Guest Editorial: Will Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) be putting pressure on AIA, Prudential, Tokio Marine, Zurich, Chubb and AIG to contribute to the mySalam Trust Fund?

Muhammad Hafiz Ipaldin

Disclaimer: This is partly a what-if piece. Any scenarios involving hypothetical usage of the RM 2.37 billion contribution by Great Eastern Holdings (GEH) or its remaining amounts are purely for speculative purposes. The misappropriation of the RM 2.37 billion amount from Great Eastern Life Assurance (Malaysia) Berhad’s (GELM) participating policyholders for GEH’s private purposes—fulfilment of the divestment condition—and for the benefit of its other subsidiary, Great Eastern Takaful Berhad (GETB), is strictly not condoned. The fact that this administration still chooses to continue with the mySalam scheme and contemplate expansion of its coverage to the M40 group is deeply disappointing. Any law-abiding, sensible, and fair-minded government should instead freeze the remaining MySalam funds and conduct a thorough and open investigation into this matter. The Attorney General (AG)—alas, were there a separate public prosecutor—should not only recommend the same but also seek to bring criminal charges against the various individuals—whether affiliated with in the past or present—in the Ministry of Finance (MOF), BNM, and GELM. The AG should also obtain a court order prohibiting GELM from distributing any further dividends to GEH and distributing any amounts from its ‘Estate’ not in line with the 90/10 rule, where policyholders receive at least 90% of the distribution proceeds, until all matters, including allegations of collusion involving GELM, GEH, BNM, and MOF; past underpayments to participating policyholders; and misappropriation of insurance funds, are resolved via the courts. The current administration should be forthright and forthcoming in addressing any and all claims, in particular on the misappropriation of policyholder monies, and publish the Independent Review Panel’s assessment report. If it truly thinks otherwise, that no wrong was done, then it should be bold enough to justify publicly why this administration believes the current generations of GELM’s participating policyholders within its closed funds have no right to a portion of the estate in line with the 90/10 profit sharing / distribution principle.

Recap: BNM has been diligently following up with foreign insurers on their promise to divest at least 30% of their stakes to local shareholders since 2017. In 2022, it was reported that end-2023 would be the final date for exercising the divestment option. With the passing of the reported deadline, foreign insurers are now required to contribute to the mySalam fund.

In the previous write-up (Billions up in the air....), it was mentioned that there was perhaps a minimum RM 6 billion contribution amount up in the air—figure based in part on 2022 earnings. This was an understatement. A minimum RM 10 billion contribution amount would be more apt—based solely on 2023 earnings. But wait, now that the Federal Court has ruled positively for Detik Ria as to their ownership of 49% of the shares in Prudential Assurance Malaysia Bhd (Prudential (Life)), Prudential (Life) is deemed to have fulfilled the local shareholding requirement—which in turn means they don't have to contribute to the mySalam fund. Lop off Prudential’s estimated contribution amount of RM 2.9 billion, and that would still leave ~ RM 7.1 billion on the table.

(Note: The Tokio Marine minimum contribution amount in the previous write-up is based solely on its life insurance subsidiary’s earnings—excludes its local general insurance arm)

A princely sum, and significant enough to run a modest nation-wide health-related social assistance / protection program on a sustainable basis. Add in Great Eastern’s RM 2.37 billion contribution or whatever’s remaining of it; invest the funds in Malaysian Government Securities and other investment assets in a ‘low to moderate’ risk portfolio, and we would have enough to dole out RM 250 million per annum, in cash or in kind, to lower-income groups and a RM 20 million annual operating budget—RM 270 million in total, slightly higher than 0.5% of Ministry of Health’s (MOH) annual expenditure (RM 41.2 billion in 2024) or around 4 - 5% of MOH’s pharmaceuticals allocation (RM 5 - 6 billion in 2024). All this and without having to touch the fund’s capital. In fact, it’s safe to expect the fund to be capital accretive, as even with a 3.5% annual investment return rate there would be residuals—after netting off program expenditure—to tack onto the capital base. Let's imagine then if the contribution calculation method was not based on ‘10x earnings’ but ‘15 - 16x earnings’. There would then be RM 14 - 15 billion in the kitty if GEH agrees to pay an additional RM 2 - 3 billion, allowing an annual program allocation of RM 450 million. Close to half a billion right per annum for an enhanced version of Peka B40 with expanded objectives, reach and better awareness initiatives. More funds for medical device aid, ‘not covered by MOH or unavailable due to budget constraints’ therapeutics / medication, small incentive payouts and the like. Also, with a bigger allocation comes better negotiating power, helping to further lower costs. The most important aspect in the program’s design, its sustainability, is preserved. Within 5 years, the scheme’s participants would have availed themselves to over RM 2 billion in health social assistance / protection with only an operating budget of RM 200 million. Sounds ideal, doesn't it—on paper at least? The biggest gripe, from ‘have a heart for the poor’ Lim Guan Eng, was that the local shareholding requirement would only benefit a select few at the expense of the deserving masses.

The cash contribution, said Guan Eng, is in line with the government’s objective to provide a special and direct focus on the B40 group, so that it “will benefit millions, and not just a select few ” from the otherwise stake sale in the insurers.

“For those who say that the RM2 billion can be used for other purposes, have a heart for those who face hardship.” Lim was responding to the criticism that the RM2 billion contributed by Great Eastern Life should be used to boost the public healthcare system.

Hence, the impetus for a social health insurance scheme in the form of mySalam. This is not entirely convincing. Wouldn't Peka B40 or any other social assistance program be of equal, if not more, benefit to the B40 compared to an insurance scheme? There wouldn't be the multiple fees for management and taxes, as is common in an insurance setting—the savings from which would be channelled to the B40. And if helping the lower income groups was truly the intention—we do have quite a number of institutional investors—how is purchasing those shares, placing them in a specific fund with other investment assets to be managed by these institutions, and partaking in their dividends and capital gains for the various causes, not an acceptable proposition? Didn’t Fuziah Salleh, current Deputy Minister of Domestic Trade and Cost of Living, moot something along those lines? The Amanah Saham Rahmah proposal comes to mind.

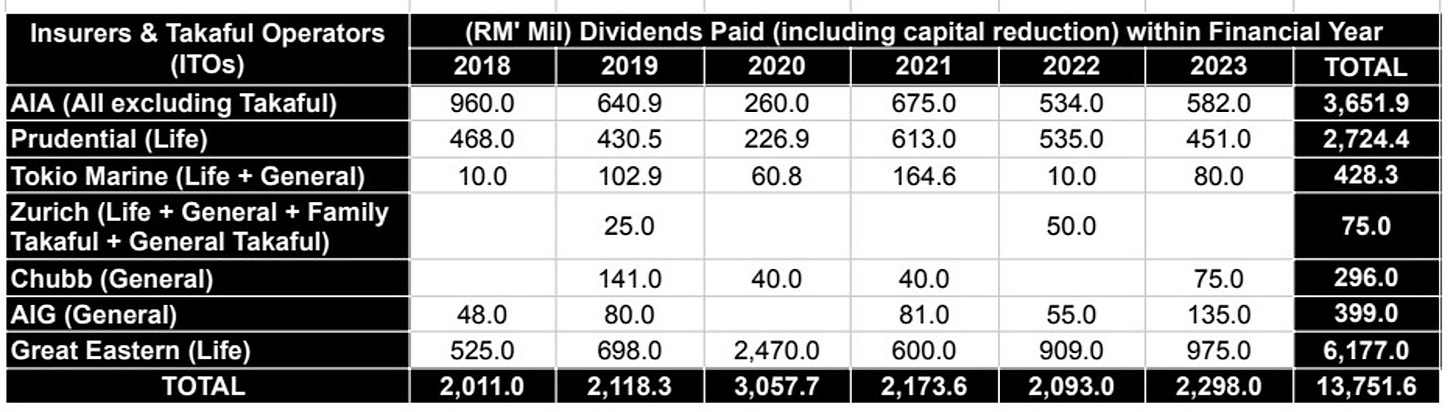

The basic premise for following through with the divestment policy was that foreign insurers were repatriating huge sums from the country without much in return to the local economy. The Edge had previously reported, “Bank Negara estimates that a total of RM16.5 billion, or 70% of total profits attributable to foreign shareholders of insurers, were repatriated over the period from 2008 to 2017 in the form of dividends”— an average of RM 1.65 billion per annum. Impressive, but not as impressive as the amount foreign insurers repatriated in dividends (including capital reduction) after that jolly good period—around RM 13.8 billion between 2018 and 2023, an average of RM 2.3 billion per annum.

(Note: Out of that amount, GELM repatriated to GEH RM 6.2 billion, or 44.8% of the total repatriated by foreign insurers between 2018 and 2023. Excluding the RM 2.37 billion amount pillaged from their participating policyholders for mySalam, that still amounts to RM 3.8 billion in dividend payments within 6 years. Would the average reasonable person still think RM 2.37 billion is a fair contribution amount reflective of 30% of GELM’s future earnings potential—that’s a valuation of just RM 7.9 billion or 2.1 times its past 6 years’ ‘clean’ dividends of RM 3.8 billion? Even 99 Speedmart has a better valuation (RM 13.9 billion) than GELM—apparently the RM 13.9 billion valuation is actually at a discount of 17% to its fair value of RM 16.8 billion. GELM’s earnings are at least 2 times as high as 99 Speedmart’s and its average dividend to comprehensive income ratio is above 70% compared to 99 Speedmart’s dividend policy targeting 50% net profit. No cap—GELM is a cornerstone investor in 99 Speedmart)

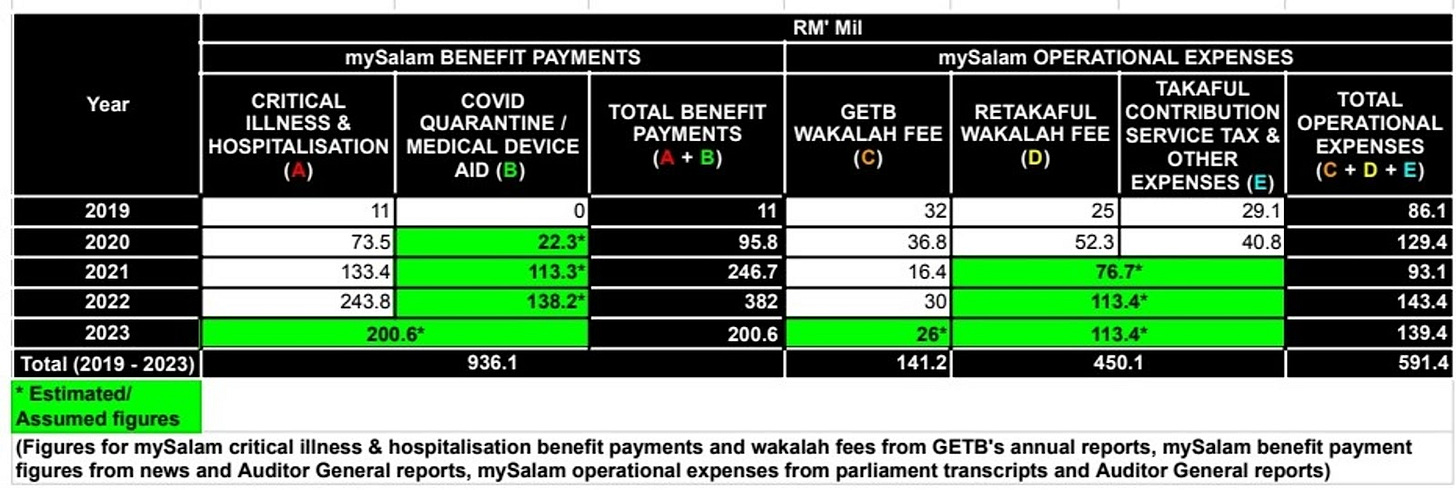

Whether it’s outright purchase of shares or contributions by the insurers, it's always how the assets / funds are put to use that matters. These things (social programs) tend to look good on paper—as they usually are crafted to that effect—how well it fares is something only ferreted out during implementation. Take the Peka B40 route; there could be a lack of awareness of the program and procurement issues—exclusivity, collusion etc. In that spirit, it would be in our collective interests to analyse mySalam’s performance. It was around a month ago that Lim Hui Ying (LHY), Deputy Finance Minister, disclosed the RM 936 million disbursed between 2019 and 2023 in mySalam claims. Sounds like an accomplishment, on the face of it. Not so when accounting for the fact that the RM 2.37 billion contribution was meant to be exhausted within 5 years—notwithstanding its unsustainability, in and of itself a program design flaw. It becomes even more appalling when the expenses are laid bare and the actual claim payments are broken down and analysed further. Were it not for the happenstance of COVID-19 coinciding with the running of the scheme, the actual claims paid by the fund might have only amounted to around RM 0.55 billion or RM 110 million per annum between 2019 and 2023—‘might’ as we are left to work with only patchworks of information.

GETB was originally contracted under the scheme to cover hospitalisation benefits of RM 50 per day for a maximum of 14 days per annum, and a one-off lump sum payment of RM 8000 when diagnosed with any one of the 45 critical illnesses for Malaysians within the B40 group. When COVID-19 entered the picture, mySalam’s hospitalisation benefits was then extended to cover the ‘quarantine’ period—both home and MOH facilities quarantine. The scheme’s coverage was also further expanded to include medical device aid. To recap, the estimated claim payments of RM 0.55 billion was only for the original coverage, and the rest, ~ RM 400 million, was for the additional COVID quarantine benefit payments and medical device aid. This distinction is important to keep in mind; its salience will become apparent later on. The operational expenses, on the other hand, can be estimated at over RM 0.59 billion, or RM 118 million per annum, between 2019 and 2023. Around a 1:1 and 1.6:1 ratio between claim payments for original and enhanced coverage to total expenses incurred. Can a fully funded social assistance / protection program be said to have met its objectives and be deemed successful when it takes a dollar to give a dollar or a dollar and a half? The expenses break down to about RM 141 million in GETB wakalah (management) fees; RM 206 million in retakaful (reinsurance) wakalah fees; and service tax of RM 247 million—again, these are all just estimates, so please be mindful.

In what way does it make sense having a government-funded social assistance / protection scheme pay service tax, and pay for the scheme service provider’s hedging (retakaful) of its own risks? That’s almost half a billion ringgit, in total for these two charges, that could have gone to the B40 group Guan Eng was so concerned about. And why does the government care more about funding the private risk management concerns of GEH—if GEH doesn't care enough about the sanctity of its subsidiary’s balance sheet to fund it (retakaful) themselves, why should the government be bothered by it? Let BNM, GEH, and GETB sort it out. It's their Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) on the line. And this poppycock nonsense about the government needing to pay for retakaful wakalah fees as there was the off-chance that the annual premiums paid wouldn't be sufficient to meet claim payments or they might hike up the premium amounts in lieu is just that. It's not the government’s concern. Period. The initial imposition by BNM was for GEH to bear all retakaful costs, and the RM 2 billion contribution proposal was envisioned to be sufficient for 5 years worth of coverage for the B40—btw, even with the mySalam fund covering retakaful fees, it didn't stop GETB from hiking up premium amounts beyond what was ‘necessary’ to cover the additional benefits (FYE 2022 mySalam premiums was over RM 1.2 billion). So by all means, please hold BNM and GEH accountable. Why is it so hard for the government to do just that? It's bad enough that they are benefiting both operationally and financially from the mySalam wakalah fees. There’s at least an estimated 25% profit margin in the fees—amounting to over RM 35 million in total profits for the 5 years (2019-2023)—and it (the fees) allows GETB to defray its staff and other fixed costs.

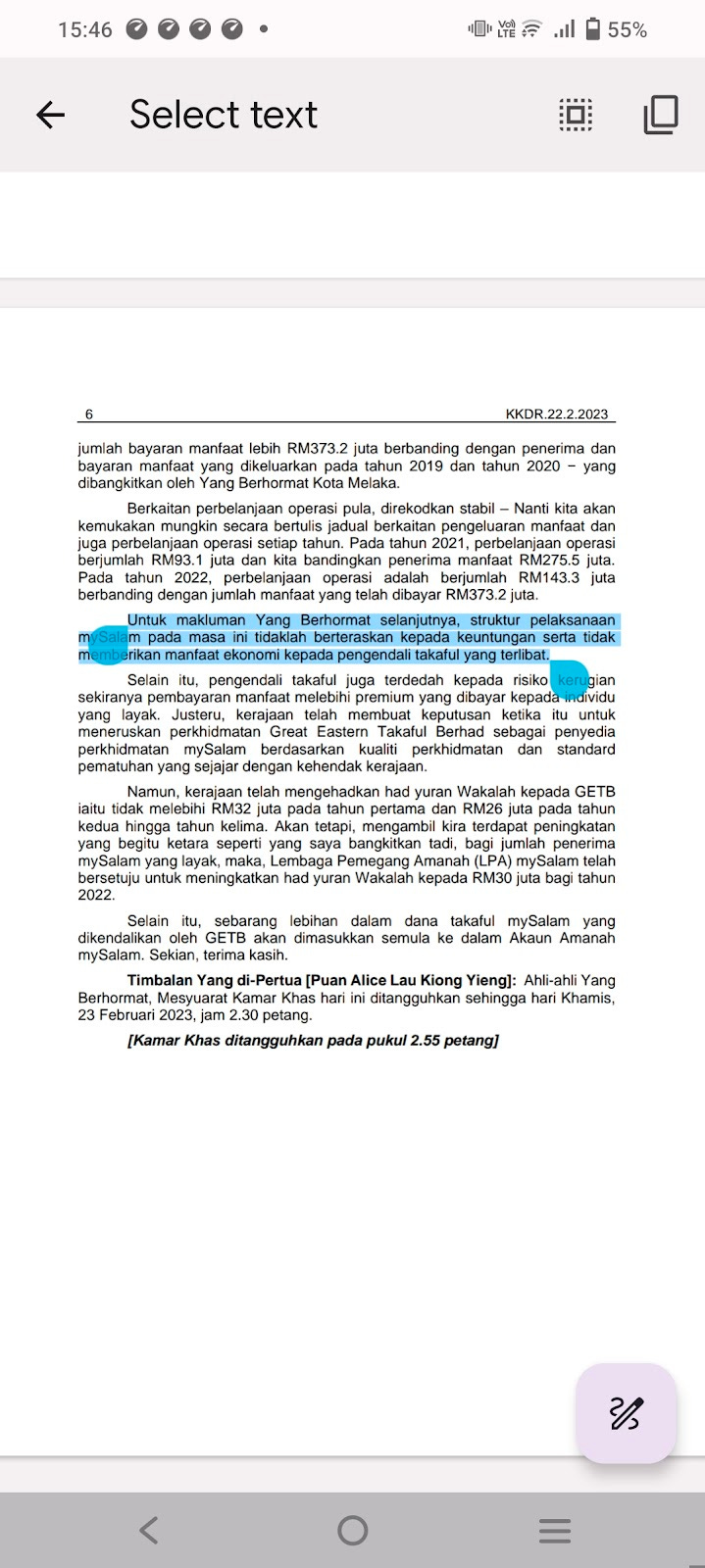

Steven Sim, do you still hold this statement to be true—that GETB did not financially and economically benefit from administering the mySalam scheme?

The total wakalah fees tally, including retakaful, is either close to or higher than RM 350 million—ALL FOR GEH’s BENEFIT, AT THE EXPENSE OF THE ‘RAKYAT’. Was this scheme set up for failure from the get go? Why bother with its implementation in the first place? Might as well have funded a better version of Peka B40.

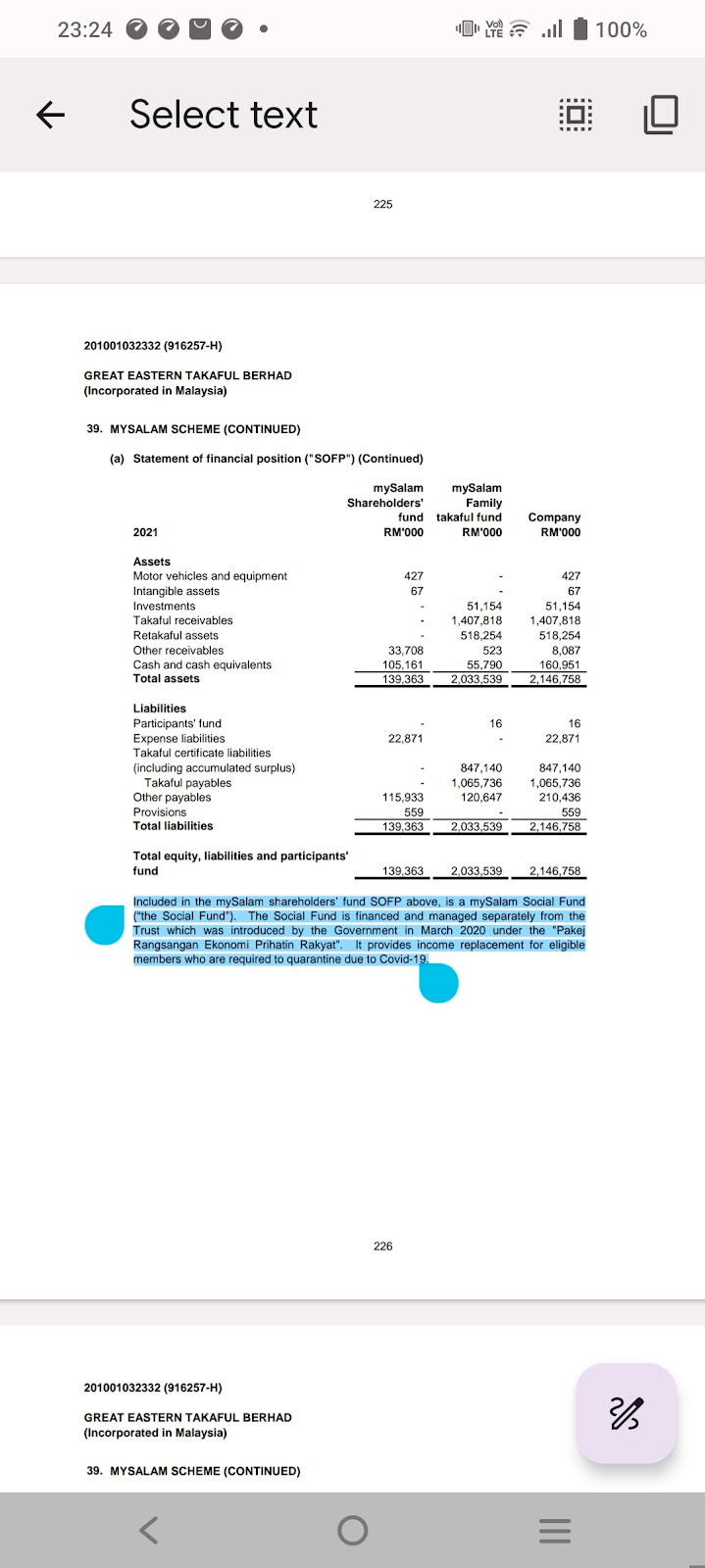

Speaking of Peka B40, till date, it is still unclear as to which fund or budget is responsible for footing the bill for mySalam’s additional benefits. On the one hand, there are disclosures within GETB’s financial statements explicitly mentioning the COVID quarantine benefit as managed and financed separately from the mySalam Trust Fund under the ‘Pakej Rangsangan Ekonomi Prihatin Rakyat’.

