Resetting Higher Education: Returning to the Community

The scholastic model that led to educational grotesquerie has failed. Time to move on

The state restrictions placed on public places in response to the Covid-19 pandemic has put great strain on higher education, effectively mothballing campuses without staff or students on site. Students have reacted tepidly to online teaching alternatives activated after the pandemic restrictions while staff are frustrated. Arguments about fee restructuring for virtual education formats remain largely unresolved.

With universities under this kind of great strain, an opportunity arises to reset higher education. While, there will always be an important role for well-endowed institutions of higher education, many of the weaker private and public institutions are likely to either fold, amalgamate, or restructure themselves in some major way, particularly where governments won’t be bailing them out.

The higher education environment is now radically changed, with many low-income students unable to afford tuition fees, sources of income from foreign students are blocked in at least the short term, institutional fixed costs are extremely high, and with high graduate unemployment, the value of earning a degree is being increasingly questioned.

Consequently, higher education needs a renaissance. It needs to be relevant to earning incomes, affordable, without evolving into a debt trap, accessible without the need for students to be isolated on campuses, and provided to the community at a low institutional cost. It needs to go back to the grassroots, emulating what the technical and community colleges once were.

The mega-concept didn’t absorb faculty costs. Repressive quality schemes weren’t worth the cost and effort, as educational standards have actually decreased. University tenure systems are expensive, producing a cohort of narrow experts, rather than a community of generalists who can instruct holistically within disciplines and teach students how to solve practical problems.

This is the case of management, and many of the technical disciplines within the spheres of science, engineering, and agriculture, can revert to employing ‘pracademics,’ people who have industrial as well as academic experience. That opens up the nexus between academic and vocational education, something that would enhance job appeal. In areas where few job vacancies are available, entrepreneurship and the creation of new enterprises, coupled with a technical and practical grounding in the skills needed in selected activities, would create much value-added assistance to revitalizing communities.

There can be small specialized university-colleges for the professional disciplines of law, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and the like to produce those destined for a professional life. The humanities, such as history, languages, art, etc., could follow the small institute model as well, for those who want to pursue education as an intellectual, rather than vocational goal.

This model can assist in development. In Thailand, the faculty of Agriculture of Prince of Songkhla University set up a successful pilot program called the MBA, or Moving by Action. Farmers and families were invited to campus for a semester-long course, in the mornings learning small business, marketing, and entrepreneurship, and in the afternoons learning farming, food production, and packaging. Many graduates of this initiative have gone on to create and sustain SMEs.

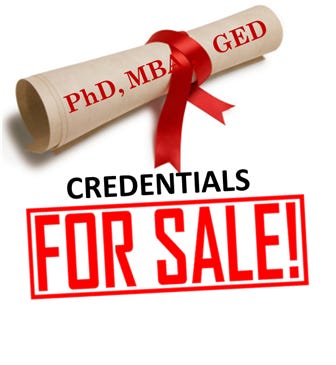

What is unsustainable needs transformation. We have reached the ludicrous situation where a store assistant requires a degree to get a job serving in a retail-based business. Shop assistants need degrees, as do bank tellers, office clerks, and even cashiers in department stores. Universities have done the community a great disservice in talking up the value of a degree, which has led to inflated expectations of graduates and employers.

The biggest challenge is going to be helping people get employment after the Covid-19 pandemic is over. Unemployment is rising rapidly, predicted by some to reach levels that existed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Higher education has to transform to do its part in solving this problem, and at the same time save itself from extinction. The key objective of higher education is to once again teach people how to learn.

Higher education institutions need to be freed from their self-imposed regulatory shackles and management cultures. It is no longer about being a global educator, but going back to becoming a community educator. This will be the greatest challenge facing higher education during the coming decade.

Taking a look back, the university institutional model grew out of traditional community-based technical colleges in an era where investment in social educational wellbeing and technical expertise were valued over profit. The 1970s saw exponential growth in higher education, which was regarded as a right for all in welfare societies. The 1980s and 1990s saw the development of large conglomerate universities, with smaller institutions merging, multi-campus models developing, and university status was coveted.

These institutions, led by a new breed of academic-administrators, developed their institutions until they became mega-universities. They had to make a go of it primarily as financially independent organizations, jumping into all teaching opportunities, franchise courses, and contract-based research, and developing novel ways of attracting benefactors.

Very few within or outside the higher education industry saw what was to come. Putting the damage from Covid-19 restrictions aside, higher educational institutions were already facing major challenges due to a demographic-cliff that cut across much of the developed world and Asia, leading to shrinking domestic student numbers. These gaps were met by foreign students, which edged university missions away from serving the educational needs of their respective communities toward a business orientation towards the international student market.

The financial well-being of many private universities, as previously reported by Asia Sentinel, were already under financial strain long before the onset of Covid-19 closed them down, indicating that at some stage there would be a rationalization. Adding to the problems were rising numbers of unemployed graduates and postgraduates, a decline in demand for postgraduate courses, and unemployed PhD holders. Universities are in many disciplines producing graduates in surplus to the jobs available.

The rise of the mega-university didn’t bring educational excellence. Actual courses have been aimed at the lowest denominator. The textbook culture has overtaken teaching, with students able to run to online essay mills for quick-fix assignment fulfillment. Teaching compliance systems like Objective Based Education (OBE), and faculty-based ISO accreditations have turned teachers into administrators, erasing teacher preparation, research, and teaching time. Lowest-common-denominator teaching was encouraged by growing numbers of foreign students who don’t have sufficient grasp of the language of the medium of instruction. Standards have been declining, with students taught to imitate, rather than extrapolate the knowledge they have into solving problems.

Very little university research is actually commercialized outside of top universities like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Caltech, and Stanford, which have become centers of communities like Silicon Valley. New innovative intellectual property generated has little social or enterprise value.

Many pieces of university research end up being solutions that seek a problem. Modeling presented to the world on future catastrophes has time and again been found wanting. This was seen in the 2008 financial crisis, when Professor Tim Besley of the London School of Economics, acknowledged that the economic fraternity ‘lacked any collective imagination’ to see what was coming. On the whole, professors have been poor communicators of their disciplines.

The reality is that teaching academics take classes today, just as high school teachers do. Administrative professors run faculties as a business manager would. The majority of research papers produced differ only in micro-context, adding little if anything to the collective knowledge. In fact, academia has created a pay-to-publish scam as many academics rush to produce papers to meet key performance indicators to further their careers. Very little of this research finds its way into course curricula.

Published in the Asia Sentinel 24th June 2020