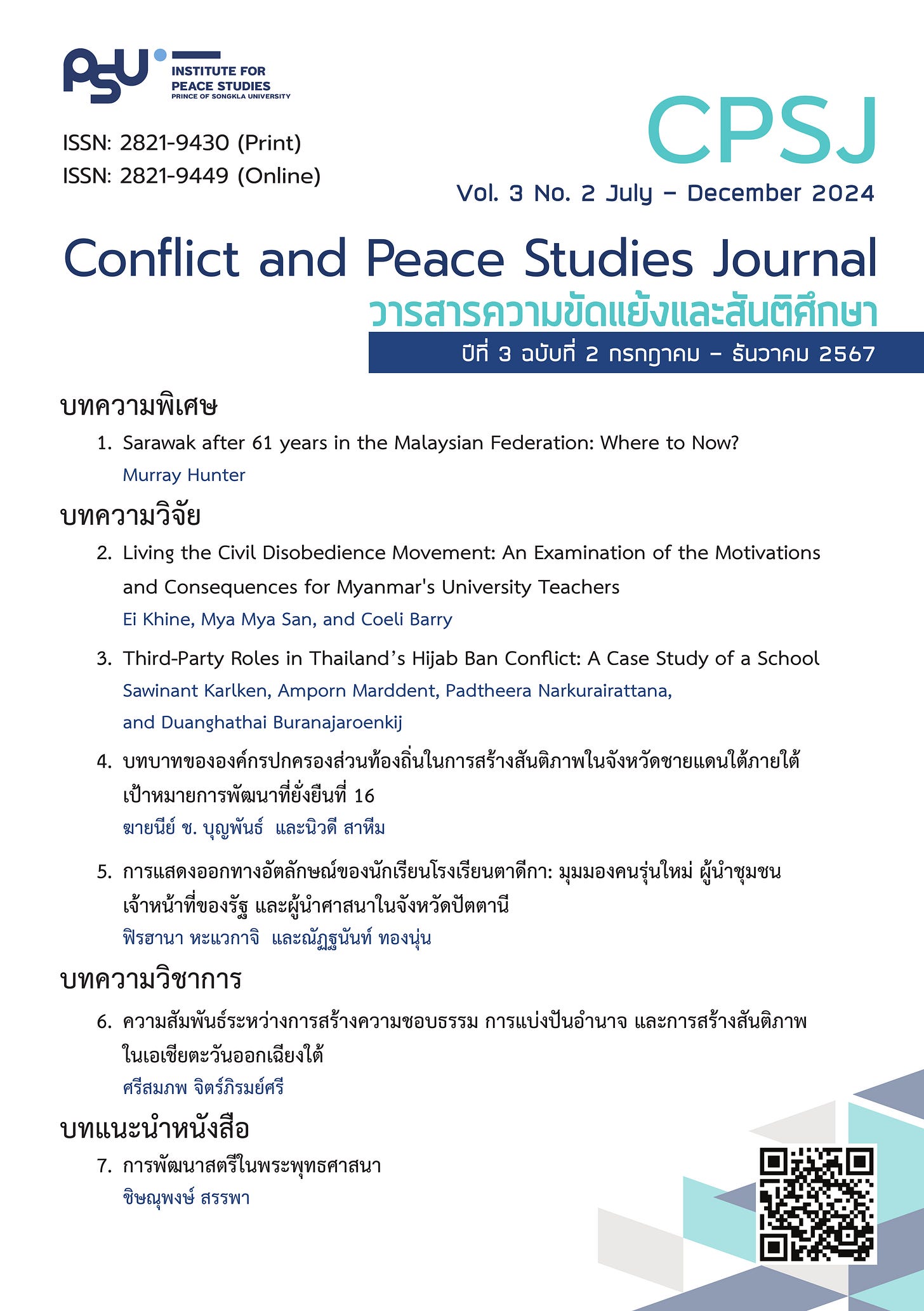

You can access the Journal of Conflict and Peace here

Abstract

Sarawak was thrust into a federation, along with Malaya, Singapore, and Sabah (Noth Borneo) on September 16, 1963. Sixty-one years later, Sarawak finds itself still reconning with history, due to continued negotiation with Putra Jaya on the Malaysia Agreement (MA63), and a cultural and political void between itself and peninsula Malaya. There are now a number of contentious issues between Sarawak and Putra Jaya, plus a rebound in Sarawak nationalism which are shaping the region’s future directions. This article will look at these issues and canvas aspirations for further governmental autonomy and/or eventual independence from Malaysia.

Part 1: The past makes the present

On September 4, 1841, the land extending from Tanjung Datu to Samarahan River in north-west Borneo was ceded as a reward by Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin of Brunei to James Brooke. Brooke became Rajah and governor for suppressing the rebels against the Sultan of Brunei. The expansion of Sarawak to today’s borders was secured in successive stages with the takeover of Brunei’s territories by the second Rajah Charles Brookes, taking in the districts of Lawas and Limbang by 1917.

The land, known as Sarawak, recognized by the United States in 1850, and Great Britain in 1864, is bordered by Indonesian Kalimantan to the south, Brunei and Sabah to the east, with the shores of the South China Sea running along the north of the territory. In 1888, Great Britain and Sarawak signed a protectorate treaty.

In 1867, a legislative council, formally called the Sarawak General Council was established by Rajah James Brooke in the small fishing village of Bintulu, with 5 British officers, 16 Malay and Melanau community leaders, and Rajah Brooke as the president.

The third Rajah Vyner Brooke in 1941 proclaimed the Sarawak Constitution, with Nine Cardinal Principles[1] to mark a century of Brooke rule. The aim was to prepare Sarawak for self-rule, where power from Rajah Brooke would be eventually be devolved to the people of Sarawak, as a secular, democratic, and pluralist state.

After the Japanese occupation ended in 1945, the British had planned to consolidate all British colonies in the Malay-archipelago, into what was described as the Malayan Union. With Sarawak’s treasury practically empty after the war, Rajah Vyner Brooke was ‘convinced’ to cede the sovereignty of Sarawak to the British, even though there was already a long-standing protectorate agreement. Amid protests by representatives of the indigenous people, Sarawak[2], became a crown colony on May 17, 1946.

This wasn’t accepted very well by a number of native teachers and civil servants of Sarawak, who expressed their disappointment through organized protests against cession of Sarawak to the British. This cession of Sarawak was denounced, where the restoration of an independent state under Rajah Brooke was demanded. This led to mass resignations from the civil service in what is now called ‘338’ (the number of native civil servants who resigned).

Civil unrest climaxed on December 3, 1949, where the and commander-in-chief Governor Sir Duncan Stewart was assassinated in Sibu. The two youths that were involved in Stewart’s assignation were convicted of murder and hanged along with two other conspirators[3], who were believed to be members of a political group, aiming for union which the newly independent Indonesia (Thomson 2016).

The United Nation’s stand against colonialism, and the need for the British to let go of its colonies in the ‘Far East’ by United Nations pressure, eventually led to the independence of Malaya on August 31, 1957, after lengthy negotiations with Tunku Abdul Rahman and group of multi-ethnic leaders. Similarly, negotiations by the British in Singapore, Sarawak, Brunei and North Borneo (no Sabah) continued.

Moving forward to 1962, the Committee for Greater Malaysia or the Cobbold Commission of Inquiry was well aware of opposition to the formation of Malaysia by natives and some political parties[4], although this was not made clear in the final report. The commission heavily supported the positions of the Malayan prime minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, and the chief minister of Singapore Lee Kwan Yew.

There was great concern that the Borneo territories were not ready for self-government, and lacked respect for the rule of law. The members of the Cobbold Commission believed that ‘one man one vote’ in the Far East has not been a wild success, especially with unsophisticated peoples. Subsequently, no plebiscite in North Borneo or Sarawak was ever undertaken.

The Commission made the conclusion that the entry of North Borneo and Sarawak into Malaysia would be in the territories’ best interests. The Commission report had the firm belief that those groups in North Borneo and Sarawak opposed to a merger would eventually dissipate (Cobbold Commission, 1962).

The report ignored the strength of the anti-Malaysia campaign. The Sarawak United Peoples Party (SUPP) had a membership of 41,386 scattered across Sarawak, with a primary platform to create a sovereign independent nation. Many minority groups feared the domination of a Malaysia by the Malays[5]. The monarch of the nation Malaysia would never come from Sarawak, the national language Bahasa Malaysia, and Islam as the state religion ran all against the tenets of life for a great majority of Sarawakians.

Any independence by merger into Malaysia would not be regarded as any fulfilment of the aspirations of the people for independence. It would merely be a transfer of political power from Great Britain to Malaysia, a continuation of colonialism.

SUPP had concerns that any Malaysian military house more than 300 miles away across the South China Sea would not be adequate in protecting Sarawak. Sarawak could easily make alternative security arrangements with Great Britain (like Brunei later did). In addition, Sarawak had been economically sufficient on its own for hundreds of years, and didn’t need to be part of a greater Malaysia.

Consequently, the Malaysia agreement was considered by SUPP to be detrimental to the interests of the peoples of Sarawak. Moreover, the pledge made by the Crown when Sarawak was ceded to Great Britain by Rajah Brooke, was for Britain to uphold the 1941 Sarawak Constitution and Nine Cardinal Points.

SUPP submitted a memorandum to the Cobbold Commission in the form of a petition, signed by 114,000 Sarawakians[6]. This was supported by public meetings opposing the merger all over Sarawak, which was not reported in the Cobbold Commission Report. Tunku Abdul Rahman took the opportunity to paint SUPP as a communist influenced organization.

In December 1962 after uprisings in Brunei, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III, decreed that Brunei would not join the Federation of Malaysia. In Sarawak, British authorities, undertook a country-wide sweep, leading to the arrest and detention of 6,000 ‘subversives’ suspected of being against the formation of Malaysia. Around 1,500 youths fled across the border to Kalimantan, Indonesia to begin a guerilla war of liberation.

On July 22, 1963, Sarawak’s first chief minister Stephen Kalong Ningkan, was sworn in by the Governor Sir Alexander Waddell. Five Assembly members were then sworn in as council members. This was self-government, but has been reframed as pseudo independence (The Borneo Post, 2015) by the former chief minister, the late Adenan Satem in 2016. The day has been officially gazetted as a holiday, which became known as ‘Sarawak Independence Day’ (Goh, 2016).

Just before the formation of Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines requested that the support of the people of the Borneo territories be ascertained by an independent and impartial authority, through a referendum, by the United Nations. A nine person UN Mission travelled to Kuching in August 1963, and was met by demonstrations against the merger into Malaysia. The UN group saw signs of resistance to the merger all around Sarawak as they travelled. The UN team on September 2, reached the conclusion, based upon a ‘grassroot survey’ that the people of Sarawak were pro-Malaysia[7]. It found little evidence of articulate and organized opposition to the Federation, which quelled Indonesian and Philippine disquiet.

The proclamation of Malaysia didn’t achieve the August 31 target to coincide with Malayan independence day, and the Federation of Malaysia came into being on September 16, 1963. According to a telegram dated August 21, 1963 Tunku Abdul Rahman caused resentment in both Jesselton (now Kota Kinabalu) and Kuching on the news that Sabah and Sarawak would only be states in the new Federation, alongside the other states in the peninsula[8].

Part 2: The Kuching-Putra Jaya relationship today

After 61 years in the Malaysian Federation, Sarawak has contributed more to the nation’s revenue, through oil and gas, than it has received. While the peninsula is almost fully developed with a good road system, and modern infrastructure, Sarawak’s roads and infrastructure outside of major towns is very poor. In terms of absolute poverty, Sarawak ranks third in Malaysia, after Sabah at 19.5 percent, Kelantan at 12.4 percent, and Sarawak at 9 percent, on 2019 figures (Koh, 2023).

To Sarawak’s benefit, the historical, demographic, language, and cultural differences with the peninsula have spared the territory the race tainted political and Islamic fervour, wrapped up in Malaysia nationalism or Ketuanan Melayu. Such politics is not practiced in Sarawak. Peninsula based political parties only hold two seats in the Sarawak State Assembly.

Unlike Sabah, where migrants were assisted in a clandestine program, in what was dubbed “Project IC” to assist on influencing elections, Sarawak with a population of 2,907,500 (at 2020) is largely unaffected by migration, except from Kalimantan, where the culture is similar. There is an estimated 138,027 foreign workers from Indonesia, Philippines, Myanmar, China, and India, under a controlled immigration program (Lumayang, 2020).

Dr Johan Ariffin Samad, the former executive director of the Sabah based think tank Institute of Development Studies (IDS) said in a CNA interview that “the two states (Sabah & Sarawak) have been relegated to the sidelines of the nation’s decision-making process” (Aqil and Bedi, 2024). Samad felt there was a blatant disregard of the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63), the legal document that forms the basis of the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. Sarawak’s Parti Bumi Kanyalang (PBK) president Voon Lee Shun puts the above argument much stronger when he says “Sabah and Sarawak and are in-fact ‘colonies’ of Malaya, and Malaya is in control of power – education, health, Government service, economy, social life, politics and Religion” (New Sarawak Tribune 2021).

The major source of contention between Kuching and Putra Jaya has been the MA63. The MA63 guarantees autonomy for Sarawak, but there is disappointment by some professional and educated people, that this was not honoured by the Federal Government, over the last 61 years.

The MA63, recognises Sabah and Sarawak as equal partners with Malaya in the formation of Malaysia, but Sabah and Sarawak have been treated as mere states. Article 1 (2) of the Malaysian Constitution still lists Sabah and Sarawak as states, alongside other states in the Peninsula.

Negotiations on MA63 between Sabah, Sarawak and the Federal government are ongoing, where both Sabah and Sarawak want increased financial autonomy, with a 40 percent share of revenue collected, and a much larger number of seats in the current 222 member Dewan Rakyat or lower house. Currently, Sabah has 25 seats and Sarawak 31 seats. This is perhaps one of the very few issues Sabah and Sarawak are politically unified on the point of wanting Borneo to have 35 percent of the seats in the Dewan Rakyat.

Other contentions with Putra Jaya concern control of the continental shelf of Sarawak. Currently, Sarawak has rights over a 3 (5.3km) nautical mile limit from the shores, where the Federal government controls the rights the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) reaching 200 nautical miles (371km) from shore. At stake are oil and gas reserves and future revenues. Sarawak possesses at least 800 million barrels of proven oil reserves, with recent discoveries extending this figure greatly. This accounts for more than 60 percent of Malaysia’s oil and gas reserves. Sarawak’s Premier Abang Johari Openg has given The Malaysia national oil and gas producer until October 1, 2024 to come to an agreement with Sarawak. At the time of writing, Petronas is seeking a court injunction to delay the deadline (Battersby 2024).

Sarawak holds 90 percent of Petronas gas stocks, and the Sarawak state-owned Petroleum Sarawak Berhad (Petros) is now the sole gas aggregator, pushing Petronas out of buying and selling gas in Sarawak.

Sarawak is relying upon a state law, the Oil and Gas Mining Ordinance 1958, which was passed before the formation of Malaysia in 1963. The Sarawak government is claiming this law is still in force. The federal government has left this issue to Petronas to settle.

A change in the balance of power nexus

In November 2022, the balance of power dramatically changed between Kuching and Putra Jaya after the last general election. With the general election resulting in a hung parliament, the first of its kind in Malaysian federal election history, the support of Sarawak’s Gabunan Parti Sarawak (GPS) coalition with 23 parliamentary seats was necessary to create a stable federal administration under prime minister Anwar Ibrahim.

This forced Anwar, to make a number of concessions to the Borneo parties. For the first time in federal history, a deputy prime minister position was given to Fadillah Yusof, a member of Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB), a member of the GPS coalition. Ten out of 43 minister came from Borneo (8 from Sarawak), and 13 out of 35 deputy ministers (6 from Sarawak) came from Borneo. This gave the Borneo parties, particularly Sarawak an unprecedented position in the federal government in recognition of being the kingmaker in the formation of the Anwar government.

Sarawak has not been slow to use its position to takeover powers and responsibilities at state level. With a perceptively weak prime minister, the current Sarawak state government has pushed back on a federal government directive to use Bahasa Malaysia in the civil service, and strongly stated that the Sarawak government would continue to utilise English as the official medium (FMT Reporters, 2024). Sarawak would also create its own school assessments (FMT Reporters (a) 2024), and is on-track to provide free higher education at Sarawak owned universities in 2026 (Tawie, 2024).

In addition, Sarawak has taken over an airline MASwings to begin operations at the end of 2024 (Curran, 2024), finalising conditions for the takeover of Bintulu Port from the Federal Government (Tawie (a), 2024), and negotiating the purchase of Affin Bank (Bernama, 2024) to specifically serve the needs of Sarawak. Under Sarawak’s own immigration jurisdiction, the state has developed its own expatriate migration program, called Sarawak Malaysia My Second Home (MM2H) to compete with the Federal program to attract expatriate retirees (Ling, undated).

Such initiatives would have not been possible under previous federal governments. Political analysts differ on their views about how far the Sarawak government can push the current Anwar administration, where one pundit believes the recent pledges of loyalty from six opposition Bersatu MPs to the government, would enable the Anwar administration to survive anymore pressure from Abang Johari’s government in Kuching (annon., 2024).

Part 3: The way ahead for Sarawak

Many consider the MA63 agreement the major stumbling block between Kuching and Putra Jaya. Lina Soo, President of the Sarawak People’s Aspiration Party (SPAP) describes the MA63 as “a broken mirror, which cannot be patched up to serve its purpose of providing a good reflection”, metaphorical of a broken-down relationship which can’t be healed or salvaged[9].

UMNO vice president Mohamad Hasan (Tok Mat) said a new Malaysia Agreement is the best approach to restore the rights and interests of Sabah and Sarawak (FMT, 2022). The Democratic Action Party mentor Lim Kit Siang went even further saying there should be a complete reappraisal of all federal-state relations, greater decentralization, and autonomy from Putra Jaya[10]. There have also been suggestions of Borneo having ‘veto power’ in some way or the other in the federal parliament (Sarawak Rose, 2024).

Such a new agreement, according to Soo would be far sighted and potentially change the dynamics between Sarawak and Putra Jaya. A new agreement may solve much political instability. This could be an opportunity for a new Malaysia that not just Sarawakians hope for[11].

Sarawak’s future options

There are three major options ahead for Sarawak;

1. No change, just stay the same

The vote on constitutional amendments and changing the status of Sabah and Sarawak from Negri or state to Wilayah or region is more symbolic than any great substance. What is more important are the MA63 discussions now ongoing.

However, the inertia for the status quo is now being challenged by the Sarawak state government itself. The moves it has been taking over the last couple of years indicate this. Increased pressure by PBB on peninsula based political parties like Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) and the Democratic Action Party (DAP), which holds two state seats not to run in the coming Sarawak state election, due in 2026 is increasing.

Issues that prevent Sarawak further developing economically are additional push factors against the inertia of just staying the same.

A major structural problem is the domestic economy. The local economy lacks enough diversity to provide sufficient jobs for Sarawak’s youth. This forces Sarawakians to travel to the peninsula or Singapore in search of jobs, due to lack of industry, and well-rounded and growing agricultural and SME sectors. In addition, lack of agricultural development beyond corporate owned plantations brings food security issues to Sarawak (Rosni & Hunter, 2014, pp. 23-30).

Sarawak lacks competitive merchant shipping to enable the state trade with the rest of the world. A National Cabotage[12] policy was introduced into Malaysia in the 1980s, mandating all ships plying Malaysian ports must be registered in Malaysia, where foreign vessels cannot off-load or on-load cargo except in Port Klang in the peninsula. The need to trans-ship goods greatly stifles the potential future economic growth, due to these increased costs. Exports and imports into and out of Sarawak are unnecessarily expensive, preventing both the development of a domestic private economic sector and international trade (Wong PPM, 2023, P. 39).

“No change, just staying the same” will depend on Sabah and Sarawak remaining as “king makers” in federal politics. This will greatly depend upon whether the Malay vote remains split between Perikatan Nasional (PN) and Pakatan Harapan-UMNO in the next federal election due by 2027.

2. Secession-independence

The nomenclature, secession or independence, depends upon one’s interpretation of history, something beyond this review. Much has been written about this subject. An independent Sarawak would remain just a romantic sentimental notion, unless the economics can be substantiated. Only a small number of urban middle-class and professionals inside of Sarawak strongly support the secession option, fuelled on by a vocal diaspora domiciled in cities like London, Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide.

In addition, national defence must now be considered a major issue with the Chinese Coast Guard regularly in Sarawak’s waters (Bernama (a), 2024).

Another factor would be the potential damage done to the Sarawak economy if a Trump presidency resulted in crippling tariffs on Malaysia for assisting Iran (Hunter 2024).

Moves towards independence and leaving the Federation of Malaysia would revive the anguish of the Malayan elite in the loss of Singapore, when it left the federation in 1965. The Malay rulers would exercise a great say on this issue, and its uncertain what their views would be, thus taking any decision away any final decisions from the politicians. Any attempt of Sarawak to leave the Federation could lead to a violent road, which would be met with hyped up security surveillance, and suppression. The symbolic deployment of the Royal Malaysian Army 10th Rangers in Kuching attests to this, and is a constant reminder to Sarawakians.

Any independence would presumably occur after an exercise of self-determination, ideally an independent referendum with international observers. However, even if this currently unimaginable scenario occurred, achieving a positive vote for secession from the federation, referred to as “Sarexit”, would not be straight forward for the reasons mentioned above. It would be doubtful Putra Jaya would recognise any positive result for leaving the federation.

The elephant in the room

Any secession from the Malaysian Federation would be purely futile if the same Melanau elite rule Sarawak. PBB with its coalition partners garnered 62.2 percent of the popular vote in the last state election.

There are very close patriarchal political relationships across Sarawak through all levels of government and the judiciary. Many are the result of family and clan ties. Sarawak has its own version of Ketuanan Melayu or Malay nationalism, being redefined as “Ketuanan Malanau”, or Melanau dominance in government. This is evident in the Sarawak civil service. To some degree the Dayaks and Ibans and other minority groups are subservient to the Malanau and Brunei Malays.

Thus, what is probably more important for Sarawak today is developing a more inclusive notion of politics, democracy and governance. Indigenous sovereignty of tribes in the deep inland areas of Sarawak is another major unreconciled issue. Ancestorial and tribal lands are continuing to be leased to ‘crony corporations’ with close connection to the Sarawak political elite. Historical injustices, discriminatory practices and a grossly inadequate share of state resources are issues to be overcome if there was ever to be any equitable independence.

The focus on Putra Jaya as the oppressor takes attention away from which group is the real “feudal lord in residence”. However, all is not black and white. GPS has been able to maintain the integrity of Sarawak much better than Sabah over the last 61 years. Sarawak is the only region in Malaysia not to have a state religion, and the only region to have pushed back on edicts from Putra Jaya.

This has been at the cost of what ‘Marxists’ would call a lumpen bourgeoisie in Sarawak, made up of connected people who have accepted roles in government, serving the interests of the elite who put them there. This creates a system of privilege, patronage, nepotism, and exclusion, and an environment of exploitation.

The question for political scientists in the future is which is best, an ethnically and politically concentrated government that is strong-minded about the mission, or an inclusive government that continually bickers over issues? These are ‘value judgement’ arguments.

3. Greater autonomy

The relatively weak position of the prime minister Anwar Ibrahim towards Sabah and Sarawak today, due to his need to keep the federal coalition intact, has allowed Sarawak to gain greater autonomy over the last 18 months.

However, autonomy itself is a wide continuum which in the extreme would mean Putra Jaya would be restricted to looking after defence and foreign policy, and the Sarawak government responsible for all other matters. This would imply an extremely complex revenue agreement, which would take a long time to negotiate and implement.

Greater autonomy is the most likely pathway for Sarawak, where the current state government and many ‘activists’ see as a realistic alternative in the future – “a state within a state” solution. This is an option that requires imagination, education, and negotiation on reaching a vision in both government and the people of Sarawak could share. However, this is where it becomes a naivety to think such collaboration could possibly occur.

In addition, one of the collateral spillovers of Sarawak autonomy is that it will lead to a ‘chain reaction’, where more states would seek the same or similar degrees of autonomy. Sabah would be next, with Kelantan and Terengganu following suit. Johor and Penang would also have aspirations for more autonomy. This would completely redraw Malaysia’s current nexus of federal-state relations, which have been in the federal government’s favour for the last six decades.

Attitudes of the Sarawak Government

What is important is the attitude of the state government, which is controlled by GPS coalition, made up of three parties, Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB), Parti Rakyat Sarawak (PRS), and Sarawak United Peoples’ Party (SUPP). All three parties are Sarawak-centric, receiving 62.2 percent of the vote at the 2021 state election.

A very senior figure within PBB told the author that seniors within the party believe Sarawak cannot go alone, and fundamentally must remain in Malaysia (mainly security and economic reasons), but with maximum autonomy and little interference in state affairs from Putra Jaya[13].

The prime disenchantment with Putra Jaya is over oil revenue issues, which appear to encourage official resurgences in calls for more autonomy from time to time. Counterintuitively, GPS abstained from voting on a constitutional amendment to restore Sabah and Sarawak as equal partners back in 2019 for domestic political considerations (Ling, S, 2019).

Sarawakians still need more deployment of basic education that reaches deep into the interiors, so people can understand the issues involved in civics and community. The reinstatement of local elections would widen the scope of future discussion, and provide new leaders from diverse backgrounds. Democracy must be opened up at the grassroots and nurtured up the hierarchy of governance to give a real sense of what Sarawakian’s really think and how their destinies should be intertwined.

There are those who feel that Sarawakians have been betrayed by many parties through history and they have been prevented from sovereignty, once guaranteed to them by Clause 7 of the Nine Cardinal Principles in the preamble of the 1941 Sarawak Constitution which read “The people of Sarawak shall be entrusted in due course with the governance of themselves, and that continuous efforts shall be made to hasten the reaching of this goal by educating them into the obligations, the responsibilities and privileges of citizenship.”

Then questions can be asked about what Sarawak should look like in the future. How should Sarawak be governed? Should Sarawak focus on development? If so, what type of development? Should Sarawak focus on maintaining cultural integrity? Should Sarawak open up to the world, or maintain a sense of isolation?

These are all questions for the next generation.

Originally published in the Journal of Conflict and Peace Studies

Subscribe Below:

References

Annon. September 8, 2024, Abang Jo’s Luck Is Running Out – Part 2, Malaysia Today, retrieved September 23,2024, https://www.malaysia-today.net/2024/09/17/abang-jos-luck-is-running-out-part-2/

Aqil Haziq Mahmud and Bedi, R. S. September 14, 2024, IN Focus: Push for greater autonomy by Sabah and Sarawak is stronger than ever, but will they finally succeed?, CNA, retrieved September 21, 2024, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/malaysia-sabah-sarawak-autonomy-ma63-anwar-

Battersby, A., September 11, 2024, Petronas mulls court injunction as Sarawak seeks greater control over hydrocarbon assets: Report, Upstream, retrieved September 21, 2024 https://www.upstreamonline.com/politics/petronas-mulls-court-injunction-as-sarawak-seeks-greater-control-over-hydrocarbon-assets-report/2-1-1707401

Bernama, September 21, 2024, Sarawak to announce Affin Bank deal within a week, FMT, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/highlight/2024/09/21/sarawak-to-announce-acquisition-of-affin-bank-within-a-week/

Bernama (a), July 24, 2024, Mindef to probe China coast guard’s presence in S’wak waters, says Khaled, FMT, retrieved August 12, 2024, https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2024/07/28/mindef-to-probe-china-coast-guards-presence-in-swak-waters-says-khaled/

Cobbold Commission, (1962), Report of the Commission of Enquiry, North Borneo and Sarawak, Chapter 3, pp. 55-56, retrieved at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Report_of_the_Commission_of_Enquiry,_North_Borneo_and_Sarawak,_1962/CHAPTER_4/general_matters 20th September 2024.

Curran, D., April 15, 2024, Sarawak Premier still bullish on 2H24 takeover of MASwings, ch-aviation, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.ch-aviation.com/news/139212-sarawak-premier-still-bullish-on-2h24-takeover-of-maswings#:~:text=Sarawak%20State%20Premier%20Abang%20Johari,transport%20ministry%2C%20the%20Malaysian%20Aviation

FMT, July 5, 2022, Just a suggestion, Tok Mat says after New Malaysia agreement idea criticised, FMT, retrieved May 16, 2024, https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2022/07/05/just-a-suggestion-tok-mat-says-after-new-malaysia-agreement-idea-criticised/

FMT Reporters, January 1, 2024, Sarawak may takeover other major entities this year, says Abang Jo, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2024/01/01/sarawak-may-take-over-other-major-entities-this-year-says-abang-jo/

FMT Reporters (a), July 12, 2024, Sarawak won’t be pressured to reduce use of English, says deputy minister, FMT, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2024/07/12/sarawak-wont-be-pressured-to-reduce-use-of-english-says-minister/

Goh, Pei Pei, May 26, 2016, Public Holiday for Sarawak July 22, New Straits Times, retrieved September 21, 2024, https://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/05/147981/public-holiday-sarawak-july-22

Hunter, M. July 19, 2024, Malaysian Trade under a Trump presidency, Murray Hunter Substack, retrieved July 19, 2024, https://murrayhunter.substack.com/p/malaysian-trade-under-a-trump-presidency?publication_id=347364&utm_campaign=email-post-title&r=7va4z&utm_medium=email

Koh, S. (2023) Population under the Poverty Line, retrieved September 22, 2024, https://sdg-for-malaysian-states-sdsn.hub.arcgis.com/pages/sdg-1-indicator-121-population-under-national-poverty-line

Ling, A. The insider’s guide to Sarawak-Malaysia My Second Home (Sarawak MM2H), MM2H, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://officialmm2h.com/sarawak-mm2h/

Ling, S, April 10, 2019, Rohani: GPS MPs abstained from voting as constitutional amendment needs more study, The Star, retrieved May 10, 2024, https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/04/10/rohani-gps-mps-abstained-from-voting-as-constitutional-amendment-needs-more-study/

Lumayang, L. (2020) Foreign Labour Migration in Sarawak, East Malaysia: Labour migration in Sarawak Malaysia, International Migration, 58 (8), retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340068287_Foreign_Labour_Migration_in_Sarawak_East_Malaysia_Labour_migration_in_Sarawak_Malaysia

New Sarawak Tribune, 2021, Greater autonomy for Sabah, Sarawak doubtful, New Sarawak Tribune, February 7, 2021, retrieved September 21, 2024, https://www.newsarawaktribune.com.my/greater-autonomy-for-sabah-sarawak-doubtful/

Rosni, B, and Hunter, M., (2014), The Development and Marketing Strategies for Local Products of Sarawak, Kuching, Unit Pembangunan Usahawan Bumiputera (UPUB), Chief Minister’s Office, Government of Sarawak.

Sarawak Rose, September 22, 2024, Comment: Veto power for East M’sia in Dewan Negara, Malaysiakini, retrieved https://www.malaysiakini.com/columns/720056

Soo, L. (2013), Sarawak: The Real Deal, 2013, Kuching, Self-Published.

Tawie, S. July 27, 2024, Sarawak on track to provide free higher education for qualified Sarawakians by 2026, NST, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2024/07/1082498/sarawak-track-provide-free-higher-education-qualified-sarawakians-2026

Tawie, S. September 20, 2024, Bintulu Port takeover: Compensation to federal government still under review, retrieved September 23, 2024, https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2024/09/1108187/bintulu-port-takeover-compensation-federal-government-still-under-review

The Borneo Post, November 9, 2015, July 22, 1963 not the day Sarawak gained independence — Prof Leigh, The Borneo Post, retrieved September 20, 2024, https://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/05/147981/public-holiday-sarawak-july-22

Thomson, M. (2012), The stabbed governor of Sarawak, BBC, retrieved August 17, 2024, from https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-17299633

Wong, P. P. M. (2023), Why Independence is Sarawak’s Best Option: Strategies to develop Sarawak independently of the federal government, Kuching, Self-Published.

[1] See Nine Cardinal Principles reprinted in Sarawak: The Real Deal (2013), vi.

[2] See letter to Raja Muda Sarawak in in Sarawak: The Real Deal (2013), P. 9.

[3] In 1975, the name of SMK Bandar Sibu School in Sibu was changed to SMK Rosli Dhoby in commemoration. Rosli Dhoby’s remains were removed from Kuching Prison to Sarawak’s Heros Mausoleum in Sibu in March 1996, where he was given a State Funeral by the Sarawak Government.

[4] See assorted letters and declassified documents, in Sarawak: The Real Deal (2013), pp. 14-54.

[5] Sarawak is the only state or territory in Malaysia where Islam is a minority religion.

[6] The total population of Sarawak at the time was 745,000.

[7] See assorted letters and declassified documents, in Sarawak: The Real Deal (2013), P. 109.

[8] See assorted letters and declassified documents, in Sarawak: The Real Deal (2013), P. 118.

[9] Private communication.

[10] Private communication.

[11] Private communication.

[12] Cabotage laws apply to merchant ships that have a coastline and want to protect the domestic shipping industry from foreign competition.

[13] Private communication.