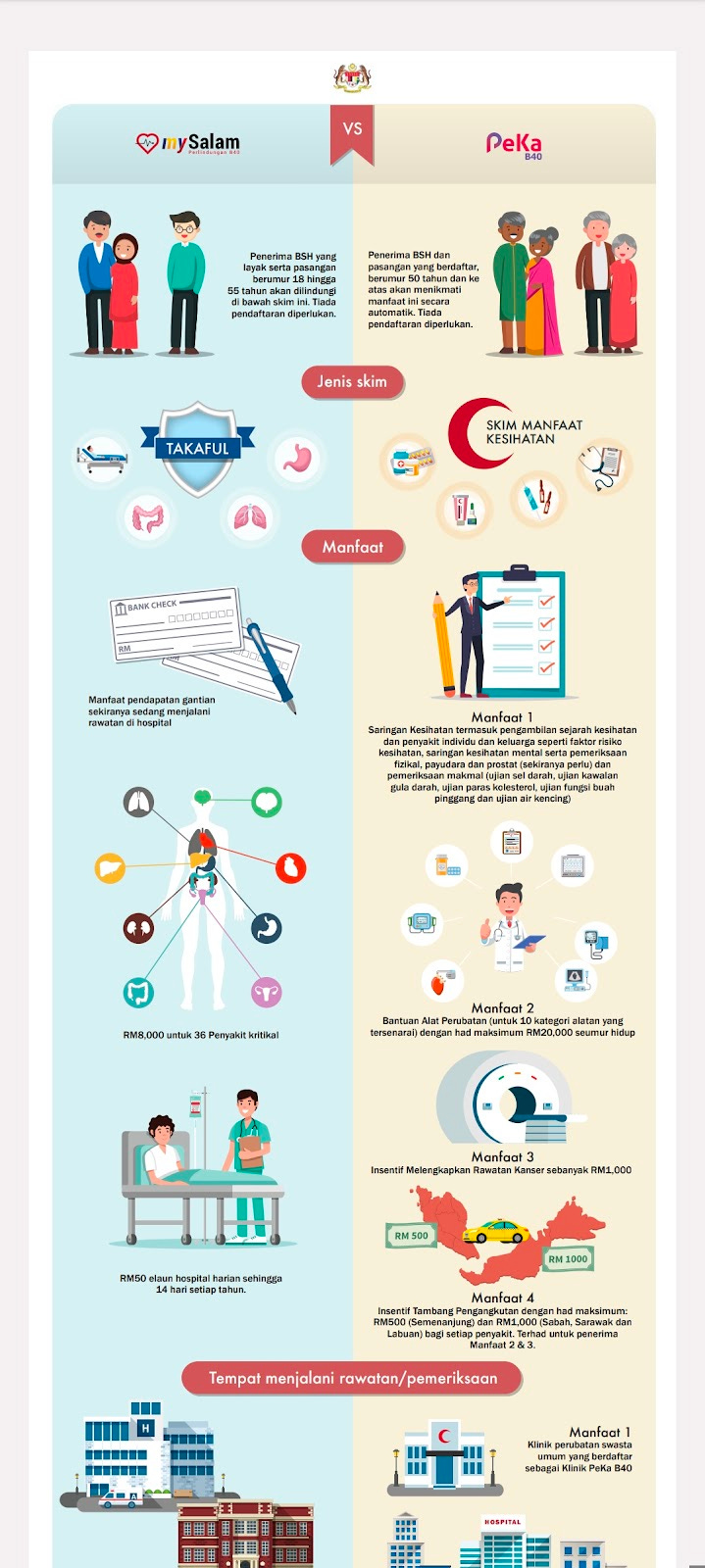

There is not a mention of medical device aid coverage on mySalam’s website, and a mySalam vs. Peka B40 infographic on the site makes it painfully clear that the aid is only provided for by Peka B40.

