Malaysia’s Sarexit Nightmare (updated)

Malaysia is set to continue as a nation of convenience. Asia Sentinel 24th September 2019

“Malay supremacists won’t rest until they take full control of both Sabah and Sarawak” – Dennis Ignatius

Could there be a Sarexit movement in store for the East Malaysia states of Sabah and Sarawak? The movement is in its infancy, its current support base composed of urban non-Muslim professional and business people, numbering in the hundreds.

Although many more are sympathetic, they are apprehensive about the cause. The movement hasn’t reached the rural areas and longhouses yet, as most there are still politically disinterested and rely on their children to advise them about political matters. In contrast, the Sabah secession rhetoric has been going on for years by a small group of professionals and politicians, and although it has many sympathizers hasn’t grown into a popular movement because of fear.

But Sabah and Sarawak have been the victims of what many of their citizens consider to be festering injustices that stretch clear back to the 1960s, when they were incorporated first into the Federated Malay States upon British colonial withdrawal and later into what became Malaysia when Tunku Abdul Rahman, the country’s founding leader, kicked Singapore and Lee Kuan Yew out of the federation.

(Former) Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad, aware of the tiny but potent thoughts of secession, recently threatened to use the Sedition Act against them, further threatening the use of Section 121 of the Penal Code, which carried the possibility of the death penalty for waging war against the Yang di-Pertuan Agong, or king. The writer has been informed that Special Branch has infiltrated the Sarexit movement and will arrest key activists, if they believe it necessary.

Where to Malaysia?

Current symbolism and narratives are not very helpful in promoting any sense of national integration. The federal government lost the plot on national unity by promoting the celebration of Merdeka Day (Malayan independence) on 31st August on the Peninsula over Malaysia Day which remembers the formation of Malaysia. Malaysian Merdeka Day is meaningless to Sabahans and Sarawakians. A day in common for the whole nation is needed. Some in Sabah and Sarawak view 16th September as Occupation Day as there was no referendum on the entry of Sabah and Sarawak into Malaysia.

According to Section 32 (3) of the Malaysian Constitution, no Sabahan or Sarawakian is eligible to hold the office of Malaysia’s head of state, making the two states symbolically inferior to the other states of the Federation. The banning of the use of the word Allah by non-Muslims(just recently overturned by the courts), where Christians in Sarawak have been using the word for more than 150 years discriminates against minority cultural and religious practices. The banning of Muslims and Non-Muslims praying together is an affront to the culture of Sarawak and Sabah. The Perlis Mufti Mohd Zainul Abidin’s comments that Malaysia must have a dominant race is contrary to the concept of national integration.

The continuation of Sabah and Sarawak’s immigration procedures for Malaysians arriving from the Peninsula indicates that the states are resisting national integration, (although, many locals believe it is their state’s right). Condescending attitudes of federal civil servants while working with their local counterparts in Sabah and Sarawak shows an insulting arrogance, (coming from Putra Jaya), where many feel they are colonized. (Former) Finance Minister Lim Guan Eng’s comments about delaying the return of monies owing to Sabah is an indication that Sabah and Sarawak are only a secondary consideration to Putra Jaya. Finally, the continual rhetoric that “Sabah is for Sabahans”, and “Sarawak is for Sarawakians” also goes against the spirit of shared nationhood.

The Constitutional Amendment Bill tabled in Federal Parliament by the PH Government in 2019 to restore Sabah and Sarawak’s special status in Malaysia was a ploy to get GPS to either abstain or vote against the amendments. The GPS abstention on the amendment will be used against them on the hustings during the coming election campaign.

Two Semenanjung parties, the Dap and PKR have been slowly increasing influence within Sarawak. Their influence is strong around the townships of Sarawak, holding 12 and 3 state constituencies respectively. In the 2018 general election, the DAP won 6 and PKR won 4 federal seats. PKR’s representation was increased by two with the defection of two independents. This is almost one-third of Sarawak’s federal representation in federal parliament. However, the split of the Azmin Ali faction from PKR to Bersatu, has taken 5 seats way. Bersatu has pledged to work with GPS in the coming state election, due in Ausgust 2021, but it’s not known in what form. The current GPS leadership has pledged that it will run its own candidates in all constituencies. Three cornered fights between GPS, PKR and Bersatu, should favour the GPS.

Tunku Abdul Rahman’s May 1961 announcement of the Federation of Malaysia, the result of many years of proposals, negotiations, and re-negotiations, was a vision by a Malay anglophile elite to form a greater Malaya to compete with Sukarno’s idea of an Indonesia Raya.

Reception in North Borneo and Sarawak was mixed, as many were comfortable with the British as their protector. There was also a view that North Borneo, Brunei, and Sarawak, which at the time had a population of fewer than one million, would not be economically viable states on their own.

Singapore as part of the merger gave the leaders of North Borneo and Sarawak confidence to join the federation. Tunku Abdul Rahman was concerned that without North Borneo and Sarawak, the added Chinese population from Singapore who would dominate the new federation.

The British saw a merger between Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei (which pulled out at the last minute), as a solution for their smaller colonies and dependencies. A quick federation would also comply with the UN decolonization process. Geopolitically, a federation of Malaysia with Singapore involved would prevent a potential Asian Cuba developing, as communist agitation was steadily rising on the island in the midst of the Cold War.

Federal government Takes Dominance

The events leading to the expulsion of Singapore in 1965 showed a recurring theme that would continue to dominate political interrelationships within the Malaysian federation for years to come.

Disagreements between the PAP of Singapore and UMNO, the dominant party of the national governing coalition, were deeply ideological over the issue of special rights for Malays versus a ‘Malaysian Malaysia’. It was also about the clash of two strong charismatic figures Tunku Abdul Rahman and Lee Kuan Yew. In August 1965 at the Tunku’s bequest, Singapore was expelled from the federation.

That was the beginning of the path towards a Malay Malaysia.

Article 153 of the Malaysian Constitution gave special rights to Malays and other indigenous peoples, and Article 3 (1) stating Islam as the official religion now became a powerful influence over KL-Sabah-Sarawak relations and events over the next 54 years.

The federal government’s incremental power-grabbing and the implementation of positive discrimination towards Malay-Muslim groups led to dissatisfaction within Sabah and Sarawak.

The greatest point of contention between Sabah, Sarawak and the federal government was the way the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63) has been overridden by various means. The MA63 had a number of provisions which ensured the autonomy of Sabah and Sarawak on a number of issues covered in what is known as the 18 and 20 points agreements. These areas included immigration, education, budgetary payments, religion, language, representation in federal parliament, and citizenship.

The federal government has often brushed aside the constitution in pursuit of its own interests. 60 percent of Malaysia’s oil and gas resources lay off the coast of Sabah and Sarawak. The constitutionally questionable Petroleum Development Act (1974) took away the rights of the states to their own oil reserves. In addition, the federal government changed state territorial waters from 12 miles to 3 miles unilaterally in 2012, which prevented states exploiting their own oil resources. The Sarawak Government has been challenging the sole right of Petronas to develop oil off the coast of the state through the court system for years.

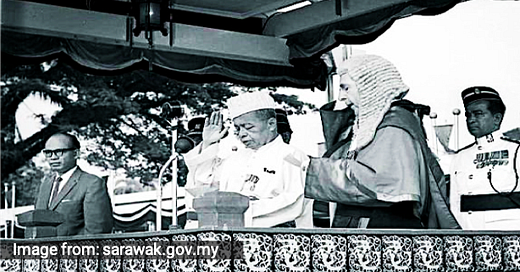

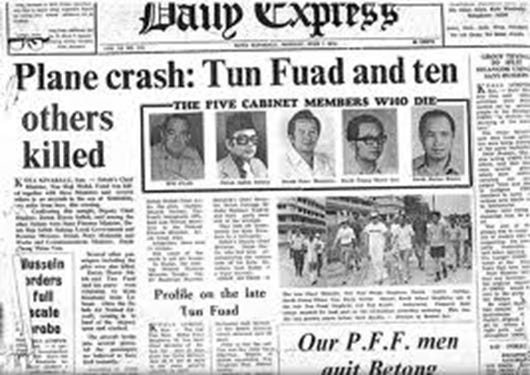

Mysterious events have also aided the federal government. In 1976, after negotiating a 20 percent oil royalty with then Finance Minister Tengku Razaleigh, then Sabah Chief Minister Tun Fuad Stephens was killed involved in a plane crash while on the way back to Kota Kinabalu with five of his state ministers. The new Sabah Chief Minister Harris Salleh, known for his pro-UMNO stance, agreed on a 5 percent royalty, rather than the 20 percent Tun Fuad had negotiated.

Tun Fuad: Will we ever know the truth?

Harris Salleh while Chief Minister of Sabah also ceded the sovereignty of Labuan to the federal government in 1984. The transfer was on the basis of Sabah making a contribution to national integration. Harris was also a major landowner on the island and the transfer of Labuan received a very small compensation package compared to the transfer of Kuala Lumpur from Selangor to the federal government years earlier. The loss of Labuan’s sovereignty to the national government has been a contentious issue in Sabah for many years.

UMNO took advantage of political infighting within Sabah to directly enter into state politics. Through elections and defections, UMNO was successful in forming coalition governments from 1995 to the last federal election, doing away with the chief minister rotation agreement with indigenous Sabah parties. The Sabah Heritage Party (WARISAN) part of Pakatan Harapan won over the state after six parliamentary members crossed over from the BN, in 2018. In the 2020 state election Bersatu, entering Sabah politics took 11 seats and Hijiji Noor is now Chief Minister.

The federal government has also changed Sabah’s population demographics, creating a Muslim majority in the state where Muslim dominated parties like UMNO and WARISAN could dominate local politics.

Since the 1960s Sabah’s population has increased by 400 percent, through what was dubbed project IC. Muslims have gone from being a minority to a majority group. Native groups like the Kadazan-Dusun which once dominated Sabah politics two decades ago have become a small minority, the subject of anger, criticism and even a Royal Commission without being redressed. There is now great concern with the new plan by Pakatan Harapan and WARISAN to give temporary documents to 600,000 illegal immigrants. The federal government and its local collaborators are accused of the theft of an entire country from its people by bringing in masses of immigrants.

Sarawak has been traditionally insulated from political intrusions from Peninsula Malaysia. However, Muhyiddin taking over Bersatu from Mahathir is intent on increasing the party’s foothold in Sarawak. Bersatu is currently setting up a branch network throughout Sarawak.

At the time, former prime minister Mahathir’s urge to Sarawakians to change the state government during his trip to Kuching on Malaysia Day was a battle cry that unnerved local politicians.

The federal government is setting up a rival village security network to the state-controlled Village Security and Development Committee (JKKK) in Sarawak. The new federal controlled Village Community Management Councils (MPKK) will operate deep inside rural areas which are political strongholds of the GPS. This is expected to have a very positive political impact in favor of Pakatan Harapan.

Betrayal of Their Own Cause

Sabah and Sarawak politicians haven’t always acted in the best interests of their own states. The Pakatan Rakyat government earlier this year attempted to put through a constitutional amendment to reverse the 1976 Constitutional amendment that took away Sabah and Sarawak’s special status, ranking them equally with the rest of the states in the federation. Sarawak’s GPS with 18 MPs abstained from voting, on the premise the amendment was only cosmetic, thus the two-thirds majority needed to pass the amendment was not achieved.

Sabah and Sarawak’s loss of status as a region within Malaysia has been an issue of contention for years. However, back in 1976 when the amendment to downgrade Sabah and Sarawak’s status was put to a vote, all Sabah and Sarawak MPs, except for four abstentions, voted to downgrade Sabah and Sarawak’s status.

1st Infantry Division, Kuching: You can check out, but never leave

Sarawak has its own form of ‘Ketuanan Melayu’. The Malay and Malanu groups are favored in the civil service over other indigenous groups. The Dayaks feel they have been divided and oppressed. In Sabah, there is ‘pro-Islam’ discrimination within the civil service. In 1973, then Chief Minister Mustapha Harun pushed through constitutional amendments to declare Islam as the official state religion, even though it was a minority religion at the time. Discrimination between Muslim Bumiputeras and non-Muslim Bumiputras has made non-Muslim Bumiputeras feel like second class citizens.

Stories of corruption and exploitation by both Sabah and Sarawak politicians are rife. There are many cases where politicians have put their self-interest first, and most political leaders who have served in government have accumulated wealth beyond their means. Patronage politics has made party cadres rich while their local communities have remained stagnant through lack of development. In addition, greedy bureaucrats hijack funds for development projects aimed at elevating poverty, keeping the rural areas undeveloped. Some see the federal government as a source of funds, which can be easily embezzled at the state level.

Probably the biggest weakness is the lack of unity between Sabah and Sarawak politically. Borneo nationalist politician Jeffrey Kitingan, an opposition leader in Sabah is regularly denied entry into Sarawak to hold political meetings about issues regarding Sabah and Sarawak within the federation of Malaysia. The lack of unity between Sabah and Sarawak gives Putra Jaya the upper hand.

Sabah and Sarawak were dealt a losing hand in 1963. Their power within the Federation of Malaysia greatly diminished with the retreat of Lee Kuan Yew and Singapore in 1965. Since then, the relationship has been of a transactional nature.

There is no grand vision of Malaysia other than the racist Ketuanan Melayu narratives which PAS leader Abdul Hadi Awang displayed after Malaysia Day celebrations in Sarawak. Ketuanan Melayu has defeated a Malaysian Malaysia which says goodbye to a truly inclusive nationhood. It’s the political elites who have been calling the shots, where peoples aspirations aren’t being heard. Malaysia is set to continue as a nation of convenience.