Creativity is comprised of a combination of expertise, motivation and our creative thinking skills. Expertise includes all our knowledge and experience, including technical, practical, and tacit knowledge. There are various forms of motivation, but it is the implicit forms that are most influential in driving our will to be creative. Our creative skills and ways we think are important tools to produce a new idea or solution to a problem. Our creativity also depends upon our sensitivity, focus, attention, curiosity, imagination, energy and our ego.

However just as some factors promote the ability to be creative, creativity can be blocked and a person prevented from seeing new associations and solutions to problems. This can happen both to the individual, and at the social and organizational levels. This rest of this section will outline some of the individual and organizational blocks to creativity.

Early Creativity and Social Blocks

During our early years we tend to be uninhibited in what we do. Our drawings, acting (or mimicking) and views of the world may be naive, but uninhibited. We are imaginative and fantasize much more easily than when we are adults. In the pre-computer, TV and multi-media world, it was often our own imagination that kept us entertained building sandcastles, mud houses, cubby houses, doll enactments and plays, etc, imitating the world we know[1]. Our creative tools also helped us to make sense of the world we were growing up in through wishing, rearranging, structuring, and imagining. These tools are vital parts of the learning process.

As we get older and go to school we learn our logical sides and slowly drop the artistic and creative sides in favour of ‘life skills’. The memory retention orientation of our early education systems (and those still in Asia and Africa today) very quickly diminish our creative tendencies. Parent and society expectation put high value on professions like law, medicine, engineering, science and business. Art, acting, sculpturing, painting, writing and dramatic careers tend to be gauged as fantasy occupations that are not for the rational to pursue. The steering of career orientation and rejections, criticisms and humiliations during the early stages of our learning affect our views and can dampen any natural creative tendencies (Prince et. al. 2000). We are very sensitive to criticism, rejection and humiliation and in most cases usually willing to change our behaviour to maintain acceptance from others. We start to lose our creative skills like fantasy, imagination, wishing, transforming and comparing, replacing them with psychological blocks that in extreme form resemble various forms of psychosis.

Mental Models and Mental Blocks

Mental models are articulated concepts of how we manage our relationships, our interactions with the environment and our general view of the world. Our mental model is the sum of all our schemata and scripts, our total knowledge. Mental models act as templates to provide meaning to what we see in the world.

But just as mental models guide us, mental models tend to be relatively rigid and can also blind us to other potential possibilities. Our psych has a vested interest in rigidity because if our mental models are challenged by what we see, they can break down and lead to uncertainty and ambiguity where stress and anxiety will develop.

Conceptual blocks stop thinking processes through unconscious mental blocks. Mental blocks affect us in different ways, where various filters or patterning upon our perceptions or prevent us from letting ideas emerge from our sub-conscious (Prince 1998). Our senses are optimized for our everyday survival. For example, if we live in an area well known for snakes running across housing estates, we will tend to be alert for this type of danger. Many dangers to us are more subtle than that and our mind utilizes various strategies to protect the person.

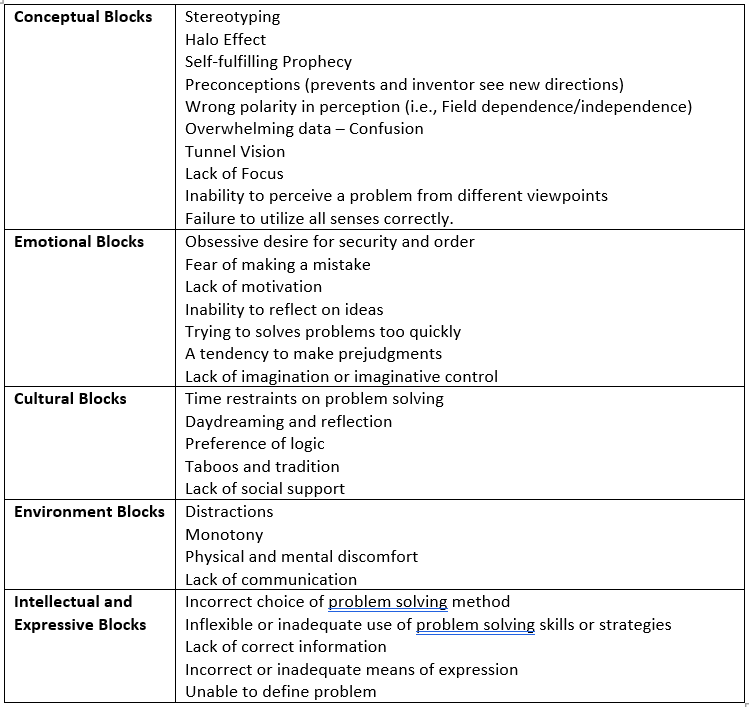

James Adams (1979) compiled a list of conceptual blocks, classifying them as perceptual blocks, which confuse data coming from our senses and disrupt the way our mind manages that data, emotional blocks where our emotions and desires interfere with our ability to form thoughts, cultural blocks that place acceptability limitations on what we think and do, environmental blocks where we incur physical distractions, and intellectual and expressive blocks which deal with problem solving strategies. Many blocks also have undesirable side effects because we utilize them as long term strategies rather than short term tactics when prehistoric humankind had to utilize fight/flight responses to mortal dangers. A summary of some of the different types of conceptual blocks are listed in table 1.

Table 1. List of Some Different types of Conceptual Blocks[2].

Some of the heuristics listed above assist an individual on an everyday basis to solve problems. They are short cuts in judgments that are convenient and save time by cutting down on the complexity. However the above listed heuristics can also prove to be great flaws in our perception and reasoning as they produce misconceptions[1].

Limited Domain Knowledge

Quite often our mental models are flawed, which often lead to individuals using the wrong analogies and therefore missing meaning (Kempton 1986). We often misunderstand how things really work and make decisions based on our misconceptions. Limited domain knowledge can handicap a person in being able to frame a problem (Proffitt et. al. 1990). Even if a problem can be framed, we may use the appropriate information, may use it inappropriately or fail to use the information at all to solve the problem. Instruction, training and knowledge in a domain assists our ability to reason within it. However that training within a discipline may not always eliminate misbeliefs (Kozhevnikov and Hegarty 2001).

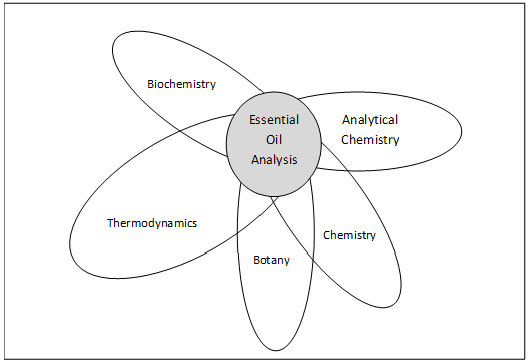

As technology becomes more advanced and problems require a multi-disciplined view to develop a comprehensive understanding, any single individual may lack the knowledge required to deal with the issues involved. Therefore greater reliance on teams that can look at issues from multiple disciplines is desirable. Professionals entering the workforce in the future are likely to have some background in more than one discipline. An example where multiple disciplines are needed is in the case of the analysis of essential oils from plants. Essential oils are natural aromatic substances derived from plants through distillation that exhibit a usually complex odour. To be able to analyze an essential oil, a person needs to understand the domains of chemistry, biochemistry, botany, thermodynamics, and analytical chemistry (Hunter 1994). The analytical equipment used in the analysis of the essential oil, a Gas Chromatograph Mass-Spectrometer may identify compound X as present. However our botany and biochemistry knowledge enables us to understand whether it is possible for compound X to exist, due to the way the plant synthesizes its metabolites. Consequently another compound with a similar structure may be present in compound X’s place, leading to the identification of a different compound (Hunter 2009, P. 160). Figure 1. shows the merging of domains that is required to analyze essential oils within plants. Many tasks are now extremely complex and require synergized views of problems to solve them.

Figure 1. The merging of domains required to carry out an essential oil analysis

Organizational Barriers

About half of new companies close their doors within the first five years of operations. Out of the five remaining, four will survive into their tenth year and three into their fifteenth year of operation (Birch 1987). Among the large corporations listed in the Fortune 500 between 1970 and 1986, almost one third vanished completely (de Geus 1988). Historically company excellence only lasts a short time, where the average life-cycle of a company is around 40 years (Collins 2001). Peter Drucker espoused that companies are only entrepreneurial in the early stages of their life, where after establishment they slip into the guise of being an ordinarily managed company (Drucker 1986).

A company’s decline does not usually occur from the lack of resources, information, knowledge or finance. The company’s decline occurs because of a changing environment that is not detected. To sustain a company new ideas are needed to exploit evolving and transforming opportunities, as well as develop the strategies required to achieve successful exploitation. This requires creativity.

Any opportunity has a limited lifecycle. As the opportunity drifts, companies require new technologies, new products and/or new ways in delivering products and services to maintain their relevance in the market. A company can only survive as long as an opportunity remains viable and the company is aligned with it. This may mean that new ideas and strategies based on new technologies, the development of products (and the cessation of old products), the entry into new markets or the development of new ways of doing business is needed to maintain that alignment.

Companies over time can become rigid and develop an egocentric manner. The management sees the company as the centre of the field, the market or industry leader where nothing can harm them. A number of conditions develop within organizations that make management within them lose their sense of adventure, entrepreneurship, and creativity. These conditions will be discussed in the following sections.

Compartmentalized Thinking

One of the characteristics of a maturing company is its division into compartments or departments which tend to influence how people within the organization look at the environment. People tend to take the points of view of their specialized departments. The fun that was shared through formation and early growth is switched for the more formal functional processes of production, procurement, administration, sales, marketing and finance, etc. Departmentalization discourages an environmental wide view of things, in favour of narrower departmental and disciplinary approaches.

Although specialization has always been assumed to bring efficiency, this is sometimes questionable from the organizational point of view. The potential efficiencies that can be gained from increased specialization can lead to the loss of interdisciplinary thinking within the organization, as people tend to look only from their departmental points of view. The disadvantages of departmentalization can be seen in the example of cars built in Detroit during the 1960’s and 1970’s where different sized bolts where used in different parts of the car, leading to increased costs and the need for more inventory items, just because the car was designed from different functional perspectives. This was in stark contrast to the Japanese cars that were manufactured with common bolts to streamline the production and procurement processes. Departmentalization can hinder company integration where departments become egocentrically concerned with their ‘turf’ and position, often leading to conflicts and power struggles within interdepartmental relationships. This diverts energy, focus and attention away from creativity towards maintaining the interdepartmental status quo within the organization.

Hierarchy

Hierarchy automatically builds in assumptions about how information flows, the nature of connections between the different components of the organization and outside stakeholders, and how power and influence operates. Organizations will also have a desired level of diversity within it, either by deliberate design, policy, or through the influence informal conformity to norms by those responsible for selecting new personnel[1]. An organization will also tend to have entropy towards the maintaining the status quo or being amicable towards continuous change.

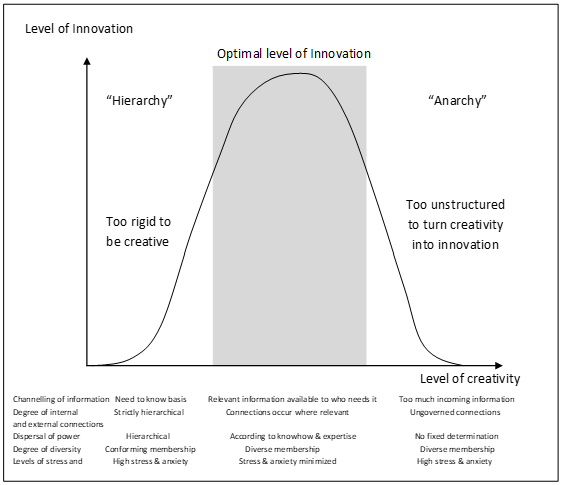

According to Stacey (1996) how organizations tackle these organizational dimensions will have enormous influence over the level of creativity and innovation. Information flows within a traditional hierarchy where authority is important will be on a strictly need to know basis. Information will be a protected commodity accessed only by those in authority. Ideas will flow from the top down the hierarchy, where the lower levels are only responsible for implementation under supervision. There will be no room within an authoritative hierarchy where power-distance is high for ideas to flow from the bottom up. In those types of organizations people are not expected to think outside established rules and processes. In fact thinking outside established rules and procedures would land a person into trouble.

In highly controlled organizations, communication up and down the various tiers is controlled and rigid. It is the prerogative of superiors to make any decisions that established rules and procedures do not settle. There is no room for alternative ideas or perspectives and anybody exhibiting alternative opinions would go against the norms of the prevailing conservative culture within the organization. Those with actual power are cautious in their decision making and people would be fearful of expressing alternative ideas in public. Consequently such organizations would create high levels of stress and anxiety for those employed within it. Such organizations would be very rigid and not know how to handle information that differs from what those within the organization are used to. This would just add to stress and anxiety rather than a cue for needed analysis and change. Subsequently any forms of creativity, except for dysfunctional behaviour would not occur within these types of organizations.

Creativity is best served by an organization that has unhindered flows of ordered information that can be accessed by all relevant people. Power is best based on knowledge and expertise rather than position or political positioning. Interdisciplinary groups of diverse people are encouraged to take a holistic view of problems and opportunities. Finally the organizational leadership would be open to new ideas from all parts of the organization and see change as a necessity for organizational survival.

However too much freedom at the other end of the continuum may allow too much unfocused creativity, where an organization would also be paralyzed through indecisiveness. In such an environment there would be information overload where it would be too confusing to determine what information is important and what should be disregarded. Alternative opinions are canvassed to the point that no decisions or commitments can be made. Groups within the organization may be so diverse that little common ground, that there may be little sense of common mission. Such an organization seeks change without having commitment and agreement about what change should occur. Although being a creative organization, none of its creativity results in any form of innovation because of lack of focus, discipline and formal decision making processes.

A graphical view of the continuum of hierarchy to anarchy within an organization is depicted in figure 2. On the left side formalized and authoritative hierarchies allow little room for creativity and innovation. These would include very production orientated organizations and companies that still subscribe to the concepts of scientific management. These may also include organizations dominated by a founder who wishes to make all decisions within the organization. At the other extreme is an organization in chaos where there may be great creative potential but no mechanisms to channel and focus creativity into innovation. Groups run into conflict over differing ideas where frustration develops. Many examples of this form of organization may be early start-ups made up of groups who find it difficult to make decisions. These organizations start moving once they are able to define how to channel and develop decision making procedures. The middle of the continuum is where organizations can be creative through allowing information flow, diverse groups to work on problems and authority based on knowledge and expertise. This is where innovation will be at the maximum because of focus and sense of mission within the organization. There will never be two organizations adopting exactly the same mix of organizational parameters. Each company will find from experience what works best for them.

Figure 2. Continuum of hierarchy to anarchy

Rigidity

Rigidity is a product of hierarchical organizations that are traditionally locked into operating through strict rules and procedures. Although rigidity has some advantages in sustaining individuals in times of stress and anxiety, rigidity is the true antithesis of creativity within an organization. Rigidity within an organization can come in many forms. Rigidity is caused from over-learning, where the same generalizations are applied to every problem facing the organization, with an intense attachment to rules, procedures and beliefs within an organization, especially conservative ones.

Organizations that don’t interact with the environment to protect themselves and rely on rules and procedures to operate regardless of what happens in the outside, tend to develop strong dogma as a unifying force (Rokeach 1960). Each member is expected to hold the shared set of beliefs that may be considered fanatical to outsiders. Only incoming information that supports the organizational dogma is acceptable where all other information is part of a conspiracy to undermine the organization or leadership. Within such an organization one would regularly hear comments like “this is the (name of the organization) way of doing things”, “around here we must do things like this”, or “outsiders don’t understand us and try to undermine what we stand for”. Organizations wrapped in dogma may border on the psychotic and there is some chance that members of the leadership are psychotic to some degree. Creativity within these organizations is seen as a threat to stability and is generally suppressed.

Rigid organizations may look at issues and people through stereotyped vision. Generalizations are made about the classes of people without evidence about their attributes or qualities. This leads to distorted views of the world like “all Muslims are terrorists”, “all Americans are anti Muslim”, “all Germans are Nazis”, and “all Australians are anti-Asian”, etc. Stereotyping helps to make the unfamiliar look familiar but suppresses our curiosity and ability to question about what we see. In the mild state, stereotyping is narrow mindedness, but in the extreme stereotyping is a symptom of psychotic behaviour. Adorno et. al. (1950) espoused that those harshly treated by someone in their childhood years may grow to adulthood with extreme hate for certain stereotyped groups of people. This can lead to the type of dogmatism discussed above.

Over-learning can cause functional fixedness, a state where a person can only see one conventional function or use for particular objects. Functional fixedness can often occur within professions where people will tend to rely on the training of their respective disciplines to solve problems. For example, a marketing person would look for a market solution, where a legal person may want to consider a legal solution. This form of rigidity prevents individuals from using objects and concepts in new ways, as he or she is locked into one specific use for the items or concepts in question. Thus individuals will respond to a problem in a fixed way rather than look at new possibilities. This prevents a person from seeing new connections and associations which blocks creativity. Functional fixedness is very common and requires a conscious attempt to break out of this type of thinking through CPS techniques discussed previously.

Fear and Conformity

If we sufficiently fear something, our capacity to be creative is greatly diminished. There are a number of sources of fear that take away our focus, energy and attention, dampening our curiosity.

One of our most common fears in organizations is that of uncertainty, the unknown and the ambiguous. Ambiguity, uncertainty and complexity discomforts most people who are unable to cope and develop stress and anxiety. Most people actually have a need for customs, procedures, rituals, routines, and traditions, etc., for security and stability. Even though this may cost many opportunities for personal growth the benefits of comfort and security are worth it in most people’s view. The roots of conformity go deep from the time of being reared as a child to what is socially right and wrong behaviour. Children are also taught the social severity of deviation. This is why conformity is difficult to let go easily where a person needs to question traditions, structures and be exposed to other dynamic cultures.

Fear is also a group phenomenon where the group develops beliefs, norms and values that bind people together. Breaking the group’s beliefs, norms and values will lead to sanctions from the rest of the group. Conformity is another form of organizational rigidity which hinders creativity (Parnes and Meadow 1963).

Another form of fear is the fear of failure. In a mild form the fear of failure is a strong motivation to maintain sharpness, focus on doing a better job that creates some competitiveness in a person or group. However in the extreme form it may prevent a person take any risks and play things safe by not taking on any activities that may appear risky to a person’s self image, should they fail at the activity. For example, a bad review for an artist may turn him or her off doing anymore works. Therefore people with a fear of failure will stick to undertaking tasks that avoid competition and there is certainty that they will win. People with a fear of failure will look for excuses of why they would fail and go into excessive fright and nervousness when there is some form of test situation. A fear of failure can retard divergent thinking and discourage people from undertaking new activities (Khandwalla 2004, P. 293).

People also fear criticism and humiliation. In the mild forms, some level of criticism can be motivational. Criticism or humiliation can have the effect of bringing groups into more cohesion (i.e., to defend against a common enemy). Other effects of criticism and humiliation create touchiness and resistance to innovative ideas. An organization that has an atmosphere of negative criticism will destroy employees’ intrinsic motivation to the point they will fear to present any new ideas (Amabile 1998, P. 83).

Defensive Routines

Defensive routines are actions or policies that protect us from fear or embarrassment of exposing our thinking to others. Defensive routines form a protective shell around a group or organization that shields any scrutiny or attack upon its general assumptions that may produce pain or anxiety. Defensive routines can prevent people in organizations from seeing things, solving problems and learning. For example, management may focus on making short term profits by cutting down on costs, even if this may threaten longer term profitability. The ‘O’-rings on the space shuttle Challenger were numerous times by the engineers who did nothing about them because it may threaten the program schedule, thus preventing any dealing with the matter before the tragedy occurred. When sales fall, managers responsible may jump in and develop a program of discounts and sales promotions, without looking for any reasons why sales are falling, thus failing to learn the fundamental reasons behind the sales downturn. All these events hide the reality and truth of the situation. Things are hidden because there is a fear that errors will be found by others.

Chris Argyris (1990) proposed that most behaviour in organizations is shaped by a set of ‘governing variables’. This means that people will strive to avoid embarrassment and threats by advocating views without encouraging inquiry, undertake actions that save face or are defensive, design and manage situations in order to maintain control, evaluate the thoughts and actions of others in ways that don’t encourage the testing of the validity of the evaluation itself, attribute causes for things without really validating them and encourage defensive actions like blaming, stereotyping, and intellectualizing to suppress anxieties.

These ‘governing variables’ don’t necessary match the values that people espouse, so there ends up being an espoused theory of action and an actual theory of action (Argyris and Schön 1974). The behaviour contradicts with what is espoused. The actions taken are based on stress and mistrust as an attempt to escape exposure for something wrong. This type of behaviour prevents learning, creativity and the development of innovative solutions to problems facing the organization.

Complacency

Complacency was discussed in part II in relation to the concept of opportunity. But complacency also has an effect on creativity. When a company is immersed within the same environment on an everyday basis, this brings familiarity, where familiarity brings insensitivity to detecting any small or modest change. This is very important to seeing new opportunities. One of the best examples of blindness caused by complacency was the US car industry which didn’t take much notice of the Japanese car makers when they came to the US in the 1960s. It was only when the Japanese car makers gained more than 20% market share in the 1980s, the US car makers woke up to the threat and changing opportunities. The US car makers were hesitant to move into the new market segments created by the Japanese car makers, and became unable to innovate. Blindness due to complacency develops a lethargic attitude towards the need to be creative and innovative. Complacency is a primary reason why companies decline and completely disappear from the market place.

Time and Resources

Organizations most often operate according to schedules. Work hours are scheduled, breaks are scheduled, projects run according to timetables and product launches are timed. Schedules have advantages in that they create some pressure on an individual’s performance, something like when swatting for an upcoming examination at school, where there is a deadline to be met. If there was no deadline, most probably there would be little pressure to study. The effect of competitive and time pressure was partly responsible for the breakthrough in World War II, the arms and space race between the US and USSR during the 1960s. However continuous tight deadlines can turn into mistrust, where employees feel over controlled and eventually burnout.

However creativity requires time and tight deadlines can kill creativity. Many problems are only solved after a period of intense work without making any progress, where insight will come after a person has stopped thinking about the problem. Unfortunately the timing of insight cannot be controlled to conform to schedules. For serious creativity to occur time is needed for exploration and incubation. The pressure to solve problems quickly is a major obstacle in solving problems as they require insight to solve them. Tight schedules also undermine technology or new product breakthroughs that need to occur from continuous experimentation and trial and error.

The correct resources are also needed to develop creativity. Work groups should have the right diversity and backgrounds within them with an interdisciplinary scattering so there can be a diversity of perspectives. Homogeneous teams may tend to reach compromise solutions avoiding intergroup conflict. There must also be the resources necessary, i.e., labs, office space, funding and time, etc. for the group to do their job. This includes the right physical space so work can be undertaken efficiently. However too many resources and facilities can also hinder creativity by developing an isolated comfort zone. Many breakthroughs have come from individual inventors with very limited resources, rather than large corporate R&D labs.

Organizational Culture and Management Style

The prevailing organizational culture and management style of a company has a major impact upon the creativity of the organization. The general beliefs and values within the organization are greatly influenced by the management style practiced within the organization. Management style may either encourage or hinder creativity. Teresa Amabile (1998) proposed that management style influences employees’ sense of challenge, freedom, availability of resources, work group composition, supervisory encouragement and organizational support for creativity.

Teresa Amabile believes that managers don’t always match the most suitable people to an assignment to optimize creativity. Often people with the wrong expertise and motivation are given jobs that are not suitable for them. Once people have been allocated a task they should be given the maximum freedom to undertake the job, i.e., authority and responsibility. This allows employees to work on the problem with their own expertise and creative skills and develop intrinsic motivation along the way, where they can gain a sense of ownership. Managers often fail to define clear objectives and give true autonomy to a job, thus hindering creativity.

The amount of resources allocated to a project can support or kill potential creativity. The assembly of problem solving or idea generating groups is very important where a diversity of views and perspectives can be gained. This requires putting people together that have different intellectual bases and creative styles. Amabile (1998, P. 83) considered it very important the group members share excitement, help their teammates during difficult periods and also recognize the unique knowledge and perspectives of the other members. To be able to assemble such groups managers must have a deep understanding of their employees. Selecting a homogenous group will tend not to be as creative as a diverse and motivated group, which can be very powerful if differences don’t turn into conflict. The best atmosphere to provide for this group is one of supervisory support that underlines to the group that their work is important to the organization. Managers will quickly kill creativity if they criticize new ideas, give across the attitude of skepticism, or take a long period of time to respond. Finally, creativity is enhanced when a whole organization is supportive of it. Organizations that make creative people the heroes will put a positive emphasis on creative behaviour. Very few organizations actually have this positive attitude towards creativity. This is particularly the case where many people see giving criticism to others is a way to look intelligent to the boss. Problems then start becoming considered in the light of political gamesmanship. These organizational dysfunctions take attention away from work and clutter up open communication with gossip and games, destroying the potential for positive collaboration.

Other Blocks to Organizational Creativity

There are a number of other potential blocks to organizational creativity, some of which were discussed at length during part II of this book. Leaps of abstraction are very quick generalizations made about situations. These generalizations impede an objective view of the environment and situations that may occur within it. Groupthink and collective thinking, especially within homogeneous groups often lead to the suppression of ideas and information people for particular reasons don’t want to hear. This leads to failure for the group to canvass the important issues and less than optimal decision making. The benefit of collective thinking in many cases may be a fallacy according to De Bono (2002), where a person working on their own may produce a lot more new ideas than those working in a group.

To build a creative organization actually requires an understanding of what management factors foster creativity and what impedes creativity. Creativity within an organization needs;

· Expertise and interdisciplinary knowledge – technical, procedural, formal, informal, practical experience, and intellectual thinking. There must be interaction with other professionals to develop interdisciplinary approaches to generating ideas and solving problems.

· Motivation – inner passion to find and solve problems, where this motivation should be intrinsic rather than extrinsic.

· Time to enable incubation of ideas or undertake exploration through trial and error, and

· Creative thinking skills to enable flexibility and various methods to look at and solve problems as well as generate new ideas.

To be creative in the organizational sense, the idea or solution must be appropriate, useful and achievable. It must influence the way business is done, improve productivity, or show a new way of doing something.

[1] For example, domineering leaders may tend to select people who will follow passively and are of the same social background, while high-tech start-up companies in Silicon Valley may select people based on knowledge and ability, regardless of social background.

[2] For example a pilot in night flight may have great difficulty in judging the distances of objects from the aircraft and personal orientation to the horizon. In this situation the pilot’s senses are confused and therefore must rely upon flight instruments rather than senses for information.

[3] The children of the Millennial generation are now going to school. They are much more impatient than previous generation and don’t have the same discipline, although they are experts with new technologies. They have been brought up with more gadgets and money than previous generations and their play has been almost entirely with today’s technology. Millennials have a strong desire to succeed and do things their own way (Carlson 2005), but how creative this generation is still up to debate.

[4] Most of these are discussed in detail in Chapter three.

An extract from Opportunity, Strategy and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 1, Nova, New York, 2012, Chapter 4, pp. 473-484.

Subscribe Below:

Thank you Murray, very interesting and written in language I understand.