Is there such thing as a Buddhist principled business?

A look at what a Buddhist orientated business might look like

Buddhist Dharma originated on the Indian Sub-continent with the birth of Siddhartha Gautama back in the 6th century BCE. Buddhism spread through South Asia, South East Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia, taking on many forms and variations, which include the Theravãda, Mahãyãna, and Vajrayãna traditions. Today Buddhism directly influences about 10% of the world’s population, although some practice a mix of Buddhism, and Taoism, that may even take on some Hindu influences.

Within the Abhidhamma Pitaka, the last of three parts to the Pali Cannon(the scriptures of Theravãda Buddhism) are a number of texts concerning psychology, philosophy and metaphysics. The Abhidhamma Pitaka describes the structure of the human mind and perception with amazing accuracy to the accepted views of modern neuro-science. The mind is described as a continual conscious process or experience in the metaphor of a ‘mindstream’ (something similar to phenomenological psychology) [61].

Within Buddhist philosophy, consciousness and metaphysics are combined in the concept of Pratîtyasamutpada or dependent origination. This is where reality is seen as an interdependent timeless universe of interrelated cause and effect. A human’s existence is interwoven with the existence of everything else and the existence of everything else is interwoven with the human’s existence in a mutually interdependent way. Because this concept is past, present and future, everything in the universe is only transient and has no real individual existence.

A person’s perception continually ebbs and flows on a daily basis with changes in intelligence, knowledge and understanding, based on the type of emotions one feels and their individual strength, pull and intensity. This process makes a person happy, sad, excited, hesitant or anxious about people, things and events around them. One may feel angry, greedy, jealous, trusting, lustful, and confused all in one day. More often than not, we are not aware of the influence of our feelings upon how we perceive things and behave, as this process is partly sub-conscious [62]. Feeling is what drives a person, whether it is to seek shelter and food, clothing and medical care, love and sex, career and comfort, etc. This is a very important concept because it is only our ability to free ourselves from attachment and delusion about our sense of self and values unconsciously placed on others, will we be able to see the world as it really is, rather than what we wish it to be. In fact our view of self and existence is created through our clinging and craving which blinds us to the reality of dependent origination [63]. The wheel of Samsara, or suffering through life is the heart of the First Noble Truth of Buddhism, that there is suffering. Although the wheel of Samsara may appear esoteric, the messages are straight forward without the divinity of mystic gods. This is the concept of Samsara was adopted into Buddhism with the metaphors of gods, afterlife, and rebirth, widely accepted during those times. Much of this mysticism has been added to Buddhism through the influence of various cultures and institutionalization over time [64].

Buddhism is about transcending delusions and the patterns and pathways we are locked into, so human perception is clear and unbiased. This makes Buddhism an ethical philosophy of life, rather than a religion in strict terms [65]. According to Buddhist Dharma (theology), desire is a major part of our motivation and psych. Buddhism sees mankind living in a deluded reality caused by infatuation, attachment [66] and clinging to desire for objects and permanence in the world as the source of all suffering. The pathway to wisdom [67] is found through understanding ‘The Four Noble Truths’ which are;

1. Our delusions of self-cause our suffering, 2. Suffering is a fact of life resulting from our attachment to what we desire, 3. If we extinguish our attachment, we reduce our suffering, and 4. By following the ‘Eightfold Path’ and developing wisdom, we can alleviate our suffering.

The first Noble Truth is about our habitual relationship and attachment to anguish and craving, and how we relate to the events within our life. Do we embrace our emotions and mistake them for reality? Do we realize the consequences of our actions? The third Noble truth is the ability to let go of our attachment allows us to see other realities, not based on the bias of the ego-centric ‘I’ or ‘me”. If we can achieve this freedom from our emotions, we can make decisions without just guessing about the potential consequences of our actions – a true wisdom.

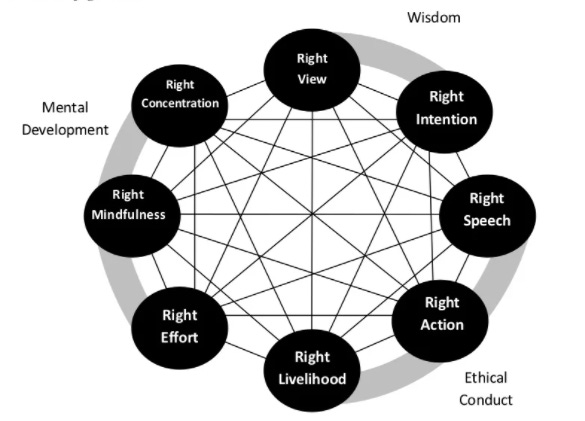

‘The Four Noble Truths’ can be seen as challenges to act rather than beliefs. Action as the fourth Nobel Truth espouses the practice of the ‘Eightfold Path’, which is a practical set of methods to let go of our attachment. The ‘Eightfold Path’ consists of right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, mindfulness and right concentration. Practice of the Eightfold Path may assist in raising consciousness to a completely non-dualistic view of subject and object. There is actually nothing spiritual or religious about the ‘The Four Noble Truths’ or ‘Eightfold Path’. The ‘Eightfold Path’ is about everything we do, a mode for being in this world. Such practice underpins the visions and ideas we develop. A depiction of the “Eightfold Path’ is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. A Depiction of the “Eightfold Path’

A brief description of each stage of the ‘Eightfold Path’ is below;

Right view is both the beginning and end of the path. Right view is about understanding the ‘Four Noble Truths’ and seeing true realities without the delusion of craving and attachment. With the Right view the see the imperfectness of our nature and that around us. We understand the Law of Karma [68] and dependent origination. Right view is the cognitive aspect of our wisdom or knowing, as our view of the world forms all intentions, thoughts and actions. It is an intuitive insight that all beings endure suffering and this can end with and understanding of the true nature of all things. Right view precipitates right thoughts and right actions.

Right intention is our mental energy that controls our actions – the ethical part of wisdom. Right intention is commitment to self development based upon our personal ethics. Without right intention our ethics are covered up by our emotions which overshadow our mental energy with emotional energy. Right intention involves resistance to desire, anger, aversion, cruelty to others, or aggression. Therefore, right intention is the source of our compassion.

Right speech is the first part of our ethical conduct within the ‘Eightfold Path’. Speech is considered very powerful and be as potent as action, therefore it is important to abstain from false speech, deceitfulness, slanderous speech, maliciousness, offensive or hurtful language to others, and idle chatter that lacks purpose. Right speech encourages a positive frame of telling the truth, speaking friendly, warm and gently, and only talking when necessary.

The second part of ethical conduct is Right action. Right action involves the body as a means of expression, and deeds that involve bodily actions. Poor action leads to ethical degeneration, while wholesome actions reinforce our sense of ethics. Right action is restraining oneself from harming other beings, especially the taking of life, taking what is not given, dishonesty, and sexual misconduct. In the positive frame Right action is about acting kindly to others, being compassionate, honest, respecting the belongings of others, and keeping sexual relationships harmless to others.

The third aspect of ethical conduct is Right livelihood. Right livelihood is about earning a living in a righteous way, where wealth is gained ethically, legally and peacefully. Dealing in weapons, dealing in living beings, i.e., raising animals for slaughter, the slave trade and prostitution, working in meat production and butchery, and selling intoxicants and poisons, as well as anything that violates Right speech and Right action should be avoided.

Right effort is the first aspect of mental development. This is a prerequisite for all the other elements along the path. Effort is an act of will which without, nothing can be achieved. Misguided effort leads one into delusion and negative Karma and confusion. Right effort depends upon our mental energy which can be positive producing self discipline, honesty, benevolence, and kindness, or negative producing desire, envy, aggression, and even violence. Right effort is necessary to prevent unwholesome occurrences, abandon unwholesome states that have already occurred, to arouse wholesome states that have not yet occurred, and maintain continuing wholesome states.

Right mindfulness is the preferred state of cognition. This is awareness that brings the ability to see things for what they really are – a high level of consciousness. Right mindfulness is both part of our perceptions and thoughts, to see beyond our stereotyped impressions and existing biases and patterning [69]. Through mindfulness one can control the way thoughts go and maintain wholesomeness. Four bases of mindfulness exist; contemplation of body, contemplation of feelings, contemplation of state of mind, and contemplation of phenomena.

The final principle of the ‘Eightfold Path’ is Right concentration. Right concentration refers to the development of focus in our consciousness. This can be enhanced through the practice of meditation.

In addition to the above Buddhist paradigm, other aspects of Dharma can also be developed into additional frames. These may include the concept of dependent origination which has influenced quantum and systems thinking, interpreting Samsara as organizational typologies in organizational development, and utilizing the concept of Karma in ethics and strategy.

There is very little evidence of direct influence of Buddhist Dharma upon business in Asia. Many studies mix Buddhist and Confucian philosophies which although bear some similarities, are also contrastingly different [70]. Although some cases are reported [71], the Buddhist business is more myth than reality. This is partly because there is very little consensus about what a Buddhist venture would actually be like (the author’s interpretation is only one possible interpretation). The only visible evidence is the belief and practice of a degenerated form of corrupted Buddhism, mixed with superstitious rituals, artefacts, ceremonies, giving donations to the temple for positive Karma, and praying to Bodhisatvta for wealth and prosperity.

However, Buddhist Dharma has influenced Western psychology significantly. The teachings of the Abhidhamma Pitaka have inspired and influenced many psychoanalysts and psychologists [72], including Carl Jung, Erich Fromm, Albert Ellis, Jon Kabat-Zinn and Marsha M. Linehan. There has been a great leap forward in humanitarian and transpersonal philosophical influence in therapy [73]. Dialogue between philosophy theorists and practitioners of East and West has led to mutually influential relationships between them [74]. This has led to new insights into therapies and new schools of thought on both sides [75]. Many of these practices are being used in modified forms for therapy today [76]. Aspects of Buddhist Dharma are also incorporated in the works of Western philosophers including Caroline A. F. Rhys David and Alan Watts.

Applying Buddhist philosophy to organization and management in “Western society” is also not new. Writers have focused upon the quantum analogies of Buddhism [77], ethics [78], and humanist views [79]. The wheel of Samsara provides insight that emotions play a major role in all organizations [80], where occidental organization theories have tended to ignore the role of emotion in organizations until quite recently [81].

The concepts of dependent origination through systems theory and a reframed ‘Eightfold Path’ is similar to many of the concepts within the learning organization. Peter Senge is the Director for Organizational Learning at the Sloan Business School at MIT in Boston. He was one of the high-profile academics during the 1990’s and propelled the concept of Learning Organization into the management vocabulary. Senge defines the learning organization “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together” [82]. Such organizations according to Senge will be able to face the rapidly changing environment with flexibility and adaptation, driven by peoples’ willingness and capacity to learn at all levels. However current organization structures and form are not conducive to learning and people although having great capacity to learn, do not have the tools needed [83].

Senge believes that people want to be part of something bigger than themselves to grow and this is where they have opportunities to ‘re-create’ themselves. The prevailing method of learning in organizations is adaptive learning focused on survival, but for a learning organization there must also be generative learning, organizational learning disabilities can be overcome. Generative learning requires a mastering of five disciplines;

· Systems thinking; seeing the world and events as a whole, where forces behind them are related. This helps us to see relationships and helps us to see how to change things effectively with minimum effort, i.e., to find leverage points in the system. This has a lot of similarities with the concepts of dependent origination.

· Personal mastery; the process of continually deepening and enriching our personal visions, the focusing of energies, developing patience and seeing reality objectively. Personal mastery could be considered a product of the ‘Eightfold Path’.

· Mental models; are unconscious metaphors of how we see things, which influence how we act. If we can understand how, we see things, we are in a better position to see reality more objectively. Mental models are about wisdom and right mindfulness.

· Building shared vision; to develop a shared picture which will create commitment, rather than just compliance by individuals. Building shared vision is about right intention, right action, right effort, and right concentration, and

· Team learning; is the ability of the group to rid themselves of their assumptions and begin to think together. This must be done openly without anyone trying to win. Team learning is about the journey that the ‘Eightfold path’ takes a community.

These disciplines can be focused towards seeing wholes, rather than parts, seeing people as active participants, rather than helpless reactors and to creating the future, rather than reacting to the past.

Senge and his team spent many years developing this process. However, companies found it extremely difficult to implement as managers were unwilling to give up power, management didn’t give enough flexibility and authority to staff, individuals weary about taking on the responsibility, managers and employees just simply didn’t have the skills and the process was undermined by organizational politics, something which is not directly tackled in Senge’s process. Learning organizations are fundamentally different from authoritarian organizations and it was beyond management to let go and make these radical changes. Learning organization is not a quick fix as many had assumed, but a daunting task requiring exploration of individual performance, personality and ambitions in life, something beyond many peoples’ willingness to make commitment. There are few organizations that resemble Senge’s model and while business wants to develop long term growth and stability, their focus is on enhancing brand recognition and status [84], intellectual capital and knowledge and product development and ensuring production and distribution efficiency [85], and solid financial returns [86]. There have been many suggestions that Senge’s model is just too idealistic and perhaps ahead of its time because of its revolutionary approach [87] and that it will take people to really make a commitment to organizational life in new ways. In 1994, Senge with his colleagues published the fieldbook [88] providing more ideas and suggestions about how to develop the process of learning organization.

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

References:

[61] The early concept of phenomenology was developed by G.W.L. Hegel, who was interested in exploring the phenomena of conscious experience. These concepts were further developed by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, later enlarged upon by numerous philosophers including Franz Brentano, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Max Scheler, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand and Emmanuel Levinas. Phenomenology looks at the consciousness as a process of experience rather as a static state. Consciousness is seen as a continual process where something is always in view, whether it be a perception of an object, event or fantasy. Therefore to consciousness it is not important whether the object is real or imaginary – the conscious intention exists of the object. In phenomenology the truth is what is intelligible based on one’s subjective opinion rather than physical reality. The perceived reality comes from the individual’s emotions, which are within the consciousness. The consciousness exists in the lifeworld, which in addition to the physical world includes all life experiences and memories. Some view the world as being completely transparent before the consciousness.

[62] Tashi Tsering, Geshe (2006). Buddhist Psychology: The Foundation of Buddhist Thought, Vol. 3, Somerville, MA., Wisdom Publications, P. 46.

[63] Dependent origination is a concept describing interrelatedness. It is represented on the other wheel of Samsara in the twelve states of ignorance, mental formation, consciousness, name and form, the six senses, contact, feeling, craving, clinging, becoming, birth and old age, and death. The state of our being and evolution is based on cause and effect. Through this journey our actions have consequences which bring recurring suffering, i.e., action brings suffering and suffering leads to action, in a reciprocal relationship of interdependence we are locked into. Through dependent origination we become locked into patterns like the metaphor of the channel of a stream being embedded and becoming a fixed feature of the geography of an area. This is becoming, a creation of our previous actions which makes up the elements of our personality.

[64] Batchelor, S., (1997), Buddhism without beliefs: A contemporary guide to awakening, New York, Penguin, P. 4.

[65] Watts, A, (1996). Buddhism the Religion of No-Religion: The edited transcripts, Boston, Turtle Publishing.

[66] Attachment in Buddhism is a much wider concept than attachment in psychotherapy where it is primarily concerned about infant/caregiver relationships in early life. Although there are many similarities, the two concepts should not be confused

[67] Wisdom in Buddhism can be interpreted as acceptance of Karma and conscious awareness of those actions that will bring us happiness and those that will bring us suffering and the understanding of the concept of non-duality, recognizing that there is no permanence.

[68] Karma is the law of cause and effect in relation to our mind, speech and actions, i.e., moral causation. New karma is continually generated through our ‘mindstream’ and is kept within us like a storage bank. Karma can be good or bad depending on the nature of the actions. Our stored karma determines how we perceive and respond to stimuli in the world. These are considered our natural or intuitive responses.

[69] Hunter (2012), op. cit. Vol. 1, pp. 22-23.

[70] Weber, J. (2009), Using Exemplary Business Practices to identify Buddhist and Confucian Ethical value Systems, Business and Society Review, Vol. 114, No. 4, pp. 511-540.

[71] Prayukvong, W., (Undated), A Buddhist Economic Approach to a Business Firm: A case Study, accessed at http://www.eco.ru.ac.th/eco/necon6/papers/g3/3.4.pdf (16th March 2012).

[72]Trungpa, C. (1975). Glimpses of Abhidharma: From a Seminar on Buddhist Psychology, Boston, M.A., Shambhala Publications, de Silva, P. (1991). Buddhist Psychology: A review of theory and practice, Current Psychology: Research and Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 236-254, Claxton, G. (1990), Meditation in Buddhist Psychology, In: West, M. A. (Ed,), The Psychology of Meditation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, Epstein, M. (1995) Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective, New York, Basic Books.

[73] Goleman, D. (2004). Destructive emotions and how we can overcome them: A dialogue with the Dalai Lama, London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[74] Safran, J. D. (2003). Psychoanalysis and Buddhism as cultural institutions, In: Safran, J. D. (Editor), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An unfolding dialogue, Boston, Wisdom Publications, pp. 1-34.

[75] Grossman, P, (2004). Mindfulness Practice: A unique Clinical Intervention for the Behavioral Sciences, In: Heidenreich, T., and Michalak, J., (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance in Psychotherapy, Berlin, DVTG Press, pp. 16-18, Safran, J. D. (2003). Psychoanalysis and Buddhism as cultural institutions, In: Safran, J. D. (Editor), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An unfolding dialogue, Boston, Wisdom Publications, pp. 1-34, Sherwood, P. M. (2005). Buddhist Psychology: Marriage of Eastern and Western Psychologies, www.sophiacollege.com/publications/Buudd%20pschoz.pdf, (accessed 20th October 2009).

[76] Epstein, M. (2001). Going on Being, New York, Broadway Books.

[77] Low, A., (1976), Zen and the Art of Creative Management, New York, Playboy Paperbacks.

[78] Field, L., (2007), Business and the Buddha: Doing well by doing good, Boston, Wisdom Publications.

[79] Larkin, G., (1999), Building a Business the Buddhist Way, Berkeley, Celestial Arts.

[80] Hunter, M. (2012), op. cit. Vol. 1, pp. 255-271.

[81] One of the first books on Emotions within organizations was: Fineman, S. (Ed.), (2000), Emotions in Organizations, London, Sage.

[82] Senge, P., (1990), The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization, New York, Doubleday, P. 3.

[83] Ibid. Ch. 2.

[84] Klein, N., (2001), No Logo, London, Flamingo.

[85] Leadbeater, C., (2000), Living on Thin Air: The New Economy, London, Penguin.

[86] Hutton, W., (1995), The State We’re In, London, Jonathan Cape.

[87] Van Maurik, J., (2001), Writers on Leadership, London, Penguin.

[88] Senge, P., Roberts, C., Ross, R., Smith, B. and Kleiner, A., (1994), The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization, London, Nicholas Brealey.

Yes for buddhist's principled lay buddhist's business, eg vegetarians foods supply and it restaurant, charity organization and nursing homes including transportation service, plantation, construction, etc adhering to the basic 5 precepts of the Buddha teachings. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Five_precepts