The evolution and influence of thinking in management Part 5: Management

An unpublished series of management ideas

The fifth part covers ideas and practices which have shaped the way we think about management today.

Management Thought

World events and media portrayal of Islam over the last few decades has projected negative images, which are based on a total misunderstanding of Islam and the principals it encompasses[i]. Predominantly, Islam through many eyes is seen as a homogenous view of the world, where many elements of the media have stereotyped[ii] it as an extreme religion. This situation has not been assisted by the lack of published academic and intellectual thought[iii], which could assist in developing more balanced views about what the principals of Islam stand for. The focus of most published works on Islamic economics and business has been in the domains of finance and morals[iv], which leads most to the conclusion that Islam has little to contribute in the theories of economics and business.

The first and most comprehensive model of Islamic economy in modern times was published by Dr. M. Umer Chapra in the early 1990’s. His hypothesis was that existing economic models of capitalism, Marxism, socialism and the welfare state have failed to provide full employment, remove poverty, fulfill needs and minimize inequalities of income distribution. Both the market and centrally planned models have been weak in providing overall wellbeing, where problems of family disintegration, conflict and tensions, crime, alcoholism, drug addiction and mental illness have indicated a lack of happiness and contentment in the life of individuals. Dr. Chapra stated that a new system needs to be considered which could optimize human wellbeing and presented an Islamic model of economy, which never been tried or implemented in any world economy and has potential to solve common economic problems due to the overall humanitarian goal of achieving the wellbeing of all members of society[v].

Dr. Chapra in an on-line interview was very critical of the development of Islamic economic and business theories claiming they were unbalanced in their approaches. He was reported to state that “Primary attention has been given so far to Islamic Finance. This has led to the false impression that interest-free finance is all that Islamic Economics has to offer. Since most of the governments in Muslim countries are not yet convinced that interest-free finance is workable, excessive emphasis on it has created a resistance in official circles against Islamic Economics. They find it to be of little value. This is unfortunate. We must blame ourselves for this. Islam is a complete way of life and is capable of solving the problems of not only Muslim countries, but also of mankind”[vi]. In the same interview Dr. Chapra said that it was the responsibility of Islamic intellectuals to show how Islamic economics could solve the socio-economic problems that humankind faced. This is in great need because there is a distinct lack of theoretical and empirical analysis to show that an Islamic strategy can help solve economic problems, particularly with the current state of the Islamic world, where there is decline in moral values, exploitive financial systems, illegitimate governments, landlordism, lack of education, absence of justice and ineffective operation of incentives and deterrents. Dr. Chapra believes that there is great repetitiveness in what is written about Islamic economics which is not serving any cause. An Islamic alternative needs to be spelt out, which can only really be done after the real position in Islamic countries is analysed, i.e., how individuals, families, firms and governments actually behave, so the gap between ideals and reality can be measured and Islamic remedies developed.

The message of Islam forms its basis from the Al-Qur’an, which is the direct word of Allah (S.W.T.). The Hadĭths are documents made up of lessons taken from the life of the Messenger Muhammad (S.A.W.), written down by a number of apostles, which put the knowledge from the Al-Qur’an in both context in which they were revealed and assist in developing a general and universal significance[vii]. Without the Hadĭths many important aspects of Islam would not be known today and the Al-Qur’an would be at the mercy of those who misinterpret it[viii].

To date “The fanaticism and prejudice for Western managerial systems have also, among other things, veiled the relevancy of Islam as a model of management, as well as generating a cynical reaction that the Islamic model existed in history and concept only, but never practiced in modern life, even by countries with a Muslim Majority”[ix]. Islamic scholars argue three main reasons for the need to develop and implement an Islamic business framework;

The nature of man: Man has both the potential to rise to great spiritual heights and also disintegrate into total immorality. Man’s ability to act rightly or wrongly is a matter of moral choice. Under the Islamic viewpoint, man’s purpose on earth to carry out ibadah (relates man to Allah {S.W.T} through spiritual acts)[x] and follow God’s will with total devotion, according to his natural disposition (fitrah); where everything fits into the divine pattern under the laws of Allah (S.W.T)[xi]. Submission to the laws of Allah (S.W.T) brings harmony to man, however man was created with many weaknesses[xii], forgetfulness[xiii], greed for material comforts and power[xiv], is capable of oppressiveness and ignorance[xv], is rash and impatient[xvi], stringy and miserably[xvii], ungrateful[xviii], quarrelsome[xix], ruthless[xx], and full of self interest[xxi], which can easily lead him astray.

The amoral society: General society has become amoral and lapsed in faith, believing that truth and reality is based on what can be touched, smelled, seen, heard and tasted. This has lead to a society that has become materialistic and less spiritual. This absence of spirituality is leading business into immoral activities such as stealing, lying, fraud and deceit, making people believe that they cannot succeed without pursuing the same practices[xxii].

The underdevelopment of Islamic societies: Approximately 80% of the World’s Muslins live in poverty, as cultural minorities in other countries, with high incidences of unemployment and low productivity[xxiii]. Countries with majority Muslin populations, are declining in their knowledge generation, research, innovation and educational standards[xxiv], have a generally a lower life expectancy, higher illiteracy rates, lower GDP per capita rates with the majority of people living in fragile and non-arable lands, poorer infrastructure and water supplies and a larger number of dependents than the non-Islamic World[xxv]. Islamic GDP as a percentage of total World GDP is estimated to be only 45% of what it should be, in order to be on par with the rest of the world[xxvi].

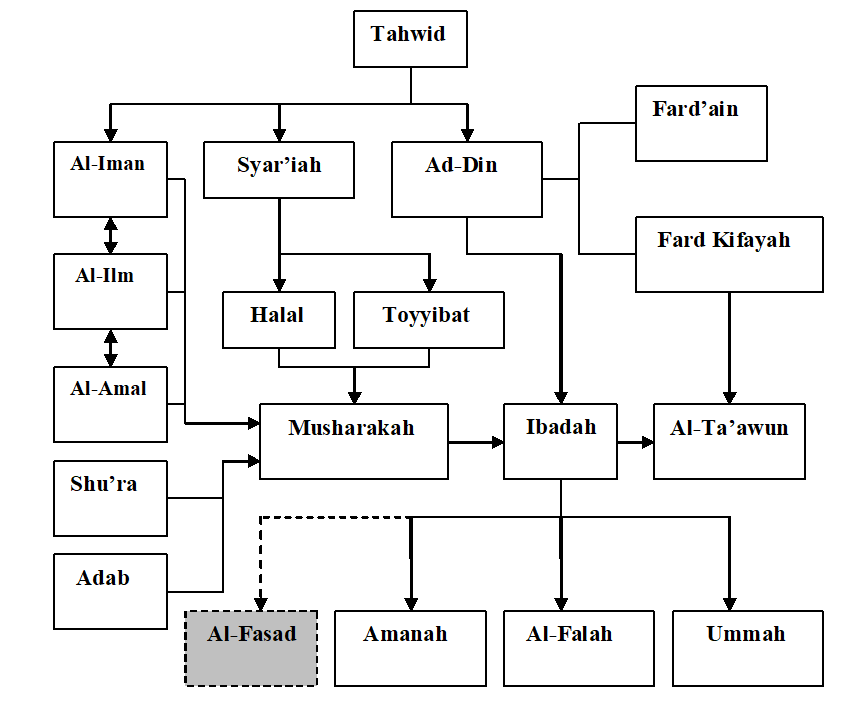

The basic Islamic principals and their interrelationships are shown in figure 1.x below.

Figure 1.x: An Islamic Business Framework

The Al-Qur’an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (SAW), who was born into a trading family and brought up by Abu Talib, who was a trader. Society in the Prophet’s time was almost totally dependent on trade as a means to earn a living and unlike any other religion, the Al-Qur’an is heavily written in the metaphor of business and trade. Within many parts of the Al-Qur’an life is paralleled to a business venture, where one earns profits to gain entry into heaven – profits meaning faith and good deeds to others and those that accept Allah’s (SWT) guidance as a bargain to save them from punishment on judgment day[xxvii]. Islam urges individuals to strive their utmost to earn large monetary rewards and spiritual profits, while at the same time being inspired to be successful and honest people[xxviii]. This is part of the concept of ad-din, which makes material and spiritual pursuits inseparable, where one’s whole life is concerned with the needs of humankind here on earth to secure a comfortable life in the Hereafter[xxix]. Consequently, Islam does not prohibit worldly success[xxx], in fact Allah (SWT) has provided opportunities for humankind to obtain success and it is certainly the responsibility of the individual to do so[xxxi]. However involvement in business should also carry with it benevolent intentions for others while seeking success for oneself[xxxii].

Islam espouses a market economy with freedom of the individual to operate a business with minimal outside interference;

“He who brings goods to the market is blessed with bounty, he who withholds them is cursed.”

(Ibn Majah & Al Hakim)

A market mechanism is urged with free flowing knowledge without exploitation by middlemen;

“Do not chase after those who are going to the market before they reach the place.”

(Al-Bukhari & Muslim)

Islam also prohibits price manipulation;

“Anyone who withholds goods until the price rises is a sinner.”

(Muslim).

Thus Islam espouses that free trade is a major factor in the enhancement of living standards of the general community, subject to some constraints on business in the interests of the wider community.

Central to Islam is Tawhid “…a man’s commitment to Allah, the focus of all his reverence and gratitude, the only source of value. What Allah desires for man becomes value for him, the end of all human endeavour[xxxiii].” Tawhid is the Islamic way of life, the fundamental of all Islamic civilization, which is process, means and end together. Tawhid is both the essence of the individual and the society he or she lives in. Tawhid is acceptance of one creator and His divine guidance of humanity[xxxiv]. Tawhid implies both the mission and morality of humankind in both social and spiritual contexts.

Mankind’s responsibilities under Tawhid fall into two categories, fard’ain which is an individual’s obligation to perform his or her religious duties and fard kifayah, which is an obligation for man to serve the entire community, through services to each other, necessary for the community to live safely and comfortably. Thus the obligation to improve the Muslim Ummah (community) falls under fard kifayah[xxxv], where undertaking business is the principal method[xxxvi] of improving the economy and community;

“Be involved in business as nine out of ten sources of income lie in business”

(Ihya)

The building blocks of Tawhid are the concepts of al-iman (belief), al-ilm (knowledge) and al-amal (pious acts and efforts). Al-iman is the belief in the existence of one God and Creator, with a commitment to His teachings and revelations, revealed through the Al-Qur’an, and Prophets, through the Hadĭths and Sunnah (What the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) said, did, agreed or disagreed to). Our faith in Allah (S.W.T.) is reflected in our daily behavour, influenced by our moral system formed and contained within us. It is our inner self;

“Faith is not expectations and not outward ornamentations, but implanted in the heart and realized through actions.”

(Ibn Najjar & Dailami)

Al-iman is deepened by al-ilm[xxxvii], which is the responsibility of all Muslims to seek[xxxviii] in order to fulfill and perform al-amal. Knowledge (spiritual, wisdom and scientific) is the foundation of all acts of al-amal which would be futile and unproductive without the search for further knowledge[xxxix] to enhance the wellbeing of society[xl]. Islam places great importance on scientific discovery, knowledge and wisdom to develop civilisation[xli]. Al-iman and al-ilm manifested through al-amal is the basis of the advancement of civilization for the benefit of humankind and the Ummah (Muslim community), in particular. This is undertaken under the principal of ad-din, mentioned above, which is referred to as ibadah.

In Islam a person, who of faith, knowledge and pious devotion, manifested in effort and acts, using reason and experience and adheres to the teachings of the Al-Qur’an and Prophets is a person of Taqwa, adhering to the philosophy of Tawhid. He is fulfilling his purpose on earth to perform ibadah[xlii] to God, through obedience (ta’ah), which conforms to his true and essential nature (fitrah) of man. This relates man to God through everything an individual does, including spiritual duties, thoughts, actions and deeds to other people[xliii].

As man operates in a social environment, Islam prescribes a number of forms of business organization, through which his obligations can be fulfilled. A mushharakah can take a number of forms;

a) Mudarabah: Partnership where one manages the partnership and another supplies the financial support,

b) Shirkah: where two or more individuals pool financial resources and share profit and loss on an agreed ratio and held liable to the extent of their capital, and

c) Syari’ah: each partner is able to operate other businesses, independent of the principal business.

Such business organizations are founded and operated on the principal of al-ta’awun (mutual assistance and cooperation) among members of a society for both their mutual benefit and that of a society as a whole[xliv].

Islamic business is governed by the rules of syar’iah, the path by which all Muslims should follow. The syar’iah is the divine law that establishes the standards of justice and human conduct, as well as what is permitted and prohibited in action. The syar’iah is based on the Al-Qur’an, Sunnah and interpretations by Islamic scholars. Some Muslim scholars have stated that these standards are beyond human and are a goal or path of guidance[xlv], where others see these utopian ideals as mandatory for advancement of the community[xlvi].

Central to the syar’iah are the concepts of halal and Toyyibat, which govern all the economic activities of man in wealth production and consumption of wealth, where certain means of gaining a livelihood are declared unlawful[xlvii]. Halal means lawful or permitted for Muslins[xlviii], a concept that is much wider than just issues of food, concerning as to whether things are undertaken according to the syar’iah[xlix]. Toyyibat is a much wider concept, meaning good, clean, wholesome, ethical in the Islamic concept. In nutrition, toyyibat is much wider than halal, as food must also be clean, safe, nutritious, healthy and balanced[l]. Toyyibat would also mean that agriculture must be undertaken within sustainable practices[li], and in business that things are done with good intentions[lii].

In Islam, the individual’s vision, mission and objectives in business is to achieve both success in this world and the hereafter. This is al-falah. Islam puts very little restriction upon the scale of worldly success[liii], except specifying, it must be reasonable, provides the comforts of worldly life[liv], with consideration to the poor and suffering[lv], and within the balance of worldly and spiritual life[lvi]. Mans success must also serve the legitimate needs of the ummah[lvii]. This is in great contrast to the singular objective of profit maximization in contemporary business thinking[lviii].

Allah (S.W.T.) equipped man with the faculties of understanding right and wrong, so that he may obtain a bright destiny[lix]. Man has a free choice in what he chooses. Opposition and straying from his true nature (fitrah) will bring discord to the individual where negative attributes will distort his true nature, which could lead him into doing evil deeds[lx]. The individual has his al-iman and al-ilm to keep him from this path of self destruction (al-fasad), which would manifest itself through nepotism, favourtism, envy, greed, corruption, injustice and ignorance[lxi]. This in Islam is the influence of satan, manifested in many different ways to man to lure him away from God’s chosen path for him. Man becomes unfocused through ignorance and lack of knowledge[lxii].

Achieving al-falah means that man has lived up to God’s trust placed upon him, through performing his ibadah, while obeying all the laws of the syar’iah. This is where man has overcome his weaknesses in the service of Allah (S.W.T.) through righteous deeds (amal), in his obligation of fard kifayah. Man has reached the state of amanah, fulfilling the trust God has put in him[lxiii].

Islam also specifies the way organizations should be operated and managed. As discussed, an organization must base all its work on al-amal and ibadah with the overall management objective of achieving al-falah for the organization as a whole and each individual within it. This is based upon a foundation of al-iman and al-ilm, within a civilization based upon a tawhid philosophy, so that employees have the opportunity to achieve taqwa and avoid straying towards the state of al-fasad. Central to achieving this are the concepts of shura (participation in decision making and community learning) and adab (justice and rights).

Shura is total organizational community participation in decision making to ensure an organization gets the best views, is creative, to develop employees understanding of decisions made, to achieve better implementation of decisions and strengthen the Islamic fraternity[lxiv]. Shura is can also be seen as a organizational control mechanism to prevent management and individuals within the organization from straying down the path of ignorance, greed and oppression[lxv], so that the organization can continue to serve its members and the wider community and thus sustain itself. Shura creates a positive learning environment within and organization, similar to the concepts of learning organization discussed later in this section. The Al-Qur’an states that the concept of shura is mandatory upon an organisation[lxvi].

An organization should build its foundations upon the basic principals of human rights in its administration based on the concept of adab. Adab is based on the existence and recognition of Allah (S.W.T.) and recognition of his commands and laws (syar’iah). Within an organizational context, adab persuades man to do good and avoid evil (al-fasad), in accordance with the nature of man (fitrah) and nature of his action (al-amal). Adab comprises four major responsibilities, 1. responsibility to God, 2. responsibility to oneself, 3. responsibility to society and other human beings, and 4. responsibility to the universe and other creatures[lxvii].

Over the last few decades Western management ideas and ethics have moved closer to Islamic principals and ethics. The concepts of Islamic business and the ethical issues involved will be discussed in depth in chapter 26.

Henry Fayol was the manager at Comambault, a well known French company in the 1880’s which was heading towards bankruptcy when he took over. Fayol managed to turn the company around and upon his retirement, began preaching his theories of management[lxviii], later to be known as process approach (also known as universal, functional, operational and classical approach). Fayol’s principals were underscored by Taylorism at the time, but had a much more humanistic approach to management, believing in incentives through profit sharing for motivation and training of workers, etc. Fayol identified four features of an organisation as;

Specialisation: Work should be organised into logical functional groupings,

Unity of Command: Every employee should report only to one supervisor,

Chain of Command: Starts with the person in charge (managing director, CEO) and finishes with the least skilled employee, and

Coordination of Activities: Use of communication methods (memos, meetings, etc) to ensure communication between specialised groups.

Fayol identified five functions of management; planning, organising, staffing, command and control, which should be undertaken according to fourteen principals;

Division of work: Work should be specialised,

Authority: The right to give directives and expect compliance,

Discipline: Obedience and respect with reward and punishment systems to support,

Unity of command: The receiving of orders from only one superior,

Unity of direction: One superior and one plan for a group,

Subordination of individual interests to general interests: An individual’s or group’s interests should be subordinate to the organisation,

Remuneration: Fair and equity payment for work,

Centralisation: The size of the organisation should be taken into account when deciding whether decisions should be made centrally,

Scalar chain (line of authority): Communications should normally flow up and down the organisational hierarchy, but lateral communications should occur as long as superiors are kept informed,

Order: Everything in their place and a place for everything,

Equity: Personnel must be treated with kindness and justice,

Stability of tenure of personnel: to avoid rapid turnover of personnel,

Initiative: All employees should be encouraged to exercise initiative within the limits imposed by superiors, and

Esprit de corps: Harmony and union among employees.

Henry Fayol

Fayol’s work, even a century later appears very relevant to management and influenced many other theorists over the years, such as Luther Gulick’s POSD-CORB classification of management functions[lxix], George Terry’s classification[lxx], Koontz and O’Donnell[lxxi] and Urwick[lxxii]. Some of Fayol’s concepts were implemented at Genral Motors by Alfred Sloan. Fayol’s principals were accepted in France, but unheeded in the US until after 1949, when his book was published in English[lxxiii]. In the opinion of Luthans, “Fayol made a significant, if not the most significant, contribution to an overall theory of management[lxxiv].”

Mary Parker Follet was a political scientist in the first half of the 20th Century and was interested in extending the influence of democracy into industrial organisations, which see saw were ironically totalitarian in a democratic society. Follet argued that managers had a primary responsibility to develop a situation where people are able to make contributions of their own accord. Managers should learn by their own experience and call in specialists where necessary to contribute to the overall organisation[lxxv].

Mary Parker Follet

Follet was also interested on the influence of organisational political power on decision making and postulated that disagreements can be settled in three ways; by domination, where one party imposes a will upon another, by compromise, where each party gives a little to the other, and by integration, where parties invent a solution that better accommodates all parties[lxxvi]. Follet favoured the last form of solution as she believed that solutions could not be sustainable if they were zero-sum.

Follet’s ideas influenced many areas of management, in the areas of decision making, organisational politics and industrial democracy, which was experimented with by a few firms in the 1960’s and 70’s[lxxvii]. She developed the idea of win-win negotiations which was the subject of many books in the 1980’s and was an early developer of the theme of reconciliation for the development of value, that Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner postulated in the 1990’s, discussed previously. Probably her biggest contribution to management was her arguments about a much needed humane approach to management, which was needed at the time to counter the influence of Taylorism on American industry.

Follet’s ideas at the time fell to death ears except for a few notable exceptions like Marks & Spencer[lxxviii] in the UK and Levi Strauss & Co.[lxxix] in the US. However it was the beginning of a period where a number of studies and ideas were to take place and be developed, that would have great influence on future management thinking.

Elton Mayo, an Australian researcher in the United States was investigating the reasons for high employees turnover at the Philadelphia Textile Mill in 1923 and 1924. After interviewing and consulting with employees, Mayo’s group set up a number of rest periods during work which resulted in reduced turnover and more positive work attitudes. At the same time a scientific management study was being undertaken at the Western Electric Plant in Hawthorne, Illinois. Between 1924 and 1927 these studies examined the effect of lighting illumination, which would be expanded upon and continue into the 1930’s. The experiments were intended to examine the effect light intensity on productivity and expected to see a direct correlation between light intensity and productivity. However to their surprise, the researchers found that no matter the light intensity, productivity would increase. Something else was influencing increased productivity. This led to a completely accidental discovery. The research group concluded that it was the novelty of the situation that was the factor in increases of productivity[lxxx]. The studies continued with Elton Mayo joining the group, which experimented with changes in job design and pay incentives as new variables. The results indicated that pay schemes and incentives were not as importance as group influence on productivity in the workplace through the norms they develop. Group norms developed to protect the group in the organisation from external influences such as management. For example, the group would restrict production out of fear they would work themselves out of a job or that management would raise quotas. The group developed it’s own sanctions against errant members through ridicule, ostracism and name calling.

Elton Mayo

The Hawthorne studies is the single most important research breakthrough in management theory during the 20th century. The results showed the importance of the informal group on productivity and satisfaction in the workplace and issues like job security can be considered more important than financial rewards. Mayo himself argued that self esteem was vital to performance and management must take account of human nature as social motives. Failure to do this will lead to lower productivity, through covert activities like restricting production or in extreme cases sabotage[lxxxi]. Consequently, non-directive styles of supervision would be best to promote harmony and avoid conflict, allowing strong interpersonal bonds between the group members to develop as a means of satisfying social needs and inducing high productivity[lxxxii].

Industry didn’t jump on the bandwagon over these new ideas, however the knowledge gained from the Hawthorne studies was set to influence a number of thinkers in the development of management thought including, Macgregor, Maslow, Herzberg, Schein, Arygris and Bennis, in the formation of what is called the human relations school of thought.

In the discipline of psychology, Henry Murray was an author of one of the first textbooks on personality. Murray was one of the first to develop a model of motives and their relationship with behaviour. His model was developed for the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to evaluate the motives and access potential behaviours of world leaders. Murray believed that people rarely do things for a single reason, their unique range of needs had many levels where some dominated more than others. For example, a high need for dominance, coupled with a low need for intimacy would develop leadership behaviour where the person would have little regard for the feelings of others. In contrast, a person with a high need for dominance, but accompanied for a medium need for intimacy, would be more considerate about the feelings of others. A description of Murray’s Five categories of needs is below[lxxxiii];

Ambition Needs

Achievement: to master, manipulate or organise others, objects or ideas.; to accomplish difficult tasks rapidly and independently; to overcome obstacles and excel; to suppress rivals by exercising talent,

Exhibition: to be seen and heard; to be centre of attention; to make impression on others; to excite, fascinate, entertain, intrigue, amuse, entice, or amaze others,

Order: to put things in orderly arrangement, to desire cleanliness, organisation, balance, neatness and precision.

Needs to Defend Status

Dominance: to seek to influence or direct the behaviour of others by persuasion, command, suggestion or seduction; to control one’s environment, particularly the social environment; to restrain of prohibit others.

Needs Related to Social Power

Abasement: to accept injury, criticism and blame; to submit passively to external force; to resign oneself to fate; to admit inferiority, error or wrong doing; to confess and atone and seek pain and misfortune,

Aggression: to overcome opposition forcefully; to avenge an injury; to attack, injure or kill another; to forcefully punish or oppose another,

Autonomy: to shake off restraint; break out of confines; to get free; to resist coercion and restriction; to avoid being dominated; to be free to act according to one’s wishes and to remain unattached,

Blame-avoidance: to avoid humiliation at all costs; to avoid situations that may lead to embarrassment or belittlement; to refrain from action because of fear of failure or worry over scorn, derision or indifference from other.

Social Affection Needs

Affiliation/Intimacy: to enjoy cooperation or reciprocal interaction with others; to draw near others; to please and win affection of those like you; to remain loyal to friends,

Nurturance: to take care of others in need; to give sympathy and gratify the needs of helpless others, such as a child or someone who is weak, disabled, inexperienced, infirm, humiliated, lonely, dejected or confused; to assist persons in danger; to help, support, console, protect, comfort, nurse, feed and heal others,

Succor: to receive aid from others; to have one’s needs gratified by another; to be nursed, supported, protected, advised, indulged, loved and consoled; to always have a supporter or devoted protector.

Murray also developed a test of peoples’ needs and motives through their perceptions of the world, called the Thematic Appreciation Test (TAT)[lxxxiv], which was one of the first types of personality tests ever developed.

Henry Murray

Murray was a very respected psychologist. Although his work isn’t featured much in psychology literature today, he was a great influence on many others in this area. Murray’s TAT test is one of the most cited psychological tests ever[lxxxv] and a forerunner to many other psychological tests, including the numerous ‘entrepreneurial attribute’, ‘suitability’ and ‘personality’ tests, published in entrepreneurship texts today. Murray’s work has very rarely, if ever been applied to management, most texts preferring the work of Hertzberg, Maslow and others. Certainly Murray’s Needs Hierarchy has never, to the author’s knowledge, been applied to the much researched question in entrepreneurial research; ‘why does a person become an entrepreneur?’ Murray’s model may be a good way to look at this issue, especially in Malaysia, where culture has a more collective than individualistic orientation under Hofstede’s classification of culture, discussed previously.

Management approaches to motivation in the workplace during the 1940’s were simple and clear cut, seeing worker motivation as a result of monetary incentives, job security and good working conditions. Such a simple approach to solving complex issues was falling short. The only other alternative was the democratic principals of management, which were not acceptable at the time. Little had been done to apply psychology to business behaviour, at the time.

Abraham Maslow, a clinical psychologist realised there were higher needs that people perceived which influenced motivation. Maslow outlined a complete theoretical model of needs and motivation in 1943[lxxxvi], drawing upon his clinical experience as a psychologist. He believed needs could be arranged in a hierarchical manner, where once a set of lower needs had been satisfied, they no longer served to motivate the individual and a set of higher level needs become important to motivate the individual;

1. Physiological needs: are the most basic level in the hierarchy, which correspond to hunger, thirst, sleep, shelter and sex, etc. Once these basic needs are satisfied, they no longer motivate the individual. Only the next level of needs will motivate.

2. Safety needs: are the second level of needs that an individual seeks such as emotional security and safety. Like physiological needs, once they are satisfied, they no longer serve to motivate the individual.

3. Affiliation and love: are the third level of needs which concern an individual’s acceptance and belongingness to a group and society.

4. Self esteem needs: this is one of the higher levels of individual needs where power, achievement and status become important. This level includes both self-esteem and esteem from others.

5. Need for self-actualisation: Once all other needs are satisfied the individual seeks self fulfilment and seeks realisation of his potential. This is related to a person’s self concept and perception of self into reality.

Maslow did not apply the hierarchy of needs to work motivation for almost twenty years[lxxxvii], however others popularised Maslow’s theories into management literature. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is taught in almost every business school in the world, and for a long time uncritically accepted. However, Maslow’s theory was developed in American society in the 1940’s and fails to explain issues why people deprived of lower needs turn to spirituality and devotion to religion[lxxxviii]. Research utilising Maslow’s theories has come up with inconclusive results[lxxxix]. Most importantly, Maslow’s theory failed to take account of the influence of culture on social needs in the workplace, which puts into question the theories relevance to the Malaysian work context.

Abraham Maslow

David McClelland was a Harvard University psychologist who is best known for his achievement model and work on power in organizations. McClelland with his co-researchers began looking in 1947 at all aspects of achievement. He developed a profile of the characteristics of a high achiever[xc];

1. A high achiever will take moderate risks,

2. High achievers have a desire for immediate feedback on how they are progressing toward a goal. High achievers prefer to do things that give relatively quick results, such as sales jobs or management positions with measurable performance criteria, rather than something long-term with slow results. Professions like research and development or a teaching profession would be frustrating to them.

3. High achievers find accomplishment satisfying in itself, they don’t necessary want the accompanying rewards. Their attitude towards money is not as an ends, but look at money as a form of feedback or measurement of how they are performing. Given the choice of a non-challenging job with a high reward or a challenging job with a low reward, on the whole, the high achiever would select the latter.

4. High achievers are preoccupied with the task, once they have set their goals, they will pursue them until the goals are achieved. They cannot stand to leave a job half done and not satisfied until they have made full effort. This often reflects in their outward personalities, which can have a negative effect on others. Often high achievers have the characteristic of being a loner. They tend to be very realistic and don’t allow others to get in their way. Typically these people are good salespeople, but not good managers. Similarly they are good entrepreneurs, but not good at managing an ongoing enterprise.

Approximately 10% of the population could be considered high achievers and this can be seen from childhood[xci].

McClelland also researched a person’s needs for affiliation. He found that the need for affiliation or intimacy with a group plays an important role in motivation. There are various reasons behind the need for intimacy. Groups are perceived to provide a sense of security for individuals where there is some uncertainty, or fear of something external to the individual and group. Groups also provide individuals with a cognitive clarity (sense of how to interpret events around them) and a way to make a self evaluation and social comparison about the way they should dress, talk, think and act. Generally, women’s needs for intimacy are higher than men.

McClelland also researched a third motivator, status, power and prestige. Many people are status seekers in their careers, who desire material status symbols like good clothes, big houses, expensive cars, etc. This infers in their self-perception of higher in a social hierarchy than others. Social status can also be achieved through membership of a family, personal qualities, academic achievements, material processions and authority and power through career position. Status-determining factors may differ from culture to culture and will depend on cultural roles and values. McClellend stated that the drive for status for some people is very high and it seems to start developing at an early age. The need for status and power is a need to have an effect on others and a need of control over their lives and work. Associated with these needs is the likelihood that such people will also be susceptible to stress and anxiety and vulnerable to aliments and diseases, like high blood pressure[xcii], caused by a sense of lack of control over their lives and work[xciii]. The power need in men and women is perceived differently and will behave differently by this need motivation.

McClelland stated that each person has all three needs to different extents within them, which influence their behaviour. However one need will dominate as a rationale and motivator for their behaviour at any given time.

The psychoanalytic influence of Freud and Klein had led to beliefs that achievement motives are only developed in childhood and once developed, nothing much can be done to change them. McClelland went on to conduct courses on developing a need for high achievement in individuals, as he believed this could be learned and conditioned. He conducted these classes all around the world (including Asia) among both groups of company executives, which produced very positive results, measured by improvements in income levels after the course. The achievement-motivation course also worked on producing new entrepreneurs in India and indicated that this sort of training could have benefit in assisting disadvantaged groups as well as corporate groups in developing their achievement-motivation[xciv]. The achievement-motivation course had four goals[xcv];

1. To teach participants how to think, talk and act like a person who is a high achiever,

2. To stimulate participants to set higher, but more carefully planned goals over the next two years,

3. To give participants more knowledge about themselves, and

4. To create group bonding from learning about each others hopes and fears, successes and failures, and from going through emotional experiences together, in a retreat setting.

McClelland extended his research to societies and hypothesized that in a country whose populace showed a high achievement factor, the country will experience high economic growth and prosperity, whereas a society consisting of low achievers will economically decline and eventually collapse[xcvi].

David McClelland’s work was similar to Maslow’s and had many parallels with other behaviourist psychologists at the time. McClelland also showed that need achievement and motivation could be learned and that self esteem and mutual group reinforcement and support was very important to this. Contemporary behaviourial research into entrepreneurship heavily cites McClelland’s work on the issues of why people become entrepreneurs.

David McClelland

Frederick Herzberg was another clinical psychologist with a passionate humanity, influenced by his wartime experiences. Herzberg basically believed that tasks performed by people at work has an influence over psychological growth and people were satisfied and mentally to the extent that work provided opportunities for achievement, recognition, challenge, personal advancement and learning[xcvii]. Herzberg extended the work of Maslow and undertook a study of accountants and engineers in Pittsburgh, from which he developed his Two Factor Theory. Herzberg identified certain factors relating to the work task that he called hygiene factors, which reduce a persons dissatisfaction with their work situation and motivators which result in job satisfaction. Herzberg postulated that hygiene factors must be satisfied before motivators have a positive effect on the employee’s commitment to the company and productivity. A description of the hygiene factors and motivators is below[xcviii];

Hygiene Factors

Salary

Status

Security

Working conditions

Fringe benefits

Company policies, i.e., leave etc.

Interpersonal relations in the workplace

Motivators

Meaningful work

Challenging work

Recognition for accomplishment

Feeling of achievement

Increased responsibility

Opportunities for growth and advancement

The job itself.

Herzberg;s two factor theory, like Maslow’s became a standard textbook and business school theory and was widely accepted by practitioners in the 1960’s. Herzberg’s work was the focus of numerous studies in subsequent years, which gave a number of criticisms of the two factor theory[xcix]. However it is widely recognised today that Herzberg’s work was still an intermediate explanation of job satisfaction and it influenced much further research into the area of job satisfaction and job enrichment.

Frederick Herzberg

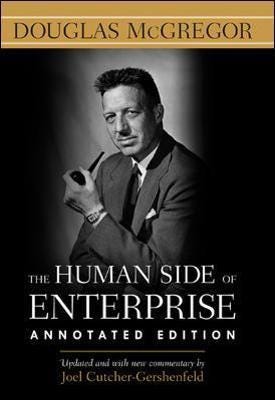

American psychologist Douglas Macgregor developed a theory on two different views of people and their implications for management. Theory X was an assumption by managers that people were basically lazy, extrinsically motivated, undisciplined, want job security but no responsibility in their jobs. In contrast Theory Y was an assumption by managers that people do not inherently dislike work, are extrinsically motivated, are capable of self-control and seek responsibility[c]. Most managers took the Theory X view and thus it could be explained why they were reluctant to delegate responsibility, etc. Adopting a Theory Y approach is a more innovative way of managing, where responsibility, much looser control and much more goal-orientated approaches can be undertaken. Macgregor had the same humanist philosophies as Maslow and Herzberg, believing that human motivation was complex and the organisation could benefit from the differences of individuals, thus Theory Y management was the preferred option to go.

Macgregor’s work still has great influence on management today and is still standard in most textbooks and business schools. Macgregor’s ideas probably brought about the development of the human resources manager as an extension of Theory Y management in the organisation, where training systems were developed to promote this style of management. Macgregor was working on Theory Z, which aimed to bring together the needs and aspirations of the individual and organisation, when he died in 1964. William Ouchi took over the idea and examined the lessons US companies could learn from their Japanese counterparts, such as consensus decision making, lifetime employment, slow promotion and planned succession, concern for employees including social life, and commitment to the firm[ci]. Macgregor’s work was also to influence the writings of Kanter, Bennis and Peters, which we will be looking at soon.

Dr. Bruce Tuckman developed his group behavioural modal in 1965. Tuckman’s model explains how a group forms and develops from the interpersonal relationship point of view. Tuckman postulates there are four stages in group development;

1. Forming: this point the individuals roles are still ambiguous and unclear and there is a high dependence of the leader for guidance and direction. Members of the group ask a lot of questions about purpose and external relationships and the leader is the dominant person in a still informal environment. However individual members maybe testing the tolerance of the group and leader.

2. Storming: During this stage decisions are not easy to make as members are developing their positions in relation to each other and the leader within the group. Challenges to the leader may come at this point as cliques and factions form. The group is beginning to have a purpose and objectives, but still with some uncertainty as direction and focus is distracted by relationships and emotions, often in the form of a power struggle. The group forms methods to solve these problems through compromises or other mechanisms.

3. Norming: During this time there is usually consensus within the group, which responds to the facilitation by the leader. People accept their role and responsibilities and decisions start being made. Commitment and unity is now strong and the group may engage in social activities. The team has decided its process, working styles and rules. The leader has earned some respect from the group.

4. Performing: The team clearly understands what it is doing and the reasons for doing so. This vision is shared and the group has momentum without much interdiction by the leader. There is focus on goal achieving and the team makes most decisions against the objective of meeting the goals set. Disagreements are solved within the group amicably and any necessary changes in structure and processes made when seen fit. Team members have developed a sense of comradely and work by delegation.

Tuckman’s model was one of the first propositions about group dynamics and leadership in the group environment and certainly had influence of the ways of thinking about an organization as a culture and on future leadership models postulated by Tannenbaum and Schmidt. Group dynamics are an important part of management studies at business schools because of its influence on leadership, productivity, satisfaction, efficiency and innovation. Unfortunately, Tuckman’s contribution has all but disappeared from the textbooks, with his ideas absorbed into more holistic models of organization.

Bruce Tuckman

Henry Mintzberg in the early 1970’s dispelled the myths of management by analysing what a manager really does and cast these activities into various roles, which could be grouped into three categories[cii];

Interpersonal role: as a figurehead, leader and decision maker,

Informational role: as a monitor, disseminator, spokesperson and,

Decision maker: as an entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocatur and negotiator.

Mintzberg found that what work people do in different positions of the hierarchy and functional level was in essence very similar in role and characteristics, i.e., all were a figurehead for the department or section, leader, liaison person, monitor and disseminator, spokesperson, entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocatur and negotiator. In the jobs managers do there is both a routine and non-routine component. Managers need to be both generalists and specialists and usually work on information supplied verbally. Management is more an art than science basically relying on intuitive and non-explicit processes. Mintzberg found that managers change their focus from subject to subject, problem to problem and unable to concentrate on any subject for any length of time without an interruption. Mintzberg’s studies and surveys proved that management is really a complex split focus task, which challenged notions prevailing at the time.

The combined works of Mayo, Maslow, Herzberg, Macgregor and Tuckman, among many others in the other paradigms of strategy, organisation, marketing and production, changed the way management was viewed. This propelled management schools to the forefront, where the Master of Business Administration (MBA) came into it’s own as a perceived necessity for rising management to take. This gave rise to the birth of the professional manager, for the first time graduates not necessarily linked to disciplines like engineering or accountancy, who upon graduation began filling the ranks of lower and middle management in organisations around the world. Previously, people in organisations could work their way up from the bottom, i.e., in a bank start as a teller and one day rise to the level of manager. Management schools put a stop to this and in many ways stopped the upward mobility of people in organisations, based on experience and loyalty. The 1980’s came with the perception of the ‘gung ho’ manager, which was about to be encouraged even further with the flood of new ideas in management and number of business books on bestseller lists.

Tom Peters and Robert Waterman were employees at Mckinsey, one of the premier management consulting firms in the United States. They carried out research to identify common characteristics of successful companies, based on a selection criteria of six financial measurements. Their basic conclusion was that excellent companies exercised commonsense and kept very close to the business basics[ciii]. Peters and Waterman called in two academics Richard Pascale and Anthony Athos to assist them make sense of the data and select the important characteristics of success. Strategy, structure and systems had between determined and Pascale suggested style and shared values to complete five components of the Seven S Framework. After some weeks of discussion skills was added to the framework to make up six components. The seventh was decided upon as sequencing, but later replaced with staff. Peters was also proposing adding power, but this didn’t eventuate[civ].

The Seven S Framework was featured in Peters and Waterman’s book In Search of Excellence, published in 1982. The book was far from being an academic piece of literature and written in a popularist format, easy to read with lots of stories to get the messages across. Even though the Seven S Framework was sharply criticised for making organisational behaviour simplistic, akin to an advertising agency developing slogans and that many of the excellent companies described in the book are not performing well now[cv], the book had many relevant messages, in a chapter by chapter format, which came to corporate America at the right time[cvi];

A bias for action, active decision making - 'getting on with it'.

Close to the customer - learning from the people served by the business.

Autonomy and entrepreneurship - fostering innovation and nurturing 'champions'.

Productivity through people - treating rank and file employees as a source of quality.

Hands-on, value-driven - management philosophy that guides everyday practice - management showing its commitment.

Stick to the knitting - stay with the business that you know.

Simple form, lean staff - some of the best companies have minimal HQ staff.

Simultaneous loose-tight properties - autonomy in shop-floor activities plus centralised values.

Given the criticisms, In Search of Excellence is one of the all time best selling management books of all time and Tom Peters is the most highly demanded speaker in the management circuit. Peters in his way of putting things has managed to inspire many and bring up the ‘management culture phenomenon’. However, although most managers at the time had a copy on the bookcase behind their desk, actually how many read it and were able to implement any of the ideas is another thing. Tom Peters as an influence on management thought continued with his books A Passion for Excellence, Thriving on Chaos, Liberation Management, The Tom Peters Seminar, The Pursuit of Wow! and The circle of Innovation. Bestsellers that followed the ‘strategies for success’ format more than a decade later include Jerry Porras and James Collins’, Built to Last and Jeffrey Pfeffer’s The Human Equation.

Roseabeth Moss Kanter

Roseabeth Moss Kanter is a professor at Harvard Business School and also a consultant and lecturer travelling around the world with her message to audiences. Although she does not take the evangelistic approach of Tom Peters, her work is rigorous but at the same time popularist, and appealing to her audiences. Kanter of concerned with integration between the individual and the corporation, influenced by Mayo and Macgregor’s works and a pragmatic idealist viewpoint, viewing organisations as micro-societies somewhat akin to the cultural frame like Schein, Kilmann and Deal and Kennedy. She has also drawn from Hofstede and Trompenaars in her later works.

Her first book Men and Women of the Corporation published in 1977, Kanter examined bureaucratic organisation and hypothesised that managers are emersed within a restrictive environment and espoused new types of organisations that would empower the manager. The Change Masters in 1984 continued with her theme of empowerment in organisations, where unwillingness and even fear prevented corporations from disengaging from their anchors of the past and creating more innovative and dynamic environments.

Kanter’s third book When Giants Learn to Dance in 1989 encapsulated the message of transformation to a new type of corporation, necessary because of the dynamic environments and forces of globalisation firms now find themselves in. Kanter espoused that companies must take a re-look at their core competencies, expand through strategic alliances and utilise outsourcing for specialisation and peripheral activities. Proof of this is the growing service industries around the world. As companies become more globalised cross, cultural management will become one of the biggest management issues facing the corporation.

Kanter said that successful corporations will break away from their structures where process will dominate, creating a much more flexible organisation where resources can be reconfigured in the best ways to meet the challenges it faces. Communication will flow where necessary rather than through formal channels of a hierarchy. Kanter calls this the post entrepreneurial firm which will be created by commitment from management at the top changing employees values, change of structure and education within the middles management and freeing up lower management to participate in creating ideas for new products, services and markets, new processes and ways to get closer to their customers. Kanter identifies seven skills managers will have to develop to transform themselves from just managers to business athletes[cvii];

Learning to operate without the support of hierarchy,

Knowing how to compete in a way that enhances rather than destroys cooperation,

Operating with the highest ethic standards,

Displaying humility,

Developing a focus on process,

Being multi-disciplinary, and

Gaining satisfaction from results.

Kanter’s works are popular because they show what a corporation could be and demonstrates pragmatic ways on how to achieve this, in an era where corporations are pre-occupied with down-sizing, cost-cutting and eliminating middle management. As with Tom Peters In Search of Excellence, how many of these ideas are implemented is questionable, but many corporation managers have become empathetic with the ideas, values and strategic issues they face in the near future.

The corporate world in the 1980’s had grown so powerful, many corporations were larger than some national economies and seemed to operate without the scrutiny of anybody. Decisions made by corporations could devastate local economies and the Union Carbide accident in Bhopal, India in 1984, showed how unaccountable corporations could be. Union Carbides actions of stripping the assets of the company and distributing the proceeds to shareholders[cviii], rather than attempting to assist and compensate the victims, led to disillusionment with corporate management. Corporations and managers seemed to have unlimited power and ruthlessly pursued the goal of profits without accountability to anyone[cix]. A perception prevailed that ‘making money and greed was good’ epitomised by the character Gordon Ghekko in the blockbuster film, Wall Street. The brave new world of the corporation was here, but it had come with a spiritual vacuum.

Stephen Covey

Enter Stephen Covey, a devout practicing member of The Church of Latter-Day Saints, evangelistically preaches personal development, fulfilment and spirituality within the context of the organisation. Covey’s first book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective people set a standard of highly ethical and humanistic principals that all individuals should strive for in business[cx];

Be proactive as this will develop the ability to control one’s environment, rather than be controlled by it, as is generally the case.

Begin tasks with the end result in mind, avoid distractions and concentrate only on relevant activities, which will make you much more productive,

Organise correctly and undertake the most important tasks first in a step by step approach,

Look for win-win strategies so that all benefit,

Listen to people first and understand them before you try to make them understand you, which will assist in maintaining positive relationships with people,

Look to develop synergy between people which will develop a better outcome, greater than what individuals can achieve working by themselves, and

Continually seek self-renewal, spiritually, mentally, emotionally, socially and physically.

Covey’s book sold over 15 million copies and launched him on a career of consulting to many of the top Fortune 500 companies. Covey built a training and consultancy company which has over 12,000 direct facilitators with curriculum materials translated into numerous languages. Covey’s organisation has also developed pilot programs with cities wishing to become principal centred communities. Covey’s set of life rules is not without their critics who claim his ideals are too idealistic and difficult to implement as well as being seen as a quick fix approach. However, this does not detract from the extremely large following of devotees to Covey’s methods growing around the world. There are similarities with Peter Drucker, Dale Carnegie and David Allen in the approach. Dale Carnegie’s work is also on the rise again in popularity and consequently, corporations are taking notice of the importance of employee personal growth within the corporate environment.

The ideas of empowerment continued through the 1990’s with observable changes in the ways corporations set up their internal structures. Ratios between employees and supervisors decreased dramatically and support staff in offices also decreased dramatically with executives doing their own typing, photocopying, etc. Secretaries were replaced with assistants who became involved in the managerial work itself. One cannot forget that there were other factors like the development of information technology and need of firms to cost cut staff to cope with the downturns and recession in the economy during the early 1990’s. Corporations with information technology could, where before they could not decentralise decision making and operate with less middle management. With some scepticism, one could come to the conclusion that the concept of empowerment, an espoused word in corporate vocabularies, was either misunderstood or mis-practiced, intentionally or unintentionally. However, continuing along the lines of Argyris, McGregor, Kanter and others, Quinn Mills and Bruce Friesen espoused empowerment as something far beyond management delegation but as a management style[cxi]. Although there is more than fifty years of management thinking supporting the philosophy of empowerment, it still remains to be seen whether it is a fad or substantial change in the way management does things.

Companies have always sort to measure their performance and realised the limitations of relying on just financial reports. For years there has been debate by the accounting profession about the need for wider methods of measuring performance. Corporate scandals during the 1990’s also indicated a need for board of directors to have some sort of measure to show the overall wellbeing of the corporation[cxii]. Management also realised that it was not the formulation of strategy that was difficult, but its implementation[cxiii], so some sort of measure of implementation success was required. Finally, management also needed a technique that would also garner commitment from employees for the company’s goals and mission[cxiv].

Robert Kaplan, an accounting professor at Harvard and David Norton, a consultant, developed the concept of the balanced scorecard which was a way of measuring important variables across the organisation, so data could be viewed in a holistic way. Cause and effect relationships could be examined and management could analyse the effect of changing something one area on all others areas of the business. The balanced scorecard focused on four main areas[cxv] of the business;

From the Customers Perspective – how they see the organisation and what has to be done to remain a valued supplier?

From the Internal Perspective – what internal processes must be improved if objectives in relation to customers and other stakeholders are going to be achieved?, and

Innovation and Improvement – how can the company continue to improve and create value in the future? What measures are required?

Financial Perspective – how does the company look to the shareholders?

One of the keys to developing a successful scorecard is selecting the correct indicators and ensuring they are complementary and not duplicating or overlapping[cxvi]. Included in the indicators must be lead and lag indicators which show current position and indicate with strategy, where the firm can travel. The balanced scorecard proved too popular to be called a fad and use of it has extended into government and non-profit institution. The balanced scorecard approach has also become a large consulting industry with computer software systems available.

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

References:

[i] Hafez, K., (2000), ‘The West and Islam in the Mass Media: Cornerstones for a New International Culture of Communication in the 21st Century’ Discussion Paper C61, Centre for European Integration Studies, Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms-Universatät, Bonn.

[ii] Policy Bulletin, (2005), The US Media and the Muslim World, Atlanta, GA, The Stanley Foundation, January 13th. (Accessed at www.stanleyfoundation.org, 19th December 2006).

[iii] Hassan, R., (2006), ‘Islamic world faces intellectual stagnation’, Asia News Network, http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2006/11/04/opinion/opinion_30018026.php, (accessed 6th November 2006).

[iv] Shams, R., (2004), ‘A Critical Assessment of Islamic Economics’, HWWA Discussion Paper 281, Hamburg Institute of International Economics, Hamburg, Germany.

[v] Chapra, M., U., (1990), Islam and the Economic Challenge, Leicester, UK., Islamic Foundation and Virginia, USA., The International Institute of Islamic Thought.

[vii] Al-Qur’an (3:164)

[viii] Koya, P.K., (Editor), (1996), Hadĭth ans Sunnah: Ideals and Realities, Kuala Lumpur, Islamic book Trust, Introduction xiii.

[ix] Hassan, M., A., (1992), The Tawhidic Approach in Management and Public Administration: Concepts, Principals and an Alternative Model, Kuala Lumpur, National Institute of Public Management, pp. 6-7.

[x] Al-Qur’an (51:56)

[xi]Al-Qur’an (30:30)

[xii] Al-Qur’an (4:28))

[xiii] Al-Qur’an (20:115)

[xiv] Al-Qur’an (102:1-2)

[xv] Al-Qur’an (33:72)

[xvi] Al-Qur’an (17:11)

[xvii] Al-Qur’an (17:100)

[xviii] Al-Qur’an (17:67)

[xix] Al-Qur’an (18:54)

[xx] Al-Qur’an (70:19-20)

[xxi] Al-Qur’an (4:128)

[xxii] Beekum, R., I., (1996), Islamic Business Ethics, Herndon, VA., International Institute of Islamic Thought.

[xxiii] Mohsin, M., (1995), Economics of Small Business in Islam, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Visiting Scholar Research Series No. 2., Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Development Bank.

[xxiv] Mehar, A., (2004), From Knowledge Creation to Economic Development: Missing Links in the Muslim World, Munich, Germany, MRPA Paper No. 358, http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/358/, (Accessed 19th December, 2006).

[xxv] Kahf, M., (2003), Sustainable Development in the Muslim Countries, , Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, IDB Prize Winners’ Lecture Series, Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Development Bank

[xxvi] Beal, T., (2006), The Global Islamic Economy: A rough estimate of the position of Islamic peoples

in the global economy, paper presented to the Seminar on Islam And The Global Economy

Malaysian And Nz Perspectives, Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday 13th June. (http://www.vuw.ac.nz/~caplabtb/beal.html, Accessed 19th December 2006).

[xxvii] Al-Qur’an (35:29), (26:207), (17:82).

[xxviii] Al-Qur’an (2:164)

[xxix] Al-Qur’an (5:3)

[xxx] Al-Qur’an (2:168)

[xxxi] Al-Qur’an (14:32-34)

[xxxii] Al-Qur’an (24:37)

[xxxiii] Siddiqi, M., N., (2005), ‘Tawhid: The Concept and Process’, in Syed Agil, S., O. and Ghazali, A., (Eds.), Readings in the Concept and Methodology of Islamic Economics, Kuala Lumpur, CERT Publications, P.1.

[xxxiv] Al-Qur’an (2:170), (43:22-24), (7:28-29).

[xxxv] Al-Qur’an (22:77)

[xxxvi] Al-Qur’an (2:275)

[xxxvii] Al-Qur’an (17:36)

[xxxviii] Al-Qur’an (92:4), (29:69).

[xxxix] Hassan, M., A., (1992), op. cit., P. 24.

[xl] Al-Qur’an (31:20)

[xli] Al-Qur’an (35:28)

[xlii] Al-Qur’an (51:56)

[xliii] Al-Qur’an (2:21)

[xliv] Ismail, A., H., (1992), ‘Bank Islam Malaysia Bhd.: Principals and Operations’, in Sheikh Abod, S., G., Syed Agil, S., O., and Ghazali, A., (Eds.), An Introduction to Islamic Finance, Kuala Lumpur, Quill Publishers, P. 258.

[xlv] Doi, I., A., R., (1981), Non-Muslims Under Syar’iah, Lahore, Kazi Publications, P.4.

[xlvi] Al-Buraey, M., A., (1988), Administrative Development: An Islamic Perspective, London, Kegan Paul International, P. 145.

[xlvii] Chaudry, M., S., (2006), Social and Moral Code of Islam, Batu Caves, Selangor, Malaysia, Masterpiece Publications, P. 15.

[xlviii] Halal-Haram Guide (2006), Penang, Consumers Association of Penang, P. 17.

[xlix] Amin, M., (1965), Wisdom of the Prophet Muhammad, Lahore, Pakistan, Sh. Muhammad Ashraf.

[l] Abdullah, A., and Huda, N., (2006), ‘Nutrition Security in Muslim Countries: The Drive Towards a Healthy Ummah’ in Saifuddeen, S., M., Mohd. Salleh, S., and Sobian, A., Food and Technological Progress: An Islamic Perspective, Kuala Lumpur, MPH Publishing, P. 173.

[li] Al-Qur’an (7:58)

[lii] Al-Qur’an (5:5), (2:168)

[liii] Al-Qur’an (2:198)

[liv] Al-Qur’an (7:31)

[lv] Al-Qur’an (25:67)

[lvi] Al-Qur’an (22:77)

[lvii] Al-Qur’an (3:1-2), (4:125)

[lviii] Al-Qur’an (6:132), (16:97), (16:93)

[lix] Al-Qur’an (90:8-10)

[lx] Al-Qur’an (30:41), (103:1-3)

[lxi] Al-Qur’an (33:72)

[lxii] Al-Qur’an (2:169)

[lxiii] Al-Qur’an (33:72)

[lxiv] Hassan, M., A., (1992), op. cit., pp. 66-68.

[lxv] Al-Qur’an (42:36-40)

[lxvi] Al-Qur’an (3:159)

[lxvii] Lapidus, M., (1984), ‘The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam’, in Metcalf, B., D., (Ed.), Moral Conduct and Authority, Berkeley, Los Angeles, University of California Press, P. 39.

[lxviii] Albers, H., H., (1974), Principals of Management, 4th Edition, New York, John Wiley & Sons.

[lxix] Gulick, L., (1937), ‘Notes on the Theory of Organization’, in Gulick, L. and Urwick, L., (Eds.), Papers on the Science of Administration, New York, Institute of Public Administration.

[lxx] Terry, G., (1972), Principals of Management, 6th Ed., Homewood, Ill., Richard D. Irwin.

[lxxi] Koontz, H. and O’Donnell, C., (1976), Management, 6th Ed., New York, McGraw-Hill.

[lxxii] Urwick, L., (1943), The Elements of Administration, New York, Harper & Brothers.

[lxxiii] Fayol, H., translated by Storrs, C., (1949), General and Industrial Management, London, Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd.

[lxxiv] Luthans, F., (1976), Introduction to Management: A Contingency Theory Approach, New York, McGraw-Hill, P. 59.

[lxxv] Follet, M., P., (1924), Creative Experience, London, Longman.

[lxxvi] Follet, M., P., (1942), ‘Constructive Conflict’, in Metcalf, H., C. and Urwick, L., (Eds.), Dynamic Administration: The Collected Papers of Mary Parker Follet, New York, Harper & Row.,

[lxxvii] Strauss, G., (1986), ‘Workers’ Participation in the United States’, in Davis, E. and Lansbury, R., (Eds.), Democracy and Control in the Workplace, Melbourne, Longman Cheshire.

[lxxviii] Sieff, L., (1990), On Management: Marks & Spencer Way, Wiedenfeld & Nicolson.

[lxxix] Cray, E., (1978), Levi’s, Boston, Houghton Mifflin.

[lxxx] Mayo, E., (1945), The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilization, Boston, Harvard University Graduate School of Business Administration, Division of Research.

[lxxxi] Mayo, E., (1947), The Political Problems of an Industrial Civilization, Boston, Harvard University Graduate School of Business Administration, Division of Research.

[lxxxii] O’Brien, G., (1986), Psychology of Work and Unemployment, Psychology and Productivity at Work Series, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons.

[lxxxiii] Murray, H., A., (1938), Explorations in Personality, New York, Oxford University Press.

[lxxxiv] Morgan, C., D. and Murray, H., A., (1935), ‘A method of investigating fantasies’, Archives of Neurological Psychiatry, 34, pp. 289-306.

[lxxxv] Allen, B., P., (2003), Personality Theories: Development, Growth and Diversity , 4th Ed., Boston, Pearson Education.

[lxxxvi] Maslow, A., H., (1943), ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’, Psychological Review, July, pp. 370-396.

[lxxxvii] Maslow, A., H., (1965), Eupsychian Management, Homewood, Ill., Richar D. Irwin and The Dorsey Press.

[lxxxviii] Wahba, M., A. and Birdwell, L., G., (1973), ‘Maslow Reconsidered: A Review of Research on the Need Hierarchy Theory’, Proceedings of the Academy of Management, pp. 512-520.

[lxxxix] Hall, D., T. and Nougaim, K., E., (1968), ‘An Examination of Maslow’s Need Hierarchy in an Organizational Setting’, Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance, Feb., pp. 12-35.

[xc] McClelland, D., C., (1961), The Achievement Society, Princeton, N.J., D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc.

[xci] McClelland, D., C., (1961), opt. cit., pp. 297-304.

[xcii] McClelland, D., C., (1979), ‘Inhibited power motivation and high blood pressure in men’, Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 88., pp. 182-190.

[xciii] McClelland, D., C., (1982), ‘The Need for Power, Sympathetic Activation, and Illness’, Motivation and Emotion, 6., pp. 31-41.

[xciv] McClelland, D., C., (1965), ‘Achievement Motivation Can Be Developed’, Harvard Business Review, Nov.-Dec., p. 20.

[xcv] McClelland, D., C., (1966), ‘That Urge to Achieve’, Think, Nov.-Dec., P.22.

[xcvi] McClelland, D., C., (1961), opt. cit.

[xcvii] Herzberg, F., (1966), Man and the Nature of Work, Cleveland, World Press.

[xcviii] Herzberg, F., Mausner, B. and Snydermann, B., B. (1959), The Motivation to Work, 2nd. Ed., New York, John Wiley & Sons.

[xcix] Vroom, V., H., (1964), Work and Motivation, New York, John Wiley & Sons.

[c] Macgregor, D., (1960), The Human Side of Enterprise, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[ci] Ouchi, W., G., (1981), Theory Z: What American Industry can Learn from the Japanese, Reading, Mass., Addison-Wesley.

[cii] Mintzberg, H., (1973), The Nature of Managerial Work, New York, Harper & Row.

[ciii] Crainer, S., (1998), Key Management Ideas, 3rd Edition, London, Financial Times.

[civ] Ibid.

[cv] Ibid.

[cvi] Peters, T. and Waterman, R., (1982), In Search of Excellence, New York, Harper & Row.

[cvii] Kanter, R., M., (1989), When Giants Learn to Dance, New York, Simon & Schuster.

[cviii] Hawken, P., (1994), The Ecology of Commerce, New York, Harper Business.

[cix] Kao, R., W., K., Kao, R., R. and Jing, Y., ( 2006), An Entrepreneurial Approach to Corporate Management, 2nd Ed., Singapore, Pearson Education.

[cx] Covey, S., R., (1990), Principal Centred Leadership, New York, Free Press.

[cxi] Mills, Q., D. and Friesen, B., (1995), ‘Empowerment’, in Financial Times Handbook of Management, London, Financial Times/Pitman.

[cxii] Lorsch, J., W., (2002), ‘Smelling Smoke: Whay Boards of Directors Need the Balanced Scorecard’, Balanced Scorecard Report, Sept.-Oct., P. 9.

[cxiii] Galpin, T., J., (1997), Making Strategy Work, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

[cxiv] Drucker, P., F., (1999), Management Challenges for the 21st Century, New York, Harper and Collins.

[cxv] Kaplan, R., S., and Norton, D., P., (1996), The Balanced Scorecard, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

[cxvi] Gane, R., Haigh, N. and O’Brien, A., (2002), ‘A Balanced Scoreboard’, Manufacturing Engineer, June, P. 123.