Online media will be the major battleground for GE15

Making sense of Malaysia’s online media portals

Online media plays a very important role in Malaysian politics. Until the advent of the internet the Rakyat (people) depended upon government owned and controlled media via television, radio, and print. Opposition politicians and alternative narratives to the official government line could not get out to the public, except for very limited distribution political party newspapers like The Rocket and Harakah.

The kedai kopi was once the centre of political dissemination with printed media

Back in the early 1990s, former prime minister Mahathir Mohamed promoted Malaysia as an IT hub, promising there would be no censorship of the internet to attract foreign investors. After Mahathir surprisingly sacked his deputy Anwar Ibrahim in 1998, the online media quickly came alive with opposition utilizing the internet to carry their message.

Internet sites like Reformasi and Free Anwar blossomed, along with a number of blogs carrying the opposition message. Pages from these blogs were often printed out on mass and distributed around mosques and coffee shops for those with no internet to read.

Its not an understatement that Malaysian politics boosted internet usage across the country in urban areas, as nearly half the population wanted to read the alternative narratives to the government line.

Malaysia has always had a high number of political blogs, in the hundreds by the mid-2000s. M. G. G. Pillai was one of the early pioneers setting up the political blog culture. This era also witnessed the birth of Malaysiakini, pioneering a paywall news portal, which today has over 15 million visitors per month. This opened up a new era in news, political reporting, analysis, and comment. Malaysiakini and latter other news portals promoted letters to the editor, which has now become a major political forum.

The next era that propelled the influence of online news portals and blogs was the popularization of both social media and communication apps like Whatsapp, Line, and Telegram, etc. Malaysians have become heavy consumers of Op Eds in the form of letters to the editor from news portals and blogs. An Op Ed that gets a couple of thousand reads online may get tens of thousands of reads through the apps.

Online media did play a major role in assisting Pakatan Harapan win government back in 2018. How much cant be quantified, but without online media, there would probably not had been a change in government.

We are now seeing the pre-GE15 proliferation of new portals appearing online. Some of these sites claim to be news portals, others blogs, and yet others which push particular lines.

The rest of this article will provide a simple map of the online media, and show the relative influence of major sites, based on traffic. This will help us understand the phenomenon better and the role it will play in the coming election.

The cyberscape of news portals

There is a lot of diversity within online news portals in Malaysia. The 2018 Reuters Institute Oxford University Digital News Report indicates Malaysians are one of the heaviest users of Online news portals as a source of news and information.

Conventional Media: Many of the largest traffic sites originated as offshoots from the mass media. Sites like The Star and New Straits Times (NST) are expansion from newspapers. A relatively recent addition would be Astro Awani portal, an offshoot from the Astro TV. They carry a similar format to newspapers with news, analysis, and comment.

Much of the conventional media is owned by government, related political parties, or politically aligned companies.

Alternative Media: There is a wide diversity within the alternative media online portals. Some sites like Malaysiakini and Free Malaysia Today (FMT) carry news, analysis and comment. They have columnists who are usually relatively well-known commentators, and carry readers letters. They also have a staff of accredited reporters and journalists.

There is also a proliferation of portals which try to emulate the larger news portals. They may or may not have reporters, and fill a space under the major alternative media sites. What potentially differentiates these sites, at least among readers, are the commentaries they carry. Some specialize in geographic areas like Sabah and Sarawak. Others carry a particular editorial line.

Blogs: The Malaysian blogsphere is diverse. There are generally two types of blogs. Those that carry almost purely their own Op Eds, and those which reproduce articles published online on other sites. Some mix the two, carrying others articles with their own comments.

Social media: Online apps like Line, Whatsapp, and Telegram have propelled the distribution of online Op Eds many-fold. An Op Ed on a blog getting around a thousand reads can obtain 10-fold more through online group postings. This has dramatically extended the reach of the alternative media and blogs over the last few years.

Thus, social media enhances the influence of many low traffic blogs and Op Eds. Op Eds according to the readers analysis also get the higher reads on the alternative media sites than straight news articles. Influential columnists are one of the key differentials among the various sites.

Governance and Restriction

Malaysia placed 113/180 in the Reporters Without Borders 2022 Press Freedom Index. Online news portals or blogs don’t need a specific license to operate. However, reporters require a media accreditation card issued by the Department of Information. Online news portals should be registered companies with an official registered address, in order to receive media invitations from government.

Journalists and news portals are subject to a number of laws that restrict free speech. These include the Sedition Act 1948, the Official Secrets Act 1972, and the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998. In addition, at the beginning of the Covid pandemic the Emergency (Essential Powers) (No.2) Ordinance 2021 was introduced criminalising the circulation of ‘fake news’, which the government was the sole arbitrator in defining what is ‘fake news.”

There is no Freedom of Information Act, no whistle blower protection, and no legislation protecting journalists from disclosing their sources.

Malaysia’s online news portals practice strong self-censorship, especially upon the sensitive issues of race and religion. Ministers and ministerial staff if not happy with an article, they will request it pulled down, which many portals will comply with.

The government will harass online news portals they dislike. Back in 2015, after The Malaysian Insider published reports about the 1MDB financial scandal, the site was blocked from Malaysian IP addresses, so no one in Malaysia could access it, as a tactic to drive away advertisers. In February 2021, Malaysiakini was fined RM500,000 for contempt of court, where a third party had posted comments in the comments section.

Loss of trust in the mainstream media

People lost great trust in mainstream TV and print during the 1MDB scandal and turned strongly towards the alternative online media. Media Prima which owned Malaysia’s television stations, the New Straits Times, and Malay Berita Harian was making massive losses from low viewer and readership.

In addition, the ability to access online news portals on mobile phones also increased the popularity of online media. Social media has become a major source of news for many Malaysians today.

After the Pakatan Harapan won the 2018 election, government controlled and affiliated media changed their editorial policies becoming more balanced in reporting.

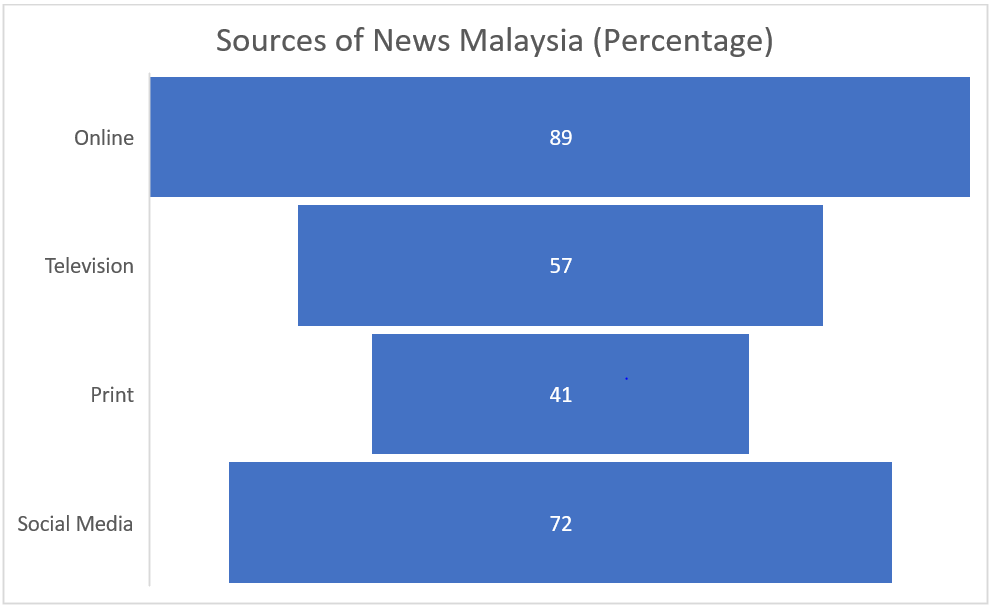

Source: Digital News Report Malaysia

Figure 1: The sources of news for Malaysians in 2019

This is where social media can amplify the messages of influencers. For example, the three month rounded monthly average on Dennis Ignatius website was 57,000 visits. His YouTube presentations can obtain more than 231,000 watches. Likewise, Mariam Mokhtar’s Rebuilding Malaysia blog averages around 6,500 visits per month, while her videos on YouTube are watched by 50-100,000 people.

Online portal market share and reach

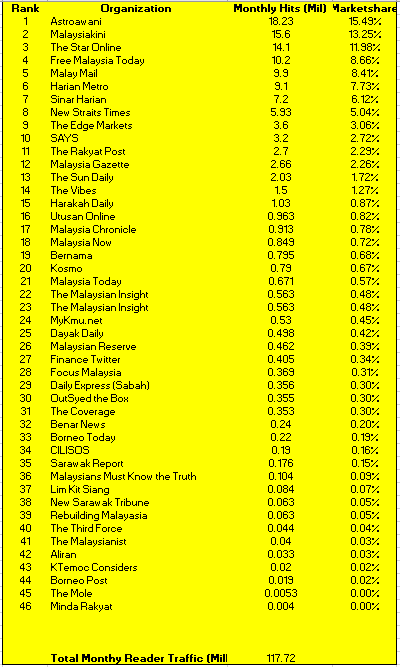

Below is a table based upon data from Similarweb. The last three months traffic to news portals and blogs is averaged and then sorted according to their market share in Malaysia. Some sites like Between the Lines are not recorded as their traffic is made up from sending out mailers to subscribers’ inboxes. Mailer services based on platforms like Substack are becoming more important as a means to circumvent censorship. International sites like Asia Times, Asia Sentinel, and Eurasia Review are excluded because they don’t exclusively report on Malaysia. An effort has been made to include as many blogs as possible with traffic over 10K hits per month (apologies for those missed).

Table 1: Malaysian online media traffic and market share

*Foreign based websites

The top eight online sites receive 76.68% of the traffic indicating a very concentrated market. However, the next seven online sites receive between one to three million visitors, on average per month. The next nine online sites receive between 500-999K reads per month. The next nine sites receive between 250-499K reads per month, making them sizable online portals. The rest of the sites have niche geographical, Op Ed, or special interest audiences, giving them influence over their readerships, where their content is disseminated over social media app mediums.

Below are some short profiles on some of the other influential online sites.

The rest of the online sites project beyond their direct readership figures due to a number of reasons. KTemoc Konsiders, The Vibes, The Coverage, The Scribe A Kadir Jasin, and The Mole have popular influencers with their individual followers. Syed Akbar Ali with OutSyed the Box is well known for his general commentary, as is Raja Petra Kamarudin with Malaysia Today, is one of the early online bloggers from the Reformasi days. The Malaysia Chronicle picks up others stories and Op Eds, highlighting important aspects. Finance Twitter has a very good reputation for its hard-hitting Op Ed pieces.

Bernama is a government news portal where other media organizations pick up their stories. The Malaysian Insight is a reconstitution of the now defunct The Malaysian Insider, experimenting with the paywall, emulating Malaysiakini. Clare Rewcastle-Brown’s Sarawak Report made its reputation as an investigative journalistic site, being one of the primary news portals that exposed the 1MDB scandal. The Malay Utusan Malaysia is a reconstitution of the defunct version, very quickly building a reputation for itself as an investigative journalism news portal.

Online sites like Borneo Today, The Daily Express, DayakDaily, New Sarawak Tribune, and Borneo Post cater for very specific audiences in Sabah and Sarawak. Harakah is the official PAS organ, famous for its days as a newspaper during the Reformasi times. Aliran is the official website of the organization.

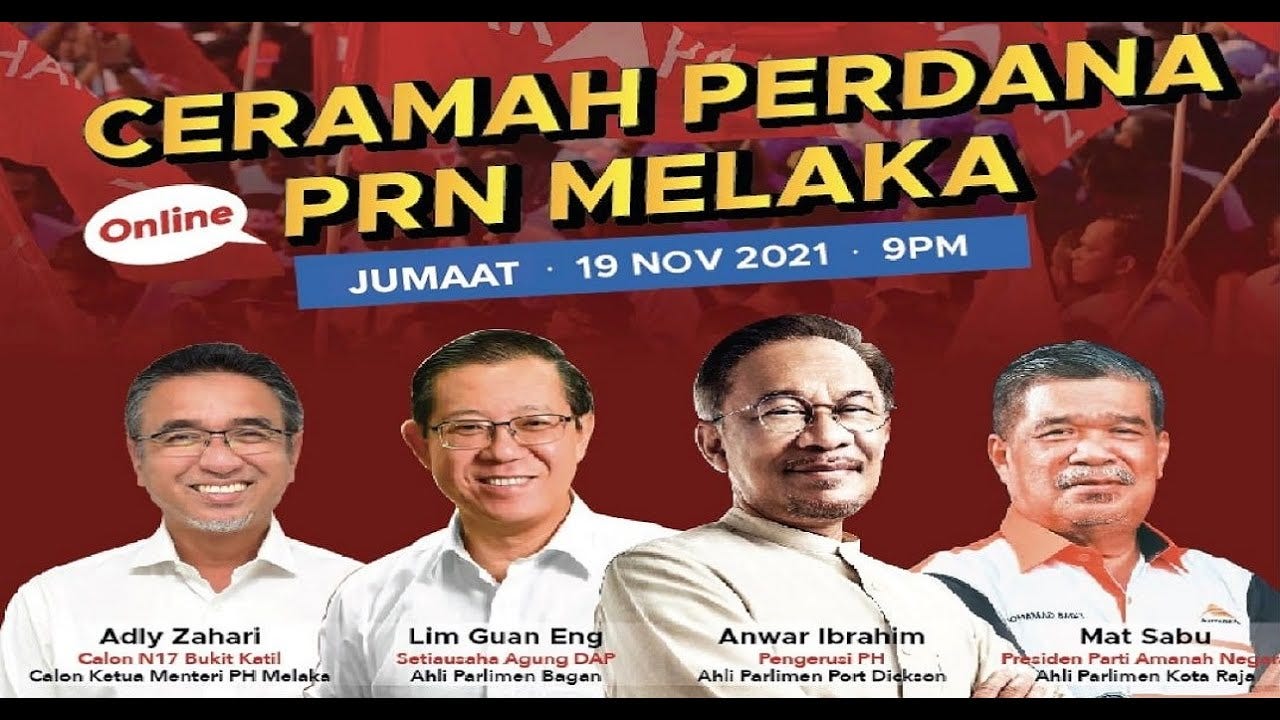

Online ceramahs may continue after Covid.

Conclusion – The major battleground

With GE15 not far away, online media is the major political battleground. There appears to be no relative advantage for any side of the political spectrum within its current stratification. What counts is that political parties thoroughly understand the structure and dynamics of Online media, and can use it for their advantage in getting the message out in a way it influences public opinion.

This means disseminating information to portals that will deliver the message to where it needs to go. Political parties will have to allocate substantial human resources to the task to deal with the various levels of portals and with selected influencers. The key is not generating readers onsite, but getting readers to share vital information through their chat groups for maximum effect.

As was seen in Melaka and Johor state elections, holding physical ceramahs or political meetings, aren’t the most effective means to get the message to voters. Political parties must craft the message online. This needs to be a major part of political parties’ primary election strategies. Lose the online battle and you have lost the election.

Subscribe Below: