Mid Life Crisis and Transition

Transition and the Propensity to Embark Upon Entrepreneurship

Through the passage of life, people go through periods of regret, remorse, and depression about their achievements and existence. Economic conditions over the last 40 years have challenged the concept of traditional employment. Today secure jobs and long-term employment is less common than in the immediate post war and industrial development years (Bridges 1980). Downsizing, retrenchments, layoffs and bankruptcies are more common than ever before, creating trauma crisis and a vacuum in peoples’ lives.

People develop their own self-concept through their careers (Super et. al. 1996). Working is a form of self-expression which brings satisfaction, happiness, frustration and stress in a person’s life. A person’s career is an important anchor in their life, providing the basis of their own self-identity. People express who they are through their skills, competencies, position, status and values. This career anchor is an important sphere of influence on a person’s choices and decisions (Schein 1978, P. 125).

Abrupt career termination, job dissatisfaction, remorse about “what one has failed to achieve” in a person’s life leads to a “personal crisis” and as a consequence, a transition is required[1]. According to Erikson (1968), a person also goes through a number of stages during their life where their identity, achievements and self-worth are questioned. These periods whether caused by external trauma or internal self-doubt and questioning lead to very strong emotional states challenging a person’s reason and meaning of existence.

Personal crisis has its beginnings in adolescence where a career choice was made, that was not to a person’s liking. They wanted to please their parents and fulfill their father’s unmet dreams by proxy. They had taken on their father’s values in their early years without really questioning whether these values are consistent with their own self-identity. In later adult life a person realizes the mismatch between their own ideals and what they are actually doing (Levison 1978). This comes as a shock, as they realize time is running out and instead of doing something that has meaning to them, they are trapped in a job that brings dissatisfaction and resentment. Change is very difficult because of financial and family commitments; they are a prisoner of their own making, locked in the treadmill of life that is taking them nowhere. This can create great anxiety, depression and panic.

Up to middle age people usually focus on the external aspects of life which attracts the trimmings of career success in way of career, position, prestige, status and a reasonable standard of living for all those around them. However, this is usually at the cost of the inside which is empty and neglected. Life has little meaning or emotional identity. His sacrifice of the inner self for the external world has been a costly one and a sense of grief sets in[2]. This realization can spring a set of behavioral changes as defence mechanisms against grief. This may be hostility towards his wife and children and in extreme cases result in separation and divorce. One response is to try and return to their youth and buy a sports car and take up new interests as a way to deny their emptiness.

Another reaction to the feeling of emptiness is the creation of fantasies and daydreams to help a person escape any inner feelings of depression. Melbourne psychologist Dr. Peter O’Conner (1981) found a number of recurring themes in these fantasies. Each of these fantasies represent inner struggles, represented as “if only I” aspirations. Each fantasy may provide some hints of how an individual can solve them, if the underlying needs can be seen.

The Farmer Fantasy is where a person visions himself controlling a farming domain where he exists with the rhythm of nature and produces crops with his own hands. There is a yearning for some feeling of integration with the land with the life as a farmer, owning, living and working the land. This fantasy represents a desire to go back to natural simplicity where satisfaction comes from producing things with his own two hands. Contrary to the hard work a farm demands this fantasy is also seen as an escape or freedom from the perceived shackled present life. The farm fantasy can also be seen as a seeking of purity and morality that has been missing. The farmer fantasy according to O’Conner (1981, P. 60) is the most common of all the fantasies.

The Nurseryman Fantasy is similar to the farmer fantasy with a greater emphasis on creation, growth and nurturing. This fantasy relates to man’s need to promote the growth of living things and escape the harsh realities of everyday life, where there are many demands upon him. He has worked hard to provide things for himself and his family in his earlier life at the cost of fulfilling his inner needs. This fantasy is a wish for inner growth, which has been lacking. There is also a need for self-care, intimacy and nurturing. Once these needs are realized, a person can change their lifestyle to seek what is needed. This fantasy is common in professional people.

The Helper Fantasy is about wanting to help others in some form of social work. This desire often comes after years of sacrificing the wellbeing of their family while in the pursuit of material wealth. Although the desire to help others is genuine, unconsciously this is a way of paying reparations for the neglect of their family in the past. A little deeper there may be a yearning for a relationship where they can care for and be cared for by someone. Just like the nurseryman, adjustments to lifestyle can be made to allow more time for relationships. Those who don’t find intimacy go on to undertake some social work. This fantasy is common in self-made, high energy, and successful people.

The Writer (or creative) Fantasy is about having the opportunity to be creative in some way. This could be the desire to write a novel, become a sculptor, a musician, a painter, potter or other creative activity. There may be a yearning to create some great piece of creative work, if only they could devote all their time to this activity. They see this as the key to ridding themselves of their despair and unhappiness. This fantasy tends to appear in intellectuals who have ignored the spontaneous and irrational side of themselves. So, this fantasy is about rebalancing oneself so that there is time to just ‘be oneself making sandcastles by the sea”. People are sometimes prevented from being themselves out of fear their behavior will not fit into the view that they believe people have of them. They may also fear failure which prevents them from picking up a brush, guitar or spade. This fear is denying their personal growth and psychic balance as a human being, keeping them out of touch with their creative and emotional side.

The Dropping-out Fantasy is a way of perceived escapism from grieving. This is quite a common reaction where simply dropping out is a form of regression to adolescence where one just runs away from the problem to make it go away. This fantasy may be symbolized by wanting to live on an island, a mountain, backpack through Asia or go into the outback of Australia, etc. Dropping out is about trying to find one’s misspent youth again, but any relief will only be temporary as the crisis will only catch up with the person again sometime in the near future.

If the dropping out fantasy is reframed from dropping out from something to dropping into something, the process can be a constructive one. A complete reassessment of goals and priorities, seeing what their real identity could be, may lead to doing something like opening a motorbike tour operation through the Himalayas, a scuba diving tour in the Great Barrier Reef or Andaman Sea, etc. Such a change may carry considerable risk but at the same time be something that the person always wanted to do, and thus be considered a move forward.

These fantasies can all be seen as typologies not too dissimilar to Jung’s archetype personalities. They are about what we aspire to be. There may be small cultural variations, but the fantasies represent some yearning or desire for change. Failure to change will lead to inertia of failure and emotional death. The feeling of ‘time running out’ becomes an excuse for doing nothing, most likely leading to inner anger and disappear and eventual bitterness for the rest of their lives. However, many see the rest of their life as an opportunity and resurrect themselves as the ‘hero’ that they once aspired to be. They battle with their own logic and rationality, where often rationality prevents the fulfillment of aspirations dismissing them as silly. There may be a fear of letting their emotions take over, thus transforming them into a realm that they have never experienced and thus fear. They deny their inner self.

If this is overcome, there will be change in existing relationships, the taking up of new activities or the commencement of self-employment with a sense of spiritual guidance influencing their future path. Therefore, it is not uncommon to see people changing jobs in their late thirties and early forties. Thus, the chosen activities, whether it is a new job, a desired business activity or some form of social entrepreneurship should more closely reflect their skills, competencies and aspirations than what they were doing before their crisis. However, taking up new activities and keeping oneself busy with a new hobby or venture will not solve this crisis if their fundamental fear is not faced and challenged. The inner world will remain empty and void with a feeling of continual regret and emptiness.

In these cases, opportunity does not come completely from perception of the external environment but is also part of one’s inner psych and suppressed self. To them any opportunity and subsequent exploitation becomes a persona of how they want to see themselves.

Women encounter their personnel crisis differently to men in many respects. A woman’s early work life is basically concerned with looking after the needs of others at their own expense. After a number of years of having to balance work, childcare and family life, women look for new challenges in life and will move on from their existing careers if it is not meeting their needs (Marshall 1994). Women want to spend more time on relationships that are important to them and seek activities that reflect their own true values (Borysenko 1996).

Women during midlife appear to adopt new cognitive perspectives about their views on family, career progress and responsibilities (Borysenko 1996). This cognitive shift usually provides a new positive frame on things where success is defined in new ways[3]. Women tend to develop a more focused holistic perspective about their life’s goals as they see there is no time to waste after their children have grown up and become independent and their own parents have aged (Gordon and Whelan 1998). Women see midlife as an opportunity to become involved in the world and want to make their contribution. As child care is no longer an issue, they seek to pursue both intellectual and financially rewarding challenges. Women look for challenge, the chance to live up to their true talents and abilities, which can lead to radical career change midlife. Within this frame opportunity and its exploitation becomes an expression of talents, abilities and aspirations as they would like to see themselves.

The phenomenon of personal crisis is not restricted to midlife. Situational changes will influence people to react and respond to newly perceived circumstances (Collin 1990). Crisis can occur at anytime during life, particularly when some form of trauma occurs. Trauma can occur through retrenchment or injury. Trauma may also be the result of a slow build up of job stress, career burnout, increasing or decreasing family responsibilities, a desire for control over one’s destiny, or lack of challenge in a person’s job. This may trigger changes in work and life values, which lead people to question and re-evaluate their life decisions, behaviors (Kanchier & Unruh 1989) and careers (Doering et. al. 1983), according to these new values.

Change can also occur due to a number of other factors. During a career a person may feel that they have reached a plateau where they have mastered their current job (Hall 2002, P. 122). This can lead to the questioning of a present work situation (Leong & Boyle 1997) where greater challenges are sought. Many people realize that they are looking for job achievement rather than job advancement (Zabusky & Barley 1996). There may be some realization that salary, position, status and prestige may be at the expense of their values and psychological needs, leading to a re-evaluation about their own self-concept and beliefs about themselves (Fiske & Taylor 1991). This may lead to a shock which proves either positive or negative. They may see themselves as how others see them which violate their own sense of basic values, leading to shock and confusion. Consequently, change becomes necessary to pursue their career goals according to their newly found values, rather than external measures of success. This may result in a want to fulfill a dream, gain control of their working life, autonomy, quality of work-life, flexibility, or work within a specific ethical framework of prime importance in their life. People may simply want to revive passion in their work. These feelings and wants are conscious rather than the unconscious fears that occur through a midlife personal crisis. People see change as a ‘spiritual response’ to what they perceive outside and feel within (Gibbs 2005). Factors triggering transition are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Factors Triggering Transition.

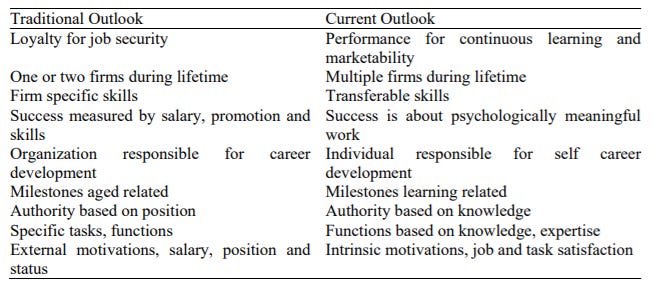

Table 1. Traditional and Current Outlooks towards Career and transition.

There has been a rise in job mobility in recent years due to financial need to continue working (Mirvis & Hall 1996) and a decrease of loyalty to organizations (Bridges 1994). People are staying longer in the workforce. The growing importance of professional social networks is also adding to increased job mobility and options of self-employment (Saxenian 1996). High self-confidence from a feeling of self-mastery and strong social networks tends to make perceived market opportunities seem more viable to a person, leading to high rates of self-employment in post-industrial societies. Consequently, contemporary outlooks about career differ greatly from more traditionally accepted outlooks over the last decades as shown in Table 1.

Originally published in the International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship, Vol. 1, Issue 2, June 2011, 237-244

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

Notes and References:

Borysenko, J. (1996). A Women’s Book of Life: The Biology, Psychology, and Spirituality of the Feminine Life Cycle, New York, Riverhead Books.

Bridges, W. (1980).Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes, Reading, MA., Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Collin, A. (1990). Mid-life career change research, In Young, R. A. and Borgen, W. A. (Eds.), Methodological approaches to the study of career, New York, Praeger Publishers, pp. 197-220.

Doering, M., Rhodes, S. R. and Schuster, M. (1983). The Aging Worker: Research and Recommendations, Beverly Hills, Sage Publications.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis, New York, Norton.

Fiske, S. T. and Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social Cognition, New York, McGraw-Hill.

Gibbs, N. (2005). Midlife Crisis? Bring it on!, Time, Vol. 165, No. 20, May 16, pp. 52-60, 63.

Gordon, J. R. and Whelan, K. S. (1998). Successful professional women in midlife: How organizations can more effectively understand and respond to the challenges, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 8-24.

Hall, D. T. (2002). Careers in and out of Organizations, Thousand Oaks, CA., sage Publications.

Kanchier, C. and Unruh, W. R. (1989). Factors influencing career change, International Journal for the advancement of counseling, Vol. 12, pp. 309-321.

Leong, F.T. L. and Boyle, K. A. (1997). An individual differences and approach to midlife career adjustment: An exploratory study, In: Lachman, M. E. and James, J. B. (Eds), Multiple Paths of Mid-Life Development, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, pp. 411-451.

Levison, D. (1978). The Season’s of a Man’s Life, New York, Knopf.

Marshall, J. (1994). Why women leave senior management jobs, In: Tanton, M, (Editor). Women in Management: A developing presence, London, Routledge, pp. 185-202.

O’Conner, P. (1981). Understanding the Mid-Life Crisis, Sydney, Sun Australia.

Schein, E. H. (1978). Career Dynamics, Reading, MA., Addison-Wesley.

Super, D., Savickas, M. L. and Super, C. M. (1996). The life-span, life-space approach to careers, In: Brown, D. and Brooks, L. (Eds.), Career Choice and Development, 3rd Edition, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, pp. 121-178.

Zabusky, S. E. and Barley, S. R. (1996). Refining success: ethnographic observations on the careers of technicians, In: Osterman, P. (Ed.), Broken Ladders, New York, Oxford University Press, pp. 185-214.

[1]Other trauma like a death of a close loved one in the family, or an event or tragedy will also bring about a crisis where transition or “moving on” is eventually required after grief and mourning.

[2] Although grief is an emotion for the loss of someone or something, the feeling of emotional emptiness and that life is coming to an end can trigger grief.

[3] For example, women realize the political realities and the ‘glass ceiling’ that exists, preventing any further promotion in their existing career. They see politics as de-motivating, energy wasting and eventually destructive, so opt for new challenges in different walks of life.