Reassessing the Chola naval expeditions to Southeast Asia: A maritime rivalry, not imperial expansion

P Ramasamy

The aim of the article is to show that the Chola expansion in Southeast Asia in the 11th century was not imperialistic in design but due to maritime rivalry with the SriVijayan kingdom.

The Chola naval expedition to Southeast Asia, particularly the capture of Kedah during the reign of Rajendra Chola, has long been a subject of historical intrigue.

While Anirudh Kansetti highlights the role of Tamil merchant guilds in facilitating Chola expansion and seeks to glorify this chapter of history, his analysis omits critical context regarding the motivations behind these expeditions.

A nuanced understanding suggests that the Cholas’ actions were driven by maritime rivalry rather than imperial ambitions.

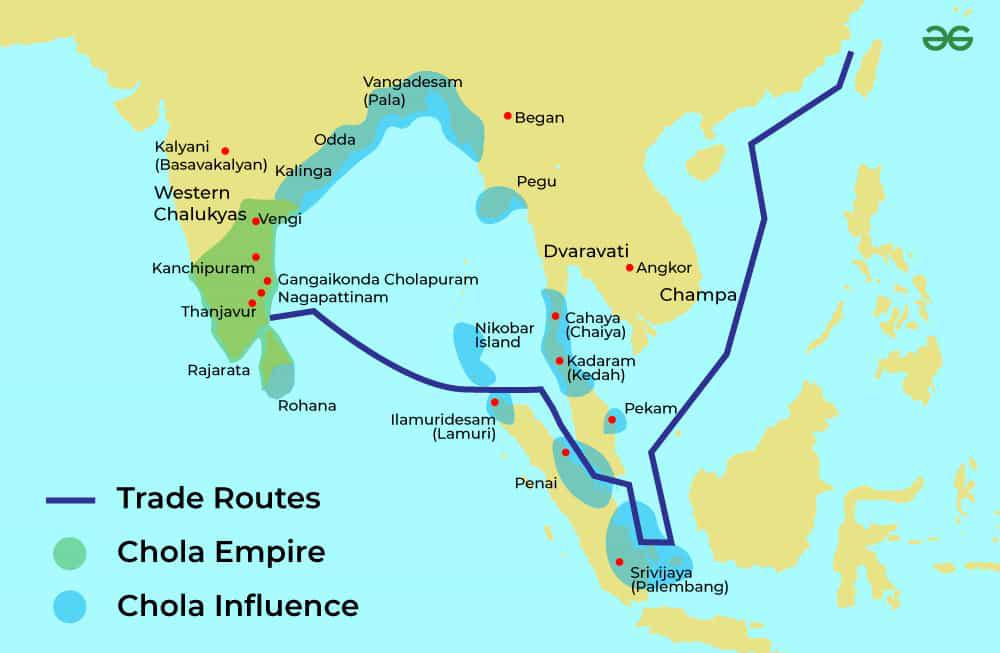

11th Century Chola Empire

A Tamil inscription dated to the 11th century, housed in a museum in Aceh, Indonesia, underscores the significant role of Tamil merchants in Southeast Asia.

This corroborates the notion that Tamil merchant networks were instrumental in expanding Chola influence across the region.

However, the Chola campaign against the Srivijayan Kingdom, including the sacking of Kedah and other settlements such as Beruas in present-day Perak, Malaysia, was less about territorial conquest and more about rectifying imbalances in maritime trade.

The Srivijayan Kingdom’s preferential treatment of China, granting it “most favored nation” status, strained its relationship with the Cholas, a rising sea power.

This friction culminated in Rajendra Chola’s naval expedition, aimed at dismantling Srivijayan dominance over key maritime trade routes.

The excessive taxation imposed by Srivijaya on Chola ships further fueled tensions. The Cholas sacked Kedah and other Srivijayan establishments along the west coast of the Malay Peninsula to assert their maritime authority.

Historical records suggest that the Cholas remained in Kedah for 66 years before withdrawing.

Interestingly, inscriptions on the walls of the Thanjavur temple indicate that Rajendra Chola restored Kedah to its former rulers before returning to India.

This act challenges the notion of the Cholas as imperialists with territorial ambitions. Instead, their actions align more closely with efforts to secure maritime dominance and trade interests.

During my tenure as a senior fellow at the Institute for Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) in Singapore, I organized a two-day conference in 2007 focusing on early Indian influence in Southeast Asia and the Chola naval voyages.

Scholars from around the world presented evidence supporting the view that the Chola expeditions were not driven by imperial aspirations but by a desire to challenge Srivijaya’s maritime policies and dominance.

Despite these findings, there remains a tendency among scholars to glorify the Chola naval campaigns.

This glorification often overlooks critical evidence, such as the sacking of Beruas alongside Kedah, and fails to consider the broader geopolitical dynamics of the time.

For instance, the historical and archaeological evidence in Kedah, particularly in the Bujang Valley, leans more heavily toward Srivijayan influence, with minimal traces of Chola presence.

The Tamil term “Kedaram” may link to Kedah, but the tangible evidence of Chola activity in the region remains elusive.

Interestingly, Chinese records may hold more substantial accounts of the Chola expeditions than Indian sources, such as the inscriptions at Thanjavur.

During my interactions with Indian historians and archaeologists at the 2007 conference, I inquired about evidence of Chola ships. Their response suggested that remnants, if any, might lie buried deep beneath the Bay of Bengal, awaiting discovery.

The Chola expeditions, while historically significant, must be understood within the framework of maritime rivalry rather than imperial conquest.

The capture of Kedah was not an attempt to subdue the Srivijayan Kingdom but rather a response to economic and strategic provocations.

As historians, we must move beyond glorification and focus on corroborating historical narratives with hard evidence.

P. Ramasamy

Former professor of political economy at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) and former deputy chief minister of Penang.

Subscribe Below: