Before the 1960s, strategy was referred to as “generalship”, “the art of war” and being concerned about managing army campaigns[1]. Strategy was first used in the conduct of business in the early 1960s by Chandler[2], who developed strategic concepts along the thoughts of the industrial economics school[3], business policy[4], and into a prescriptive model with objectives set by the management group which utilized defined strategies to attempt achieving their goals in what was termed corporate strategy[5].

Ansoff postulated that strategy is a matter of combining products with the markets selected by the firm, where the firm continually monitors these markets and makes decisions to enter and exit. Ansoff introduced gap analysis as the key to making decisions about markets to enter and developed the concept of synergy, where the return from a company’s combined resources, should be greater than the sum of its parts. Ansoff’s concepts were well received at the time, but the difficulty of completely understanding the practicalities and implementation proved harder than the concepts. Ansoff in later works stated that firms were often paralysed by analysis and stipulated five key elements that were critical to the firm’s success; 1. No single formula will work for all firms, 2. The most important strategic variable is turbulence in the external environment, 3. The aggressiveness of the strategy must match the strength of the turbulence in the environment, 4. Management must have the capability to implements strategy, and, 5. The key internal variables are cognitive, psychological, sociological, and anthological[6].

Corporate strategy in the 1970s became concerned with firm size, market penetration, market share, vertical integration, diversification, mergers and acquisitions, and general portfolio theory. It was generally believed that large size, diversification, and market dominance would reduce risk and diversified companies could be managed as divisions, as part of a corporate portfolio. These strategic business units (SBUs) would operate almost independently with their own objectives, strategies, costs and revenues, and profit centres.

Around this time, an Australian Bruce Henderson developed the Boston Matrix. This tool was developed on the hypothesis that high market share in growing markets was the most profitable field a firm could be within. This concept proved very popular as it could indicate visually potential strategy and was simple and easy to understand. This innovation created the ‘off the shelf’ consulting culture in corporate America and embedded consultants into the board rooms of many corporations. Other consulting forms quickly developed their own modified versions of the matrix, of which the General Electric and McKinsey Matrix are best known. The Boston Matrix created the perception that having large market share was desirable, which influenced marketing for many years.

Firm diversification continued to be the trend up until the 1980s when it was realized that in most cases, operating portfolio companies were extremely difficult and that in many cases individual strategy business units were worth more as an independent entity than as part of a conglomerate.

The concept of high growth strategies was further challenged by the belief that it was not necessary to have high market share to be profitable. In the 1980s a number of management writers[7] argued that the costs of seeing high growth often outweighed the extra profitability from pursuing such strategies. In fact the whole concept of growth for the sake of growth was being questioned[8]. The whole strategic planning process was being criticised for being more a political exercise based on compromise, rather than rational decision making and optimization[9]. Strategy was also seen as a discourse of power which only legitimizes existing social hierarchical relationships[10].

George Steiner attempted to make strategic planning more practical by presenting it as a step by step manual[11]. Steiner organized the analytical tools of strategic planning in such a way that they could be used by line managers in the firm, rather than a separate and detached planning department. Steiner argued that strategic planning should be “...inextricably interwoven into the entire fabric of management and not something separate and distinct from the processes of management”[12]. Steiner also stipulated that small business and not-for-profit organizations require strategic planning. Steiner also recognized that executives will have their own personal aims which will influence the whole process. Finally, Steiner was one of the first writers in the area of strategy to recognize that corporations have a social responsibility to society. Steiner offered the corporate world something with much more depth than the matrix that was understandable and practical, and is probably under recognized for his contribution to management theory.

The dominant paradigm during the 1980s came through Michael Porter’s meticulous and detailed descriptions of the environment and firms operating within it. Porter in his first book Competitive Strategy developed a theory of how a firm can examine the environment and develop strategies to achieve long term competitive advantage. This structural-action-performance approach based upon the paradigm of industrial organization[13] became known as the Five Forces Theory[14]. Porter’s second book Competitive Advantage postulated that there are three ways a firm can gain competitive advantage. This can be through; 1. Becoming the lowest cost producer in the market, 2. Being a differential producer in the market, or 3. Being a focused producer in the market. Porter also introduced the concept of the value chain where the internal processes of a firm could be examined in an integrated way to determine the parts of the chain that could create value.

Porter took the strategic focus away from market share competition through cost competition to the plain of differentiation, both firm and product. His works opened up a new way of looking at strategy with new options available to the strategist, where firm based strategies could be developed rather than product/market strategies. Although Porter’s work is highly regarded and become a benchmark in some respects in the strategy world, it is sometimes criticized about the lack of focus on the human aspects of strategy. Other perceived limitation of the work is that it doesn’t explain the role of technology in creating new markets and industries. However Porter himself was once quoted as saying that his models are only a guide for consideration and that firms will have to develop their own specialized strategies according to their own circumstances.

Where Porter was clinical and analytical, Kenichi Ohmae, formally the head of Mckinsey’s Japanese office and now a global consultant was more intuitive in his approach to strategy. Ohmae developed the 3C’s Framework or Strategic Triangle where the corporation itself, the customers and the competition is the basis of all strategy where sustained competitive advantage can exist[15]. Corporate centred strategies aim to develop company strengths relative to its competitors in the functional aspects of the business that are critical to success. These are;

- Selectivity and sequencing: the corporation does not need to have a lead in every function to win, it gain a decisive edge in one function that will enable it to move ahead of its competitors.

- The case of make or buy: Outsourcing of production increases flexibility. Inflexibility of competitors to change and adjust production may have strategic implications.

- Improving cost-effectiveness: can be achieved through reducing costs more effectively than the competition, be more selective in inventory carried and products offered, i.e., cherry picking the most high impact aspects of operations or profitable areas, or share key functions with the other businesses of the corporation or even with other companies to reduce costs.

Competitor based strategies can be constructed by seeking possible sources of differentiation in all company functions. These are;

- The power of corporate and company image.

- Capitalizing on profit- and cost-structure differences: advantage in lower fixed cost to variable cost ratio will be beneficial in sluggish periods where prices can be lowered to gain market share.

- Tactics for Flyweights: When competing against giants, use pricing incentives.

- Have the right balance of resources, i.e., not too many managers, plant and equipment and funds. Too much of any resource is wasteful, inefficient and will cause problems to the company.

Customer based strategies should be the basis of all strategies and the others follow to support them. These are;

- Segmenting by objectives: look at different ways customers use products and segment this.

- Segmenting by customer coverage: trade off marketing costs verses coverage and create the optimum market coverage, as over coverage will only create diminishing returns.

- Re-segment the market: In a fiercely competitive market select a key group of customers and re-examine what they are looking for.

- Changes in the customer mix: Look for changing demography, distribution channels and customer types/size, etc.

Ohmae brought a sort of empowerment to marketing management where they could look at markets in new ways with flexibility. However not many could fully implement the whole strategy triangle as a holistic strategy. Ohmae’s works and ideas are greatly respected and he still consults to a large number of corporations and governments today.

During the 1980s some interest emerged in some of the old military strategy texts as some guidance for potential business strategies. Translations and narrations of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War became popular. Sun Tzu’s The Art of War was written 2,500 years ago and was most probably the first comprehensive book of military strategy ever written. Sun Tzu saw strategy as a tool in warfare, primarily out of sight of the enemy, aimed at gaining advantage and defeating an adversary by fighting as few battles as possible[16]. Military strategy has influenced business strategy as it has a similar objective of achieving a desired result and winning. Marketing warfare literature at the time examined leadership, general management, motivation, intelligence gathering, and types of marketing weapons, tools, and logistics. Some of the important principals of Sun Tzu’s strategies that can be seen as relevant to business strategy are summarised below:

- Business is extremely important to the owner so thorough planning is necessary

- Avoid if possible direct competition against competitors (i.e., find a market where there is no competition)

- Emulate as much as possible the strengths of your competitors and build your strengths where your competitors are weak

- Ensure you have a planned exit strategy if necessary

- Know your competitors well, you will have a better chance of success

- Good leadership is a powerful motivator of followers (wisdom, sincerity, benevolence, courage, strictness)

- Show by example

- Develop shared values in your organisation to gain commitment

- Develop competitive advantage and make full use of it in the marketplace

- A powerful and efficient leader is indispensable to the success of the firm

- Have a good technical background

- To be competitive, a company must be able to capitalise on various changes in the economy, business and social environments and develop strategies accordingly

- Must realistically understand what is in and outside of your control

- Position yourself close to the resources you need and markets

- Strength is a relative concept, no absolute superior or inferior strength, it is how you arrange your resources that can bring success

- Hide your strengths and weaknesses from your competitors so you have the element of surprise in the marketplace

- Seek out as much information about your competitors, markets and customers as possible

- Delegate subordinates with enough authority to get the job done

- Training is an important method of achieving efficiency

- A combination of benevolence and strictness is the key to guaranteeing loyalty of your staff, and

- Be transparent in your reward systems so employees know what they will receive.

Sun Tzu outlined four general types of warfare strategies, offensive, defensive, flanking, and guerrilla strategies. In addition to the numerous translations of Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, some very successful and influential books like Al Ries and Jack Trout’s Marketing Warfare and Wess Roberts Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun were published. Warfare strategy is also influential upon the writings of Philip Kotler[17]. Warfare strategy also influenced Levinson’s guerrilla marketing concepts for entrepreneurial and small business.

Although the military metaphor has declined in popularity in favour of other metaphors, many authors have attributed Asian business success to the doctrines of Sun Tzu[18] and been influenced by his philosophies[19]. This may have some positive bearing in the business strategies of some businesses, which are quoted as examples in books[20]. But as other authors have commented, most businesses start out finding the correct business strategies by nothing more than trial and error until they find the winning set of strategies for their businesses[21].

During the mid 1980s and 1990s alternative approaches to Porter’s structural, Ohmae’s intuitive approach and military theories emerged. Some saw the importance of strategic investments in firm specific resources, especially intellectual property that was difficult for competitors to imitate. The dynamic capabilities approach was seen as a means to cope with rapid technology change in high-technology industries like computers, IT, communications, and semiconductors, etc., where new ways to build competitive advantage could be achieved. Many companies like IBM, Texas Instruments, and Philips appeared to pursue these resource-based competitive strategies, aggressively deploying their intellectual property assets into their competitive strategies. However this was met with mixed results as competitors could take the advantage through competitive imitation, leap-frogging technology, or developing alternative forms of technology that the market more readily accepted.

Nevertheless the concept of innovative advantage emerged as being an important aspect of a firm’s long-term sustainable competitiveness, which led to the focus on innovation management in the management literature through the 1990s. Rothwell[22] argued that a firm’s management flexibility and responsiveness to the market supports innovative advantage [23] . Christensen[24] argued that the right type of organization must be prepared for the job at hand and identified three sets of factors that affect what an organization can do; 1. Resources as the most visible factor of what a firm can or cannot do, 2. Processes that create value as they transform both formal and informal inputs into outputs, and 3. Values that drive the direction the firm will head. Christensen’s RPV framework is a useful tool in understanding the difficulties firms have in coping with change. However strong values can bring rigidity as we saw in the US automobile industry and the Australian menswear company Fletcher Jones that refused to relocate its manufacturing plant from Warrnambool, Victoria, Australia or outsource to a low cost country like China, eventually closing its doors due to the strong desire of the founder to maintain the firm’s commitment to selling only Australian made clothes.

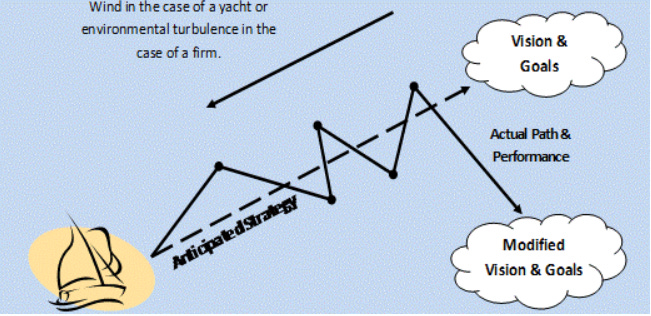

The dynamic character of strategy was recognized by some who believed that there was a tendency for strategy to develop in real life as an interactive social and political process[25]. Strategy is thus a fragmented process of informed socially based incremental decisions with little real coordination[26]. This idea was further developed by Quinn who claimed that management involves guiding actions and events that eventually lead to a conscious strategy in a step-by-step process which he called ‘logical incrementalism”[27] . Thus strategy is actually continually evolving and changing. Strategic decisions tend to be made incrementally through a multitude of decisions rather than a formal strategic planning process. This process occurs with interaction between the organization and the environment in an emergent manner[28]. Changes to strategy occur as the result of organizational learning. This process of incremental strategy change can be metaphorically shown by a yacht tacking against the wind in an effort to move forward, as depicted in figure 1. The actual path of the yacht is the revised course it takes to reach the planned location to compensate for the effect of the wind. It is not always a case of an entrepreneur changing the market, but the enterprise may change as the environment changes, the person changes, and new objectives are picked up as time goes on.

This type of metaphor tends to see strategy formation and implementation as an ongoing process of continuous reassessment and reformation in a way that Constantinos Markides describes strategy[29]. This comes from regular re-conceptualization of what the business is really about, which requires a review of how things should be done in the existing business, in what he called strategic innovation[30]. Strategic innovation occurs when a company identifies a gap in market positioning, moves to fill that gap and finds a new mass market. This occurs in three ways, a) new emerging customer segments or existing customer segments which are neglected by competitors, b) new customer needs emerging or existing customer needs which are neglected by competitors and c) new ways of producing, delivering or distributing existing or new products or services to existing or new customer segments.

However, strategic innovation, according to Markides[31] is difficult to achieve in organisations, due to structural and cultural inertia and rigidity. Markides suggests that companies must be prepared to ask basic questions about the way they are doing business, in order to move to strategic innovation; however this is difficult for companies making profits to do as they become embedded in a comfort zone and are hesitant to perceive future issues related to their strategic and financial wellbeing. Companies that can move to strategic innovation are those who look strategically, rather than financially or artificially create a positive crisis to activate the organisation into positive thinking.

Figure.1. The process of incremental strategy change depicted metaphorically by a yacht sailing against the wind, where it has to modify course regularly (tacking), so it can sail at an angle to the wind.

Other writers took similar views seeing strategy as something partly deliberate and partially unplanned[32]. The unplanned part of strategy is emergent like Mintzberg[33] describes, resulting from appearing opportunities and threats in the environment which result in ad hoc strategies or ‘strategies in action.” These “strategies in action” result from informal, unintentional decisions and actions taken which are not intended to be strategic. There is no evidence to suggest that the performance of a firm is any poorer than if strategies were deliberately planned.

In order to achieve success, Garry Hamel and C.K. Prahalad[34] argued that a firm’s end must be reconciled with its means in what they call strategic intent. Strategic intent is an ambition, aspiration, vision or dream that has enough emotional and intellectual energy for attempting its fulfillment[35]. Thus strategic intent is the driver of strategy in providing a point of view and sense of direction as to where the long-term market and/or competitive position will be, a view as to how this unique position can be achieved, and the emotion, motivation, and energy to start and carry on this journey. Strategic intent sets a challenge or identifies barriers that need to be overcome, such as for example, being the most successful business within an industry i.e., all personal computers and notebooks in the world will use Microsoft Windows, or Coca Cola will be available in every place in the world, or coming into the market with a specific novel product, i.e., mobile phones will be replaced by the iPhone and books will be replaced by the iPad, etc. Strategic intent is more than an idea; it is an emotionally charged desire to achieve. It is a sense of excitement about getting there in the future and is a sense of destiny to achieve something. This sense of destiny must be shared within all members of the organization for the firm to succeed in its mission. Strategic intent implies that the perception of a lack of resources is not considered a major obstacle to growth and development, as the degree of ambition is more important and will drive an entrepreneur to find ways and means around this[36].

Strategic intent should not be a rigid concept; it should slowly evolve through the journey of implementation where strategy creation and implementation become fused together. When this concept of fusion between strategy crafting and implementation is focused towards the exploitation of appearing opportunities, strategy shifts and remains aligned with new opportunities maintaining strategic direction[37], which should produce the best results.

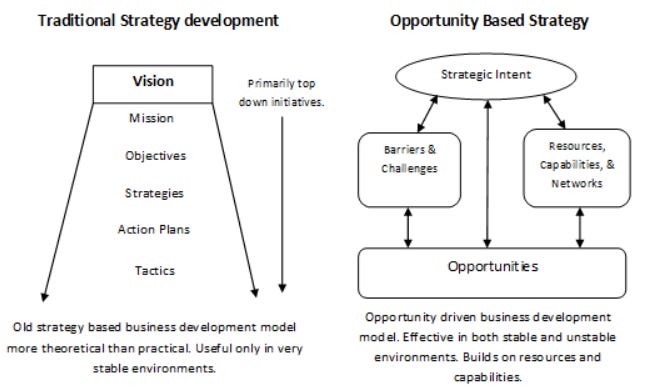

Strategy is therefore not about formal strategic planning sessions, followed by a step-by-step process of developing a mission, objectives, strategies, actions plans, and tactics in sequence. Strategy is about a much more “earthy”, “organic”, “fly-by-wire”, opportunistic, learn as you go process. Strategy should be opportunity based in which new products, services, raw materials, processes, markets, and organizing methods can be introduced to create new means-ends relationships that create value to customers, resulting in a new stream of revenue to the firm[38]. These opportunities are progressively found during the life of a firm through systematic search, passive search, fortuitous discovery, and learning[39]. Strategy drives these opportunities that are discovered, where the original concepts may change and be modified as learning or retrospective sense making occurs[40]. And the strategy itself is guided by the types of resources and capabilities a firm has at its disposal in an evolutionary process[41]. Figure 2. shows the differences between traditional strategy development and opportunity based strategy development.

Figure 2. A comparison between the traditional strategy and the opportunity based strategy models.

The ability of a firm to survive continuous environmental change is the ability of a firm to constantly reinvent itself[42]. Success brings with it rigidity, complacency, and over confidence which can make a firm’s capabilities and products irrelevant, if it develops this mind-set. Arie de Geus identified four key traits that companies that prospered for 50 years or more possessed[43]. They are the 1. The ability of the firm to adjust to the changing environment, 2. The ability to build a community with personality, vision, and purpose, 3. The ability to build and keep relationships, and 4. Conservative financing. Such a company could perpetuate itself and endure for decades. Such an organization according to de Geus[44] is capable of learning, which is a management theme taken up by Senge and others as concept of ‘the learning organization’.

Strategy has been described in the military metaphor (Sun Tzu, guerrilla marketing), the sports metaphor (flanking, running plays, offensives, defensives, recoveries), the phallic metaphor (thrusts, control, and dominance), the oceanic metaphor (carps, sharks, dolphins, the pool, the 3 rd wave, 4th wave, blue and red oceans, etc.), and the eco-system and the biological metaphors (feedback, entropy, inertia, survival of the fittest, viral, etc.). This results in there being no firm and agreed consensus as to any definition of strategy[45], which could be the case because strategy is highly multidimensional and situational according to firm, market, level of competition, industry, place, and time, etc.[46]. For this reason, strategy is a practical rather than a theoretical matter, as strategy is required to make things happen. The effectiveness, validity, and truth of strategy are about how successful it is for the person or firm that applied it. If management is accepted as an art rather than a science, then the possibilities of strategy widen. There is no right and one way of doing things. If strategies were aligned with colours, the basic colours have a very limited number of ways to create them through mixing, as do the basic strategies in business. But once a person looks beyond the various shades and mixes of primary colours, great possibilities open up.

Originally published in Orbus July 2012

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

Notes and References

[1] Drucker quoted the 1952 edition of the Concise Oxford Dictionary. See: Drucker, P., F., (1985), Entrepreneurship & Innovation, New York, Harper, P. 209.

[2] Chandler.D. (1962), Strategy and Structure, Cambridge, Mass, MIT Press.

[3] Hitt, M.A., Keats, B.W., & DeMaiie, S.M. (1998). Navigating in the new competitive landscape: Building Strategic flexibility and competitive advantage in the 21st century, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 22-42.

[4] Learned, E.P., Christensen, C.R., Andrews, K.R., & Guth, W.D. (1965). Business Policy: Text and Cases, Homewood, Il., Irwin.

[5] Ansoff, I. H. (1965). Corporate Strategy, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[6] Ansoff, I.H. (1994). A Contingent Paradigm for Success of Complex Organizations, Milestones of Management, Switzerland, Schaffer Poeschel.

[7] Woo, C. & Cooper, A. (1982). The surprising case for low market share, Harvard Business Review, Nov-Dec., pp. 106-113, Levinson, J.C. (1984). Guerrilla marketing: Secrets for making big profits from your small business, New York, Houghton Muffin Co.

[8] Schumacher, E, F., (1973), Small is Beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered, London, Abacus.

[9] Mintzberg, H. (1978). Patterns in Strategy Formation, Management Science, Vol. 14, pp. 934-948, Mintzberg, H. & Waters, J.A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 26, pp. 257-272, Pettigrew, A. (1987). Context and action in the transformation of the firm, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 24, No. 6, pp. 649-670.

[10] Knights, D., & Morgan, G., (1990), Corporate Strategy, Organizations, and Subjectivity: A Critique, Organizational Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 251-273.

[11] Steiner, G.A. (1979). Strategic Planning: What every manager must know, New York, Free Press.

[12] Steiner, G.A. (1979). “Strategic Planning”, P. 3.

[13] Mason, E. (1949). The current state of the monopoly problem in the US, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 62, pp. 1265-1285, Bain, J. S. (1959). Industrial Organizations, New York, Wiley.

[14] The five competitive forces in the environment are; 1. Customers which will vary in their bargaining power over suppliers and will try to exercise any power they have to lower prices, 2. Suppliers which will vary in their bargaining power over customers and will try to use any power to maximise the prices they receive from customers, 3. Substitutes to the goods and services a firm produces that will limit the prices a firm can obtain from the market place, 4. Rivalry in an industry that will force firms to engage in cutting prices, advertising, promotion, R&D which is likely to reduce profits, and 5. New entrants into an industry that will bring with them resources and the intention of taking market share away from incumbents, which eccelerates the decline of profits in an industry (Porter 1980). The area of profitability within an industry will depend upon where bargaining power is greatest. Thus the aim of strategy is to reduce other firm bargaining power so profit can be maximized.

[15] Ohmae, K., (1982) The Mind of the Strategist: The Art of Japanese Business, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[16] Sawyer, R. D., (1994), Sun Tzu: The Art of War, a translation with historical introduction, Boulder, Westview Press.

[17] Kotler, P. & Singh, R. (1981). Marketing Warfare in the 1980’s, Journal of Business Strategy, Winter, pp. 30-41.

[18] Min Chen, (2004) Asian Management Systems, 2nd Edition, London, Thomson.

[19] Ohmae, K., (1982) “The Mind of the Strategist”, P. 42.

[20] Chen, M., J., (2001), Inside Chinese Business: A Guide for Managers Worldwide, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

[21] Gomez, E. T. & Hsiao, H-H. (2000). Chinese Business in Southeast Asia: contesting cultural explanations, researching entrepreneurship, Richmond, Curzon Press.

