Even though this article was written in 2019, the issues are still relevant today.

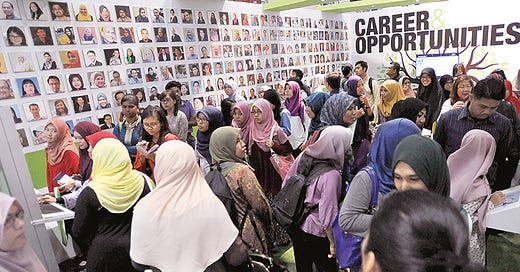

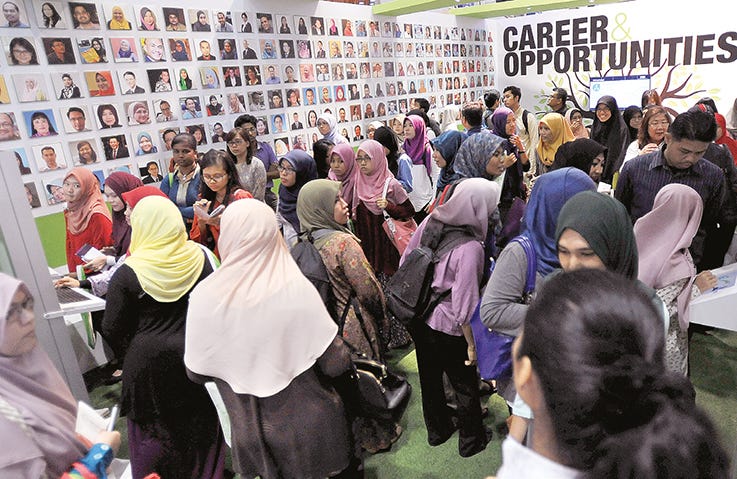

The youth unemployment rate in Malaysia, at 10.9 percent officially, is more than triple the national rate of 3.3 percent and has been gradually rising over the past decade, exacerbating the disgruntlement of a youth constituency that was instrumental in swinging the vote that brought the Pakatan Harapan coalition to power in the 2018 general election. Unemployed youth make up almost 60 percent of the 504,000 currently unemployed.

Then in opposition, Pakatan Harapan campaigned hard on youth-friendly policies with firm pledges to tackle youth unemployment. But after more than a year of unfulfilled promises like amending the Universities & Colleges Act to allow students to become involved in politics, disillusionment is increasing rapidly. A recent Merdeka Centre survey of voter satisfaction found that 42 percent, (53 percent among Malays) of the 20-30 years age group were either dissatisfied or angry with the Pakatan Harapan government.

Three distinct youth unemployment segments can be identified:

1. Graduate youth. The Ministry of Education reported that 57,000 of 173,000 of last year’s graduates remained jobless after looking for a job for six months.

2. Rural youth, those who principally remain at home with their parents and are not working, and

3. Urban youth, comprising non-graduates who are looking for employment in retail, administration, distribution, manufacturing, hospitality, or other service industries.

Graduates – Structural mismatch and over-supply

The prime reason for graduate youth unemployment is the mismatch of graduate qualifications with the country’s workforce needs. Of 1.47 million vacancies, 86.9 percent are for low skilled jobs. Only 4.7 percent of those advertised required any tertiary qualifications. Graduate unemployment was 9.6 percent or 204,000 at the end of 2108.

The Ministry of Education decides what courses universities offer rather than market forces. This is where the mismatches are coming from. Malaysian universities are currently overcapacity and producing too many graduates to what can be generally absorbed into domestic Malaysian workforce.

Rural Youth – The hidden segment

Rural youth unemployment has been endemic in Malaysia’s kampongs over the past decade. Asia Sentinel visited Northern Malaysia and the East Coast to speak to civil servants and police officers on the ground about the problem. It is estimated that rural youth unemployment could be as high 75-90,000. This is statistically uncounted as many still live with their families and haven’t claimed they are actively looking for work.

This group is primarily only educated to secondary school, with many not finishing. According to civil servants on the ground, rural youths don’t feel motivated to travel to towns to take up jobs that pay low wages. Many can only speak Malay, have no skills and are not self-disciplined. In addition, many non-skilled jobs are taken by foreign workers which makes these jobs socially unappealing to local youths. Serving people isn’t natural to this group and those who try to work in a restaurant or shop usually only last a few days and give up.

According to police officers on the ground, drug taking is epidemic. Youths usually start off smoking the local narcotic leaves of the Ketum tree. Many progress to other drugs, which they have to buy. This has led to a dramatic increase in crime, including house break-ins, motorbike thefts, and shoplifting. Some even rob their parents and siblings to pay for their drug habits, often holding their parents at knife-point. These crimes are often hidden from the system where police prefer to work on solutions with the parents rather than going through the formal legal processes.

Youths in the kampungs are often idle, bored, lose self-esteem, and develop apathy towards life in general. This feeling of hopelessness often leads to bouts of depression that are never diagnosed or treated. The few employers in rural areas prefer older employees who are perceived to be more responsible and reliable.

Urban Youth – Another hidden segment

This segment is also underreported as many youths are also still living with their parents and not actively looking for work. The past couple of years have seen job redundancies where younger workers are being laid off before more senior workers. This added more than 21,000 to unemployment levels last year.

A Job Street survey found the 58 percent are choosy about what job they do or company they work for, 58 percent are considered of poor character, attitude or personality, 52 percent have a poor command of English, 49 percent have poor communication skills, and 66 percent have unrealistic salary expectations.

Tolerance within Malay culture has decreased towards jobs within the hotel, hospitality, and tourism industries, putting a massive block on employment prospects. A generation ago, these three sectors were considered acceptable. Today these jobs are considered dirty, low and dangerous. Serving alcohol to others is now almost taboo in Malay culture. Consequently, the hotel, hospitality and tourism industries prefer employing foreign workers to avoid cultural and religious issues.

Foreign investment coming into Malaysia tends to require low and unskilled workers. These jobs offer low salaries and there is a need to leave home to work, which doesn’t appeal to local youth. FDI in Malaysia is creating jobs for foreign rather than local workers.

Government Inactivity

One of the major problems in tackling youth unemployment is that the government hasn’t analysed the root causes of youth unemployment, which is also grossly understated. Statistical definitions which don’t count people who are not actively looking for work is hiding additional youth unemployment in the urban areas and the rural heartlands. These hidden segments may add as much as another 35-50 percent to youth unemployment figures.

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad during parliamentary question time last July said that the “unemployment rate among youth between 15 and 24 years old is a normal phenomenon faced by developing and developed nations….(where) …This group is said to be in a transition process between a learning environment and the realities of the employment market.”

This gives the impression the government isn’t really serious about the problem, especially with the ideas to tackle the problem coming from the 28-year-old Youth and Sports Minister Syed Saddiq. The minister opposed raising the retirement age from 60 to 65 on the grounds that older workers are taking potential jobs from younger unemployed people. Syed Saddiq also suggested that the Indonesian motorcycle hailing service GoJek could be introduced into Malaysia to create jobs. This has been met with fierce criticism because of the danger of motorcycles on Malaysian roads and competition GoJek would give existing taxi drivers.

Unemployed people who have never been in the workplace are not covered by the EIS unemployment insurance scheme. This is forcing youths to stay at home without being able to make any financial contribution, straining households financially.

Education System problems

The root cause of graduate unemployment is the mismatch and surplus of graduates to what industry really needs. What is being taught in universities needs urgent review. In addition, there are just too many university places available for the needs of the local workforce.

Technical and Vocational Educational Training (TVET) needs urgent review. There should be more focus on providing practical skills and trades through certificates, rather than diplomas and degrees. These programs have to outreach to those who need them in the rural heartlands, rather than being centralised in large city and town campuses.

Entrepreneurship has been seen as the ‘magic bullet’ to ease youth unemployment. This is a misnomer. Entrepreneurship is about developing new startups based on a source of innovation, which is very risky. Fewer than one in 10 startups survive for more than five years. The emphasis needs to be placed on teaching youth basic trades to provide a small income, and teach those a little more ambitious the concepts of small business, rather than entrepreneurship.

In the Malay heartlands, youth may be much more attracted to micro-businesses that fit into their lifestyle than a business or job they must fit into. Rather than educational institutions focusing on equipping youth with industry 4.0 skills, should focus on turning kampungs into sustainable socio-eco-systems that assists youth in enriching their lives.

Under such a premise, the whole youth training pedagogy needs to be completely reframed to make an impact on youth unemployment in the rural heartlands.

The Achilles Heel

World Bank comparative youth unemployment puts Malaysia as the second highest to Indonesia in the region. With the hidden unemployment segments added in, Malaysian youth unemployment is probably more like 15-18 percent.

A whole generation of economically and socially disenfranchised youth is growing up. This will have its consequences. This is the legacy of successive governments which have blindly accepted foreign investment projects that employ foreign rather than local workers. This is the legacy of central planning in public education. Foreign workers have kept wages down and created a social stigma for young locals taking up unskilled work. The enthusiasm of the government to build so many universities has done a great disservice to vocational education, which is considered the last educational choice by Malaysians.

Education needs a massive rethink. It needs to be radically skewed towards vocational training. Not the large polytechnics, but small community centres that bring informal skills-based training to those who need it.

The Pakatan Harapan Government has been found wanting in reform. Now we are finding that it’s also lacking in fundamental economic management.

The major issue for the government today is youth unemployment. This is the constituency that brought Pakatan Harapan into government and this will be the constituency that also boots them out of government next election. The disappearance and silence of Pakatan Harapan youth leaders since the election is symbolic of the problem. If youth unemployment stays as it is, then prepare for a possible change of government next election.

Originally published in the Asia Sentinel 11th September 2019

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox: