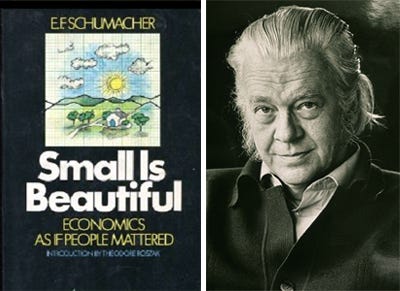

E.F. Schumacher’s classic book Small is beautiful was a product of the times he lived in. The Club of Rome had been warning of the consequences of pursuing economic growth without limits. The measure of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was being questioned for not counting externalities like the consumption of natural resources, and not factoring in wellbeing by some liberal economists. Likewise, there was growing criticism of the roles of trans-national corporations and questioning of the basic wisdom of foreign aid.

Schumacher questioned the wisdom of big government at a time the European Community was nurturing a mega-government that imposed regulation upon the smallest village. Schumacher was one of the early questioners of growing regulation, which was being accompanied by massive increases in bureaucracy to enforce the regulations bureaucrats thought up. Schumacher also incorporated the workplace and organizational values developed at the Tavistock Institute; at a time, they were considered radical.

Schumacher was ground-breaking in his concepts of scarcity, finite resources, and the need for environmental sustainability, a forerunner of the modern environmental movement today.

Most importantly, Schumacher challenged the basic notion of economic growth, pursued under the illusion that the Earth has infinite resources. He challenged the very core of the economic problem postulated within the logics of Keynesian economics.

Schumacher critiqued current habits of consumerism, which are based on wants rather than needs, postulating that the invisible hand is too important for society’s choices to be left to fate.

Weaknesses in development economics

Schumacher was damming about economic development in the third world, and the West’s role in it. Standard development strategies have primarily emulated the Western industrial practices to create employment.

However, this led to the creation of mega-cities and a massive drain upon rural communities, as people flocked to cities for employment. This decimated rural communities and public infrastructure development became skewed towards cities. Crowded mega-cities created slums, industry created unabated pollution, while quality of life declined.

Foreign investment increased development, but at the cost of high environmental degradation. The technology multi-nationals transferred didn’t enhance workforce skills. Respective education systems focused on producing industrial fodder, rather than focus on creating a pool of skilled craftsmen, and an educated professional class. Education distinctly lacked any substance to develop critical thinking, creativity, and innovation. The local education system did little to nurture indigenous enterprises.

Foreign aid wasn’t crafted to develop the economies of recipient countries, tending to enhance the agendas of donors. This hasn’t been in the interests of recipient countries.

Rising prosperity and advertising encouraged mass-consumerism based on wants rather than needs. This time and time again created markets for imported luxuries, rather than local products.

Foreign investment brought inappropriate solutions for developing countries, where new solutions specific to the situational nature of the country was needed.

Even though the above observations about development economics were made back in 1974, almost 50 years ago, there are distinct analogies to development today. Many rural and even urban areas around the world today, including many within post-industrial societies urgently require revitalization. This is particularly the case after 40 years of globalization where low labour cost countries became the factories of the developed world.

The Schumacher hypothesis

Schumacher saw that under the current economic system, the poor would get poorer and the rich would get richer, increasing the wealth divide.

Consequently, Schumacher published his alternative manifesto, calling for a new direction in development.

One of the biggest problems are mega-metropolises which soaked up national resources, became home to isolated conclaves, were unsustainable and generated the majority of a nation’s pollution. Schumacher believed cities over 500,000 people were undesirable and there should be progressive decentralization.

Focus could then be put back into revitalizing communities built upon sustainable numbers, according to the quality and sparsity of available hinterlands. These communities would engage in creating enterprises and food production that would sustainably serve their immediate communities. These enterprises could vary in the way they were owned, organized, and operated, based on empowering people and maximising members’ wellbeing. Appropriate technology that could be constructed locally, that was affordable, and connected people with their work and enterprises is the much more important than the established concept of economies of scale. Appropriate technology would create value and bring economic wellbeing to local communities.

Some legacies

Schumacher’s work brought a refocus back to sustainable and organic farming after the world became dominated by fertilizer production from the green revolution. This allowed for the formation of many boutique farming enterprises around the world, where there are now a host of organic food products on the market.

Companies like the Bodyshop and Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream were formed and developed using Schumacher’s community principles, but were eventually bought-out by multinational corporations. Japan’s One Village One Product (OVOP) and later Thailand’s One Tambun One Product (OTOP) programs were based upon Schumacher’s principles and successful in their time.

Schumacher’s educational principles were taken up by academics like Peter Senge in the 1990s with his seminal book The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. The ideas were incorporated directly into education in the 2000s with Schools that Learn: A Fifth Discipline Fieldbook for Educators, Parents and Everyone Who Care about Education.

Schumacher highlighted the illusion of economics as resources were infinite, leading to a movement towards utilizing renewable inputs in products. Schumacher also alluded to the tendency of humans to accumulate a perception of unlimited powers, and an assumption that humankind’s mastery over science, gave control over the environment.

Schumpeter and “The Great Reset”

Schumacher questions Keynesian economics, socialism, and conventional forms of ownership in society. He also questions the public benefit of trans-national corporations, and the dehumanizing aspects of displacement technologies. Large centralized governments don’t make the best decisions for communities, and we are now in a vacuum of virtue, wisdom, and morality within leadership and bureaucracy.

The World Economic Forum’s Great Reset is the anti-thesis of Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful concepts. Many critics of The Great reset claim it is being imposed upon societies by stealth, rather than after open discussion and debate.

The centralization of government, participation in government of corporations, science based upon forecasts rather than evidence-based research, the introduction of capital-intensive Industry 4.0 technologies that the poor cannot afford, and the rise of top down authoritarianism, are all against what Small is Beautiful argued for.

This is the brave new world Schumacher warned the world of.

Subscribe Below:

A very timely revisit! Many thanks.