Understanding the causes and the impact of emotions is important to the study of opportunity and strategy development. It is important to recognize our emotions and the role they play in influencing decision making. Emotional states can influence a person’s thinking and make behaviour irrational (Nesse 1998). The increase of the cognitive influence in psychology has brought emotional processes into focus (Greenberg and Safran 1989), especially within the context of entrepreneurship. These next two sections look at emotions and the ways they influence us.

Our basic emotions are primal urges that we share with many other members of the animal kingdom, except that the majority of animals do not have any cognitive capacity to turn them into higher order feelings, thoughts and concepts[1]. Emotions are part of our basic schemata and semantics at the imaginative and conceptual levels (Buck 1985) and their intensity assists us with memory retrieval. Higher order emotions tend to be socially constructed and occur within social interaction and relationships. Emotions can evolve, transform, change and take new directions in different situational contexts. Emotions can be positive or negative, expressed or not expressed and vary in intensity. Emotions play a role in our perception, thinking, decision making and communication with others.

Emotions, although not directly part of our cognitive systems, are very closely intertwined and have great influence over perception and decision making. Emotions add subjectivity to our experiences and trigger accompanying physiological responses which in many cases have motivational influences and behavioural consequences. Emotions are biological, social, cultural and personal.

If we subscribe to the notion that the process of opportunity identification and subsequent exploitation is not an entirely rational process, then exploring these activities through emotions may create some valuable texture and understanding to the subject that we miss through examining the process through the ‘more rational’ management process theories. Using metaphors such as nurturing and bringing up a child conjure up analogies that portray events as emotional, that traditional management process theories do not take into consideration and thus lack full meaning. The nurturing metaphor would bring understanding to the persistence someone would put into a business when results are poor (i.e., where a parent would not give up), exercise long term commitment with self sacrifice (i.e., the nature of life with dependent children), being an over-controlling founder of an enterprise (i.e., parents attachment to children), reduce the perception of risks (i.e., love may be blind), and treat the business like it is an offspring through commitment (i.e., a passion for work), etc (Cardon et. al. 2005). This enables us to ‘feel’ rather than think about opportunity exploitation in an emotional context with an intensity that exists within these processes that we cannot understand through using management process theories.

To understand who a person is, it is necessary to understand emotion. Emotions help us to learn and are an integral part of how we make sense of our lives. We find ourselves feeling strongly about something without really knowing how these feelings come. Our basic emotions come from inner extra-rational dynamics within our psych (Chodorow 1999) that are expressed as feelings, dreams, fantasies and other imagined aspects of our lives. Emotions are part of our fundamental irrational and unpredictable side to our self. Emotions show our basic urges, desires, repulsions and dislikes about what we see, feel and perceive in the environment. This subverts our sense of rationality, sometimes giving us multiple and contradictory feelings at the same time. For example getting angry at someone and then felling guilty about it. Yet behind these conflicting emotions maybe deeper emotions exist, as the feeling of been left out or not being part of the group – even a low feeling of self esteem. In a Jungian way, emotions are a window into our deep inner selves that are exposed through our daily experiences in the world.

Emotions provide personal meanings for everyday occurrences (Chodorow 1999). Emotions animate our thoughts into actions and behaviour which connects us to an event and social interaction. Thus emotions connect our inner selves with the outside environment and also with our interrelationships with others. We reflect using our emotions and touch our spiritual and moral inner world through what we feel through our emotions (Dirkx 1997). Emotions can amplify or circumvent the power of our ego and desires, thus encouraging or restraining any actions we take through specific feelings (often manifested with multiple feelings) that are generated within us. These urges are usually able to be controlled through the discipline of our reasoning, but in extreme situations become uncontrollable (Jaggar 1989), showing the inner conflict between our rational and irrational selves.

Emotions usually exist in multiplicity and as such often conflict with each other. In an ongoing enterprise where decisions have to be made, a person may be “pulled in two conflicting directions” by the emotions he or she has. Take for example in a family company where a long time employee must be disciplined or terminated for some grave misconduct. There may be mixed feelings that create tension and reluctance to take action when at the same time there are feelings that action must be taken in the interests of the enterprise (Fuller-Love and Thomas 2004).

Each event, object or person we perceive will bring about some form of response. This will occur in the form of emotion which is a form of psychic energy and generally provides driving or restraining forces behind a person’s intent. Emotions may be short lived or persist for long periods of time. They may be dependent on internal processes or a reaction to the outside environment. Emotions can vary in intensity and be shaped by our cultural and social situations. While undertaking any tasks, emotions will tend to fluctuate widely and affect our level of creativity, energy, passion and persistence.

Emotions relate to our general temperament and functioning in life. They provide feeling states which influence what we want, what we do and don’t do, and who we meet and interrelate with. Emotions influence our general beliefs and attitudes, providing feelings upon which courses of action we intend to take, places we want to go and people we want to associate with (Ashkanasy and Daus 2002). They create states of caution, persistence, patience, excitement, restraint, boredom, encouragement, confusion, hesitancy, challenge, mastery and enthusiasm within us. Therefore it stands that with changing emotions we also change our physiological state and behaviour.

Our higher emotions are a message to others and are interpreted according to our culture and social situations. Emotions are part of communication and colour our perceptions of organizations and relationships with others. People observe our emotions and read meaning based on the types of emotions we display or fail to display within any situational context (Brundin et. al. 2008). Examples of everyday use of emotion in our society include the supermarket cashier’s smile and an undertaker’s expression of sadness when in the presence of the widow (Rafaeli 1989). People expect to experience certain types of emotions in certain social and cultural situations to create an atmosphere of safety and stability. Perceiving a different set of emotions would create tenseness, frustration, anxiety, discomfort and even fear in a social situation.

Positive emotions in a social context lead to higher involvement in tasks (Lyubomirsky et. al. 2005), tolerate higher levels of stress (Baron 2008), and lead to more efficient decision making (Isen 2000). A negative emotional environment may result in avoidance behaviour (Krause 2004) and the hesitancy to take risks (Higgins 2005). Positive emotions can also have negatives consequences as well as negative emotions having positive consequences as Table1. indicates.

Table 1. The Positive/Negative Consequences of Positive/Negative Emotions.

Organizations have been designed to eliminate emotion that would interfere in rational decision making (Weber 1978, 1981, Simon 1997). So much effort has been made in business schools and throughout the rest of our education systems to promote rationality as the basis on action. Although rationality is given this supreme position, the reality is that many issues are decided upon by emotional rather than rational thinking. Emotion is sublimed through the education process, although taking a central part in our cognitive and learning processes.

In the entrepreneurial context many decisions are made under ambiguity and uncertainty. There is a high probability that the entrepreneur will have very intense emotions when making decisions (Baron 2008). Decisions are made in the absence of precedent and information, thus relying upon one’s reasoning, intuition, feeling and reckoning.

Opportunity is a prediction of a potential future outcome, but any accurate prediction of the future is impossible. Emotions influence the process of decision making, as it is impossible to make any rational type of decision regarding the future (Elster 1999). It can only be an objective, goal, aspiration or hope. People will make decisions based on intuition and wisdom, which rely on stored knowledge in the long term memory and its retrieval, rather than the present situation in the environment. Before making any decision, a person will tend to weigh up the issues on the matter and take some form of ‘calculated risk’ in the decision they reach. This is the work of using tacit knowledge or heuristics and emotion. Emotion prioritizes what heuristics to use by recalling the pleasantness, unpleasantness and intensity of the associated emotions. Stimulated by events, our emotions attract our attention to heuristics that are associated with the more intense emotions[1]. Our cognitive processes will retrieve mental models associated with intense happiness, sadness, anger, frustration, grief, worry, complexity, etc (Simon 1997a).

The range of emotions we have are wide and it is not generally agreed how many emotions actually exist and what they actually are (Frijda 1986). The basic emotions may have been biologically derived from our earlier primal existence which aided our survival within a dangerous environment (Greenberg and Safran 1989). Some of our most basic emotions include anger, fear, sorrow, joy, envy and greed. These appear to be wired into the human organism (Arnold 1960, Leventhal 1984) and specific codes of behaviours correspond to specific primary emotions (Ekman 1972, Ekman and Friesen 1975).

The basic emotions (particularly the unpleasant ones) also generate physiological responses such as needed in the fight/flight mode when we came in proximity of a threatening animal. The brain would release adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream to enable faster thinking and actions. The brain would drastically increase its activity. The body would freeze with all senses focused on the perceived threat. The heart would beat faster, ready for a quick getaway. Blood is diverted from the skin to the limbs to enable quick and powerful movement. Blood pressure rises and respiration increases. The muscles are tensed and sweating increases to cool the body. Appetite is suppressed and the bowels relaxed so that a person will be lighter for a getaway. These emotions are involuntary and often experienced without recourse to our consciousness or intervening thought processes[2].

The key to our emotion generation is the appraisal process within our cognitive system. As the situation gets reinterpreted and reinterpreted, secondary emotions begin to be generated at a more conscious level. Emotions occur when a person is aroused after detection of some form of stimuli. This immediately changes the base level of arousal where perhaps a genetically encoded response is triggered, such as a response to the danger of a snake or spider, etc. This response immediately prepares our senses and body according to the significance of the threat. There will be a physiological response and behavioural intention after identification and a clear understanding of the situation is gained.

From the evolutionary viewpoint, the properties of stimuli that create pleasant emotions aim towards sustaining life and the properties of stimuli that take aversion to things that are incompatible with life (Panksepp 1988). Though essentially our basic emotions were biological responses to danger, threat or loss, as well as an aid to seek out ways to nurture human needs, in the modern world, threats and dangers don’t exist as they did in the primal world. These physiological states are only intended to last a few moments while one deals with a perceived threat. With the stress of today’s society and the prolonged emotional state many people experience, some of the above described physiological actions like high blood pressure become pathologies in individuals trying to cope with long terms stress.

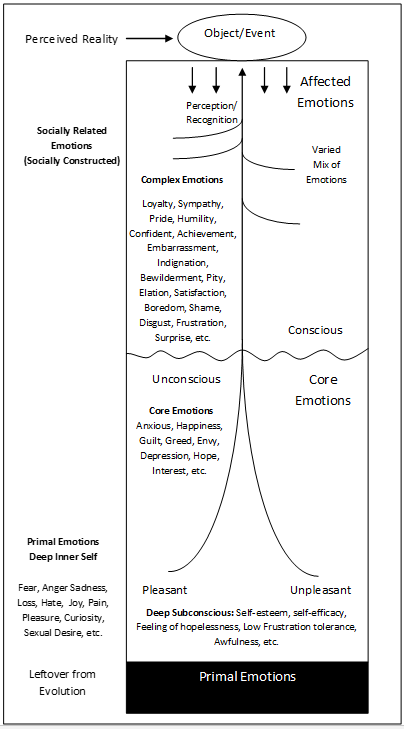

There is a range of emotions that are much more complex than the basic emotions. The higher ordered emotions are more socially related and usually show to others our feelings and the meaning we make of the situation. They are our response to meaning (Lazarus 1999). Socially constructed meaning is a large part of what emotional experiences are about. We answer a situation from mental models built upon our experiences stored in our long term memory. Upon subsequent appraisal, our cognitive processes determine the intensity we respond to the situation with our emotions (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Learned ‘core related themes’ are believed to influence this automatic appraisal process (Smith and Lazarus 1993). Therefore higher order emotions are social constructs. To be angry, disgusted, humiliated and proud are moral positions (Harre 1991). These social emotional positions are coded into memory schemata and they become automatic responses (Leventhal 1982). These socially related emotions will also have some relationship to the basic core emotions (Greenberg and Safran 1989). The hierarchy of our emotions is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Hierarchy of Emotions

Socially related emotions have evolved through the influence of family, social and cultural influences. We learn the basic forms of these higher level emotions and tend to use them when culturally and socially appropriate (Stanley and Burrows 2001). All the higher level emotions can be represented as complex interactions of the basic emotions.

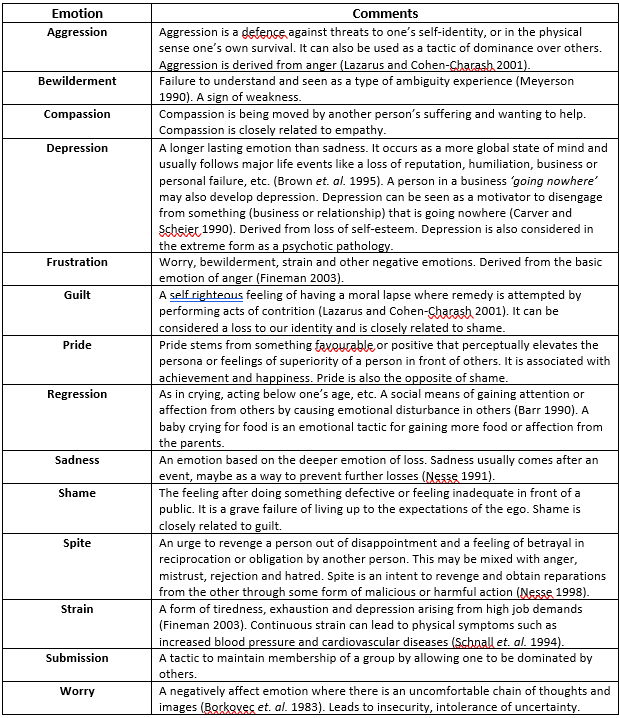

Emotions may not have direct opposites like happiness and unhappiness. Both these emotions can be experienced at the same time, as they are independent dimensions (Bradburn 1969). For example, lack of happiness does not necessarily mean unhappiness and vice versa. Some of the more common socially derived emotions are listed in Table 2. Below.

Table 2. Some Common Socially Derived Emotions.

Our core emotions help maintain a unitary feeling within us along a particular mood theme. However the more socially related emotions provide us with mixed and complex feelings, which are often conflicting and flowing backwards and forwards in their individual intensities, leaving us in indecisive decision making capacity or in the more extreme situation, confused disposition. We experience a whole range of different emotions at the same time which partly overlap and partly conflict with each other. This would be something like the wait at an amusement park for some sort of exhilarating ride where expectation, excitement would be accompanied by some fear and hesitancy. Whether one decides to get on the ride or not will depend upon the balance of emotions at that very time, i.e., the excitement and exhilaration would be stronger than the fear and hesitancy. Decisions about opportunity and strategy may be just like the amusement ride but with less immediate intensity for many entrepreneurs.

Our whole emotional state is affected by a balance of affected and socially related emotions, core emotions and primal and deep sub-conscious emotions. What drives the higher emotions comes from both the environment and what is deep within our sub-conscious. Therefore in understanding our own emotional state it is important not just to look at the expressed higher emotions, but at the deeper emotions that may be driving them. Thus our experience of reality is a meta-experience made up of the set of all our emotions, the environment, and our self.

To some degree our decisions are influenced by the moods we are in. Therefore according to research, happy entrepreneurs with positive emotions tend to be more successful than sad entrepreneurs because happy people focus on learning new knowledge, new skills, and maximize their social contact with others. This increased involvement with their environment leads to more success (Baron 2008, Fredrickson 2001).

Most psychotic states are emotional states and driven by the person’s social conflict (Nesse 1998). When emotions become very intense and prolonged, they create a dysfunctional state, leading to deep fears and anxieties. This develops in the extreme into pathologies like paranoia, compulsion, schizophrenia, depression, dramatic behaviour tendencies and narcissism. Within any of these situations a person will always look for danger and threats and maintain an aroused nature of anxiety, fear or depression. This will greatly affect a person’s cognitive processes and rationality when holding underlying believes of fear, pessimism and danger, etc. Our emotions affect the relationships we have. Some people fly into rages at the slightest irritation, while their partners stay with them for years out of infatuation, security or the fear of leaving. Couples can spend a great amount of time and energy fighting but stay together. Some parents will feel the excitements of having children, while others will feel neglect from their partner and seek intimacy and affection from third parties. Some people will spend a whole career of helping others, but neglect their own family and children. Parents mourning a loss of a child may neglect their other children and sub-consciously blame the other partner for the loss. Our behaviour is rarely rational because of our emotions.

Emotions can enhance or impede our learning. Emotion is a very important part of our individual learning experiences and enables newly learnt knowledge to become psychically connected with our selves through the intensity of our emotions (Dirkx 2001). Emotionally charged images and other information are more vividly remembered and thought about than material that does not invoke any emotions. This is partly why shock enables a person to quickly make changes to their personal lives[1]. The emotions we experience with learning gives meaning to new information within our self and social setting.

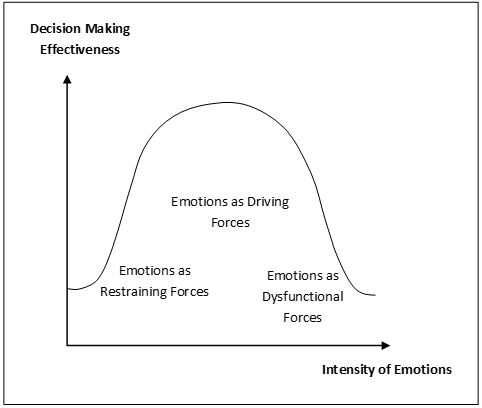

Emotions affect enterprise effectiveness through acting as restraints on action or driving forces towards action. Emotions can signal potential danger, thus cautioning a person to examine a situation more carefully before making a decision and acting. The sublimation of emotions also has the effect of restraining action. Honest acceptance of our own emotions act as one of the prime driving forces of a person behind our passion, persistence and determination. Finally we will see in some of the psychotic states examined ahead, that emotions can become delusions biasing perceptions, judgments and decisions a person makes thus reducing the effectiveness of perception and decision making. Figure 2. below shows graphically the influence of the intensity of emotions on effective decision making.

Figure 2. Intensity of Emotions and Effectiveness of Decision Making

Emotions affect a person’s propensity to pursue growth, recognize potential opportunities, achieve balance between work and leisure, and manage effectively. Their personal performance is affected by the nature of their experiences and corresponding emotions that are generated. This issue is not the event itself, but whether it was a pleasant or unpleasant experience. The list of potential emotions with each experience is wide. Everyday activities like dealing with customers, competitors and the market will generate ambiguity, anger, bewilderment, concern, confidence, fear, frustration, impatience, loneliness, resignation, satisfaction, strain and stress which will either endear or discourage a person from making like decisions and actions in the future. There will be periods of a sense of control and stability and other periods of stress and a feeling of being out of control. Metaphorically this may be like sailing a yacht within calm seas and a light wind and sailing in rough seas with strong winds where one struggles to keep the yacht from capsizing. As people have different dispositions, some will enjoy the calm and dread the wild, while others will be impatient during the calm periods awaiting the challenges of the rough seas. This takes a person away from rational thinking and actions. How emotions influence our perceptions, thinking and decision making is shown in Figure 3.

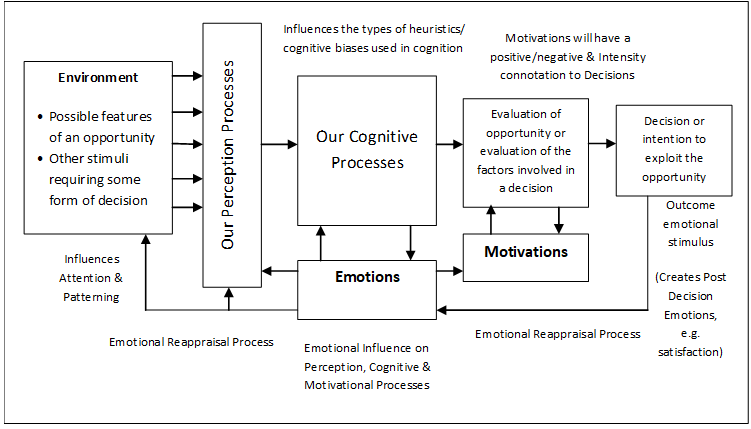

Figure 3. How emotions influence our perceptions, thinking and decision making

As Figure 3. shows our judgments and decisions are influenced by our emotions and thus our affected states at the time of making decisions are very important. Our emotions and their intensity affects us at the point of perception through attention and patterning, within our cognitive processing through the heuristics and cognitive biases we utilize and through to influencing our motivations to seek, see, construct and discover opportunity and make any decisions. Emotion also continues its influence on perception, cognitive thinking and motivation through the reappraisal process.

The people, objects and events we experience partly influence our emotional experiences based on any prior experiences with similar people, objects and events. Each experience has a positive or negative impact with a specific degree of intensity. This positive/negative valence with its level of intensity will have some effect on our cognition and behaviour. These factors will help in deciding the persistence, dedication, commitment, focus and energy we will allocate to our chosen behaviours. However each effect from emotions will be very specific to individuals depending upon the type and intensity of core emotions and the balance and mix of socially related emotions. The types of emotions each individual feels will also be driven by some deep subconscious and primal emotions that one has suppressed below their consciousness. A person must be aware of the influence and attachment one has to these deeper sub-conscious emotions as they are sublimely guiding thinking. We may not realize the influence of these deep sub-conscious emotions as they are manifested in our core and complex socially related emotions.

[1] For example when a doctor provides a patient with a diagnosis that is threatening, the patient will easily change their lifestyle to rid themselves of the sickness.

[2] Albert Ellis postulates that when we experience undesirable events about which we may have rational or irrational beliefs, we will become emotional over the event, leading to cognitive and behavioral consequences (Ellis and Dryden 1997). Irrational beliefs will be based on our deep subconscious self assumptions like the feeling of hopelessness, self-esteem and self-efficacy, etc (Ellis 1991). David et. al. (2002) classified these irrational beliefs in four categories; evaluation of self-worth, low frustration tolerance, awfulizing, and demandingness. Therefore rational beliefs will result in functional behavior and irrational beliefs will result in dysfunctional behavior.

[3] What is interesting is that Charles Darwin (1872) postulated that emotional expressions are not cultural and part of our global genetic makeup.

[4] Some theories of emotion see all emotions as socially constructive and not evolutionary.

An extract from Opportunity, Strategy and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 1, Nova, New York, 2012, pp. 245-255

Subscribe Below:

A very interesting/ insightful article. It brought me back to my sociology/ business psychology lecture hall that many years ago. If only my lecturer was half as interesting!