[22] Rothwell, R. (1989). Small firms, innovation and industrial change, Small Business Economics, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 51-64, Rothwell, R. (1992). Successful industrial innovation: critical factors for the 1990s, R&D Management, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp. 221-240.

[23] Flexibility is often much easier for smaller firms which have less bureaucracy and formal procedures to deal with than larger firms and thus can respond much more quickly to signals in the market place. However the influence of a small firm within the market place is usually much less than a large firm. Secondly smaller firms may lack the ability to undertake research and development, and need to rely upon outside sources of technology (Steward & Gorrino 1997). Factors like the restriction of technology, remote geographical location, and a mature industry can be a great hindrance to small firm growth (Jones, 2003).

[24] Christensen, C. (1997). The Innovators Dilemma, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, P. 186-187.

[25] Ghemawat, P. (1986). Sustainable Advantage, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 64, No. 5, pp. 53-58, Shapiro, C. (1989). The Theory of Business Strategy, RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 125-137.

[26] Lindblom, C. (1959). The science of muddling through, Public Administration Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 79-81.

[27] Quinn, J.B. (1980). Strategies for Change: Logical Incrementalism, Homewood, IL., Irwin.

[28] Mintzberg, H. (1978). “Patterns in Strategy Formation”.

[29] Markides, C. C. (1999). A dynamic view of strategy, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40, pp. 53-63.

[30] Markides, C. C. (1997). Strategic Innovation, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 38, pp. 9-23.

[31] Markides, C. C. (1999). “A dynamic view of strategy”.

[32] Moncrieff, J. (1999). Is strategy making a difference? Long Range Planning Review, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 273-276.

[33] Mintzberg, H. (1978). “Patterns in Strategy Formation”.

[34] Hamel, G. & Prahalad, C.K. (1989). Strategic Intent, Harvard business review, May-June, pp. 63-76,

Hamel, G. & Prahalad, C.K. (1994). Competing for the Future, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

[35] Hamel, G. & Prahalad, C.K. (1994). “Competing for the Future”.

[36] Marsden, A. & Forbes, C. (2003). Strategic Management for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, In: Jones, O. & Tilley, F. (Eds.). Competitive Advantage in SMEs: Organising for Innovation and Change, Chichester, West Sussex, John Wiley & Sons, P. 50.

[37] Skat-Rørdam, P., (1999). Changing Strategic Direction, Copenhagen, Handelshojskolens Forlag.

[38] Eckhardt, J.T. & Shane, S.A. (2003). Opportunities and Entrepreneurship, Journal of Management, Vol. 29, pp. 333-349.

[39] De Tienne, D.R. (2004). The relevance of theories of change for corporate entrepreneurship scholars, In: Katz, J. & Lumpkin, T. (Eds.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, Vol. 7, London, Emerald Publishing Group Ltd.

[40] Burgelman, R.A. (1991). Intraorganizational ecology of strategy making and organizational adaptation: Theory and field research, Organizational Science, Vol. 2, pp. 239-262.

[41] Lovas, B. & Ghoshal, S. (2000). Strategy as guided evolution, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21, pp. 875-896.

[42] Pascale, R. (1990). Managing on the Edge, New York, Simon & Schuster.

[43] De Geus, A. (1997). The Living Company, London, Nicholas Brealey.

[44] De Geus, A. (1997). “The Living Company”.

[45] Bourgeois, L.J. III (1980). Strategy and Environment: A conceptual integration, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 5, pp. 25-39, Gluck, F., Kaufman, S., & Walleck, A.S. (1982). The four phases of strategic management, Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 9-21, Steiner, G.A. (1979). “Strategic Planning”, Hatten, M.L. (1982). Strategic management in not-for-profit organizations, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 3, pp. 89-104.

[46] Hambrick, D.C. (1983). Some tests of the effectiveness and functional attributes of Miles and Snow’s strategic types, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 26, pp. 5-25.