting a cost that provides a positive return to the producer. This enterprise has an agro-orientation, where the important issues are demand, supply, competitive costs and quality.

Figure 8. Conceptual Value-Added Processing Options with Revenue and Cost Implications

Producing a new natural product will require focus upon potential specific industry applications that the oil will attempt to satisfy, whether it is for a flavour, fragrance or cosmetic ingredient, etc. Knowledge about final application of the oil in the intended industry use is important, so its potential value can be demonstrated. Some development of intellectual property, whether through patent or proprietary knowledge on process or product is likely, and can be used as a method to create barriers of entry to other potential producers. Within this focus, close work will most likely be undertaken with specific customers who may or may not exclusively purchase the product from the producer in the future. This type of enterprise has an industrial orientation, where the important issues are technical development, potential substitutes and complementary products.

Producing one or a number of natural products as intermediate products in the production of end products, such as aromatherapy, cosmetic, agro-chemicals, nutraceuticals or pharmaceuticals requires a focus upon the market. This means understanding consumer tastes, trends, product development and how to engage consumer markets. The enterprise is required to develop products that match and fulfil consumer wants, building up a theme or corporate and product brand images that differentiate the product from others already in the market. The enterprise will be concerned with ways to make the message about their products reach as many consumers as possible within the groups they target. Over the last decade new methods like the internet and direct marketing channels in South-East Asia have become very popular and allowed a number of companies to utilise these alternative supply chains, as has been successfully undertaken by Thursday Plantation Tea Tree Oil in Northern New South Wales, Australia. This type of enterprise takes a consumer orientation, where emerging consumer trends, new product development and channels of distribution are their important issues. Figure 9. shows the various differences in venture focus along different parts of the supply chain.

Figure 9. Venture Focus along Different Parts of the Supply Chain.

The final consideration within the vision development for the potential project is the type of production structure, organisation and entry strategy. The structure and organisation will depend upon many factors. For example, issues like who are intended as the beneficiaries of the initiative, the selected crop, location, market size and potential market share target, required level of field and extraction technology and envisaged scale of the enterprise, will influence structure and oranisation. A number of options exist, which include a) wild collection, especially if the crop cannot be cultivated like sandalwood within a short to medium time frame, b) small scale production similar to a small holder if the project is a hobby, c) an extension crop of an existing farming enterprise, d) a small to medium sized plantation or e) a large plantation, if economies of scale are needed to develop the market based on cost competitiveness. These types of enterprises can be controlled and managed by an individual, family or company, a cooperative or community group, or a company controlling processing facilities and a marketing organisation.

The Basis of Action

So what are the specific problems that must be overcome to develop new natural product based enterprises in Kelantan? These problems will include;

Lack of capital for production development.

Lack of capital for developing the market and creating new channels,

The difficulty in taking advantage of channels of distribution once they have been created, gained, or developed,

Small local market,

The difficulty in developing new natural product based entrepreneurs,

The difficulty in creating enough product differentiation to really make a difference in the market,

Overcoming producer isolation,

Incubating multiple “farm to consumer” projects at once, and

Difficulty in getting larger companies to commit, invest, and distribute products produced at village level.

Solving the above problems requires a carefully thought out plan that takes into account the local conditions in Kelantan, involving a number of steps.

Determine Kelantan’s Branding Advantages which involves developing a branding story and market philosophy that has horizontal and parallel diversification potential. This could be based on the development of the Toyyib/Halal herbal concept, organic, and ethically based community framework that will appeal to consumers outside of Kelantan and within the Asian region. For example herbal treatments based upon an Islamic theme would be able to exploit local biodiversity, utilize the local culture as part of the branding theme, maximize the benefit of location of “Brand Kelantan” as a marketing advantage which will create a new source of competitive advantage through differentiation into a relatively low competitive market segment. This branding exercise would reverse all the disadvantages of production fragmentation, remoteness and location into a strength – products produced by the community that benefit the community directly – the essence of Fairtrade and ethical products.

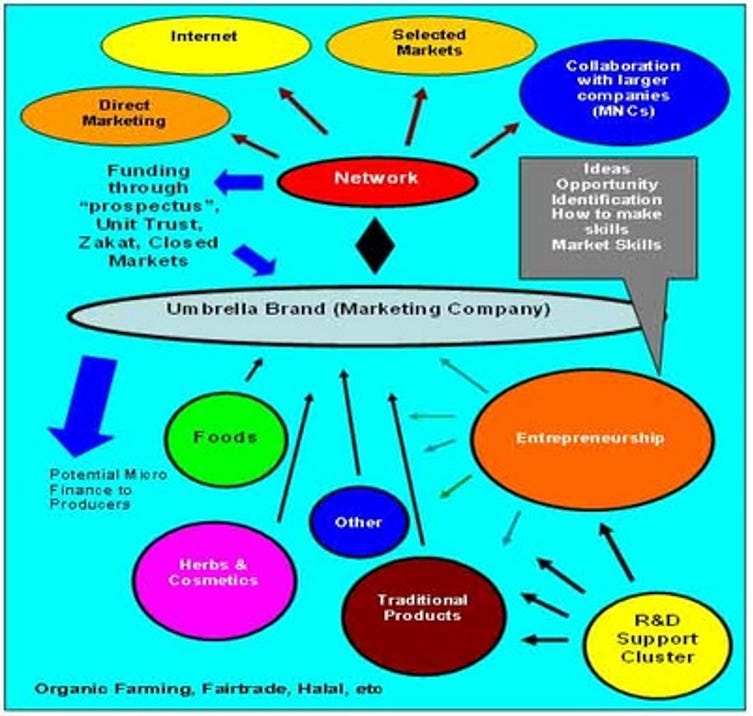

Centralize the marketing and decentralize the production and ownership. Create an enterprise that centralizes the product development, marketing, sales, finance, and general operations and decentralizes the production to members of the alliance or cooperative. This marketing organization would be responsible for developing the business and responsible to the membership, who are the producers. The centralized enterprise would coordinate research with local research institutions, operate as a direct marketing company, promoting products through multiple channels like roadshows, airlines, airport terminals, shopping malls, and through online website shops[10]. The firm would also possibly through a unit trust arrangement be able to raise capital from the public. The marketing company could be operated by graduates of University Malaysia Kelantan, under supervision of marketing professors – the younger generation working hand in hand with the older generation. Figure 10 depicts the business model described above.

It must be strongly emphasized here that a small group of people will have to take the responsibility the potential crops, products, and value chains that need developing and take the initiative of educating and disseminating information among the kampong people, and in return receive a natural collaborative effort and participation from them. There is also the risk and tendency of duplicating and copying any successful product by others that may create a glut and oversupply of a particular product[11].

A producing company would be a democratic co-operative, of local producers, workers and collectors, mentored by professionals. The venture, will have ethical trade at its heart, working in partnerships with producers to first meet their nutritional, food and health needs, including local communities, have long term arrangements with the marketing company, and will act as a resource base for its producers/partners, fully supporting them in providing them with required services at their doorstep, leaving them to farm and on farm responsibilities. The aim is to provide a smooth, transparent, and fully managed supply chain, from primary production, knowledge, management, adding value, holding capacity and ensure the ‘Cash to Cash Cycle’. The company would act according to the following principals;

1. Commitment to Social Justice in Organic Agriculture

2. Transparency and Accountability

3. Direct and long-term trade relationships built on trust and mutual respect.

4. Equitable distribution of returns to stakeholders

5. Communication and information flow

6. Skills development and capacity building

7. Internal ethics, and

8. Professionals manning the PC, support the local community[12].

Figure 10. The “Brand Kelantan” Business Model (Modified from Hunter 2008).

The cooperative would be committed to organic, integrated and sustainable production. The cooperative would be involved either in agriculture or in both agriculture and product manufacturing as part of the overall marketing strategy of the marketing company.

Finance for the cooperative will come partly from the marketing company which will channel funds according to the cooperatives designated projects.

The producing companies aim is to develop a share holding structure that is beneficial to all parties involved. It is hoped that key producers will become shareholders in the company, thereby becoming ‘producer partners’. Although PC will also engage in one-off trades with producers considered ‘non-partners’, the above benefits, and the option to become ‘shareholders’ and therefore receive a yearly ‘bonus’.

Three types of shares are envisaged:

The Founder’s shares, which would be the majority initially

Shares bought by large investors (which will not be sought initially)

Shares held by producers, who would not invest other than with their

products and favourable pricing.

A central marketing company could exist for each market. The objective of the central marketing company would be to develop and control the market in each country and organize producers according to the needs of the market. The company would primarily be involved in product development in association with a university, organizing logistics from producers to the market, providing finance to producer units and undertaking the national marketing.

The management of the company would be by a small group of professionals, preferably post graduate students under mentorship. The organization would aspire to be a knowledge based company, which would compile and disseminate information to those groups that require it for smooth operations. The specific groups within the company would include;

Strategic group

Management group

Marketing group

Product development group

Extension group

Resource sourcing group

Direct Marketing (sales group)

Access to local decentralized facilities. Remote regions in Kelantan like Jeli and Gua Musang will require common facilities that would be available to entrepreneurs in the area. Such facilities would drastically lower the barriers to entry into the natural product processing industry and solve issues like the requirement of GMP and HACCP compliance. Where a cluster of growers exist, common facilities will improve the viability of these enterprises. These are issues that the ECER authorities and Kelantan Biotechnology Corporation could consider.

Most, if not all pieces of processing equipment can be locally fabricated. In fact, distillation equipment for farmers in Australia, Indonesia, India, and Cambodia, etc., are in the most part fabricated from scrap found and procured locally and built relatively cheaply with the right knowhow. Alternative methods of extraction such as solar distillation can be home-built very cheaply and suit small holders with small quantities of biomass to distil, eliminating all fuel costs at the same time[13]. Small manual “Kubota” type farming equipment can be modified to assist with harvesting. Organic fertilizers can be produced within cooperatives where the “gotong royong” approach to production is taken, with each member taking home their share according to their efforts.

Rapid advances in technology are driving economic growth and development throughout the world. Technology advances were the catalyst of the industrial revolution. The advances in information, communications, containerization and transport technologies over the last few decades have provided the means for businesses to operate on a global scale like never before. However, technology in much of the developing world is adopted without question. Dr. Asma warns there …“is also the tendency for Asian countries, including Malaysia, to deal with the issue of values in development by importing many technologies and systems wholesale from abroad without going through the process of mental transformation necessary to master them fully. Although Malaysia is going through rapid transformation, our growth is one without development in the context of knowledge contribution to science, engineering and technology. As long as we are consumers and operators of sophisticated techniques, plants and technologies imported wholesale from abroad, we are to a certain extent undergoing a technology-less form of industrialization. This transformation of values and attitudes is a key issue in the nation’s development agenda” (Asma 1995). Blind acceptance of technology is a barrier to empowerment, reinforcing the accepted market structure. Accepting technology as a given, is associated with a paradigm of doom, inhibiting local innovation.

Processing factories with GMP status can be built within mobile shipping containers and be moved from region to region as needed for processing and manufacturing. Professor Howard Frederick of Deakin University pioneered this system building a chocolate factory in New Zealand which was transported to Melbourne Australia for production. The key to success is finding and developing appropriate technology for what is required.

The role of local universities. Local universities will need to play a very important role as part of their outreach obligation to the community. This role would be wide and varied beginning in the field of local and situational research of potential new crops and rural industries for Kelantan. As mentioned earlier, Kelantan requires a localized rather than follow the national research agenda that organizations like MARDI are obligated to pursue. This may mean uncoupling research from the national agenda to focus on local needs and priorities. Therefore, local universities need to fill the research gap that exists in Malaysia.

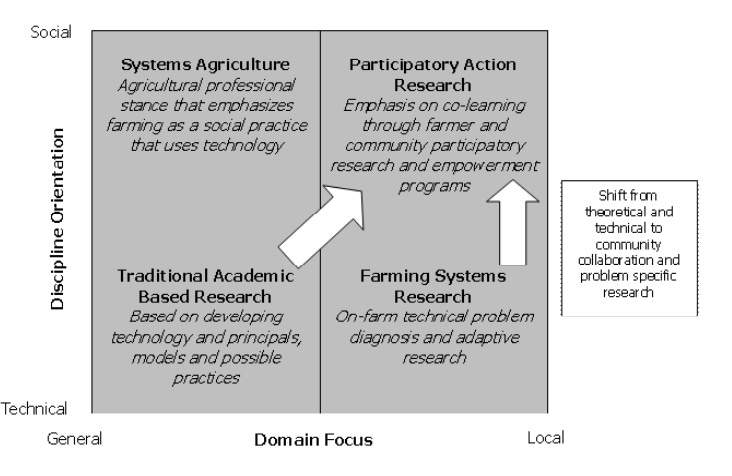

Future essential oil research cannot rely on public research funding to assist in the establishment of new essential oils. Farmers will need to empower themselves and lead their own research in what is called farmer driven research (Biggs 1995). This research approach escapes the irrelevant research provided by public institutions and focuses on the real needs in developing a new crop (Martin & Sherington 1997). Many research models involve the farmer in their own crop trials, without the same rigour as academic research to achieve useable data that can be utilised by farming communities. This approach is called participatory action research, farmer participatory research, participatory technology development and on-farm research. Although these models were originally developed for Third World farming communities, they are quickly being adapted to problems of farming in developed countries (Dillon & Virmani 1985). The shift from traditional based research to participatory action research is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. A typology of Various Farming Research Management Concepts

The university will also need to play a role in providing specialized entrepreneurship programs for bio-entrepreneurship. These courses will be much more specialized than standard entrepreneurship courses provided to rural people through various agencies. Mentorship to members of the umbrella marketing company will also be important where marketing and entrepreneurship professors will need to advise and guide graduate executives of the company.

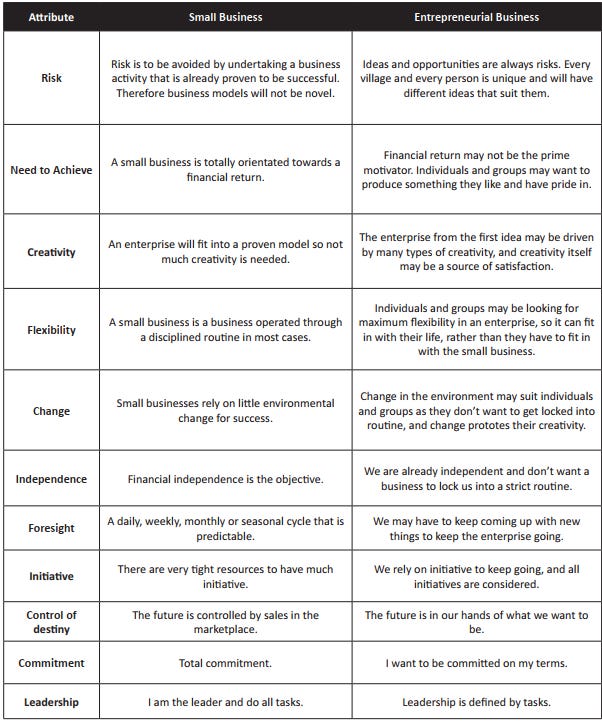

There are few programs available to rural people at or near their domicile. Institutions set up specifically for community education most often lack instructors with business experience at the micro level. Those courses available are mostly based on conventional small business courses that are totally inadequate as they fail to empower participants in the creativity of ideas, and focus on business models, which already exist in heavy competition. They don’t show how to seek resources outside of traditional institutions and lack guidance in showing how to seek innovative ways to apply useful technology to the circumstances of how and where they live. The gap between what is available, and what is needed, can be seen when contrasting the various tenants of the small business and entrepreneurial paradigms as shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Small business and entrepreneurial paradigms (Hunter 2008)

Resource gathering needs revolution to enable empowerment. The current systems of finance available depend upon conventional business plans, collateral and experience. People have little knowledge of where to get grants and little ability to apply for them. Existing national grant schemes often make it so hard to get, many feel it is wasting time trying. So much government development money is going to development projects owned by the government, where it is hard to see how any people can benefit (Nor Baizura Basri 2007). Within Islamic communities large pools of funds exist through the Zakat mechanism which could be channeled for empowerment. “Zakat revenue can be spent under tamlik mechanism for providing an opportunity or raising productivity of the poor. Viewed from the long term perspective the poor would become in time self-reliant, hense reducing the national burden of spending money on social security schemes” (Khaliq Ahmad 2002). Likewise public structures like schools, mosques and community centres can be utilized for skills development and village meetings.

Marketing channels and the existing financial system can be utilized through the unit trust mechanism to collect subscriptions from consumers to fund venture development in rural areas. This would be a direct link between consumers and producers, where the consumers themselves could also become stakeholders in village enterprises and share the same visions and dreams. Many consumers are looking for such a spiritual connection and products can become a facilitator of their aspirations and dreams, assisting them in how they want to see themselves, through spiritual materialism.

This effort needs to be bottom-up rather than top-down with a community organization as the champion of the project. The track record of top-down initiatives is well documented and new approaches to rural development need to be experimented with. It is only when the rakyat feel that they own the project that it will be successful (Korten 1980).

Finally this type of initiative should not forget who it is serving and be organized around the needs of the people it is intended to benefit. The author of the Millennium Goals Professor Jeffery Sachs also criticises the clinical approach taken to poverty eradication, stating many remedies imposed by agencies are more symbolic than substantive (Sachs 2005, P. 266). Sachs recognizes that development must start with the people themselves who must be ready and willing to act both individually and collaboratively, rejecting the acceptance of their fate (Sachs 2005, P. 242). However a bottom-up approach through a community based organization in Malaysia will be seen by many as not reachable, particularly with the author advocating new crops and targeting new markets, and new branding paradigms with new technologies to the people of Kelantan, in what some would think that this is beyond the comprehension of the kampong people. But just as we sit back and tend to start agreeing, we must remember the advances the OTOP program has made just a few kilometres North of here in Thailand. It is important to select a group of kampong people who really want to be involved in the early stages[14].

Conclusion

God does not change the conditions of a people until they change their inner shelves

Qur’an 13:11

The new paradigm of poverty eradication is through the principles of entrepreneurship where communities are empowered by enterprise. Such a concept outlined above has all the ingredients available to be successful. What is needed is just some “idea champions” to embrace the concepts and make it happen with institutional support. Team Kelantan is the true secret behind a successful Brand Kelantan as such a concept requires cooperation across a broad spectrum of communities and organizations. The state’s economic development becomes the responsibility of the people themselves. From the point of view of natural product development, government initiatives in the past have tended to have lacklustre successes, as these commercial activities must be in the hands of highly motivated entrepreneurs to be successful. National crop agendas may not be necessarily relevant to Kelantan in the same way they are relevant to other states, as the structure of agriculture is almost completely small holder based. Such a concept has a better chance of success in Kelantan due to the “special sense of identity” Kelantanese feel towards their land.

Young graduates are the hope for future entrepreneurship in villages around the region, as the catalyst of change. They are tomorrow’s leaders and have a specific role to play in development. Students have access and knowledge to the information tools of our age. They are the potential mobilisers, liasers and leaders of village empowerment, should they choose to stay and do something. Graduates understand their own and also understand universities as a source of technology and can learn how to deal with relevant agencies for their cause. Graduates and the young are the only people who can build enterprises in rural areas in the future. Through linking all the elements together new organizations can be evolved that are based on the village model and link with consumers in developed markets in two way communication. Due to the advances in communication through the internet, graduates and villages now have unprecedented access to a wider international community of buyers, retailers, Fairtrade organisations and consumers directly, with which to communicate their intentions and seek support and customers; to advance the cause of empowerment to people in developed countries without third party agents.

*********************************************************************************

References:

Asma, A., (1995). Going Glocal: Cultural Dimensions in Malaysian Management, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysian Institute of Management, P. 179.

Biggs, S. D., (1995), Participatory technology development: reflections on current

advocacy and past technology development, in Biggs, S. D., and Dolberg, F., (Eds.),

Proceedings of a Workshop on Agricultural Science for Biodiversity and Sustainability in

Developing Countries, 3-7 April, pp. 11-20.

Dillon, J. L., and Virmani, S. M., (1985), The farming systems approach, in Muchow, R.

C., (Ed.), Agro-Research for the Semi-Arid Tropics: North-West Australia, St. Lucia,

Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, pp. 507-532.

FNN Staff, (2006),Innovators target cosmeceuticals niche, Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals, November, http://www.ffnmag.com/NH/ASP/strArticleID/1151/strSite/FFNSite/articleDisplay.asp (accessed 10th January 2007.

Hunter, M., M . 2008. Revolutionary Empowerment, SME-Entrepreneurship Global Conference 2008, 3 – 4hb July, Monash University, Australia,

Hunter, M. (2009). Essential Oils: Art, Science, Agriculture, Industry, & Entrepreneurship: A focus on the Asia-Pacific Region, New York, Nova Scientific.

Hunter, M, (2011) Herbs, Plant Extratcts, and Essential Oils, ASEAN Agro Trade Business Review, 2011-2012. Ministry of Agriculture and Agro Based Industry, Putra Jaya, Malaysia, pp. 214-227.

Kee, T. B., (1996), Monoculture in Malaysia: Impacts, Potential Solutions, paper presented to Monocultures: Environmental and Social Effects and Sustainable Alternatives Conference, Songkhla, Thailand, 2-6 June.

Khaliq Ahmad 2002 Intellectual Discourse Vol. 8, no. 2 (IIUM)

Korten, D.C. (1980). Community Organization and Rural Development: A Learning process Approach, Public Administration Review, Vol. 40, No. 5, pp. 480-511.

Ma’rof Redzuan & Fariborz Aref (2010). Path Analysis Model of the Development of handicraft Industries in Kelantan, Malaysia, Journal of American Science, 6(1), pp. 129-136.

Martin, A., and Sherington, J., (1997), Participatory Research Methods-Implementation, Effectiveness and Institutional Context, Agricultural Systems, Vol. 55. No. 2, pp. 195-216.

Nor Baizura Basri, Terinai Eyes Traditional Medicine Market in India, Bernama.com, 24th December 2007, http://www.bernama.com.my/bernama/v3/news_business.php?id=304142 (accessed 24th December 2007).

Sachs, J. (2005). The End of Poverty: How we can make it happen in our lifetime, London, Penguin Books.

Schumacher, E.F. (1975). Small is Beautiful: Economics as if people mattered, New York, Perennial Press.

Report of an Ad Hoc Panel of the Board of Science and Technology for International Development, Neem; A Tree for Solving Global problems, Washington D.C., National Academy Press, 1992, P. 34.

Shand, R.T. (1983). "The Role of Off-Farm Employment in the Development of Rural Asia: Issues", in R.T. Shand (ed.), Off-Farm Employment in the Development of Rural Asia, Australian National University: National Centre for Development Studies.

[1] The Schumachian model of development could be considered to be based on the belief of a self-reliant economy that supports human development within their cultural paradigm, supported by appropriate rather than imported technology. In contrast, Rostow advocated the transformation of traditional society to becoming an industrialized society.

[2] Since the cost of importing machinery is often very high, R&D institutions need to focus on developing the ability to fabricate equipment locally that are suited to local conditions and cost a fraction of the price of importation.

[3] For example, the Northern Corridor Economic Region Initiative was launch last July in Northern Malaysia. It aims to engage private ‘Government linked Companies” (GLCs) to organize production of small holders in the Northern states of Malaysia. No studies have ever been undertaken to determine whether local farmers are willinging to except outside organizations controlling their lands in what are called ‘mini estates’. See Northern Corridor Economic Region Socioeconomic Blueprint 2007-2025, Sime Darby, Kuala Lumpur, 30th July 2007, P. 28.

[4] This is not beyond expectations as this has been successfully done in Thailand through the One Tambon One Product Program (OTOP) in the provinces of Narathiwat, Yala, Pettani, Satun, and Songkhla.

[5]New crops are referred to as crops for the future in the Malaysian 2012 budget speech.

[6] Partly modified from Kee, T. B., Monoculture in Malaysia: Impacts, Potential Solutions, paper presented to Monocultures: Environmental and Social Effects and Sustainable Alternatives Conference, Songkhla, Thailand, 2-6 June, 1996.

[7] The opening up of the potential to develop new value chains is partly the result of new market niches like organic, Halal, and ethical-Fairtrade, and the advent of the internet as a means of quick and simple communication across the globe.

[8] This includes Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurveda, Aromatherapy, Cosmetic and flavor and fragrance industries.

[9] European regulations prohibit or limit the use of a number of plants or ingredients in cosmetic products. The absence or reduced levels of potentially toxic products in herbal extracts must be determined. At a European level, products classified as CMR (carcinogenic, mutagenic and/or reprotoxic) as defined in Appendix VI of EC Directive N°1272/2008 concerning the classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, except if a waiver is granted. The presence of other constituents such as pyrrolizidine alkaloids, furanocoumarins or molecules known to be allergens or sensitising compounds, is not desired because of risks of possible toxicity or harmful adverse effects they could cause. The question related with the ecological status of vegetal resources and the social and environmental impact that could result from their harvest has to be addressed. Recommendations related to culture and collection of plant starting materials have received sustained interest for several years, especially for medicinal plants. The system implemented for plant-based medicines is a relatively precise regulatory framework defined by Directives or Recommendations from European and other international organisations such as the European Medicines Agency or the World Health Organization. These good culture and harvest practices are summarised in two documents: For Europe, by the “Guideline on Good Agricultural and Collection Practice” of the Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products of the European Medicines Agency (2006) Outside Europe, by the WHO Guidelines on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for medicinal plants (2003). In reality, these regulatory frameworks applied to medicinal plants can also be usefully employed for supplies of starting materials destined for non-medicinal uses. This is because the above-mentioned documents are partly based on preparation work conducted by the EUROPAM (European Herb Growers Association) that drafted an initial document entitled “Good Agricultural and Wild Collection Practice of Medicinal and Aromatic (Culinary) Plants” in 1998. This document included all plant starting materials and their derivatives, used and marketed in Europe, usually designated by the acronym MAP (Medicinal & Aromatic Plants). The general principles of these directives can be broken down into four major areas: identity, quality and hygiene, regulatory compliance and environmental responsibility.

[10] This to some degree follows the OTOP example in Thailand. In addition direct marketing in Malaysia and Asia generally has a high consumer penetration. Kelantanese products should have a special appeal through such a channel with a Toyyib/Halal ethical and community approach.

[11] Private communication with Encik Azaharuddin Hassanuddin of Institute of Development Studies (Sabah).

[12] Principals set out for peoples companies by Dr. Subash Mentha, Bangalore, India, as communicated to the author.

[13] Oils produced through solar distillation would also have a neutral carbon footprint if biomass was produced organically and possibly fetch premium prices in the world aromatherapy market.

[14] Private communication with Assistant Professor Pairat Watcharapun Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Thailand.