Skills, personal competencies and enterprise capabilities throughout the organization lifecycle

Various factors have been put up as reasons that can explain performance

1. Introduction

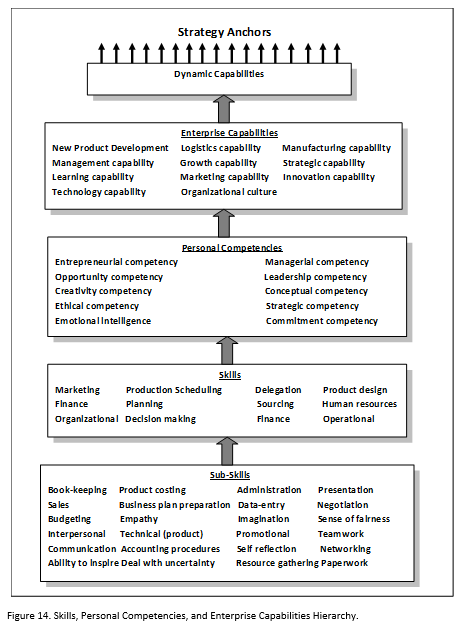

Over the last few decades of entrepreneurial research, various factors have been put up as reasons that can explain performance. However the results of these studies have shown insignificant correlations with performance (Begley & Boyd 1985, Perry et al. 1988) or been inconsistent (Chandler & Hanks 1994, Cooper 1993). The entrepreneur's skills and competencies and their effect on firm capabilities and performance seem to take on more importance (Man et al. 2002). Skills and competencies can be seen as being more behavioral than personality traits, intentions, or motivations (Bird 1995). A person's skills and competencies will reflect more upon behavior and the firm's capabilities and effectiveness than other factors, laying the bedrock of strategy development. Success depends upon a firm maintaining not just a focus upon the external environment, but also focusing on the internal organization to ensure it has the resources and develops the capabilities to exploit, and to continue to exploit, the perceived opportunities in the environment (Lipparini and Sobrero 1994). Without skills and personal competencies a firm will have few capabilities. It is these capabilities that create firm effectiveness and underline the strategies that create competitive advantage form the firm.

This article will examine the difference between basic abilities, skills, talents, and expertise, then look at the basic skills required to undertake the various tasks required in a firm, look at the development of personal competencies and how they relate to enterprise capabilities that form the anchors of strategy.

2. Abilities, Skills, Talents, and Expertise

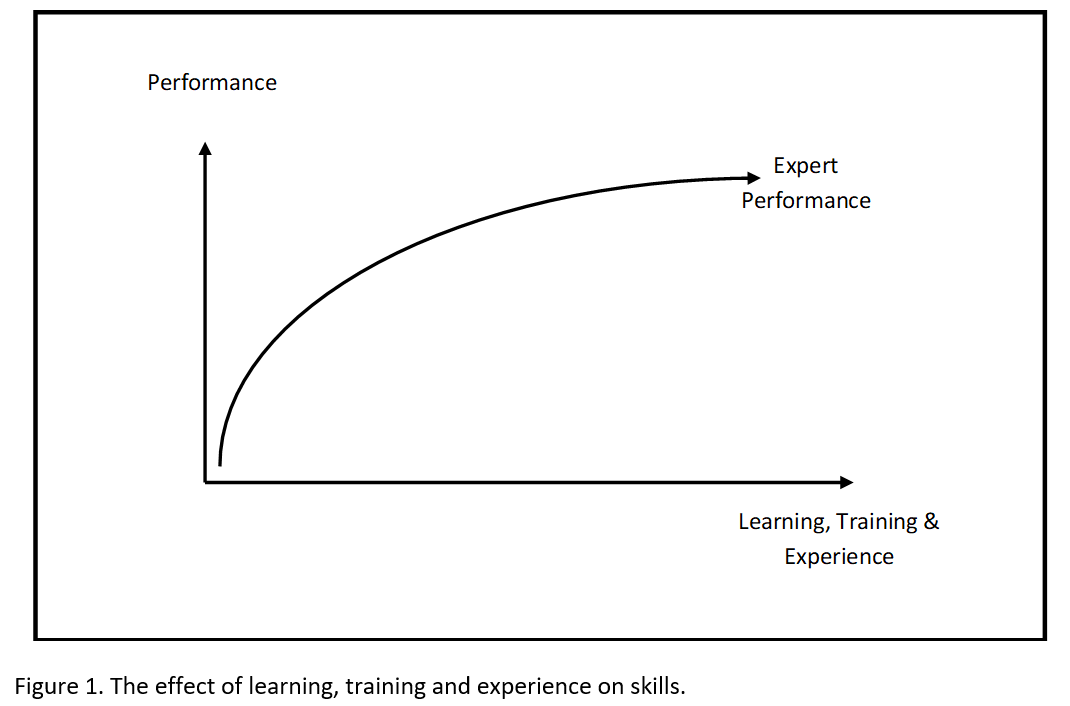

People are born with particular abilities or natural talents. A natural ability is an innate aptitude towards some kind of physical or mental tasks. Ability is natural skill or talent, a qualitative personal attribute that enables some exercise of personal capability. A natural ability is a person's existing or raw capacity to perform various tasks with no or very little education, training, or experience. (1) These may include physical activities like running, swimming, gymnastics, or ball game coordination, i.e., selected bodily-kinaesthetic activities. They may also include mental tasks like mental arithmetic and picking up language vocabulary, i. e., selected cognitive activities. We may also inherit psychic abilities like empathy, intuition, spirituality, etc. (Eysenck 1995). However, although people may possess natural attributes, only hard work, learning, training and experience can develop these into an expertise (Renzulli 1978) (see Figure 1).

Therefore people with inherent abilities can only take them so far without developing proficiency through knowledge and practice. Abilities are only innate traits and dispositions that need to be developed before they can become skills. As skills are acquired behaviors, they need a willingness, desire or conditioning (2) to learn. Skills are therefore a learned capacity to translate knowledge into action that results in desired outcomes or results, with a minimum amount of predetermined thinking. Skills turn knowledge as theory into practice. For example, an MBA graduate may understand the theories of marketing, the product concept, market positioning, segmentation, strategy, advertising and promotion, and consumer behavior, etc. All this is knowledge and it is translated into practice through skill, just as learning to drive a car or fly an aircraft. And to a certain degree, learning requires a time of trial and error to become proficient, which is experience. Therefore skills rely on both education and experience.

Skills rely on a great amount of intuition when being translated into action. Car mechanics, computer technicians, automobile and train drivers, pilots, and athletes rely greatly on intuition to get their jobs done. Good intuition based on skills and knowledge builds skills into expertise. Expertise requires a large amount of domain-specific knowledge. Simon and Gilmartin (1973) estimated that about 50,000 chunks are needed to become an expert in a particular fields and this accumulation of knowledge would take many years. (3) Sternberg (1998) argues that expertise is a combination of genetic endowment (abilities) and experience, and among its important characteristics are:

* Rich schemas containing large amounts of declarative knowledge that is domain specific,

* Spending time looking at problems and potential routes for solutions,

* Being able to develop rich representations to compare structural similarities of problems,

* Having schemas that contain procedural knowledge about solving problems (intuition),

* Being able to automate sequences of steps in problem solving procedures, and

* Being able to monitor problem solving strategies for effectiveness.

Skills can be developed into skill-sets that contribute to a person's competence. Personal competencies refer to underlying individual characteristics like knowledge, experience, and skills required in performing specific tasks (Baum 2001). For example, a person with a skill for football may have a complementary set of kinaesthetic skills for ball handling, athletic skills, coordination skills, etc., and cognitive skills that are spatial and strategic, etc. Any skill alone will not make a talented footballer, but combined these skills compose a person's expertise.

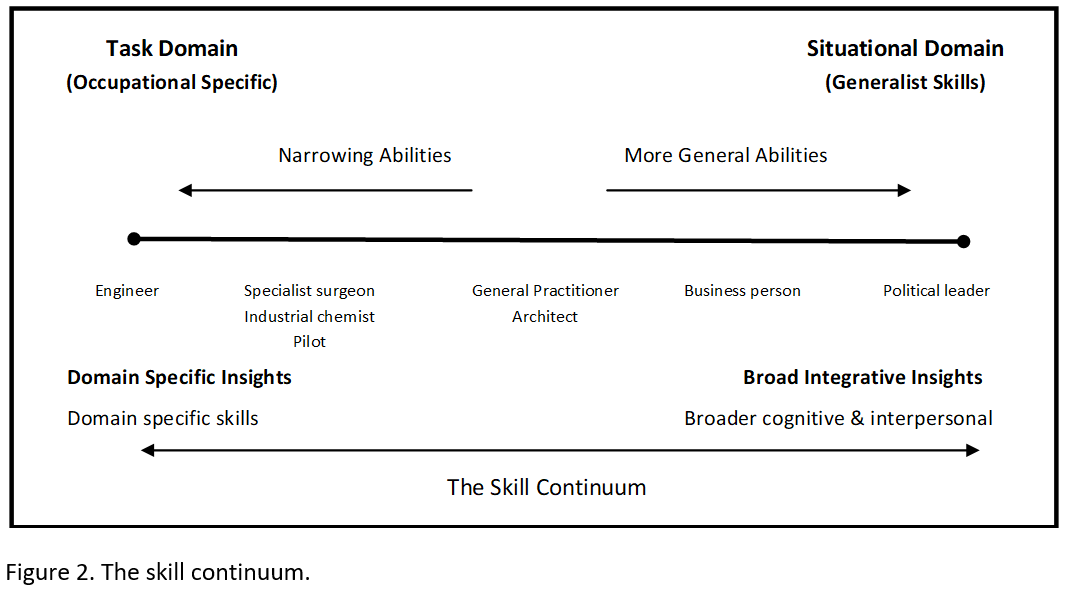

Skills fall along a continuum from very specific domain skills that can only be utilized in a specific job, to generalist skills that can be utilized in almost any job or situation. Various occupations can be placed along this continuum according to the types of skills required to undertake their jobs. For example, a design engineer working on designing very specific parts or products with well defined functions, materials, and other specifications. The knowledge and skills required to undertake this is very domain specific and skills, i.e., software skills, knowledge of material specifications, etc. Specialist surgeons, industrial chemists and pilots also carry a range of very specific occupational skills. However they also rely on some generalist skills to make decisions upon. Although their jobs are very specific, outside factors like the general condition of the patient, chemical properties, and weather conditions will influence specialist surgeons', industrial chemists', and pilots' decisions respectively. Further along the continuum, a general practitioner can look at a patient's symptoms, which may be common to many forms of disease. But it is usually the situational aspects of the patient, i.e., lifestyle, stress levels, etc., that leads the general practitioner to early conclusions. Likewise an architect must take account of the topography, weather, and surrounding environment when designing a new dwelling or building. Next along the continuum are business people who utilize specific skills, but rely on their knowledge, experience, and general skills to make decisions. The political leader almost entirely relies upon generalist skills to integrate all the elements he or she must deal with when making decisions.

At the left hand side of the continuum (see Figure 2), specific domain knowledge, skills, and expertise contribute to domain specific insights. For example a car mechanic will usually know from the sound of an engine what might be wrong with a car. To achieve these insights only select knowledge and expertise is required. On the other side of the continuum, insights are much broader and rely on multiple sources of information, wide areas of knowledge, experience, and a number of cognitive and interpersonal skills. For example, a skilled business negotiator (salesperson) or political leader will be able to pick up the emotions from his or her listeners and modify his or her approach to the audience.

Boyatzis (1982) found that there may be a relationship between personal competencies and organizational competencies (capabilities). Traits alone don't make entrepreneurs (Naffziger 1995), passion and enthusiasm are also required (Herron & Robinson 1993), and competitive strategies reflect the choices of people, whether they are an entrepreneur or manager (Child 1972). The choices will be based on what they are supposed to do, what they are motivated to do, and what they think they can do (Bandura 1986, Hollenbeck & Whitener 1988). People commit to strategies they think are achievable (Bandura 1986, Covin & Slevin 1997, Herron & Robinson 1993), but will only perform according to the limits of their own skills, abilities, talents and expertise (Bird 1989, Lock & Latham 1990). It should be also noted that different opportunities will require different sets of skills and competencies to exploit them.

3. Basic Business Skills

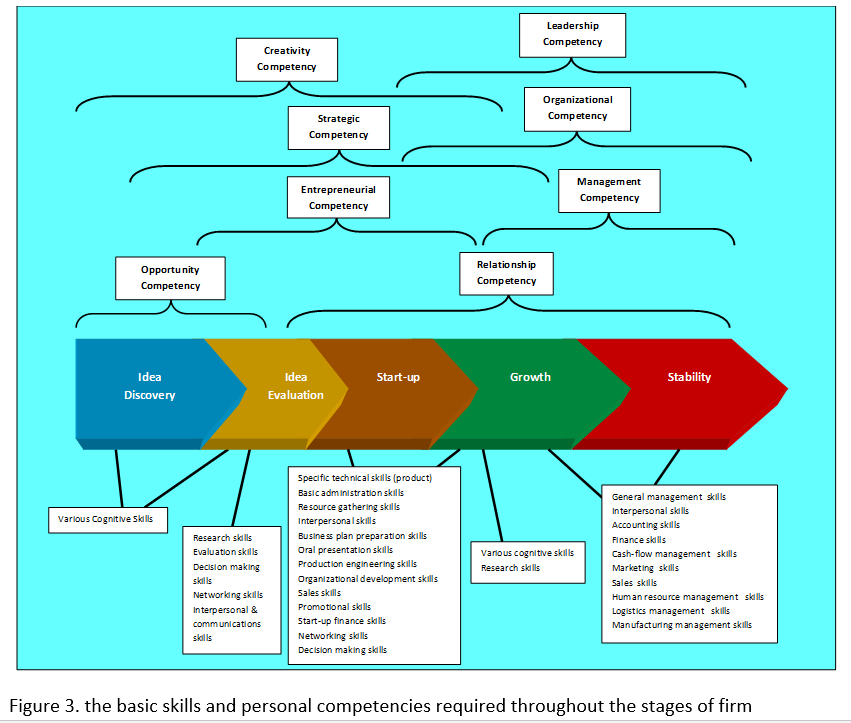

Basic business skills are necessary to underpin the vision of a firm, expressed in strategies and operations. Skills are needed to discover or construct ideas, evaluate ideas as opportunities, commence a start-up firm, develop products and services, market and sell products, and manage the firm through the early growth and maturity stages. During the infancy of a firm, a person's range of basic skills contributes to creating individual competencies which contribute to the firm's range of capabilities.

Different types of basic skills are required during the various stages of firm development. This is one of the challenges for an entrepreneur, as different problems require different skills to solve them (Churchill & Lewis 1983). Different skills can be synergized to form competencies to get things done, as individual basic skills by themselves are of limited use. Combining the knowledge behind different skills creates a much greater depth of understanding of tasks that can provide the intuition and eventually the wisdom required to make the important decisions, necessary in start-up firms. Figure 3 shows the basic skills and higher competencies required throughout the stages of firm development.

According to Robert Katz (1974) different types of skills have different relevance across different aspects of management. Technical skills deal with functional and specific specialized tasks, which are usually developed through education, training and experience. These skills enable a person to use select methods and procedures to accomplish tasks, i.e., software and computer skills. Technical skills are the most on the job and vocational of the three types of skills.

The second set of skills are human skills which enable a person to work with other people. They involve trust, enthusiasm, empathy, sensitivity, and the ability to communicate, which are central to many entrepreneurial activities and managing. These types of skills can be seen in the way a person works and behaves with others. These skills are used continuously when working with others. When a person is highly skilled in this area, he or she will be aware of their own attitudes, assumptions, beliefs and feelings. These skills are harder to learn formally as they tend to be integrated within a person's personality. However through some forms of training and self awareness human skills can be developed to some extent.

Thirdly, conceptual skills involve the capacity to see things as a whole, to understand interrelationships, and see new concepts, analyze and solve complex problems, coordinate, and identify new opportunities. The quality of decision making depends upon the quality of conceptual skills. Conceptual skills can also be looked at as a creative ability (Barnard 1948). More effort on the part of business educators has been put into teaching conceptual skills through experiential learning and simulations, etc. (4) Although these skills are much more abstract in nature, developing these types of skills have become the focus of leadership training, as it involves more about "ways of thinking".

Each type of skills can overlap with the other. For example, marketing skills which are functional technical skills require creative decision making which are based upon conceptual tools. This synergy brings out expertise, intuition and wisdom.

Any venture, event, journey, or project is the result of some form of idea that has been conceptually visualized and had the supporting motivation for a person to take action upon it. As we have seen, the creation of an idea partly comes from our prior knowledge fuelled by our life experiences which include employment experience (Basu & Goswami 1999), observation of the environment (Mitton 1989), social background (Basu & Goswami 1999, Murray 1996), hobbies and interests, networks, and personal histories (Murray 1996). These elements influence our emotions and what we think. We have also seen that opportunities created a number of ways through discovery or construction. We also know that the ability to generate ideas is not a uniform talent within the population and not all ideas are turned into actionable opportunities. Therefore generating ideas that are potential opportunities is a skill, and a cognitive one at that. As we all have the same cognitive hardware, it is the cognitive tools (ways we think) that are important skills in conceptualizing ideas. (5)

In the ideas evaluation phase of firm development, ideas need to be evaluated to determine their potential as an opportunity. The danger of failing to evaluate an idea fully may result in a person setting up a firm to follow a "dream strategy" in pursuit of a "fantasy" rather than a real opportunity. Many firms are formed on this premise and quickly fail because of seriously underestimating the effort and resources required and failing to target specific customers, etc. To avoid this type of failure, research and evaluation of ideas are necessary.

However, due to the wide differences in the types of opportunities, different types of customers, different types of products and industries involved, there is no standard method of opportunity evaluation that can be utilized. As each type of opportunity is unique in some way, different methods of evaluation are required. In established markets the more traditional methods of evaluating opportunities can be used, i.e., calculating total market size and competitors market shares, identifying and analyzing segments, etc. Through such straight forward analysis, one through focus groups and other forms of consumer research evaluate a product idea against the existing competitive products in the market. Risks can be assessed and appreciated, strategies created, resources assessed, and skills and capabilities assessed, etc.

A new to the world product, breakthrough technology, invention based new knowledge, a unique business model, or product/service bundle is another matter. Only the potential of the new concept in solving an existing consumer problem can be evaluated, and only in a very subjective manner. Products, services, and concepts that are based on a constructed opportunity are even more difficult to evaluate and are very unlikely to gain any serious airing from potential financiers. These concepts can only rely on an intuitive evaluation that may only satisfy the entrepreneur him or herself. Until these concepts are proved in the field, they are "fuzzy concepts" which after their success will appear perfectly logical in hindsight. (6) The risk of trying to evaluate some products, services, or concepts by traditional means will just raise too many "red flags" and reasons why the idea should not be preceded with, killing the idea completely. Sometimes entrepreneurs need the courage to act upon their own intuitions, rather than be influenced by others who will put negatives in the way about why it won't work. The skills and acumen needed to evaluate and make a decision upon any idea must be very flexible and mostly based upon intuition (7) to answer the following types of questions: Do I have customers? Will they support me? Do I have the skills and expertise required? How long will it take until I'm in a profitable situation? Is this viable? Am I committed? (Am I motivated enough?) What are the opportunity costs? What are the risks? Can I handle them?

Finally in the idea evaluation stage networking skills are needed to communicate ideas and seek feedback from peers and people involved within the field the idea have relevance. There is a large range in networking skills ranging from those people who have strong interpersonal skills and relevant contacts within the field, to those who find it difficult to communicate with others and/or have poor contacts within the relevant field. These skills are also important in the gathering of resources, open potential channels of distribution, create new customers, and communicate with other potential stakeholders, etc.

The start-up phase of an enterprise requires mainly functional or technical skills in three main areas; 1.) Skills related to the setting up of the legal, resource, and logistical aspects of the firm, 2.) Skills related to developing a new product or service and developing the means to produce them on a commercial scale, and 3.) Skills required in the promotion and sales of the products/services produced by the firm.

Skills related to the setting up of the legal, resource, and logistical side of the business involve the set up of the formal aspects of the legal vehicle for the firm. The complexity of this varies from country to country where a formal business entity is required to be formed, registration made for tax purposes, and several licenses and/or permits may be required as well. This is where the first requirement for basic administrative skills is required. Resource gathering skills are required at this stage to facilitate the development and future growth of the firm. The way this would be undertaken very much depends upon the type of enterprise starting up. If it is a small entrepreneurial start-up firm, it may rely on its own internal funds, small personal loans, and finding small credit facilities where it can, i.e., family, friends, credit cards, superannuation, etc. Physical resources may be borrowed or purchased cheaply, i.e., second-hand equipment, etc. More resource endowed firms may set the enterprise up according to budgets they developed utilizing their own funds or from an arranged bank overdraft, if this has been successfully negotiated with a bank. However these activities will require the ability to develop a business plan and oral presentation skills. The setting up of early logistical aspects of the firm may only require the identification of transport carriers, potential suppliers, support services and other necessities for future operational activities.

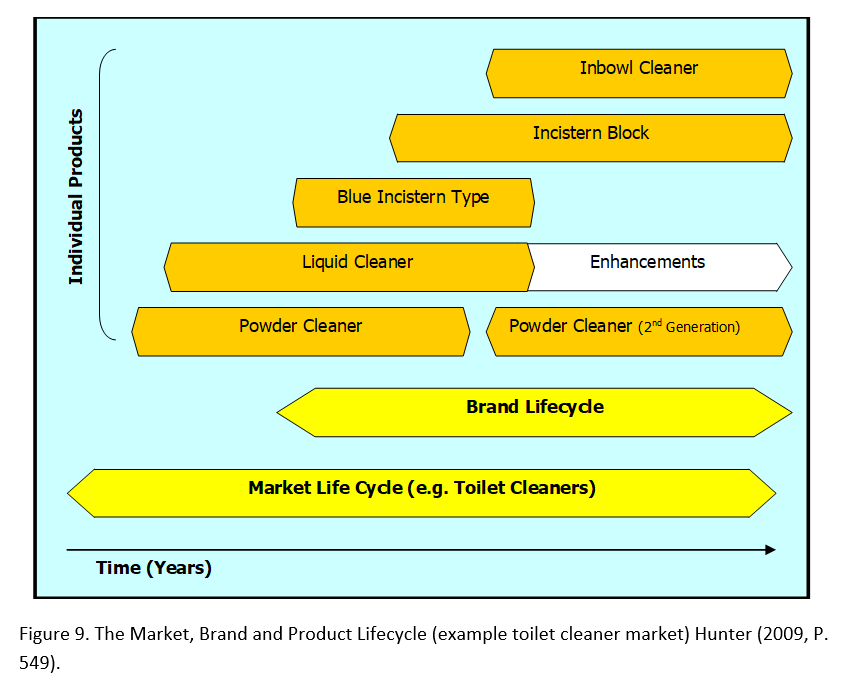

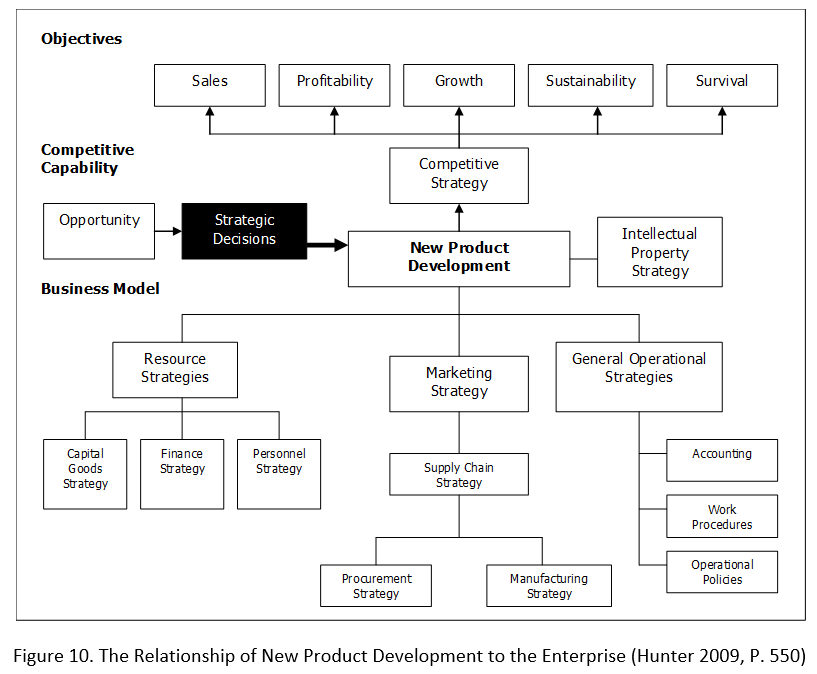

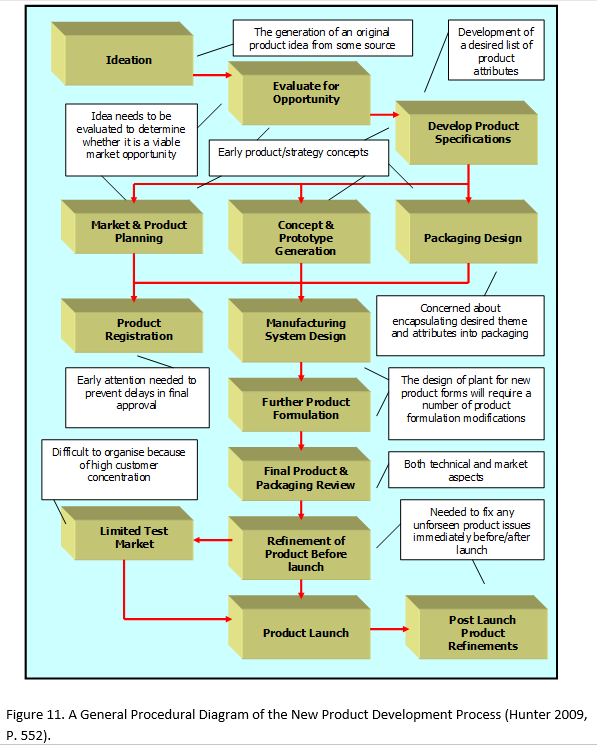

There are numerous skills required to develop a new product or service and developing the means to produce them on a commercial scale are primarily technical and functional. New product development is a very complex task and requires numerous technical and conceptual skills to satisfactorily undertake this task. The specific skills required in each type of product will depend upon the actual physical characteristics and what the production processes involve. If the product is highly technical, then it would be very likely the founders involved in the enterprise would have most of the product knowledge required to produce the product, and be able to obtain what knowledge they require fairly easily. Likewise the founders involved in FMCG products would also be expected to have a sound working knowledge of how products are constructed and their respective production processes. The founders of a firm providing a service still need to develop it like a product as it has attributes and a supply chain just like any product. Presumably they will know how to develop the infrastructure and support networks that the service requires to satisfy customer needs. New product development is a firm capability which will be discussed later in this chapter.

In most industries, the majority of time during the start-up phase will be devoted to sales and promotion. In the start up phase of an enterprise, sales and promotion will be the only reason for the firm's existence, and the only reason that the firm will continue to exist in the future. The success of the firm depends almost entirely on sales and promotion. Early sales that the enterprise achieves will dictate the momentum of firm growth. Too little growth will create a situation where revenues don't cover costs, which may inhibit the sustainability of the firm. Too fast a growth on the other hand will extend financial resources to the point that a firm may face cash flow deficiencies which will inhibit firm functioning. Skill is required to maintain sales growth within specific parameters that the firm can sustain without undergoing too much stress. To some degree the early sales path will influence the emotional disposition of the firm's founders and early employees greatly, especially in low resource based firms where founders are fully committed to their venture.

Highly skilled and experienced practitioners in some industries may be able to launch a product within a field incurring minimum promotional and selling costs. They will know how to spend promotional monies wisely and gain product prominence without spending large amounts of money that other firms in the field will find necessary to spend if they don't have the same experience. This advantage comes in part from a long exposure within the field with good relationships. Very experienced founders in some fields may be able to save up to 40% on the initial enterprise expenditure required, which gives a small start-up firm some advantages in the early period.

Most of the skills discussed above are still required in the early growth stages of the enterprise. The firm within the early years will most probably still be looking for new ideas that present viable opportunities. These ideas will be evaluated and decisions made on which way the enterprise will proceed in the future. This means the need to develop more new products/services and a further focus on sales and promotion. The founders will start to also focus on developing the formal organization, requiring organizational and management skills as revenues, cost and staff numbers increase.

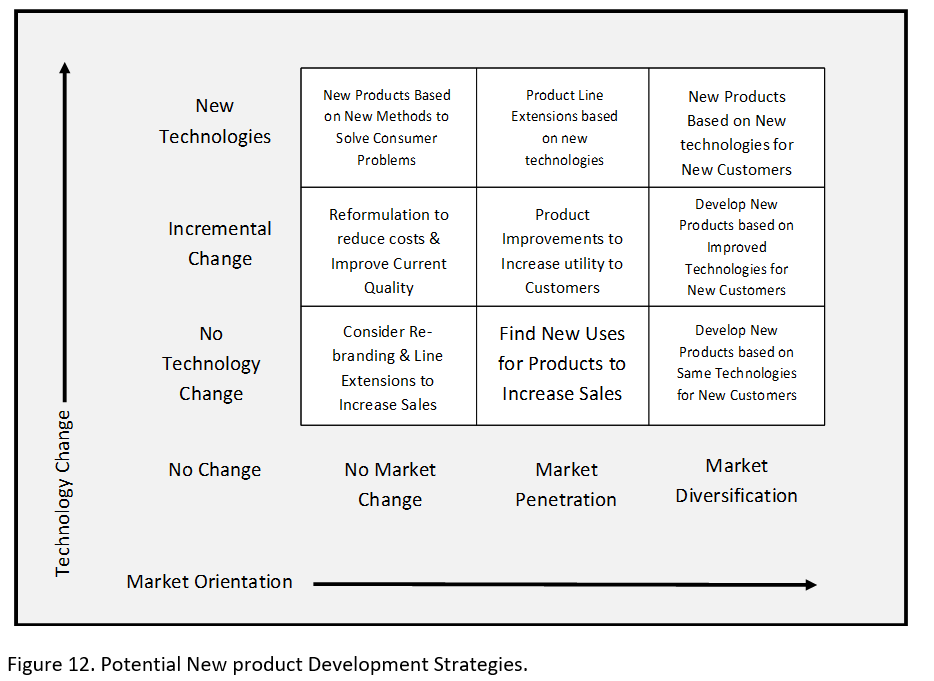

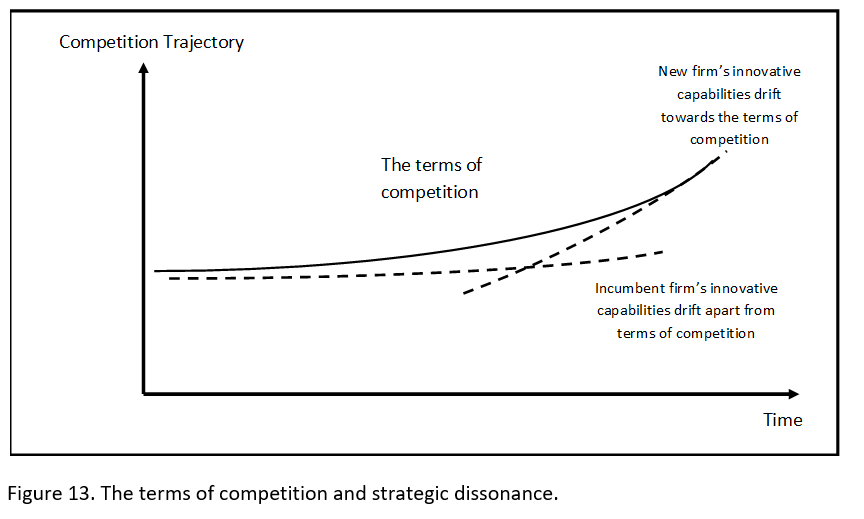

As a firm's growth slows down, it begins to make a transition from the growth to the maturity stage; the momentum of the organization begins to change. The firm's growth was based upon the unique position it defined for itself based upon a source of opportunity. After a period of time new firms enter the competitive field, competing on the same or similar premise. The paradigm of competition changes towards competition and on finding some form of incremental differentiation and/or market segmentation to create competitive advantage, rather than a unique advantage.

The firm slips into the form of a formal organization in need of managerial direction rather than entrepreneurial leadership. The firm must maintain a number of complex operations, i.e., sourcing, procurement, manufacturing, marketing, sales, finance, accounting, and administration, etc. Seeking growth through relatively risky ideas becomes secondary to managing what already exists. General management skills, accounting skills, finance skills, cash flow management skills, marketing skills, sales skills, human resource management skills, and manufacturing management skills become very important in the control and performance of the firm.

Michael Gerber (2001) argues that many small businesses were formed out of the love and desire to practice a technical skill that the founder enjoys, rather than the wish to become an entrepreneur. Through the stresses of running a business, the technician orientated founder is forced to become a manager and overcome the complexities of running a business. Some people are good technically, while others are good at starting new things, while others may be good at managing. Not many people are good at all three. People tend to be skilled in particular areas and take time an experience to develop skills in other areas. This should occur in a firm if the founder has the willingness and motivation to do so. Not all founders do.

Specific areas and problems require specific skills, and therefore different businesses will also require different skill sets. Conceptual and technical skills are important early on, while management and functional skills become more important later on during the enterprise's evolution. What is important that the skills a person has and develops go together to synergize into competencies which bring strategic intuition and wisdom.

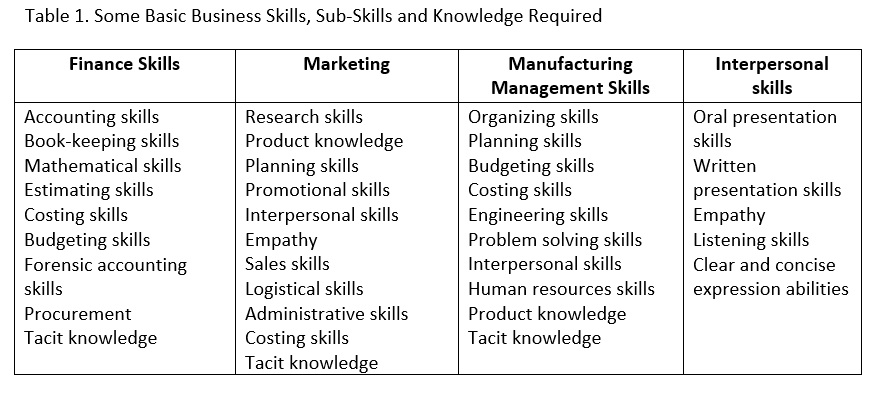

Before moving onto discussing personal competencies, it is important to mention that each of the basic skills discussed above are made up of sub-skills and parts of knowledge. For example accounting skills require book keeping skills, arithmetic skills, knowledge of the basic accounting rules and procedures. These sub-skills and parts of knowledge are important for mastering each basic skill. Some skills may also be skills in their own right but also a sub-skill of another skill, making up a web of skills and knowledge required to master any specific skill. For example finance skills, would require the sub-skills of accounting, cash flow management, budgeting, costing and estimating, etc. Many business issues are interdisciplinary where for example procurement systems are embedded within business accounting and financial systems and also related to product costing and manufacturing planning. Table 1 shows some basic business skills and the subskills that make them up.

Studies have shown that a perception of lack of knowledge and experience relevant to business can put people off the idea of going into business because of their self-perception of self efficacy (Gibb & Ritchie 1985, Robertson et al. 2003).

4. Personal Competencies

Personal competencies can be considered higher level characteristics encompassing personal traits, behavior, knowledge, and groups of skills. For example, swimming is a skill and synchronized swimming can be considered a competency. Competencies are much wider than skills, expertise, motivation, personal traits, self concept, knowledge, and acumen, as they combine to form a platform for future behavior. Personal competencies are also situational and socially defined. For example, the ability to find where schools of fish exist is a maybe a very important competency for an Eskimo in Alaska, but useless to a stockbroker in Wall St. New York. Personal competencies are the total ability of a person to perform a job or a task successfully (Man et al. 2002). They are a set of attributes that are relevant to the exercise of successful activities, in the case of entrepreneurship, the creation, growth and survival of a firm. Personal competencies have important implications for firm performance.

In early enterprise start-ups, personal competencies almost directly influence organizational performance. The basic role played by the owner/manager is one of the major determinants of SME competitiveness because the concentration of decision making power is in the hands of the owner/manager. Thus competencies become firm capabilities in the SME environment, which consequently influences the firm's overall strategy.

Personal competencies have been vaguely defined and often confused with skills, attributes, traits and capabilities (Hayton & McEvoy 2006). Terms like competencies, skills, knowledge, and expertise are often used interchangeably with insufficient consensus on the meanings. The boundaries of personal competencies are ill-defined and overlap, as many skills, knowledge, and other traits are not exclusive to any single competency.

One of the difficulties of defining personal competencies is that we have difficulties explaining what characteristics make a person successful, although we can see that they are successful. One can consider the CEOs of Goldman Sachs Lloyd Blankfein, Oracle--Larry Ellison, Xerox--Ursula Burns, John Paul DeJoria --John Paul Mitchell, OWN--Oprah Winfrey, Las Vegas Sands group--Sheldon Adelson, Starbucks--Howard Schultz, Cirque Du Soleil--Guy Laliberte, Chelsea FC and Oil Tycoon--Roman Abramovich, and Hutchison Whampoa Ltd.--Li Ka Shing. All commenced their lives in different forms of adversity and started their careers from the bottom. (8) Yet their individual successes are based on totally different factors, behavior, and mixes of competencies that enabled them to found (in some cases) and lead these successful corporations.

The characteristics of people are not the same, entrepreneurs and managers develop and transform their organizations and add value in their own unique ways of organizing resources and opportunities (Bird 1995).

Competencies are not uniform within the population. They probably exist within a "bell curve" distribution, so only a small percentage of the population possess the competencies necessary to spot opportunities, strategically evaluate them, engage in a start-up, and manage an organization (Lado & Wilson 1994). Competencies aren't easily transferred from one person to another. If competencies contain both functional and tacit knowledge, the functional aspects like marketing knowledge can be taught, but the tacit aspects are not teachable in the same way. Tacit competency knowledge involves creative, inductive, deductive and generative thinking processes which are more easily picked up by individuals who are naturally talented. Any teaching curriculum cannot develop competencies needed by an entrepreneur, but only serve to demonstrate the processes involved in being successful (Henry et al. 2005). Educators cannot create entrepreneurs anymore than they can provide foolproof, step by step methods that ensure success (Miller 1987). Self confidence, persistence, and high energy levels cannot be taught in the classroom (Miller 1987). We hope to develop competencies through education, but it is more likely we advertently pick up groups of skills that have not yet formed into competencies. These aspects of competencies can only be learnt through practice, experience and trial and error.

Personal competencies don't directly contribute to firm competitive advantage. Being competitive and operationally effective requires different disciplines (Waheeduzzaman & Ryans 1996). Competitiveness is related to strategy which deals with external factors, while competencies enhance internal organizational capabilities, which form the anchors of strategies. Therefore competencies facilitate capabilities. The level of operational effectiveness that individuals assist in creating will depend upon the freedom within the organization for individuals to be allowed to excel and work together for the organization's benefit. (9)

Different frameworks and competencies have been suggested by various authors. Boyatzis (1982) suggested that all competencies should have three major elements; 1. They should contain motives and traits, 2. There is a social role and aspect of self concept, and 3. Competencies enable role transactions. Competencies thus have a functional and tacit aspect which enables behavior. For example a management competency is made up of various pieces of management knowledge but rely on personal skills to act upon the knowledge. Some of the major types of personal competencies that have been described in the literature are summarized below.

Opportunity Competencies are related to recognizing and developing market opportunities by various means and methods (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1997, Chandler & Jansen 1992, McClelland 1987, Mitton 1989, Snell & Lau 1994). Opportunity competencies are about alertness, i.e., the ability to see unexploited opportunities (Kirzner 1973, 1979) and having the ability to see the environment through different perceptions (Casson 1982). An entrepreneur must have the ability to interpret environmental conditions and distinguish between the subjective and objective environments (Westerberg et al. 1997). (10) Opportunity competencies are closely related to relationship and conceptual competencies in developing the competitive scope of SMEs (Man et al. 2002).

Relationship Competencies are related to interpersonal interactions and relationships. They are concerned with building trust, empathy, cooperation, building teamwork, communications, networking, persuasive abilities, and other interpersonal skills (Bartlett & Goshal 1997, Bird 1995, Chandler & Jansen 1992, Durkan et al. 1993, Lau et al. 1999, McClelland 1987, Mitton 1989). It is through relationship competencies that entrepreneurs and managers utilize their other competencies. Relationship competencies are closely related to organizational competencies as it is through relationships that things get done.

Conceptual Competencies are related to a person's conceptual abilities. Conceptual competencies are reflected in understanding problems, problem solving, decision making, seeing things holistically, and conceptualizing things ideas and concepts (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1997, Bird 1995, Chandler & Jansen 1992, Durkan et al. 1993, Lau et al. 1999, McClelland 1989, Mitton 1989, Snell and Lau 1994). Conceptual competencies are important in innovating new ideas, new processes, new products and new services (Man et al. 2002). Conceptual competencies are closely related to opportunity, entrepreneurial, managerial, leadership, and organizational competencies.

Creativity Competencies are related to constructing opportunities, crafting strategy, and solving problems. Creativity involves the traits discussed in chapter four of volume one which include a motivational trigger, creative sensitivity, focus and attention, attenuation, imagination, curiosity, prior knowledge, emotion affect, and ego to create the right conditions. Creativity also requires knowledge and mastery of a number of creativity tools (or ways of thinking) to exercise creativity and gain new insights into the environment, opportunities, or in solving problems. The distribution of creativity is not uniform throughout the population (Simonton 2003). Creativity competencies are closely related to emotional intelligence, opportunity, entrepreneurial, strategic, management, and conceptual competencies.

Entrepreneurial competencies are related to the exercise of successful entrepreneurship. Some believe that entrepreneurial competencies are invaluable for start-up and enterprise development activities (Man et al. 2002). Entrepreneurial competencies involve resource gathering, self confidence, persistence, sense of achievement, decisiveness, optimism, networking, opportunity evaluation, strategy crafting, intuitive decision making, development of products and services, idea generation, negotiation skills, environmental scanning, and opportunity exploitation abilities. Entrepreneurial competencies are the total ability of the entrepreneur to perform a job role successfully and are extremely important in the start-up and early growth phases of the enterprise.

Management Competencies can be used interchangeably with the term Organizational Competencies which are related to the organizing of internal and external physical, financial, human, and technological resources of an organization. They involve teambuilding, leading, mentoring, training, allocating, and controlling employees (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1997, Bird 1995, Chandler & Jansen 1992, Durkan et al. 1993, Lau et al. 1999, McClelland 1989, Mitton 1989, Snell and Lau 1994). Other management attributes that are important to managerial competencies include, the ability to develop management systems necessary for long term functioning of the enterprise, resource acquisition skills, operational skills, managerial experience, coordination skills, communication skills, familiarity with the market, financial and budgetary skills, management style, and technical skills, etc. Management or organizational competencies involve transforming resources into higher value products and services (Grant 1991), i.e., using inputs effectively and efficiently, and the delivery of value to organizational stakeholders. Management or organizational competencies assist the entrepreneur enact a beneficial firm-environment relationship (Hambrick & Mason 1984, Tushman & Romanelli 1985). Management or organizational competencies are closely related to relationship, conceptual, managerial, and entrepreneurial competencies, and contribute to organizational efficiency and effectiveness.

Strategic Competencies are related to setting, evaluating, and implementing strategies of the enterprise (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1997, Bird 1995, Chandler & Jansen 1992, Durkan et al. 1993, Lau et al. 1999, McClelland 1989, Mitton 1989, Snell and Lau 1994). Strategic competencies provide a cognitive map (Weick 1979) that supplies the underlying logic for combining, deploying, and mobilizing resources within the firm and among the various organizational business units (if a large organization) (Prahalad & Bettis 1986). Strategic competencies are important in ensuring the long term performance and survival of the firm, verses the short term. Therefore people that possess strategic competencies will tend to consider the medium and long term implications of the decisions they make. Strategic competencies add a vision dimension rather than allow the making of decisions through impulse. There appears to be a positive relationship between planning and performance (Davig 1986, Ibrahim 1991, Kargar 1996), even if planning is informally undertaken is most entrepreneurial and SME firms. Informal planning has the function of forcing the entrepreneur to think towards focused objectives. Not only is goal setting and motivation required in the early stages of a firm, but this should continue into the growth and mature periods of the enterprise's lifecycle (Kuratko et al. 1997), which strategic competencies tend to support.

Leadership competencies are related to the ability of the entrepreneur or manager to articulate a strategic vision, communicate the vision throughout the organization, and empower employees about the vision (Westley & Mintzberg 1989). Some leadership traits include the ability to motivate and lead staff, building trust, conflict resolution, creating shared visions, developing teamwork, and mentoring. The leadership competency is closely related to the management, entrepreneurial, and strategic competencies and is important to firm performance.

Commitment Competencies drive the entrepreneur to commence and remain committed to the business (Bartlett & Ghoshall 1997, Bird 1995, Chandler & Jansen 1992, Durkan et al. 1993, Lau et al. 1999, McClelland 1989, Mitton 1989). The entrepreneur needs to maintain internal focus on organizational activities, whilst also maintaining a critical external focus on the larger business environment (Adam & Chell 1993). Commitment competencies also incorporate ambition, aspirations, desire, and long term motivational factors that drive the entrepreneur to meet his or her objectives. While commitment competencies can have a very positive effect, they also can have a negative effect. Commitment competencies can distort objectivity concerning firm performance and thus prevent a person coming to a decision that it is no longer viable to support a firm that is continuing to perform poorly over a long period of time where exit may be the best option. Commitment competencies are strongly related to strategic competencies as a factor contributing to long term performance.

Ethical Competencies can be considered the possession of appropriate personal and professional values and the ability to make social judgments based upon a work related situation (Cheetham & Chivers 2005). Ethical competencies bring an ethical frame into the decision making process domain of an individual. Ethics usually come from history, the law, a society's cultural values, personal moral codes, religion, various institutions, other social codes, and sensitivity to the needs of others. Ethics are not synonymous with knowledge as ethics require interpretation in order to apply rules and codes to real life situations. Individuals are usually left with discretion in developing and applying concepts. Ethical competencies tend to be integrated with opportunity, conceptual, entrepreneurial, managerial, and leadership competencies.

It could be argued that Emotional Intelligence (Competencies) is a personal competence required in entrepreneurship and developing an enterprise due to the need of emotional maturity, objectivity, and stability required. Some important aspects of emotional intelligence are the ability to recognize and manage one's own and others emotions, to motivate oneself, to be able to restrain impulses, and to handle interpersonal relationships effectively. According to Daniel Goleman (1998), emotional intelligence is a learned capability that results in outstanding performance in working situations and determines our potential to learn, based on our self awareness, motivation, empathy, self-regulation and adeptness to relation ships. Some of the important traits related to emotional intelligence include emotional awareness, self assessment, self worth, self control, adaptability, commitment, initiative, optimism, ability to manage conflicts, leadership, ability to influence others, and team capabilities.

Personal competencies are the building blocks upon which organizational capabilities, and in turn, organizational strategies are built upon. How effective this is depends upon how freely employees are able to exercise their personal competencies and how well respective employees' competencies are synergized within the organization. This is not so important in an entrepreneurial start-up where the competencies of the founder will usually dominate, but very important in a firm with many employees. While the entrepreneur's experience, education, and training are important to the possession of personal competencies, there is little conclusive evidence that strong competencies are reflected in age (Cooper & Gascon 1992).

An individual is as effective or limited in functioning effectively at specified tasks according to the limits that their personal competencies allow. There are numerous personal competencies and great overlap between them. Personal competencies tend to form an overlapping lattice where competencies are balanced and mutually support each other. When this occurs, a person will be able to work very effectively and perform at their best. There mere procession of competencies does not make a person necessarily competent. It is a person's view and perception of the environment that triggers the use of personal competencies, so competency activation is reliant upon external stimuli and motivation.

To develop our personal competencies, one must develop what Peter Senge (2006) calls "personal mastery." Personal mastery is concerned with personal growth and development so that real learning can take place. Personal mastery involves using our skills and competencies at the highest possible level where we achieve creative fulfillment and spiritual growth (Senge 2006, P. 131). Personal mastery enables a person to see things more objectively without biases and other cognitive blocks. A person with personal mastery has vision and the desire to be creative. He or she remains curious and inquisitive about why things occur the way they occur. People with personal mastery are aware of their strengths and weaknesses and their ability to achieve. They are on a continual quest to learn and improve. Personal mastery also brings true courage and commitment to pursue the personal objectives a person may have.

To develop personal mastery, one must work on a series of "principals and practices" according to Senge (2006, 136). These principles and practices are:

* One must develop a sense of vision, 'a big picture' of what they want out of life. This goes much further than goals and objectives that don't carry the same deep meanings about life that a vision contains. Visions are intrinsic that gives one a sense of purpose, motivating action and persistence.

* One must create tension inside to generate energy to pursue the vision from where they are today (This was discussed under the section Motivational Trigger in chapter three of volume one).

* We must overcome our own deep feelings of powerlessness and recognize our own coping and defence mechanisms (See Emotional Attachment, Defence Mechanisms and Neurotic States in chapter three of volume one),

* We must see our true selves and our respective dysfunctional behaviours, and

* To master a large repertoire of skills so that they can be carried out almost subconsciously, i.e., the task is integrated with the self.

People with personal mastery are able to integrate intuition and reason which is where personal competencies can be utilized very effectively. Competencies are thus multidimensional constructs (Smith & Morse 2005). They are deeply rooted in a person's background, being acquired through education, training, and experience (Man & Lau 2005).

Competencies play differing roles and importance during the various stages of the firm lifecycle. It is the understanding of the importance of these different roles that can be crucial to successful business growth (Churchill & Lewis 1983). The type of competencies that are needed in the start-up i.e., entrepreneurial competencies will differ from the types of competencies that are needed during growth period, i.e., managerial competencies. As each enterprise varies in the type of opportunity it is attempting to exploit, the entrepreneur has to acquire unique resources and skill combinations to enable the venture to progress successfully (Mitchelmore & Rowley 2010). Likewise, the range of skills and competencies required to run a small business are qualitatively and quantitatively different from those needed to run a large business. New venture founders often find it very difficult to move from the start-up phase, relying mainly upon entrepreneurial competencies to the maturity stage, requiring mainly management competencies (Galbraith 1982). An adequate level of management skills and training is essential to the transformation of a firm from an entrepreneurial organization to a profoundly management organization (Hofer & Charan 1984).

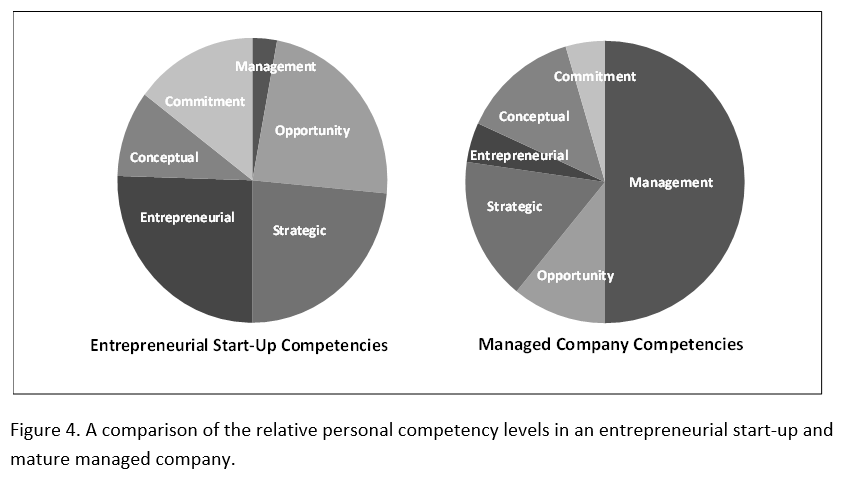

Figure 4 shows two pie charts indicating the relative amounts of personal competencies required to undertake an entrepreneurial start-up and manage a mature company. This is metaphorical as personal competencies truly blend together and overlap through their common skills. Also, the proportion of each personal competency will vary according to individual, as each person will have different strengths and weaknesses. Other influences on the proportion of personal competencies within each enterprise situation include the particular challenges facing a person, the type of business, personal business orientations and styles, and the different sets of skills individuals have.

When a firm moves from an entrepreneurial to a managed business, or a professionally managed business, this is where it is possible to recognize a change from reliance on individual level competencies to firm level capabilities. Competencies are to an individual, as capabilities are to an enterprise.

5. Enterprise Capabilities

Over the last few decades enterprise capabilities have been referred to as distinctive competencies (Selznick 1957, Snow & Hrebiniak 1980, Hitt & Ireland 1985, Reed & DeFillippi 1990, Fiol 1991), resource deployments (Hofer & Schendel 1978), invisible tenets (Itami & Roehl 1987), organizational capital (Prescott & Visscher 1980, Ranson 1987, Tomer 1987), core competencies (Hayes et al. 1988, Prahalad & Hamel 1990), organizational capabilities (Ulrich & Lake 1990, Stalk et al. 1992), and firm specific competencies (Pavitt 1991). These various names reflect differing perspectives concerning enterprise capabilities. Most of these perspectives share the view that the foundation and shape of long-term strategy rests upon a firm's internal resources and capabilities (Grant 1991, Lado & Wilson 1994).

Enterprise capabilities can be seen as sets of skills, competencies, organized routines, and knowledge that utilize complementary assets to perform and coordinate a set of tasks that are consistent with the firm's strategy at the time. This implies that enterprise capabilities coordinate both at the individual and organizational level to achieve higher level routines that assist in management decision making, operating and coordinating work flows with the view of achieving specific objectives (Winter 2000). These routines are learned and include manufacturing, marketing, procurement, new product development, and general management, etc. (Nelson & Winter 1982).

Enterprise capabilities provide the internal firm dynamics needed to pursue company growth and competitiveness (Chandler 1990). They are strategic assets which enable a firm to adapt, compete, and survive within dynamic environments (Teece & Pisano 1994). Enterprise capabilities are heterogeneous and unevenly distributed and deployed across companies within a given competitive field. It is the differences in enterprise capabilities which partly accounts for the different competitive positions of firms and their individual performances (Conner 1991, Rumelt 1984). For example Wal-Mart's logistical capacity could be seen as being superior to its domestic US competitors and Toyota's performance on a number of levels has been superior to that of General Motors and Ford. One will find within single industries that some companies are much more profitable than others, signaling the importance of firm specific factors like enterprise capabilities may play some important role (Rumelt 1991, Jacobsen 1988, Hansen & Wernerfelt 1989). Each enterprise capability a firm possesses is drawn from its internal skills, knowledge, systems, routines, efforts, and historical experiences, and therefore to some extent, unique to that firm. Enterprise capabilities in the right areas, truly distinctive ones, i.e., for example logistics for Wal-Mart and quality for Toyota, can provide a real key to a company's success and future development (Learned et al. 1969).

The major objective of enterprise capabilities is to anchor strategy and create firm effectiveness in terms of cost, customer service, logistical mastery, sales, technical service, manufacturing, organization, and new product development, etc. This enables a company to compete and pursue its objectives. Therefore in terms of opportunity, the important question is: "Does the organization have the capabilities to exploit a particular opportunity?" Broken down into specific functional areas the question is: "Does the organization have the capabilities to execute specific jobs that are needed to be completed in order to exploit an opportunity?"

Enterprise capabilities are the means through which things get done. These capabilities reside inertly within the methods and processes by which people in the organization transform inputs of labor, energy, raw materials, information, and technology into higher value outputs and within the organization beliefs and values managers and employees utilize when making decisions (Leonard-Barton 1992). Consequently it is very difficult for competing firms to directly emulate many enterprise capabilities of other firms directly, as any capability contains many intangible attributes. Enterprise capabilities cannot be measured and itemized on balance sheets or organizational charts, yet they positively exist (Teece et al. 1997).

The firm's success in the environment is a result of the effectiveness of crafted strategies within the environment. However any strategy is only as good as what it is premised upon and what anchors it. Thus the success of any enterprise depends upon many factors, not neglecting the ability of managers to maintain a viable balance of (strategy) supporting capabilities (Thompson 1967, Schendel & Hatten 1972). This is the basis of resource based theory where Penrose (1959) argued that a firm creates a strong base by specializing in physical resources, including tangible assets like raw materials, plant and equipment, etc., and human resources including intangible assets like financial, managerial, technical knowledge or skills. A firm explores and experiments with all the resources it has at hand to create new value added products or services in the exploitation of markets that add growth to the enterprise, rather than collecting unrelated resources. These resulting capabilities are the result of years of accumulated decisions and actions taken in uncertainty (Henderson 1994).

Enterprise capabilities are thus effectively developed through years of work and experience (Cohen & Levinthal 1990), historical condition (Barney 1991), and through socially complex interactions (Amit & Schoemaker 1993, Reed & DeFillippi 1990). Consequently enterprise capabilities can become rigid. For example, organizational culture (Barney 1986), Organizational routines (Nelson & Winter 1982), and the firm's reputation and image (Weigelt & Camerer 1988) cannot be transferred very easily to other organizations. Enterprise capabilities become unique to the firm. However although these capabilities may be diverse, they are set in, rigid, but intangible. As a result a firm may not be able to diversify its capabilities due to this rigidity and miss out on future opportunities (Leonard-Barton 1992), or may be able to grow incrementally along the path set by the cluster of capabilities through slow expansion and diversification (Davies & Brady 2000).

Each firm will have a number of enterprise capabilities which will differ in number, types, and quality from enterprise to enterprise. Each enterprise capability contains embedded knowledge, skills, values and norms. These characteristics with their embedded tacit knowledge affect the firm's ability to undertake strategic and functional tasks, to create more knowledge resulting in new products and services, make both strategic and managerial decisions. Enterprise capabilities also define value and influence of particular knowledge structures within an organization. They decide individual verses collective decision making, centralized verses decentralized decision making, who controls information flows, and the degree of autonomy verses control. Enterprise capabilities also carry political values, where the weight of marketing over production, finance over procurement, and divisional management over line management is decided within the nature of enterprise capabilities. Enterprise capabilities are institutionalized (Zucker 1977) and become a firm's taken for granted realities, within the fabric of the firm's corporate culture (Schein 1986). Enterprise capabilities also dictate the degree of creativity the members of a firm can express depending on the types, combinations and rigidity of these institutionalized routines. Some of the major enterprise capabilities are summarized below.

6. Management Capabilities

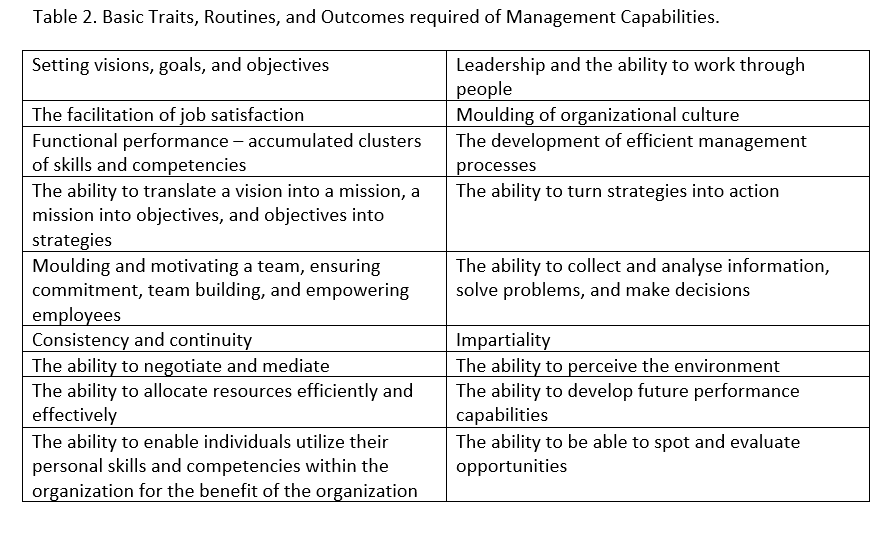

Management knowledge is a pivotal firm resource and plays an important role in firm performance (Fayol 1948, Mintzberg 1973, 1994), although this relationship with performance has not been explored thoroughly in management literature (Bartlett & Ghoshal 1993). Management plays a key role in delivering business performance and logically better management capabilities should engender higher management performance. Management capabilities comprise of are accumulated explicit and tacit knowledge that is utilized to fulfill a large number of tasks and requirements needed in driving and operating an organization through the different levels of management. (11) Basic traits, routines, and outcomes required of management capabilities are listed in Table 2 below. There are great differences in the types and composition of management capabilities between organizations (Clark & Fujimoto 1991).

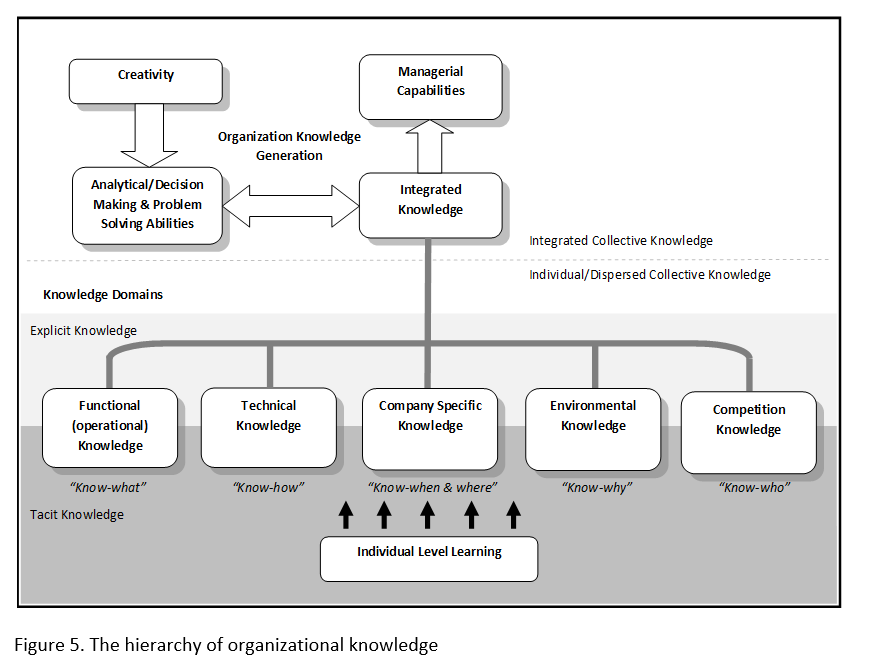

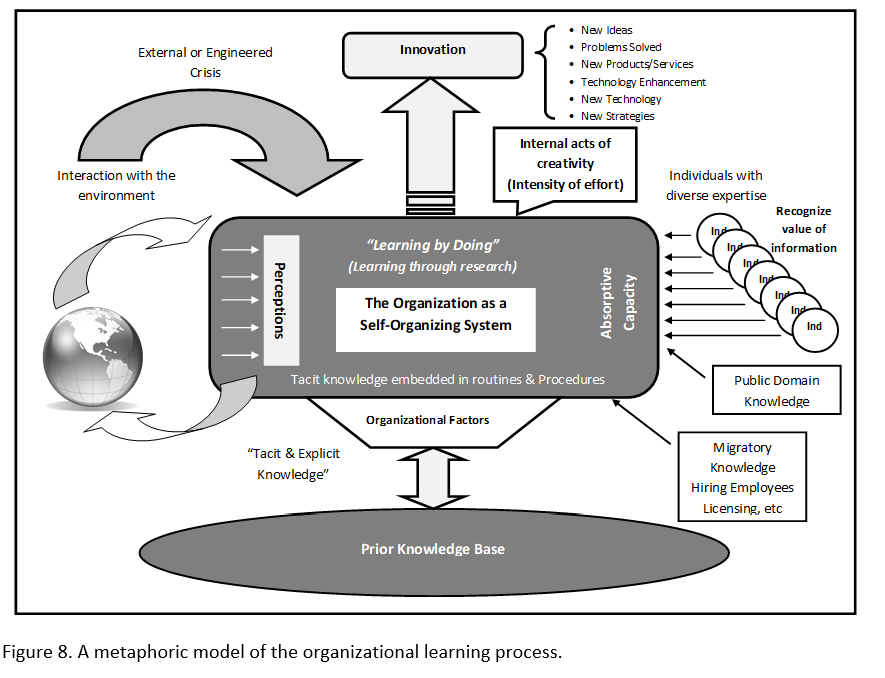

To understand the performance of firms, great attention should be paid to the knowledge the enterprise has access to, and to the knowledge creation process itself. As knowledge supports the basis of managerial capabilities, this creates barriers to competitors who try to imitate the firm, which infers knowledge is a strategically significant resource of the enterprise (Grant 1996). Continual knowledge creation is imperative in a dynamic environment as the firm needs to adapt to changing environmental conditions and evolving competition (Nonaka & Takeuchi 1995). This includes both explicit and tacit knowledge creation, which occurs at the organizational level through analysis, problem solving, and decision making, utilizing various levels of creativity, as enterprise capabilities are essentially organizational (Kogut & Zander 1992, Teece et al. 1997). However enterprise capabilities also rely upon individual knowledge absorption, as knowledge occurs both at the individual and organizational level (Spender 1996).

Integrated knowledge at the organizational level is primarily related to how assets, resources, and capabilities are deployed to pursue strategy for the firm (Grant 1996). Within this integrated knowledge is a combination of higher order knowledge in regards to how to undertake the functions of organization. The various knowledge domains produce mental models both on an individual level and on an organizational level. These domains encapsulate experience, knowledge, intelligence, skills and competencies related to each respective area.

The functional (operational) knowledge domain includes all knowledge about general management, human resources, logistics, marketing, manufacturing, and finance capabilities, etc. (12) Functional knowledge can be broken down into specific technical knowledge domains. An example of a firm with outstanding functional qualities is McDonalds which produces exceptionally consistent products, human resources training and management, market research and localized product development, financial control and operations management that enable it to operate thousands of restaurants with remarkable consistency throughout the world.

Katz (1955) defines technical knowledge as an understanding and proficiency in specific kinds of activities involving methods, processes, procedures, and techniques. This includes both general knowledge and specific company skill knowledge (Castanias & Helfat 1991). Black and Decker's designing of tools utilizing small electric motors or Canon's ability to integrate optical, microelectronic, and precision mechanical technologies together in their cameras are examples of outstanding use of technical capabilities. These functional and technical capabilities will generally be held by the junior and middle managers within the firm.

Company specific knowledge would include specific conceptual skills that assist in the ability to see the enterprise as a whole and conduct what is specifically necessary for the firm to function. Company specific knowledge grasps and integrates technical, human, processing, and conceptual knowledge together. Company specific knowledge also entails what the firm stands for (Simon 1985). Air Asia's ability to provide an efficient service that is on time, convenient, and safe, with a young enthusiastic team is an example of company specific capabilities.

Environmental knowledge relates to industry specific knowledge that enables the firm to operate within the environment. Banks know how to operate in the financial environment, as do airlines understand how to operate within the aviation environment. Competition knowledge specifically relates to operating within the competitive field the firm is directly engaged within. Sara Lee, Kraft, Cadbury, and Pfizer all understand how to compete exceptionally within their respective competitive fields.

Some managers will specialize in particular areas, but the combined knowledge is integrated to form management knowledge. These aspects of knowledge share a tacitly shared accumulated experience (Tsoukas 1996), which socializes, externalizes and internalizes, sets governing principals, which is codified for specific firm operation, integrates the organization (Boisot 1995) and forms routines (Nelson & Winter 1982). Again, they exist both explicitly and implicitly (Tsoukas 1996).

The combination of all this knowledge at the integrated organizational level is something like "management cognition," guided by management processes forming a strategic logic (Sanchez & Heene 1996). This integrated knowledge is different to the individual knowledge of respective individuals (Sanchez 1997), who will have their own mental model (Mahoney 1995) as well as shared enterprise mental models. How static or dynamic is knowledge accumulation depends upon how flexible management is in regards to contingencies posed by the changing environment and how creative management is in analyzing data, making decisions, and solving problems through reintegrating and reconfiguring their knowledge to create new combinations of knowledge.

Wisdom in any domain is concerned with understanding it as a system. Management must know what, how, when, where, why and who in order to apply knowledge through solving problems and making decisions, thereby creating more knowledge. Know-how, know-why, and know-what are related to firm processes, purpose, and current state of existence (Sanchez 1997). Know-how is concerned about how the different elements within a domain and the organization are interrelated. Know-why is concerned about why different parts of the system are interrelated. Know-what is concerned about what causes of action are available to the firm. Know-where is concerned about where the important and critical issues are located within the firm. Know-when is related to the time dimension of management and strategy (Van den Bosch & de Man 1997). Know-who is related to working through other people (Koontz 1964) and who controls or possesses certain parts of the system and has the power to make decisions. Wisdom is related to the ability of the knowledge system to become a "self organizing system" where solutions and new insights through manipulating knowledge patterns occur through management analysis, problem solving, and decision making. This creates new knowledge which enables the creation of new products and services, routines, perceptions, system rectifications, and new strategies. The hierarchy of organizational knowledge is shown in Figure 5.

However one of the risks with ingrained management capabilities is complacency, with a high regard for a firm's own management capabilities where organizations fall victim in a belief of their own infallibility due to past successes in the marketplace. Strategies can reflect hopes for the future and wishful thinking rather than wise contemplation. Many companies did not see the threats posed by new competitors entering the market as the US automobile makers ignored Toyota and Honda's entry into the US market and Harley-Davidson and BSA-Triumph did not believe Honda could seriously challenge their market leadership in the market for "up-market" motorcycles.

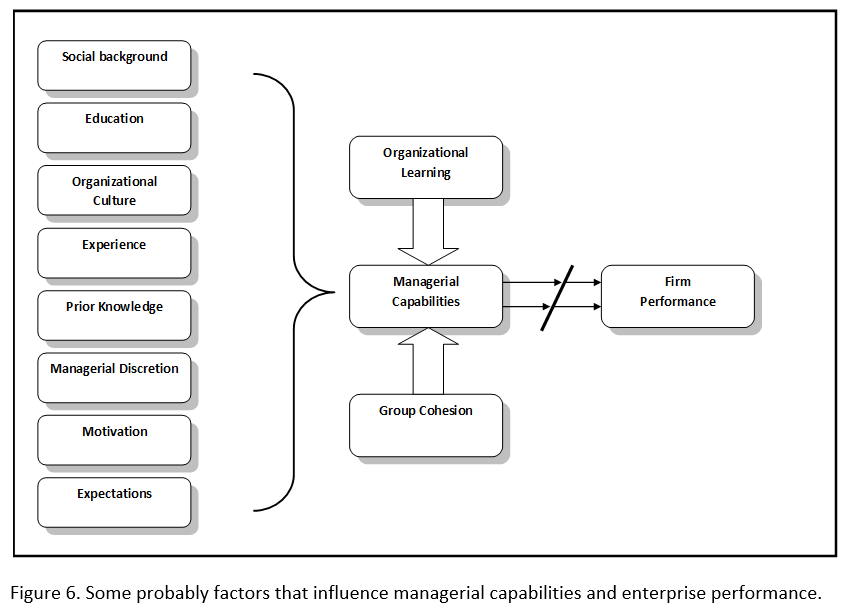

As mentioned in the introduction to this section, there is a relationship between management capabilities and enterprise performance, although we are not sure to what extent. The effectiveness of managerial capabilities is contributed to by a number of possible factors, which we also cannot quantify their influence. Firstly, managerial capability effectiveness is dependent upon the integration and cohesion of the members of the firm. Strong group cohesion should lead to shared perceptions, knowledge, values, and sense of importance in a collective setting, where managers are able to complement each other (Penrose 1959, pp. 46, 52). Poor group cohesion for whatever reason may lead to dysfunctional management capabilities.

Then come a set of background factors which may have varying influence upon management capabilities (which have all been discussed before), including social background, education, experience, prior knowledge, and motivation. These interactions are so complex that it may be too difficult to individually determine the influence of any individual factor upon management capabilities. Expectations are very important as they set a benchmark upon what performance is measured and what is expected. Management discretion or autonomy provides managers with the freedom and opportunities to use and develop their own judgment. The influence of organizational culture and learning will be discussed in their own sections. The broken arrows between managerial capabilities and enterprise performance indicate that the correlation of this relationship is unknown. This is schematically shown in Figure 6 below.

7. Entrepreneurial Capabilities

Firms mostly start with an idea and in their infancy are small, flexible, and adaptive to the nature of the chosen opportunity. The fact that a small start-up firm can make decisions fast, do things quickly and on the cheap, enter small market segments without direct competition, and modify products and strategy easily where needed, are the very traits that make a small entrepreneurial firm successful. Ideas can be gestated into products reasonably quickly, giving the small entrepreneurial firm many advantages over larger and mature incumbents.

Large firms can become cumbersome, lethargic, and complacent, making them slower to react because of high fixed cost to serve smaller market segments and find difficulty in modifying strategies due to their sunken investments. They lose the entrepreneurial drive that first made them successful and become very formal and management orientated. Many mature firms act as though they exist within a stable environment, only undertake revisions of strategy on a periodic basis and rely on natural growth of the market for their development, rather than making any innovations.

The capability to maintain a state of adaptation to the environment requires more than just management capabilities. Entrepreneurial capabilities are concerned with maintaining alertness to opportunities, evaluating them, and making decisions to exploit them. Entrepreneurial capabilities encompass more than gaining access to the necessary resources to make things happen, steering growth and surviving. Entrepreneurial capabilities are about actively searching for an applying new technology (13) to fulfill continuing visions of what the management of the firm envisages for the future. Entrepreneurial capabilities are about finding growth through rearranging resources, building new capabilities, employing new technologies in the pursuit of new visions. (14) Entrepreneurial capabilities are about maintaining alignment with the changing environment through making conscious strategic choices (Child 1972). Change does not just occur in the environment while a firm passively looks on. A firm's strategic interventions also change the environment (Wernerfelt 1984).

During early firm infancy, the founder may rely on his or her skills and personal competencies to get through. These evolve through the growth of the firm into first entrepreneurial capabilities and then into other enterprise capabilities. Entrepreneurial capabilities are built up upon early entrepreneurial initiatives (Garret & Covin 2007). Entrepreneurial initiatives build up new knowledge that develops other enterprise capabilities (Zahra et al. 1999). The development of other enterprise capabilities is an evolutionary process, usually entailing trial and error and experimentation (Zahra & Filatotchev 2004, Zahra & George 2002). A continued entrepreneurial capability throughout the life of the firm can facilitate the identification and pursuit of new entrepreneurial initiatives, thus maintaining alignment of resources, capabilities and opportunities. Entrepreneurial capabilities provide flexibility where mature firms can quickly deviate from set strategic paths. Entrepreneurial capabilities assist in providing flexibility (Birch 1987), innovation (Backman 1983), and growth (Drucker 1985).

Entrepreneurial capabilities facilitate two types of entrepreneurial initiatives, those that are intended and those that are emergent on an ad hoc basis. Intended entrepreneurial initiatives are activities that are the result of planned and purposeful action based on a strategy. This may include opening of a new outlet, a branch, the development of a new product or service, etc. They are intended to return a purposeful revenue and profit based upon the perceived opportunity and crafted strategy intended to exploit it (Lovas & Ghoshal 2000). Emergent entrepreneurial activities just happen without any formal recognition of any specific opportunity. They are an extension, or flexible move following a perceived opportunity path that is emerging of perceived within the environment. These initiatives occur serendipitously but usually linked to the current competitive field and technologies of the firm. These initiatives often occur where the founder or management cannot properly assess the scope of the opportunity and are very common occurrence at SME level.

The existence of entrepreneurial capabilities within a firm is dependent upon the attitude of individuals within the firm (Stevensen & Jarillo 1990). It is not just the founder/manager's attitude but also the rest of the employees as well. In addition opportunities cannot be pursued and exploited if they are not spotted and identified in the first place. Alertness to the environment is an important aspect of entrepreneurial capabilities and depends upon individual abilities, product, market, and technical knowledge. Entrepreneurial capabilities assist a firm develop strategic growth rather than rely upon natural market grow for its internal growth. This is a fairly rare capability (Leibenstein 1987) and is somehow connected to the values of the enterprise founders (Schein 1983).

Entrepreneurial capabilities are a driver of a firm's ability to renew itself (Stopford & Baden-Fuller 1990, Sambrook & Roberts 2005). Entrepreneurial capabilities are the sustaining characteristic of a firm that enables it to react to a changing environment. Without this characteristic a firm will be stifled, unable and unwilling to transform its products, processes, and strategies. Entrepreneurial capabilities enable a firm to keep stretching itself into new areas of opportunity and growth during its lifetime.

8. Organizational Culture

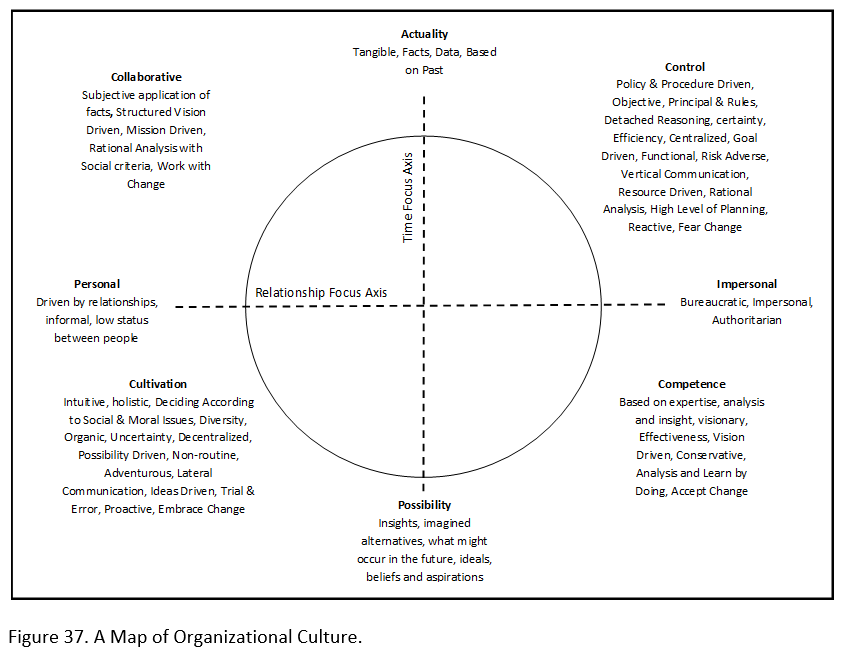

Organizational culture became very popular in management literature during the 1980s. However, most literature took a positivist approach which treated the various aspects of culture as objects that can be manipulated to achieve better organizational performance. The instrumentalist concepts of a power culture (Deal & Kennedy 1982), a role culture, task culture, person culture (Handy 1985), caring culture, integrative culture, apathetic culture and an exacting culture (Sethia & Von Glinow 1986) all tended to ignore that culture is made up of human irrationality and emotion. Culture is in effect a multiplicity of complex conceptual structures, many superimposed or knotted into one another, which appear strange, irregular and inexplicit (Geertz 1973).

Edgar Schein (2005) defines organizational culture as "a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group has learned as it solved its problems of external adaption and internal integration that has worked well enough to be considered valid, therefore, to be taught to members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems." Organizational culture can be seen, felt, and observed through narrative, rules, offices, office layouts, furniture, written documents like mission statements, slogans, the way people dress, the way people react with each other and with those outside the organization, the way people work, peoples ideals, status and status symbols, the organization's heroes, traditions, peoples' emotions, and behaviors. Under this can be seen what is valued within the organization and the underlying set of beliefs members share. These are primarily at the conscious level.

Underneath peoples values and beliefs lay the underlying tacit assumptions of the organization, which are primarily unconsciously embedded within the members. These can be picked up through seeing what subjects and issues are taboo within the organization and finding out the "unspoken" rules that people follow. Looking at the difference in what is espoused through narrative and what is actually done by the by the organizations members also exposes deep assumptions (Argyris and Schon 1974). Culture produces paradoxes and inconsistencies that show up particular values like rewarding people, but at the assumption level take on different meanings like favoritism and/or control, which can have profound influence on the effectiveness of enterprise capabilities. Culture is also a field of power, which can either empower members or alienate them (Bourdieu 1988). An organizational culture is greatly influenced by the organization's leadership through their narrative, actions, style, and symbols. Different configurations of the above produce sub-cultures which can run consistently or counter to the prevailing dominant organization culture.

Certain types of culture delineate reflection, thought, spontaneity, impulsivity, an action orientation, no action orientation, risk taking, risk aversion, aggressiveness and being pro-active verses being laid back and passive, etc. Some cultures suppress conflict in the interests of harmony, while other cultures produce conflict which lead to new meanings, new directions, thus influencing the whole inertia of the firm (Bourdieu 1993). Cultures continually change with dynamic interplay between the organizations members, society, the environment, its leaders, and the results the organization achieves or fails to achieve. Culture provides a collective interpretation and assignment of meaning to the environment (Daft & Weick 1984, Morgan 1986, Smircich & Stubbart 1985, Weick 1979). An organizational culture has immense effects upon enterprise capabilities but at the same time is one of the most difficult aspects of an organization to understand and change.

The effects of culture can be seen by casual observation of an organization. For example, if one experienced the staff at an old Eastern European hotel in one of the old communist bloc countries during the cold war era, one would have found that the staff often appeared complacent and disinterested in guest problems as the state provided job security. Compare this to the enthusiastic staff on Asia's leading low cost airline Air Asia. Culture plays a role like an "invisible hand" in ensuring an organization's members adhere to rules and conventions and behave according to the norms of the organization.

Organizational culture can play a positive role in an organization. The prevailing culture ensures members follow formal and informal rules of conduct and social norms supported with powerful conforming forces, so efficiency, predictability and stability is assured (Morgan 1986, p. 131). Norms are created through enactment where they are tested, and the positive ones that reinforce success are retained and the negative ones that are unsuccessful or unimportant weeded out and rejected (Miller 1993). Eventually these accepted norms mould into shared meanings as beliefs and values. This process over time creates a generation of firm specific symbolic knowledge that success in the past and present has been obtained through. Thus culture links the past with the present and with a certain orientation that can be taken in the future.

Developing enterprise capabilities requires more than just assembling skills, personal competencies, assets and other resources together. Capabilities require complex patterns of coordination between people and the resources they have. Capabilities must become routines which are supported by the organizational culture to be effective. The effectiveness of capabilities requires cooperation and coordination within the membership of the organization and the values, norms, traditions, and leadership are all important in gaining member commitment (Grant 1991). Finally through the socialization aspects of culture, tacit knowledge gets passed on from member to member through specific use of models, symbols, analogies, metaphors and other means that "objectifies" implicitly (Schultz & Luckman 1985). Implicit knowledge is necessary for any capability to operate effectively.

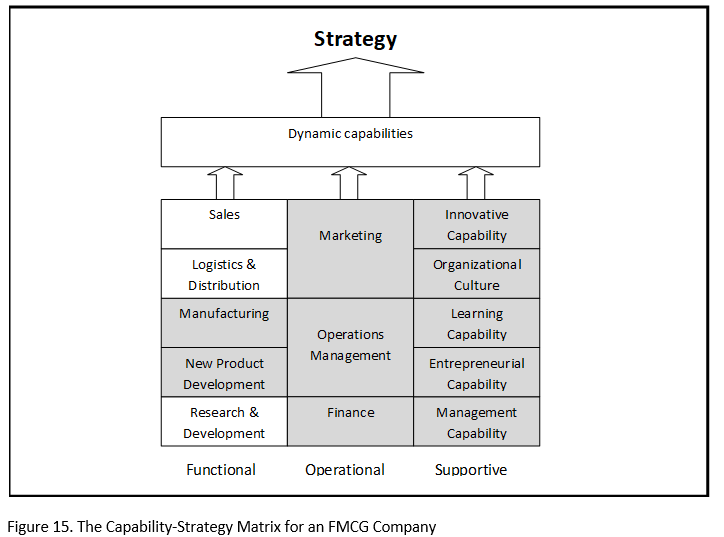

An organizational culture can also cause an organization to behave dysfunctionally and affect the firm's perceptions, performance, efficiency, effectiveness, and the ability to implement meaningful strategy. At the extreme, firms that rely on formal bureaucracy and rules for control tend to produce employees who fear superiors and spend their time trying to avoid censure. Fairness is achieved through impersonal rule creation that is orientated around reporting and measurement, i.e., time clocks and punch cards, etc. (Bies & Tyler 1993). Authority is top down, usually in the hands of "powerful people" who use intimidation to make employees feel they are beyond questioning. Bureaucracy and rules are also used to mask leaders' biases (Moore & Haas 1993), or to justify self serving actions. Consequently employees feel that they have little power and discretion and develop a sense of mistrust of the organization (Sitkin & Roth 1993). The poor congruence between competent people and the values and requirements of the bureaucracy may create feelings of alienation, despair, frustration, and apathy (Argyris 1957). As a result individuals may only perform to their minimum to satisfy organization requirements, refusing to do anything more for the organization than is necessary (Bateman & Organ 1983). This may result in employees creating dysfunctional work routines (15) to cope with their feelings of alienation which may emerge as covert sabotage of the workflow, or resignation from the organization, leading to the inability to exercise their enterprise capabilities effectively, affecting overall performance and efficiency of the organization (Martinko & Gardner 1982). When employees engage in behaviors that are negative to the organization, management may respond by tightening their controls on employees, creating a spiral of actions and reactions that can destroy enterprise capabilities (Lado & Wilson 1994).