And then there are the government disclosures within parliament clarifying coverage of the above additional benefits under mySalam. So, which is which?

Is a part of Peka B40’s budget, for medical device aid coverage, funded by the mySalam fund—if yes, exactly how much? How about the COVID quarantine benefit—is it separately financed from the fund, and if so, how much did the government allocate to finance it? To GEH’s management: Are GEH shareholders, including and especially their minority shareholders, aware of any of the additional benefits covered under mySalam? LHY should not only clarify on the above but also provide a detailed breakdown of all the mySalam benefit payment amounts and operational expenses, by each separate type of benefit and expense, for each year between 2019 and 2023. She should also disclose the fund’s remaining balance, including amounts contributed by investment returns; expected fund outflows until end-2025; and on the government’s plans for the remaining balance by then. Oh, and if possible, LHY should brief the rakyat on why BNM is faltering on getting the other foreign insurers to toe the line on the divest-or-contribute policy. Maybe, let's make it her KPI to get foreign insurers to contribute at least another RM 13 - 14 billion to the mySalam fund by end-2024. I mean, she clearly doesn't see any issue with GEH pillaging GELM’s policyholder monies for their private purposes, judging by her rara-ing for expansion of mySalam coverage to the M40 group. So, if everything is hunky dory, it should be mou man tai for a formidable member of the Kit Siang clan to tai-chi away any inconveniences and settle these small matters. Speaking of clans, there’s one teetering on ‘The Edge’. Can't help but recall this ‘wishes it aged like fine wine’ gem:

As an aside, the RM2 billion is understood to come from Great Eastern’s RM10 billion estate fund, which represents its accumulated profits over the years from its pooled funds, including from former policyholders who forfeited previous payments when they dropped out.

Its policyholders are entitled to at least 90% of the estate fund while shareholders are entitled to the rest. Bank Negara Malaysia has pushed insurers to explore utilisation avenues for such funds since 2015. But the share of estate funds is debatable; the 90:10 ratio is not carved in stone.

The 90:10 rule has its origins in Insurance Regulations 1996 ‘Regulations’, which was itself enacted under the repealed 1996 Insurance Act ‘The Act’. All rights and interests of policyholders, and obligations of insurers towards their policyholders, as stipulated within The Act and Regulations are preserved under the savings provisions within the Financial Services Act ‘FSA’—which came into force in June of 2013. What this means is that the obligation of an insurer to distribute participating fund surplus in line with the 90:10 rule is still maintained under the FSA. And guess what, the Federal Court upheld the primacy of the savings and transitional provisions under the FSA when it ruled for Detik Ria in its dispute with Prudential Corp Holdings Ltd and The Prudential Assurance Company Ltd. on the ownership of 49% of the shares in Prudential (Life). In particular, the judgement upheld the primacy of Section 272(l) of the FSA.

Section 272(l) any right, benefit, privilege, obligation or liability acquired, accrued or incurred under the repealed Acts, shall continue to remain in force under this Act;

I'll leave you lot with the particular provision—within the Regulations—on the obligation of the insurer to distribute to policyholders at least 90% of the total amount distributed, from the participating fund, in any future distribution.

Section 11.(4) Where an appointed actuary does not recommend the allocation of the entire surplus, the policy owners or the shareholders shall have no right to require allocation of the surplus carried forward unallocated, except on the recommendation of the appointed actuary in accordance with subregulation (2) as at the end of a subsequent financial year.

Subregulation (2) refers to the 90/10 rule

You guys can decide for yourselves on whether policyholder monies were pillaged and whether the other foreign insurers are going to toe the line.

Subscribe Below: