Motives push people to perceive, think and act in specific ways that attempt to satisfy needs[1]. Motives often stay unconscious in a person, as the person doesn’t know exactly what they want, yet these motives remain powerful influence behind thoughts, feelings and behaviors[2]. People differ in their types and strength of motives, taking them on different lifetime journeys with different outcomes. For example, Anita Roddick, the founder of The Body Shop may have been personally committed to the environment, education and social change, while Jack Welch and Bill Gates were more motivated by competition and winning, leading to completely different types of organizations and operational philosophies, while all being considered more than successful. Motivation is also situational where for example one can see the higher rates of entrepreneurship among migrant populations in developed countries[3]. Studying motives can assist in answering the question of ‘why people do what they do?”

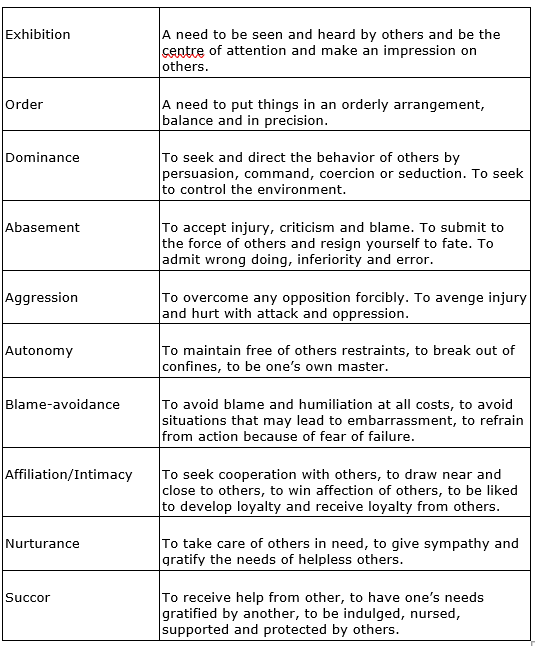

Motivation is not static. There are two sets of motivational factors. The first set that motivates a person initially usually involves need, responsibilities and obligations. Some of these motivations may arise from some form of trauma like job retrenchment. A second set of motivators come into influence once a person has established something and involves motivational factors related to the tasks themselves. These higher order motivations have a lot to do with achievement, satisfaction, recognition and fulfillment. Motivational goals often keep moving as one progresses thus maintaining tension and drive in the person. For example, an original motivation may have been to serve a particular geographic area, but as time goes along, ambitions and motivations grow to new and larger areas. When one does meet a goal or objective, then that goal or objective ceases to be a motivator and complacency can set into the person. A list of common motivational factors is listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Some Common Motivational factors[4].

Motivation appears to come from the ego portion of the psych[5]. The ego gives a person a sense of purpose and this is where ‘the urge to make a difference’, ‘to be respected’, ‘to be admired’, ‘to be wealthy’, ‘to be successful’, ‘to control others’ and ‘to be the best originates’. The ego holds emotions of self-esteem, the sense of achievement, envy, greed, hate, anger, anxiety, fear, guilt and empathy which are the building blocks of motivators.

How motivation makes things happen

An opportunity is a “potential” for change and this needs energy to accomplish. Motivation is needed to trigger the process of seeing new realities that can replace the present situation. Motivation is also needed to act upon the vision of the new reality. Robert Fritz conceptualized the phenomena of ‘structural tension’, using an elastic band to demonstrate the concept and energy involved[6][7]. When an elastic band is between two fingers and the fingers are close together, there is little or no tension. However, when the two fingers move apart, the tension on the elastic band increases. If one finger represents the current reality and the other finger represents a vision or potential reality, the tension of the elastic band can demonstrate the relational tension between the fingers at different distances. So if the elastic band is not stretched, no energy exists and nothing happens. If the present reality and vision or potential reality are far apart then there is great tension and potential energy ready for action.

According to Peter Senge structural tension[8] also produces ‘emotional tension’ represented by anxiety, sadness, discouragement, hopelessness, or worry[9]. These emotions can act counter to the structural tension, as these feelings discourage a person from taking action upon any vision. It all depends upon how people cope with emotional tension to determine whether action is taken or ideas just remain as passing daydreams. People cope differently to emotional tension – some people are better than others in handling negative emotions. Strategies to reduce emotional tension may include abandoning the vision or moving the vision closer to the present reality.

Motivation is both situational and relational. How we react to things always depends upon the situation and our relationship to others. According to Edgar Schein the human psych is not fixed as there are differences between people[10]. Money incentives may not motivate someone who already has a lot, and status may not matter if one sees themselves as already having a higher status that a proposed activity provides. Yet another person may see the same opportunity as a chance to make a living or gain some attention and notoriety[11]. Therefore a great determinant of what we do is learned from our social environment. This includes our family, education, socio-economic standing, culture, our own sets of beliefs and the circumstances of the immediate time and place we are present. Thus different people will have different patterns of motivation, attitudes, perception from different relative positions of status, need and wants.

When an individual has some form of vision, tension begins to build up within his or her psych. The gap can create positive or negative feelings. When positive, a person will feel ambitious, energetic and ready for a challenge. When negative, a person will feel powerless, distraught, think negatively and may lack sel- esteem. A positive effect of the gap between a person’s reality and vision is the creation of a source of psychic energy that will drive an individual’s creative curiosity. This is the tension needed to help drive the creative process.

A gap based on delusion or fantasy about something that cannot be realistically achieved will usually result in a person having to self-justify their personal failings. This may manifest itself in external blame or feelings of low self-esteem and self-efficacy. A person with no gap between their reality and vision will not have any feeling of need to be curious about anything and will have very little urge to think about new possibilities as they accept the way they are.

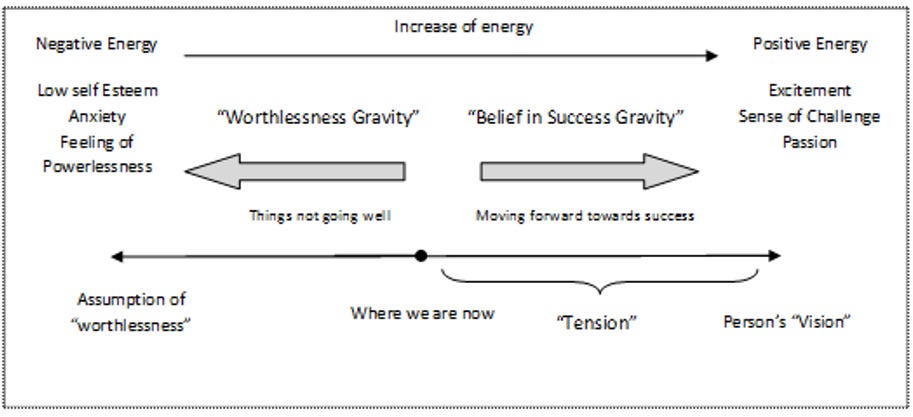

Tension built up in a person because of the gap between their personal reality and vision can be released in two ways. The first way is to achieve the vision thus closing the gap being the most desired solution. This release will take a period of time to bring reality in line with vision, providing a wide range of emotions during the journey which include a sense of challenge, excitement, and passion on one side and frustration, impatience and contemplation on the other side. The second way to reduce the tension is by lowering the vision, which leads to disappointment, low self-esteem, anxiety, and a feeling of powerlessness. The vision may incrementally decline to repeated poor achievement within a domain that a person has a vision. This may result in the individual slowly lowering the expectation and explaining the failing away, i.e., coming 4thwas good enough.

Tension created by the gap can create positive energy. The vision acts as a motivator, something that creates a frame of positive feelings which creates a good environment for creativity. However, deep within our psych, people have self-doubts about being able to achieve their visions. There is a dormant belief that we are unable to fulfill our desires because as children we learn our self limitations[12]. This is important to our self-preservation and ultimate survival that continues into our adult life[13]. Thu.s this leads to another deep unconscious assumption that we cannot always have what we want, which can create a deep inner feeling of worthlessness. So vision on one hand creating a feeling of challenge and excitement and a deep feeling of worthlessness on the other creates a paradox where our personal energies can be channeled in a number of ways. This paradox can lead to a loss of psychic energy where we decide to let the vision erode. Alternatively, we may question whether we really want the vision and psychically manipulate ourselves into greater efforts to pursue it. Finally. we may find (or sub-consciously create) obstacles as an excuse for our failure to meet the vision. Our deep assumption of self-limitation may lead to a fear of failure, which in the extreme could lead to the avoidance of challenges. Alternatively. this paradox may lead to total focus and dedication, where all obstacles can be overcome. Focus and lots of reserves of psychic energy can in the extreme lead to compulsive behavior, which may be good for achieving visions but have secondary costs associated with success like a neglected and failed personal life[14].

When there is a strong belief that a vision can be achieved, psychic energy will increase as clarity and success reinforces the belief in successfully achieving the vision. The strength of the belief in success has more “gravity” than the person’s deeply held assumptions of worthlessness. However when things don’t go well and there is personal doubt about achieving the vision, psychic energy greatly decreases and the “gravity” of the deep assumption of worthlessness is stronger than that of the vision and pulls the person towards giving up. This is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Forces of the Motivational Trigger.

Recently, the concept of energy has been related to a person’s ability to be creative and achievement. However, there is very little agreement on the definition of energy, what it really is, what it does and no way has been found to actually measure it directly[15]. This is an area that will probably be given much more attention in the near future, particularly in the discipline of entrepreneurship. A number of different types and terms for human energies have been cited, but probably out of these, three are of importance and cover different overlapping descriptions. The first of three energies is our physical energy that we use to do physical things like moving from place to place, running, sports, and any other activity that requires kinetic movement. Our physical energy is managed by food for fuel, rest and exercise to build strength and discipline. The next energy is our emotional energy which carries our general emotions like happiness, surprise, hate, envy, and jealousy, etc. Emotional energy helps to give us focus, interest and attention to different things we sense, encounter, or exposed to and is one of our primal mechanisms to keep us alert to danger in the environment[16]. Finally, there is our mental energy which fuels our ability to make calculations and undertake judgments. Mental intelligence is where our problem solving skills and creativity are generated. Sometimes emotional and mental intelligences are called psychic energy, but breaking them into two separate energies allows us to understand the very different roles they play in our life. These three energies are all interrelated, where for example a physically tired person will not perform mental calculations well, or an emotionally tired person will not be able to undertake either physical or mental things very well.

Our energy is chemo-electric in nature, where proteins, enzymes and other electrically sensitive chemicals produce and transfer electricity through our neuro-system to make us move, feel and reason[17]. Our energy links our cognitive and kinetic systems together as one interdependent system something like the Chinese concept of Qi[18] that governs our bodily, mental and emotional disposition. Energy is a dynamic force that fuels all our processes and like all energy behaves according to the first law of thermodynamics where it can be stored, released, focused and drained according to stimulation, demands, needs and distractions coming from the environment and our inner self.

Our physical energy is responsible for our kinetic movements, however, like nutrients, rest and training; our emotional energy also affects our levels of physical energy. Take for example an athlete overly nervous before a race, feeling ‘butterflies in the stomach’. With extreme anxiousness and fear (presumably of losing or performing poorly), the athlete’s physical energy will begin to drain making the person feel lethargic, tired and weak. This contrasts with the athlete who is ready to do their best, focused and determined to perform well and ready for the challenge without allowing doubts and anxiousness to drain his or her energy. Another example is the inability to reason logically when one is in a state of anger and the tiredness one feels after being angry. These different states show the interconnection between our various types of energies.

Emotional energy helps a person to deal with everyday frustrations, conflict and pressure. Our emotional energy is influenced by the surrounding environment, people, objects and events. Emotions in the form of moods[19] ebb and flow during the day, week and month. We are most often unaware of our moods which tend to influence the way we think about things[20]. Our emotions are triggered by a potential crisis, a crisis, our health, our concern for something or general stress. A person with a high level of emotional energy will be able to cope with the normal stresses of the day while a person with a low level of emotional energy will quickly succumb to any crisis, becoming stressed, anxious and/or frustrated very quickly. Under such situations a person losses focus, where their attention becomes diverted on other tasks that lower general energy levels.

Emotional energy is a source of determination providing a person with the emotional motivation to get on with a job whether it is physical or mentally orientated. Emotional energy provides our enthusiasm, drive and resilience to do things. This is fine in a person who has a clear mission to attend to, but where a person’s emotions are deluded with paranoia, compulsiveness, depression, or other forms of neurosis, their emotional energies are diverted into the fantasies that these various pathologies generate[21]. For example, a paranoid person will spend all their emotional and mental energies on suspecting conspiracies against them, leaving little energy available for creative or other problem solving issues facing them. These types of emotions lead to immense fatigue and inability to function logically. Emotional balance is very important so that both our physical and mental capacities are at their optimum.

Mental energy is very important for creativity and supports two types of cognitive operations. The first is the ability to make mental calculations and draw inferences from logical and spatial relationships. The second is the ability to make judgments, recognize similarities across different categories of information using induction and logical reasoning[22]. We tend to slow down in the ability to make quick and accurate mental calculations during aging but on the contrary improve in our induction and logical reasoning with age. Intelligence is not as important to creativity as is attention and focus without distraction. Mental energy is created through our interest, desire, curiosity, passion and concern for something. Our mental energy levels can be affected by drugs, food, sleep deprivation and disease states[23].

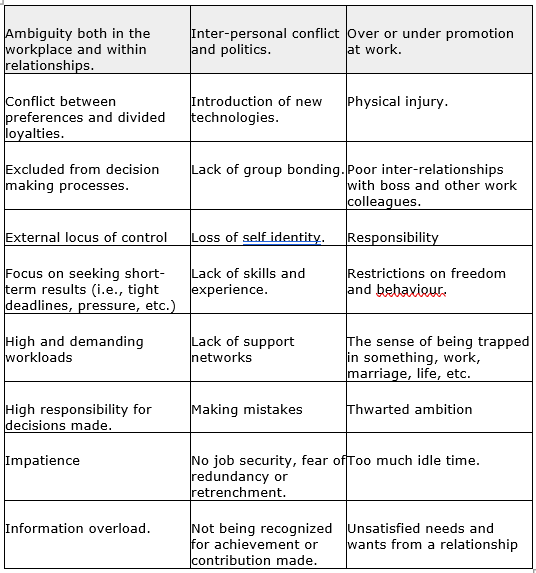

Creativity can be blocked through a number of situations. As mental cognition requires attention, the mental energy required to think can be lost through just being ‘too busy to think’. Too many demands upon a person take up full cognitive attention, leaving no cognitive capacity for anything else. Therefore people working all day without time to think will tend not to be creative. Likewise distraction will divert attention away from potential creative tasks. People looking after children, working all day, watching television will be distracted and not have the time and focus to be creative. People concerned about survival will not have time to ponder on novel things unless it is directly related towards self preservation. A person concerned about monitoring threats to their own ego will also divert their mental energies away from creative effort[24]. As we have seen earlier in this part of the book, people who are paranoid or compulsive are too distracted by their delusions to be creative, unless it is tied up with their delusions. The utilization of defence mechanisms to deny realities takes up a lot of mental energy. Lazy people without self discipline will not have any motivation to apply any mental energy to looking at novel issues. They will not be bothered to question anything as their objective is to remain detached and apathetic towards anything requiring the use of energy. Finally, there are a number of people who don’t know what to do and where to look for things. They rely on the guidance of others and don’t know how to question things. Table 2. provides a list of situations that drain a person’s energy levels. Lack of stress on the other hand seems to build a person’s energy and sensitivity[25].

Table2. Some situations that can drain energy.

Creativity is about energy, attention and focus rather than great intelligence. Creativity requires long hours with great concentration, consideration and reconsideration rather than brilliance. Creativity requires strong mental energy. Creative people are not hyperactive, but have high amounts of mental energy[26], which they can control. People with average intelligence can be very creative if they have the time and curiosity to look at things in novel ways. People with very high intelligence may not have any curiosity and as a consequence not consider novelty and accept things as they are.

Personal discipline is the ability to control one’s energy and maintain focus on what one wants to do. Self discipline maintains focus and prevents a person from needlessly wasting energy on unnecessary issues. Personal discipline is important in keeping momentum towards desired goals and objectives. Poor self discipline leads to an inability to make completion of tasks and the failure to get things done.

Personal discipline is not a given in people and can only be slowly developed through repetition and training. This is something similar to training for cycling, swimming, tennis or running, etc. One needs to build general fitness (physical energy), a positive and confident frame of mind (emotional energy) and calculate out strategies and tactics to achieve optimum performance and achieve set goals. Training can only be built up gradually to prevent injury and exhaustion through building capacity incrementally on strength. The process of creativity must be disciplined to be relevant to what the person wants to be and where the person wants to go.

Motivational Biases: Be careful what you wish for.

Finally one must be aware of motivational bias. Motivational biases are a group of mechanisms that influence perception and decision making. Unlike defence mechanisms which tend to be emotionally driven and cognitive biases which are based on what someone expects to see, motivational biases are based upon what someone wants to see. Motivational biases occur when a person has an interest in reaching certain conclusions or see things go a certain way. Motivational biases can be both unconscious and conscious phenomena, where in some cases a person is aware of the bias in their thinking, i.e., ‘plain wishful thinking’ may motivate perception and decisions.

Motivation influences perceptions and decisions made in most areas of life. For example, people in a high income bracket may have a negative attitude towards the poor and blame them for their own plight, while people in a low income bracket may see poverty as a situational factor such as government failure[27]. People who are declared bankrupt tend to blame the petitioner and not themselves[28].

Motivational biases are built into occupations, where for example an architect will tend to under or over estimate the materials required as the situation requires and the building contractor may tend to overestimate the materials required because there is an interest in building a strong structure[29]. Technical experts may under-estimate potential risks with technologies they are familiar with in their own disciplines[30]. Salespeople may have a tendency to underestimate their sales budgets if incentives are based on those figures. Loyal employees of a company may make decisions which they feel may please their superiors. Upper management may lower risk probabilities in annual reports for the benefit of stakeholders. People may stick to a particular line of argument, rather than agree to change because they believe that maintain the same cause of action is the most beneficial for the firm. Likewise, public figures will be reluctant to give credence to alternative views in the risk of been seen as weak[31]. Ego-centric people may just want to impress others that they are knowledgeable about a subject area.

Motivational biases are present in our self-view of the world. Motivational bias as part of healthy cognition, as it assists with making quick decisions in life[32]. Motivational biases often disappear when a person is depressed[33] and when they are asked to estimate the probability of the same events happening to others[34].We tend to overestimate our skills and abilities and influence on ‘making things happen’, even if we have no influence at all over the event[35]. This boosts our self-esteem, which may be a very important aspect of opportunity. An underestimate of one’s success could bring apathy about potential opportunities, resulting in missing out[36]. Without seeing ourselves as capable people we would not have any confidence to take up any new opportunities.

Motivational biases are often difficult to detect as they are well concealed. Looking at ourselves is very difficult, just like a fish trying to see water. Each of us believes that we take an objective view of the world and impartial, while others are partial and biased[37]. One should be vigilant in looking for motivational biases in external information like conference papers, newspaper and consultant’s reports where the authors’ may have a vested interest in them. It is a very common situation where a person has a vested interest or conflict of interest that is not obvious to his/her audience.

Motivational Biases affect cognition in both perception and thought. Motivational emotion combines with cogitative processes to help form judgments[38]. Sometimes motivational biases can challenge cognitive biases in an antagonistic manner. Put in Freudian terms, the rational super-ego and the logical ego conflict with the impetuous and passionate id. This conflict can lead to several types of neurosis that undermine and disrupt adaptive functioning. Therefore, in modern psychology the cure of neurosis echoes the victory of reason over desire, i.e., ego and super-ego forces winning over the id[39]. Therefore all cognition must have some motivational underpinning in certain circumstances[40].

Motivational factors act to direct cognitive activity according to interest: giving great weight to desirable information and low weight to undesirable information[41]. Therefore, motivational biases can be seen as a kind of cognition itself. A motivational bias is an intrinsic knowledge structure, a schema which can be activated through semantic priming from cognition, resulting in human judgment[42].

Originally published in Orbus July 2012

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

Notes & References

[1] Larsen, R. J. and Buss, D. M. (2005). Personality Psychology, 2ndEd., New York, McGraw-Hill, P. 339.

[2] Barembaum, N. B. and Winter, D. G. (2003). Personality, In: Freedheim, D. K. (Ed.), Handbook of Psychology: History of Psychology, New York, John Wiley & Sons Inc., pp. 177-203.

[3] Kloosterman, R. and Rath, J. (Editors.), (2003). Immigrant Entrepreneurs: Venturing Abroad in the Age of Globalization, New York, Berg.

[4] Adapted from Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in Personality, New York, Oxford University Press.

[5] Bolton, B. and Thompson, J. (2003). The Entrepreneur in Focus: achieve your potential, London, Thomson, P. 79.

[6] Fritz, R. (1991). Creating, New York, Fawcett Columbine.

[7] See Robert Fritz’s short clip at http://www.robert fritz.com/index.php?content=principals (accessed 1st December 2009).

[8] Peter Senge (2006, P. 140) calls structural tension, ‘creative tension’.

[9] Senge, P. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, (Revised and Updated Edition), London, Random House, pp. 140-143.

[10] Schein, E. H. (1980). Organizational Psychology, 3rdEdition, Englewood Cliffs, NJ., Prentice-Hall, P. 40.

[11] For example, a student may be very happy to get a part-time job washing cars while studying. However upon graduation washing cars for a living would be very disappointing for him or her.

[12] As a child we learn that we cannot jump off the roof and fly like a bird and cannot jump out of a moving car etc. The inner assumption of not being able to achieve our fantasies is a primal assumption designed to keep a person out of harm’s way.

[13] Fritz, R. (1991). “Creating”.

[14] This is something common in many great achievers in public life.

[15] Lykken, D. T. (2005). Mental Energy, Intelligence, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 321-335, O’Connor, P. J. (2006). Mental Energy: Assessing the Mood Dimension, Nutrition Reviews, Vol. 64, No. 7, pp. S7-S9.

[16] Emotional energy could be a primal defence against danger. For example, something strange has been seen or heard in the distance and the mind has an opportunity to consider the response to the potential sign of danger. There is a normal reflexive response to freeze and then consider what to do next. The response will be emotional rather than reasoned, as emotions are much quicker to generate than thoughts and reasoning.

[17] For a superb account of how our cognitive, emotional and physical systems function see chapter 5 of Michael A. Jawer and Marc S. Micozzi, The Spiritual Anatomy of Emotion.

[18] There are many definitions and descriptions of the concept of Qi. Qi is a concept describing our life-process, our bodily flow of energy that sustains our life. According to the principals of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Qi circulates around our body where metaphorically it could be viewed as a biological plasma that maintains our general functioning and health. However like emotional and mental energy Qi cannot be detected through any form of scientific instrumentation.

[19] A mood is a long lasting emotional state that is less intense that the emotions they are based on. Unlike emotions, moods are not necessarily triggered by crisis events. A mood will usually have a positive or negative feeling orientation, such as a good or bad mood.

[20] Rather than look at a situation and run through a series of potential options to find the optimum action, we tend to judge everyday things based on our emotions.

[21] Psychotic disorders are actually emotional disorders that arise through situational and social conflict dealing with issues of anxiety, low self esteem, feelings of hopelessness, resentment or persecution, etc.

[22] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, New York, Harper-Collins, P. 122.

[23] Lieberman, H. R. (2007). Cognitive methods for assessing mental energy, Nutrition Neuroscience, Vol. 10, No. 5-6, pp. 229-242.

[24] Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). “Creativity”, P. 345.

[25] Goldberg, W. A., Clark-Stewart, A. K., Rice, J. A. And Dellis, E. (2002). Emotional Energy as an Explanatory Construct for father’s Engagement with Their Infants, Parenting, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 379-408.

[26] Lykken, D. T. (2005). “Mental Energy”.

[27] Sinha, Y., Jain, U. C. and Pandey, J. (1980). Attribution of Causality to Poverty, Journal of Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 8, pp. 349-359.

[28] Lerner, M. J. and Miller, D. T. (2001). Just World Research and the Attributes Process – Looking Back and Ahead, Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 85., pp. 1030-1031, 1041-1042.

[29] Vick, S. G. (2002). Degrees of Belief: Subjective Probability and Engineering Judgment, Reston, VA., ASCE Press, P. 218.

[30] Burgman, M. (2005). Risks and Decisions for Conservation and Environmental Management, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, P. 89.

[31] Morgan, M. G. and Henrion, M. (1990). Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing with Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, P. 142.

[32] Taylor, S. E. and Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: a social psychological perspective on mental health, Psychological bulletin, Vol. 103, pp. 193-201.

[33] Alloy, L. B. and Abramson, L. Y. (1979). Judgment of contingency in depressed and non-depressed subjects: sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: general, Vol. 108, pp. 443-479.

[34] Mirels, H. L. (1980). The avowal of responsibility for good and bad outcomes: The effects of generalized self-serving biases, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 6, pp. 299-306.

[35] Weinstein, N. D. (1980). Unrealistic Optimism About Future Life Events, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 39, No. 5, pp. 806-820.

[36] Evans, D., Heuvelink, A., and Nette, D. (2003). The evolution of optimism: a multi-agent based model of adaptive bias in human judgment, Proceedings of the AISB ’03 Symposium on Scientific Methods for the Analysis of Agent-Environment Interaction, University of Wales, pp. 20-25.

[37] Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y. and Ross, L. (2002). The Bias Blind Spot: Perceptions of Bias in Self verses Others, PSPB, Vol. 28, No. 3, pp. 369-381.

[38] Kruglonski, A. W. (2001).Motivational Social Cognition: Enemies or a love story? International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, Vol. 1, No. 1., pp. 33-45.

[39] Freud, S. (Ed.). (1926). Inhibition, Symptoms and Anxiety. (1964 edition, Vol. 19), London, Hogarth Press.

[40] Both Petty and Cacioppo’s (1986) Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and Chaiken and Eagly’s (1989) Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM) assume where an individual’s motivation toward a topic is high they will engage in different cognitive processes in making judgments, than individuals whose motivation towards a topic is low.

[41] Kruglanski, A. W. and Webster, B. M. (1991). Group member’s reactions to opinion deviates and conformists at varying degrees of proximity to decision deadline and of environmental noise, Journal of Personality and Psychology, Vol. 61., pp. 212-225.

[42] Kruglonski, A. W. (2001), Motivational Social Cognition: Enemies or a love story? International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, Vol. 1, No. 1. P. 42.