The evolution and influence of thinking in management Part 7: Creativity/Cognitive Thought

An unpublished series of management ideas

The seventh and final part part covers ideas and practices which have shaped the way we think about creativity and cognition today.

Creativity/Cognitive Thought

Creativity and cognitive thought is where substantial breakthroughs have been made over the last century. We have reviewed economic, production, strategic, organisational, managerial and leadership thought and see that learning, creativity and innovation have become a major part of those paradigms or disciplines. We can think of strategy as creativity, the way a firm develops an idea into something that can be executed. If we take the Darwinian view of an organisation that it must evolve and change in order to survive, creativity and learning is paramount to this. The transformation of Nokia from a logging company to a mobile phone manufacturer, Bunnings similarly a timber company in Tasmania, now the market leader in the retail and wholesale hardware industry with outlets all over Australia and here in Malaysia the transformation of Singer from a sowing machine manufacturer to a company with a chain of specialised household goods outlets, tends to support this view. Vijay Arora and Lorenzo Faraone strongly argue that even technical disciplines like engineering will be primarily orientated towards creative thinking and problem solving with the need of strong communication and leadership skills as we head towards what they call knowledge engineering[1]. This will shift the paradigm of the engineer and other technically orientated disciplines completely.

Vijay Arora

Ivan Pavlov was a Russian physiologist born in 1849. He founded the Institute of Experimental Medicine in 1890, where his primary interest was digestion. Early in the 20th century Pavlov commenced experiments on the conditional response of dogs. Pavlov presented a piece of meat to the dogs, ringing a bell each time. After a period of time, he rang the bell without presenting any meat and the dogs and found the dogs still salivated in anticipation of the meat. This experiment showed that conditioned response (salivation) could be achieved from a conditioned stimulus (the bell), hence the name conditional learning.

By continually repeating the conditioned Stimulus, the conditioned response weakened, and then eventually to disappeared, which Pavlov termed extinction. Surprisingly though, a after a day or two, when the conditioned Stimulus (sound) was recommenced, the dog produced the Conditioned Response (salivation) again, which is called spontaneous recovery. This showed that conditioned behaviours can become very deeply embedded and well established.

Ivan Pavlov

Pavlov’s work began the behaviourists school of psychology thinking, where many felt it was more advantageous to deal with observable behaviours rather than the elusive mind[2]. Pavlov’s classical conditioning experiment for this reason was probably the single most famous study ever conducted in the behavioural sciences[3]. Burrhus Frederic Skinner, one of the grandfathers of modern psychology felt that Pavlov’s conditional learning only showed reflexive behaviours and involuntary responses and thus represented only a very small aspect of human learning[4]. George Kelly, another forefather of modern psychology said “there is no reason we should not be grateful even though we are not quite sure what it was he demonstrated”[5]. Pavlov’s experiments brought up more questions than it answered, which we don’t know much about[6];

1. Is learning a sudden or gradual process?

2. When learning occurs, what exately are we learning?

3. How many kinds of learning are there?

4. Is learning without awareness possible?

These questions are relevant to creativity and cognitive processes and require numerous other questions to be asked before we can attempt to answer them.

Newman, Summer and Warren in 1972 made an attempt to define some general guidelines to stimulate creativity within an organisation[7];

1. Recognise psychological barriers – primarily psychological and cultural barriers,

2. Try changing attributes of the problem by focusing on other attributes,

3. Be alert for serendipity, and

4. Recognise that computers have the ability to supplement the human mind in particular stages of the creative process.

At the time, this was about the only advice around to assist managers make creative decisions.

Frederic Skinner

Scientists looked at ways individuals and organisms learned, thought and developed strategy. Polva in 1945 saw that individuals and groups made decisions based on only partial data and adjusted strategies based on continual evaluation of the environment. Thus decision making was a merging of logic, philosophy and psychology[8]. John Hutchinson saw heuristics as a blend between the systems and behavioural approach to decision making as consideration of strategy would take both major variables and people into account, where there is a need to make non-rational decisions to find preferable solutions and avoid frustrations[9]. Stafford Beer saw heuristics as a method of behaving which will lead towards a goal which cannot be precisely specified because we do not know what it actually is. Beer went on to say that we tend to live our lives by heuristics, and try to control our lives by algorithims (rules)[10]. Our lives are controlled by goals, yet our goals are in the future, which is uncertain and influenced by the turbulence of the environment.

Theoretically, if we give a computer and algorithm which operates a heuristic, and let it develop a strategy, the computer will be able to take account of all experiences we as humans may forget and thus create superior strategies than humans can[11]. Thus computers in games like chess will be superior to humans. These ideas were developed into 4GL computer languages in the 1980’s and used in business strategy games at the time. These attempts didn’t achieve much significance in the area of management, except for computerized production planning models in industry, employing heuristics in their programs. However the heuristic paradigm is a good way to look at how a firm develops strategy and this understanding has potential applications in the development of manufacturing facilities for new products[12], etc. Recently, researchers have identified that heuristic biases in cognitive processes could be an explanation of why some individuals spot opportunities and others do not[13], which is very important aspect of strategy development.

Brainstorming was developed by Alex Osborn in the early 1950’s as a tool in advertising for groups to generate a large number of ideas without consideration for their merits. Osborn describes brainstorming as the brain storming over creative problems in a commando fashion which each stormer attacking the same objective[14]. To develop maximum creativity from the group, four rules must be strictly enforced and followed by all;

Critical judgement is not allowed,

Complete freedom is welcomed,

Quantity over quality is wanted, and

Combination and improvement are sought.

Alex Osborn

Other specific aspects that will enhance effectiveness are a) sessions should be limited to around one hour, b) the problem shouldn’t be revealed before the session, c) the problem should be clearly stated and not too broad, and d) if a product is being discussed actual samples should be present[15]. Brainstorming assists decision makers think of unexpected and potentially useful strategies for settling a problem. However brainstorming can produce a number of shallow ideas, but it can increase the overall creativity of a group.

Brainstorming spread from advertising to all types of management decision making, however it is extremely limited for specific technical problems[16], and best for product, name or just to encourage creativity within a group. Recently brainstorming software has been developed[17] to assist groups and some companies like Australia Post have developed brainstorming labs where employees can hold sessions using the walls to scribble upon.

William Gordon developed a technique based on the assumption that creativity can be both described and taught to individuals and groups[18]. The Synetics technique involves two steps, 1) making the strange familiar and 2) making the familiar strange. The strange familiar phase is analytical in nature describing the problem. The familiar strange phase involves a conscious effort to look at the problem from a completely different viewpoint. Four types of analogy are used to stimulate creativity: personal, direct, symbolic and fantasy. These are considered the tools to initiate creative processes and by switching analogies to sustain the process. An example of the effectiveness of this method is the solution found for underwater construction by drawing analogies to shipworms, where they tunnel into wood and create a watertight compartment for themselves. Synetics differs from brainstorming where it is more suitable to looking at complex problems[19], as the example above displays. Synetics is not as well known as brainstorming but it has potentially greater application in decision making, especially in risk and uncertainty.

William Gordon

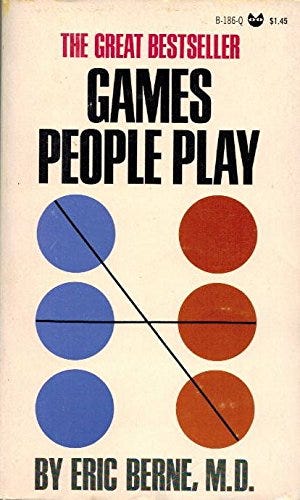

Game theory was originally developed by mathematicians to provide decision analysis based on the consideration of various options and anticipated reactions by competitors. It was also the base of the Program Evaluation Review Technique (PERT) and Critical Path Method (CPM), used in project management. Eric Berne developed an interpersonal relations model called transactional analysis (TA), which provided a framework for individuals to evaluate recurring sets of interpersonal transactions based on parent, adult and child frames[20]. His book Games People Play almost had a cult following at the time. This technique became extremely popular in the late 1960’s and is still used by many business schools as an interpersonal tool in organisational development. The concept was expanded to blend the original strategic aspects with the interpersonal aspects of TA to develop organisational simulations in potential business situations to play out scenarios such as what would be the effect on strategy, organisation and individual if a competitor lowered their price in the market, etc. Organisational simulations are now an important part of experiential learning in business schools and corporate training.

Edward de Bono is accredited to have pioneered the concept of lateral thinking. De Bono postulates that the brain is designed to make sense of the world by forming routine patterns of perception from incoming information. Information is channeled through our brain which dampens our creativity[21]. De Bono further postulates that once we understand this, we are able to break out of these patterns. He developed numerous concepts of deliberate thinking methods and creative thinking, teaching how to make thinking a conscious act rather than a reactive one. De Bono has developed a number of games to develop thinking skills. He is a prolific writer with over 65 books to his credit and set up the Cognitive Research Trust, which produces and promotes material based on his ideas. De Bono has been lecturing and consulting to governments and corporations for more than 30 years.

Edward de Bono

Herman Witkin had studied differences in peoples’ perceptual styles for 30 years and believed that personality can be revealed through differences in how people perceive the environment[22]. People make judgments on how they perceive the environment and Witkin found through a series of studies that people can perceive the environment in one of two ways. Witkin developed a test where people had to look at a complex picture with several hidden items in it. The goal was to find as many items in the picture. Some people viewing the picture would be bound up in the detail and not be able to see the items. These people are said to be field dependent. Others would be able to pick the items out and would be deemed field independent.

From further studies, Witkins found that field dependent students tended to favour social sciences and education, while field-independent students tended to favour the natural sciences, mathematics and engineering [23]. Field dependent people would rely more on social information and relate to others for opinions, look for social interaction and in general orientated towards people. Field independent people function with more autonomy and display a more detached and impersonal orientation to others. They are not very interested in others opinions, keep their distance from others and not very social[24]. Further studies after Witkins death found that field independent people tended to be less distracted from stimuli in the environment and able to concentrate on what they felt was necessary to focus on and also able to remember more details than field dependent people[25]. Other studies have shown that field independent people are able to pick out themes more easily in multi-media presentations than field dependent people[26]. Field dependence-independence shows that people also perceive and process information differently. Field independent people are good at selecting information in resource rich environments and block out what is not important, while feild dependent people tend to process information in chunks and are good at seeing connections between pieces of information[27].

Herman Witkin

The above studies have implications for the way people learn and how different people perceive environments, which has great implications in seeing opportunities and developing strategy. Even the nature of information and how it is formatted and presented will influence perceptions. Field dependence-independence also hints at how different people will display creativity skills. Field independent people are skillful at analyzing very complex situations and extracting what they see as relevant information from the stimuli of information, but will neglect social skills. Field dependent people will look more holistically and use their strong social skills to put things more in social contexts than field independent people[28]. These ideas haven’t been directly applied to strategic though in management, but could provide some very useful insights into how we perceive and construct our ideas.

Chris Argyris research began in the 1940’s when management was still seen as cut and dry in its approach to organization. Managers assumed they knew what to do, it was a matter of developing and organizational structure to carry out the requirements, tasks and specializations of the firm, orders would come down through the system and each person would be accountable and responsible for their jobs[29]. Managers believed they had all the necessary theories and methods available from the classical school of management thought for the smooth operation of the firm and were unwilling to change methods and practice because they had brought success previously and any change would threaten management prerogative and their right to authority[30]. This belief by managers prevents change in the firm as managers who return from seminars with new management ideas, introduce to staff without changing their underlying values and beliefs, leading to implementation failure because employees see no change in values and remain apathetic and indifferent[31].

Argyris, a philosophical humanist believed that current management philosophies ignored the complexity of the individual. Organisations operated with the assumption that employees had a psychological inability to be responsible and tended to treat them as children, inhibiting maturity in the organisation[32]. All organizations have an informal structure where individuals develop relationships to fulfill needs, alternative informal leaders have a great influence on behaviour, groups control member behaviour to satisfy their needs and because of the formal leader’s power to reward and punish, there is conflict between the formal and informal organisation[33]. This causes incongruities between what the organization demands of them and individuals basic needs, where they fail to obtain full expression of their personalities and remain dependent, rather than an independent person[34]. The behaviour resulting can lead to apathy, uninterested attitudes towards work, lower work standards, utilization of company resources for task avoidance and deep general work dissatisfaction[35].

Argyris found that in organizations, managers would espouse theories to employees about goals, assumptions, values and beliefs about behaviour expected of them, but act differently with another set of assumptions, values and beliefs, theories in action, that would be stronger in guiding employees behaviour than the espoused theories[36]. Espoused theories by management could range from autocratic to fully participative management, but almost always, managers theory in action would resemble what Argyris called a model I behaviour, built on the following basic assumptions; one must achieve one’s own goals as they see them, one must win rather than lose, one must minimize eliciting negative feelings in relationships and that one must be rational and minimize any emotions[37]. This leads to a behaviour that seeks control of others, leads to minimum confrontation on any emotionally charged issues, suppression of new ideas and solutions, bent on providing safety to members. Any confrontation will lead to defensiveness in what Argyris calls single loop learning. In such a situation assumptions about issues are never questioned to avoid ambiguity and maintain safety. Under such a situation, when company goals are not being achieved, corrective decisions will be made without analyzing the reasons for the problems. Nobody will challenge the assumptions and corrections will continue to be made by management on the same basis, failing in many cases to correctly address the real problems. Single loop learning is often reinforced by management success in the past, where there has been little failure (or perceived failure) to require any evaluation of the way things are done[38].

Chris Argyris

When people in organizations can question basic assumptions and look at the underlying causes of problems, this according to Argyris is where real organizational learning occurs. This is called double loop learning, which can lead to better organizational and market effectiveness. This type of learning requires a model II behaviour, built on the following assumptions; action based on valid information, action based on free and informed choice, action based on internal commitment to choice and there is constant monitoring of efforts to implement choices[39]. Such an approach to management behaviour builds an environment that can promote learning in the organization and overcome the obstacles to learning.

Argyris developed a workable theory of personality in the workplace, where a universal theory of personality is lacking in modern psychology, radically departing from Freudian concepts. His model also looks at leadership in a dynamic manner rather than the two variables of style and task, that other models have tended to provide as variables. Argyris model is used extensively by organizational development practitioners to facilitate change in organization basic assumptions, utilizing various diagnostic techniques like sensitivity training[40], which Argyris was partly responsible for developing. Argyris and Schon admit that their model may be utopian and its effect of implementation will only alter manager’s espoused theories and only deliver marginal improvements[41]. It will require great effort on the part of a leader to change basic assumptions, values and beliefs in the organization to support model II behaviour in a sustainable manner[42].

Certainly Argyris contribution to management has been one of the greatest of the 20th Century, with his work supported by deep academic research, rather than unsubstantiated opinions. The concepts of learning organizations are generally traced back to him, although Bateson at the same time also developed a similar concept of deuteron learning, first used on the analysis of the double bind personality of schizophrenia[43]. Argyris is considered one of the founders of the human relations movement of management thought along with Maslow, Macgregor and Herzberg.

Reg Revans is a former Olympic athlete and co-worker with E. F. Schumacher at the National Coal Board in Britain. Revans developed the concept of action learning in the coal mines of Britain in the late 1940’s to develop organisational and community learning. In the late 1960’s he moved to Belgium where an Action Learning research project was commenced at the Foundation Industrie-Universitē, in conjunction with industry and a number of universities. Later the Revan Centre of Action Learning and Research was opened at Salford University in the UK.

Reg Revans

Action Learning is an experience based approach to working on meaningful problems as a way to learn. They learn from their attempts to change things as a group and reflect on the challenges of the problem through a questioning insight. The methods of their solutions can be utilised in solving other organisational problems, using the hindsight they have acquired. Groups will have a facilitator who will look at their assumptions and beliefs and provide feedback and scrutinise their mental models used. Action Learning is used to solve complex issues that can not easily be solved, to find solutions for the underlying causes of the problem, determine new directions and maximise opportunities and create new ideas. Revans explains Action Learning with the formula L = P + Q, where L is learning, which occurs through programmed knowledge P, and insightful questioning Q[44].

Action Learning usually comprises the following activities; experiential learning, creative complex problem solving, acquiring of relevant knowledge and co-learning group support. Action Learning is orientated towards learning by doing in a group orientation, focusing on organisational issues, where people play different problem solving roles, and a group decision is made. The steps of the Action Learning process are;

Clarify the objective,

Formation of a group comprising mixed skills,

Analyse the issues and identify actions for resolving them,

Reframe the problem in different ways to seek new perspectives,

Determine goals,

Develop action strategies and test them if possible,

Take action,

Repeat the cycle until the problem is solved by going in different directions, and

Capture the learning through instructor intervention by redefining the problem, find ways to improve performance of the group and identify how their learning can be applied to themselves, group and organisation.

The strengths of Action Learning are considered to be an intelligent and creative way to act and learn at the same time, as this will create the type of work environment needed for the complex environments organisations face today. It is considered both a good method for solving complex problems and at the same time assist in changing organisational culture to more creative learning values, which will be reinforced by the tangible results gained from the process. Action Learning will also enrich the participants as individuals in assisting them in facing everyday problems in life. The downside is that Action Learning requires organisation and a skilled facilitator to run the programs. How the program is designed will be critical for the success of the outcomes. If management will not recognise that it could benefit from the views of others and not willing to question basic assumptions, the Action Learning group will not achieve much. Such an approach to decision making can feel threatening to many managers security and make them feel vulnerable, as it involves taking risks. Action Learning is also hard to measure its benefits in tangible measurables in the short-term.

Action Learning is now used by many management schools and consultants to train CEOs around the world. One of the mistakes management makes about this tool because of its simplicity is to fail to realise that the method requires a change in values on the part of management to make it work in a sustainable manner within the organisation. Action Learning has some elements of double loop learning and an organic approach to management problem solving in a highly participative manner, which is very different from the way many organisations actually work today, as it does away with a lot of formal structure.

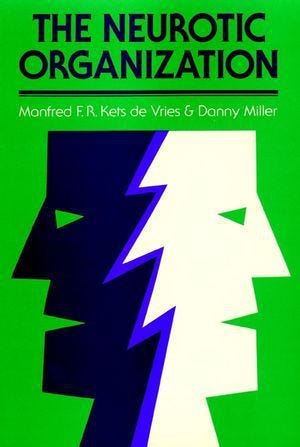

Manfred Kets de Vries and Danny Miller wrote a speculative book based on psychoanalytical theory applied to organisations to examine the dysfunctions of human personality on organisational effectiveness. They postulated that organisations were very closely mirrored by the personalities of senior managers. As with humans, organisational strategy, structure, decision making and orientations can display a normal to neurotic tendency, which will cause organisational dysfunctions. This invisible influence is ignored by management and needs to be diagnosed and remedied.

Kets de Vries and Miller outlined the potential organisational dysfunctions that management should look out for[45];

· The influences that top management’s neurotic styles of behaviour can have on organisational functioning. For example, strong need-achievement tendencies will influence leadership behaviour, locus of control will affect strategy, paranoid characteristics will develop suspicion and mistrust of others, compulsiveness will develop pre-occupation with perfection, dramatic styles will develop excessive drawing of attention to self with a narcissistic pre-occupation for activities and incapacity for focus, a depressive style with feelings of guilt, worthlessness and inadequacy of being at the mercy of events and a schizoid style where there is detachments and on-interest in the firm.

· Groups will develop fantasies, which serve the needs of the members. For example, The manifestation of a common enemy where most of the group becomes focused on, leading to inactivity, short-sightedness, misdirection and non-productiveness. Groups become dependent on one person who is idealised and make no decisions without their approval. Groups live in a false hope of waiting for an event that will come and change things, and their behaviour is affected.

· Individuals, unconsciously treat a current relationship as though it were an important relationship from the past, like a parental figure or sibling from early childhood that has many conflicts unresolved. Thus through this re-enactment, transference of the relationship causes the individual to behave intensely and inappropriately.

· Destructive types of superior/subordinate relationships characterised by control, smothering of initiative, constraining of growth and essentially making them puppets or when the superior takes no interest in subordinates, offering them no guidance, support or security. Each of these behaviours carries injustices and dangers for the organisation.

· The effects of emotional challenges of home and work on the manager and effects on behaviour and satisfaction and job performance.

· Anxiety within the organisation and fears of loss of status and self image, giving rise to resistance to change through a variety of defence mechanisms. These mechanisms block awareness of important facts and data and inhibit responses to them. For example, something has been lost, but continue to act as though nothing has happened, i.e., product distribution, a contract, etc.

Ket de Vries and Miller then outline the key challenges and dynamics relevant to the organisation, where key stages must be worked through to develop change acceptable to all members of the organisation. Organisational neurotic tendencies must be neutralised so that the organisation is able to scan the environment clearly for opportunities and develop strategies, methods of work and structure that are appropriate and effective. Ket de Vries and miller’s work did not become popularist, although Ket de Vries is considered one of the most influential management thinkers in Europe today. His ideas, although taken up in the organisation culture paradigm, where ignored in the cognitive area and are only now just beginning to be examined more closely in entrepreneurial research coming out of Europe over the last ten years.

David Kolb is Professor of Organisational Development at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, where he teaches and researches in the filed of learning and development and founder of Experience based Learning Systems. He published his learning styles model in 1984. Kolb postulates that different people prefer different types of learning styles which he identifies four distinct learning styles[46],

Diverging (feeling and watching) - People preferring this style are able to look at things in multiple perspectives. They are sensitive to people, events and the environment. They prefer to observe rather than act, tending to gather information and use imagination to solve problems. They are people orientated, tend to be emotional, strong in the arts and have broad cultural interests. Diverging people perform better in situations that require ideas-generation, i.e., brainstorming. People with the Diverging style prefer to work in groups, listen openly to ideas and relish personal feedback.

Assimilating (watching and thinking) – This style is a concise, logical approach, where ideas and concepts are more important than people. Assimilating people like clear explanations and prefer to look at abstract concepts, logical ways, rather than the practical approach. They excel at understanding wide-ranging information and are able to filter, channel and organize it into a clear logical format. Assimilating people are suited for information and science careers. In formal learning situations, they prefer readings, lectures, exploring analytical models, and having time to think things through.

Converging (doing and thinking) - People with a Converging learning style can solve problems and will use their learning to find solutions to practical issues, from ideas and theories. They prefer technical tasks, and are less concerned with people and interpersonal interaction. People with a Converging learning style are more attracted to technical tasks and problems than social or interpersonal issues. They can solve problems and make decisions by finding solutions to questions and problems, thus suited to specialist and technology areas. People with a Converging style like to experiment with new ideas, to simulate, and to work on practical applications.

Accommodating (doing and feeling) - The Accommodating learning style is 'hands-on', and relies on intuition rather than logic. These people use other people's analysis, and prefer to take a practical and experiential approach. They are attracted to new challenges and experiences, and carrying out plans. They commonly follow instinct rather than logic. People with an Accommodating learning style will search for information rather than carry out their own analysis. This learning style is useful in tasks requiring action and initiative. People with an Accommodating learning style prefer to work in teams to complete tasks, like to have goals and experiment with different ways to achieve it

David Kolb

Learning undergoes a four stage cycle, where immediate or a concrete experience provides a basis for observation and reflection. This is assimilated and developed into an abstract concept producing a new mode for action which can be actively tested through new experiences.

Most people have strong preferences for a given learning style. They develop their preferences during their development. Kolb identified our development stages as[47];

Acquisition - birth to adolescence - development of basic abilities and 'cognitive structures'

Specialization - schooling, early work and personal experiences of adulthood - the development of a particular 'specialized learning style' shaped by 'social, educational, and organizational socialization'

Integration - mid-career through to later life - expression of non-dominant learning style in work and personal life.

Our choice of learning style is influenced by two pairs of variables: concrete experience (feeling) verses abstract conceptualization (thinking) and active experimentation (doing) verses reflective observation (watching). Feeling/thinking and doing/watching are opposites or dialectic in Kolb’s terminology, which means they are conflicting and we cannot achieve both at the same time. So our learning style will be the product of two decisions[48];

'grasping experience' or how to approach a task by watching (reflective observation) or doing (active experimentation), and

'transforming experience' or our emotional response to the experience, by preferring thinking (abstract conceptualization) or feeling (concrete experience).

People placed in a learning environment that has stimulus not coherent with their preferred learning style, will face problems. For example, people who prefer the Assimilating learning style will not be comfortable without notes and instructions. People who prefer an Accommodating learning style are likely to become frustrated if they are forced to read lots of instructions and rules, and are unable to get hands on experience. Knowing a person's learning style enables learning to be orientated according to the preferred method, where people will respond better to stimulus. Our ability to take on new styles and integrate them together can be developed over time.

Kolb’s model provides a way for us to understand individuals’ different learning styles and shows a cycle of experiential learning that can be applied to all styles. Kolb’s work is heavily influenced by the earlier works of Rogers, Jung and Piaget. His work was considered groundbreaking and these methods are commonly used around schools, universities and companies around the world. Kolb’s work has great significance about how we perceive and look at opportunities and formulate strategy and how people in organizations learn and behave.

Peter Senge is the Director for Organizational Learning at the Sloan Business School at MIT in Boston. He was one of the high profile academics during the 1990’s and propelled the concept of Learning Organisation into the management vocabulary. Senge defines the learning organisation “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together”[49]. Such organizations according to Senge will be able to face the rapidly changing environment with flexibility and adaptive ness, driven by peoples willingness and capacity to learn at all levels. However current organization structures and form are not conducive to learning and people although having great capacity to learn, do not have the tools needed. Senge also identified seven learning disabilities which are responsible for organizational failure[50];

1. I am my position,

2. The enemy is out there,

3. The illusion of taking charge

4. The fixation on events

5. The parable of the boiled frog

6. The delusion of learning from experience

7. The myth of the management team

Senge postulates that it is internal systems rather than external threats to an organization that causes most crisis within an organization. If this is correct, then the underlying causes and patterns of behaviour, becomes the most important issue for an organization. Thus there must be change in the way companies are structured and decision making processes undertaken. Senge lists a number of rules which organization should follow to make these fundamental shifts[51];

1. Today's problems come from yesterday's "solutions"

2. The harder you push, the harder the system pushes back

3. Behavior grows better before it grows worse

4. The easy way out usually leads back in

5 - The cure can be worse than the disease

6. Taster is slower

7. Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space

8. Small changes can produce big results, but the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious

9. You can have your cake and eat it too, but not at once

10. Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants

11. There is no blame

Senge stated that relationships are usually not of a linear nature and the principals above will be understood when we can change our linear, unidirectional causation way of thinking. Causality can be traced back through feedback loops, so the causal reasons for effect can be identified, as well as what is affected by it. Feedback is not a one-way flow and there are reciprocal influences, sometimes with immediate effect and sometimes with delays. Understanding the whole will enable seeing the process of change, rather than a mere snapshot of events, which are viewed as isolated.

Peter Senge

Senge believes that people want to be part of something bigger than themselves to grow and this is where they have opportunities to ‘re-create’ themselves. The prevailing method of learning in organizations is adaptive learning focused on survival, but for a learning organization there must also be generative learning, organizational learning disabilities can be overcome. Generative learning requires a mastering of five disciplines;

· systems thinking; seeing the world and events as a whole, where forces behind them are related. This helps us to see relationships and helps us to see how to change things effectively with minimum effort, i.e., to find leverage points in the system.

· personal mastery; the process of continually deepening and enriching our personal visions, the focusing of energies, developing patience and seeing reality objectively.

· mental models; are unconscious metaphors of how we see things, which influence how we act. If we can understand how we see things, we are in a better position to see reality more objectively.

· building shared vision; to develop a shared picture which will create commitment, rather than just compliance by individuals, and

· team learning; is the ability of the group to rid themselves of their assumptions and begin to think together. This must be done openly without anyone trying to win.

These disciplines can be focused towards seeing wholes, rather than parts, seeing people as active participants, rather than helpless reactors and to creating the future, rather than reacting to the past.

Senge and his team spent many years developing this process. However companies found it extremely difficult to implement as managers were unwilling to give up power, orgainisations didn’t give enough flexibility and authority to staff, individuals were weary about taking on the responsibility, managers and employees just simply didn’t have the skills and the process was undermined by organizational politics, something which is not directly tackled in Senge’s process. Learning organizations are fundamentally different from authoritarian organizations and it was beyond management to let go and make these radical changes. Learning organization is not a quick fix as many had assumed, but a daunting task requiring exploration of individuals performance, personality and ambitions in life, something beyond many peoples willingness to commit to. There are few organizations that resemble Senge’s model and while business wants to develop long term growth and stability, their focus is on enhancing brand recognition and status[52], intellectual capital and knowledge and product development and ensuring production and distribution efficiency[53], and solid financial returns[54]. There have been many suggestions that Senge’s model is just too idealistic and perhaps ahead of its time because of its revolutionary approach[55] and that it will take people to really make a commitment to organizational life in new ways. In 1994, Senge with his colleagues published the fieldbook[56] providing more ideas and suggestions about how to develop the process of learning organization.

It had long been known that the brain was divided into two spheres, where the left side thought serially and the right side thought spatially or holistically[57]. However, thinkers in creative thinking began defining more specific parts of the brain as origins of specific types of thinking. De Bono had developed his four wheels metaphor of human thinking to explain information processing and patterning of the brain[58]. Ned Herrmann developed a whole brain metaphoric model consisting of four quadrants to explain thinking style preferences. Hermann had a degree in physics and worked at the human resource department of General Electric and after years of research on creativity and the brain, released various parts of the brain directed our thinking in different ways.

Ned Herrmann

Herrmann believed the brain was physically and metaphorically divided into four quadrants, each with its own language, perception, gifts and ways of knowing and being[59]. These four quadrants, represent four distinct thinking processes[60];

Left Side: works on logic, words, structures and analysis. It is sequential and time bound (masculine).

Quadrant A: Thinks in terms of numbers and words. Will solve problems using logic based on certain assumptions and tend to reduce the complex to simple. In business they honour agreements ahead of experience and facts above intuition. They prefer to avoid emotions, sticking to facts and logic. They often appear cold, aloof, alone and sometimes arrogant, overlooking human considerations in their decisions. They know about money and how things work and think in-terms of bottom line. People dominated by quadrant A thinking would include accountants, engineers and surgeons.

Quadrant B: Task orientated and results driven. There are some similarities with quadrant A type thinkers, as they take a verbal and linear approach, rejecting any ambiguity. Where A wants to know the facts, B will want to know whether it has worked in the past. B is hands on and will want to get things done and will reject the analysis from A. Quadrant B thinkers work well in a world of rules and procedures. They have the ability to focus on one thing at a time and persist until things are done. They are perfectionists in detail and demanding towards themselves and their subordinates. They seek security in working to rules and procedures and strong at creating order out of chaos. B people are often seen as boring, small-minded, intensive and anti-social. They seek control and don’t handle change well and find it difficult to handle emotions. People dominated by quadrant B thinking would be bookkeepers, administrators, bureaucrats and clerks.

Right Side: works with emotions, pictures, whole entities, inter-relationships and synthesis. It is holistic and time-less (feminine).

· Quadrant C: Thinks visually and holistically. These people are sensitive, receptive and moment to moment mood changers. C people are aware of people around them and are emotional and spiritual. The care for and want to help others. They are also empathetic, nurturing and musical. They are however adverse to people of different quadrants, as they don’t like dealing with facts, goals, time and money. Communication is important to them and relationships are more important than tasks and content. C people are seen by others to be agreeable, pleasant, supportive of harmony, sentimental and always people orientated. They are often thought of as non-conformists by A and B people. Cs thinking processes are interpersonal, emotional, feeling base, kinaesthetic and feeling based. These people are affected by mood in decision making. People dominated by quadrant C thinking would be teachers, social workers, nurses, trainers and musicians.

· Quadrant D: Thinks interpersonally, kinaesthetically and emotionally. These people are excellent at new ideas and thrive on the excitement over them, due to their possibilities, surprises and uncertainty. Quadrant D people are not good at working with others because they are non-verbal and abstract in their concepts. They find it difficult to adhere to deadlines. They don’t like structure and loath working in groups and see the world in visions and images. However they are imaginative, creative, artistic, fanciful and open minded. Facts are no good to them as experience. Quadrant D people see people from other quadrants as impediments, but need them to help turn their visions into reality. They are risk takers, impetuous, rule breakers, like surprises and curious. Quadrant D people think about the big picture, cutting edge or making breakthroughs. Quadrant D people are most likely to be found in art and design and architecture. They would like to be explorers, scientists and researchers.

Communication is the best way to see manifestation of quadrant thinking in people. According to Herrmann, single quadrant dominate people are less than 5% of the population and about 38% are have two quadrant dominance, with influence from the other quadrants[61]. People who have double dominance along the same hemisphere are integrated and their thinking processes are strengthened, but when double dominance is across the hemispheres will experience both strengths and disadvantages, as there will be conflicts, rational logic verses emotion, the future against the past and people verse things, etc. However on the positive side it can lead to a powerful combination of abilities. Approximately 34% of people are triple dominant thinkers[62], this gives the person the ability to communicate to three quarters of the population in the metaphors they understand. Only 3% of people have four quadrant thinking[63], which gives them the power to move across quadrants and see things in multiple perspectives and communicate to the whole population.

The four quadrant model provides and excellent way to view thinking and understand behaviour. This model is used to develop creativity in individuals and groups through Herrmann’s consulting company which uses a questionnaire to measure cognitive preferences of people, the Herrmann Brain Dominance Instrument (HBDI). The Herrmann model is becoming popular in cognitive psychology to look at questions in entrepreneurial decision making, which is a rapidly growing area of research. Arora and Faraone believe four quadrant thinking is a must for the development of strategy, so balanced appraisals, taking all factors into account can be made and maximum creativity developed within the organisation. The ability to harness and synergise different quadrant thinking people in the organisation will be one of the most important jobs for the leader in the future[64].

Art Kleiner and George Roth developed a tool of how to learn from the organisation’s own experiences, so lessons can be put into effective future action. They call this technique Learning History, which involves writing a narrative in one column about an important organisation event like a product launch, new opening, or new initiative and in the other column those involved write down their reflections, comments, observations and feelings about the event. The narrative can then be used for discussion, where lessons and conclusions can be drawn. This organisational learning involves sharing the information, ideas, thought and feelings, so that lessons and conclusions will be shared by all. Kleiner and Roth argue that this form of organisational learning is very valuable as it can create communal agreement about issues, where it can be translated into more effective action in the future[65]. This method is very similar to business case studies at management schools, which are an important source of learning from the real world. Learning history takes the case study approach into the group’s own organisation. Although the concept has some great reflective possibilities in developing strategies, it has not caught on in the business world.

Art Kleiner

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

References:

[1] Arora, V., K. and Faraone, L., (2001), ‘21st Century Engineer-Entrepreneur’, Proceedings of the 2001 American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference and Exposition, reprinted in (2003) IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, 45, 5., October.

[2] Watson, J., (1930), Behaviorism, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

[3] Luthans, F., (1977), op. cit., P. 283.

[4] Allen, B., P., (2003), op. cit.

[5] Kelly, G., (1980), ‘Psychology of the Optimal Man’, in Landfield, A., W. and Leitner, L., M., (Eds.), Personal Construct Psychology: Psychotherapy and Personality, New York, Wiley.

[6] Kimble, G., A., Garmezy, N. and Zieglar, E, (1974), General Psychology, 4th. Ed., New York, The Ronald Press.

[7] Newman, W., H., Summer, C., E. and Warren, K., E., (1972), The Process of Management, 3rd. Ed., Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall.

[8] Polva, G., (1945), How to Solve it?, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

[9] Hutchinson, J., G., (1971), Management Strategy and Tactics, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

[10] Beer, S., (1981), Brain of the Firm, Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, P. 52.

[11] Beer, S., (1981), op. cit., P. 53.

[12] Hunter, M., M., (2006)

[13] Gowda, M., V., R. (1999), ‘Heuristics, Biases and the Regulation of Risk’, Policy Science, 32., pp. 59-78.

[14] Osborn, A., F., (1953), Applied Imagination, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons.

[15] Whiting, C., S., (1955), ‘Operational Techniques of Creative Thinking’, Advanced Management, October.

[16] Adams, J., L, (1986), The care and feeding of ideas: a guide to encouraging creativity, Reading, Mass., Addison-Wesley.

[17] Gaynier, T., (1999), ‘Problem Solving Software Delivers WOW! Solutions’, Machine Design, 71 (19), P. 164

[18] Gordon, W., J., J., (1961), Synetics, London, Collier-Macmillan Ltd.

[19] Newman, W., H., Summer, C., E. and Warren, K., E., (1972), The Process of Management, 3rd. Ed., Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall.

[20] Berne, E., (1964), Games People Play, New York, Grove Press.

[21] De Bono, E., (2003), Sur/Petition: Creating Value Monopolies When Everyone Else is Merely Competing, Singapore, Allscript.

[22] Witkin, H., A., Lewis, H., B., Hertzman, M., Machover, K., Meissner, P., B. and Wapner, S., (1954), Personality through perception: An experimental and clinical study, New York, Harper.

[23] Witkin, H., A. and Goodenough, D., R., (1977), ‘Field dependence and interpersonal behaviour, Psychological Bulletin, 84, pp. 661-689.

[24] Witkin, H., A., Moore, C., A., Goodenough, D., R. and Cox, P., W., (1977), ‘Field dependent and field interdependent cognitive styles and their educational implications, Review of Educational Research, 47., pp. 1-64.

[25] Vrij, A., van de Steen, J. and Koppalaar, L., (1995), ‘The effects of street noise and field independence on police officers’ shooting behavior’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, pp. 1714-1725.

[26] Weller, H., G., Repman, J., Lan, W. and Rooze, G., (1995), ‘Improving the effectiveness of learning through hypermedia-based instruction: The importance of learner characteristics, Special Issue: Hypermedia: Theory Research and Application’, Computers in Human Behavior, 11., pp. 451-465.

[27] Richardson, J., A. and Turner, T., E. (2000), ‘Field dependence revisited 1’, Educational Psychology, 20, pp. 255-270.

[28] Collins, J., N., (1994), ‘Some fundamental questions about scientific thinking’, Research in Science and Technological Education, 12, pp. 161-173.

[29] Simon, H., A., (1957), Administrative Behavior, 2nd. Ed., New York, Macmillan, P. 20-36.

[30] McClelland, D., C., (1975), ‘An Advocate of Power’, International Management, July, P. 28.

[31] Argyris, C., and Schon, D., A., (1974), Theory in practice: A theory of action perspective, Reading, Mass., Addison-Wesley.

[32] Argyris, C., (1964), Integrating the individual and the organization, New York, Wiley.

[33] Argyris, C., (1961), Leadership and Interpersonal Behavior, New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, P. 331.

[34] Argyris, C., (1957), Personality and Organization, New York, Harper & Brothers, P. 53.

[35] Argyris, C., (1957), op. cit., P. 74.

[36] Argyris, C., and Schon (1974), op. cit.

[37] Argyris, C., and Schon (1974), op. cit.

[38] Argyris, C., (1991), ‘Teaching Smart People How to Learn’, Harvard Business Review, May-June.

[39] Argyris, C., and Schon (1978), Organisational learning: A theory of action perspective, Reading Mass., Addison-Wesley.

[40] Argyris, C., (1964), ‘T-Groups for Organisational Effectiveness’, Harvard Business Review, March-April.

[41] Schein, E., H., (1980), Organizational Psychology, 3rd. Edition, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall, pp. 129-130.

[42] Argyris, C., and Schon (1978), op. cit.

[43] Bateson, G., (1972), Steps to an ecology of mind, New York, Bellantine.

[44] Revans, R., (1979), Action Learning, London, Blond and Briggs.

[45] Kets de Vries, M., F., R., and Miller, D., (1984), The Neurotic Organization, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

[46] Kolb, D., A., (1976), The Learning Style Inventory: Technical Manual, Boston, McBer & Co.

[47] Kolb, D., A., (1984), Experimental Learning: Experience as a Source of Learning and Development, Englewood Cliffs, NJ., Prentice-Hall.

[48] Kolb, D., A., (1984), op. cit.

[49] Senge, P., (1990), The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization, New York, Doubleday, P. 3.

[50] Ibid. Ch. 2.

[51] Ibid. Ch. 4.

[52] Klein, N., (2001), No Logo, London, Flamingo.

[53] Leadbeater, C., (2000), Living on Thin Air: The New Economy, London, Penguin.

[54] Hutton, W., (1995), The State We’re In, London, Jonathan Cape.

[55] Van Maurik, J., (2001), Writers on Leadership, London, Penguin.

[56] Senge, P., Roberts, C., Ross, R., Smith, B. and Kleiner, A., (1994), The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization, London, Nicholas Brealey.

[57] Lumsdaine, E., and Binks, M., (2003), Keep on Moving: Entrepreneurial Creativity and Problem Solving, New York, McGraw-Hill., P. 47.

[58] De Bono, (1993), op. cit., P. 55.

[59] Herrmann, N., (1995), The Creative Brain, 2nd. Ed., USA, Quebecor Printing Book Group, P. 1.

[60] Ibid., P. 53-87.

[61] Ibid, P. 86.

[62] Ibid, P. 89.

[63] Ibid, P. 93.

[64] Arora, V., K. and Faraone, L., (2001), op. cit., P. 111.

[65] Kleiner, A., and Roth, G., (1997), ‘How to make experience your company’s best teacher’, Harvard Business review, Sept-Oct.