The Influence of Family and Peers on the Propensity to Become an Entrepreneur

Within the United States nearly 90% of private businesses and 60% of all public companies are family dominated businesses in one form or another (Shanker and Astrachan 2003). Australia, Brazil, Italy, New Zealand and Spain also reflect this. Many well known and Fortune/S&P 500 companies including Marriot, Ford, Walgreens Drugstores, Nordstrom’s Department Stores, Tyson Foods, Mars Candies, Wrigley, SC Johnsons, Coors, Anheuser Busch and Sun Oil were once or still are family dominated companies (Habbershon 2007). Based on this information one would expect the domain of the family to exhort great influence over children. However this is far from the case as parents exhibit only minimal influence over their children in their choices about career and self employment (Kim et. al. 2006).

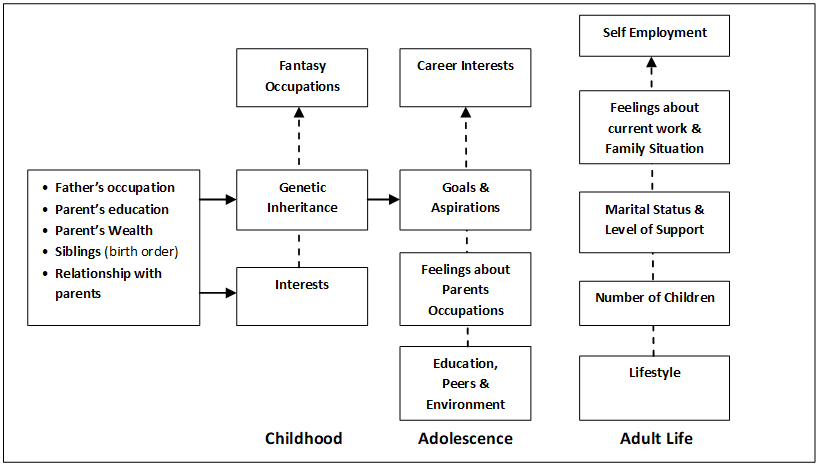

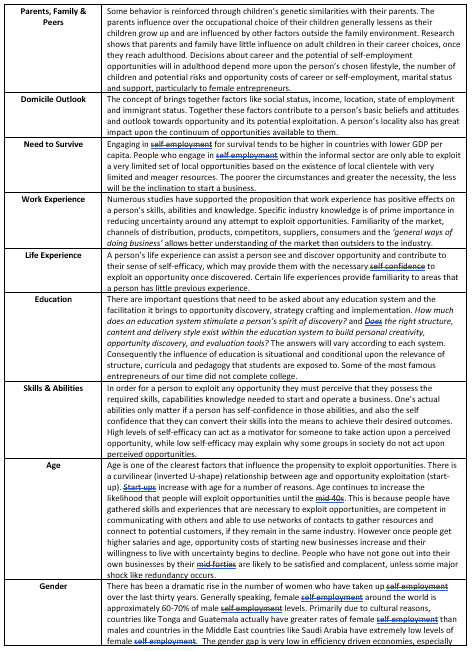

Parental influence tends to follow three distinct stages over their child’s development; childhood, adolescence and adult life. The parents influence over the occupational choice of their children generally lessens as their children grow up and are influenced by other factors outside the family environment.

Parents have the most influence over their children during early child hood through both parenting and genetic inheritance. Parents are the only role model to children in early life and during this period where they learn the social role of family and gender[1]. This is where children pick up many of their early values and behavior which are reinforced with some genetic similarities of their parents. The family environment tends to reinforce the genetic traits of children during this time (Shanahan and Hofer 2005).

Values are instilled in children through child rearing practices, interaction with their siblings, the types of activities the family undertakes, the schools that they go to and the peers they have access to. Children become socially conditioned where they start to pick up the values of their socio-economic class. Sons begin to emulate their father’s socio-economic values through their early childhood socialization, which may lead to the child aspiring to having the same social position in the future (Lichtenstein et. al. 1995). Parents who have high self directive occupations like lawyers, doctors, or university lecturers may install values of high self direction into their children, whereas parents with low self directive occupations like transport drivers and process workers may install the values of conformity into their children (Kohn et. al. 1986). Middle class children may develop a greater sense of entitlement giving them self-confidence to mobilize resources where working class children may like the autonomy they have in childhood and seek occupational autonomy in adult life (Lareau 2002).

During childhood parents play a moderately significant role in influencing specific vocational and occupational choices in their children (Barak, Feldman and Noy 1991). This influence is very strong where the family is immersed within the vocational domain of a farm or a solo country doctor’s practice. However these types of professions are declining rapidly (Aldrich and Kim 2007). During childhood children are heavily influenced by fantasy and may develop aspirations for ‘fantasy occupations’ like an astronaut, fireman, oceanographer, pilot, train driver or policeman, rather than wanting to directly mirror their father’s occupation.

During adolescence children move into their teenage years with very general vocational interests and expectations, having shed their childhood ‘fantasy occupations’. They are in awe of the range of possibilities as teenagers become exposed to teachers, friends, parents of friends, relatives and other people they meet along the road of their upbringing. The blending of their personality traits with the stimulation from the environment and discovery of their own self identity opens up new vocational possibilities and closes others. Only a small number of high school students actively seek information about potential career paths by seeking information or joining in appropriate activities, even though almost all teenagers will have vocational aspirations when asked (Schneider and Stevenson 2002). Teenagers who perceive their families as supportive and having high expectations of them, have higher occupational aspirations (Whiston and Keller 2004). If the father has a prestige occupation, sons may aspire to the same, or if not something with similar prestige (Mortimer 1974, 1976).

Only a minority of children of self-employed parents begin working in the family business at a young age. The children’s time in the family business is usually very short, where they tend to leave for other jobs before they are 21 years old (Aldrich and Kim 2007). Exposure to entrepreneurship within the family may not be enough for a child to learn the tacit knowledge necessary to be successfully self employed (Aldrich et. al. 1998).

Parental influence on career choices by the adolescence years depends upon how their children perceive their parents occupations, which can be either a positive or negative influence (Mortimer 1976).

Research shows that parents and family have little influence on adult children in their career choices, once they reach adulthood (Aldrich and Kim 2007). After adolescence an adult has too many influences upon them. Work experience builds upon what they learnt from their parents, and the number of years of managerial experience is probably more important an influence on a person to enter self-employment to exploit perceived opportunities (Kim et. al. 2006).

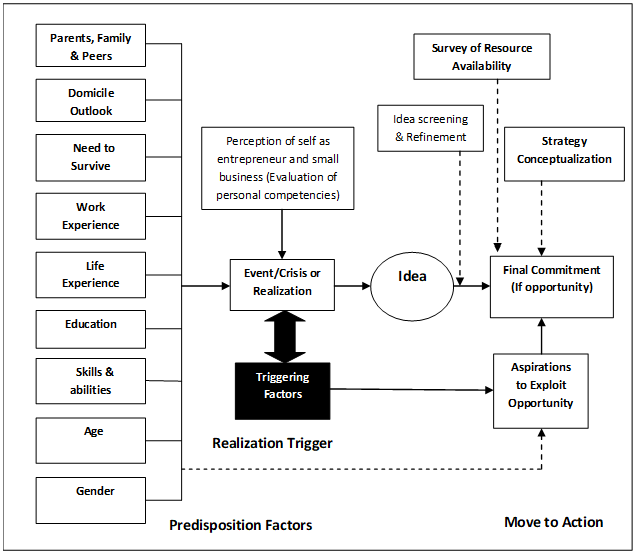

Adults tend to get advice from professional experts in particular areas like lawyers and accountants, etc. (Renzulli et. al. 2000)[2]. Parental assistance to children tends to be restricted to providing loans and gifts to children for start-up capital and providing moral support and advice. If children are in the same industry as their parents, then parental advice may save the expense and time of undergoing trial and error during the start-up phase of the business (Sorensen 2006). However the majority of children enter different industries than their parents, so previous work experience in similar businesses before they start their own is likely to be more valuable (Fairlie and Robb 2005). Decisions about career and the potential of self-employment opportunities will in adulthood depend more upon the person’s chosen lifestyle, the number of children and potential risks and opportunity costs of career or self-employment, marital status and support, particularly to female entrepreneurs (Hisrich and Brush 1983). Figure 1. shows the probable influences of parents and family upon their children’s career choices.

Figure 1. The probable influences of parents and family upon their children’s career choices.

The family, particularly the father and mother play a powerful role in establishing the desirability and credibility of entrepreneurial action for the child (Shapero and Sokol 1982). However, this does not explain why individuals tend not to follow their parents career as one child may consider entrepreneurship as an exciting career option while another may feel that this direction is only for people who cannot get a regular job (Katz 1992). Therefore family background, although having great influence on a person’s attitudes and behaviour can only provide us with a very limited insight into what shapes a person’s aspirations and desires.

There is a tendency for people to seek out the advice of others particularly in the research stage before making a decision or commitment. This can be seen as a mechanism utilized to gain confidence about making a certain move or decision. However too many people delude themselves and listen only to what they want to believe and may avoid seeking advice from people they feel will not agree with them.

Domicile Outlook

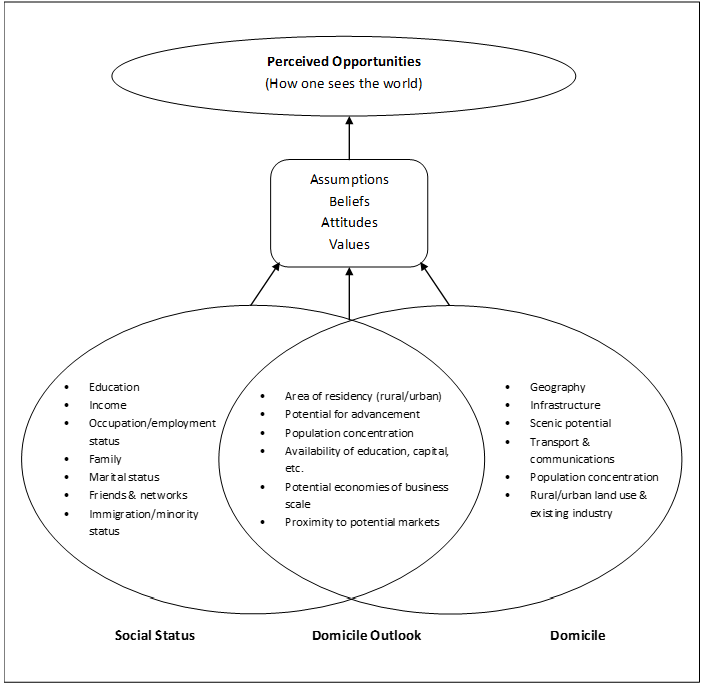

Domicile outlook can be defined as the beliefs, attitudes and views one develops from the position where they live and social status. The concept of brings together factors like social status, income, location, state of employment and immigrant status. Together these factors contribute to a person’s basic beliefs and attitudes and outlook towards opportunity and their potential to exploit it. Domicile outlook is closely related to social status. Social status is itself a multidimensional concept made up of numerous factors including education, occupation, sex, marital status, area of residence and family (Hollingshead 1975). Social status has a strong influence in creating domicile outlooks and domicile outlooks play a role in creating social status.

Social status can enhance or hinder a person’s ability to exploit opportunities. It is generally postulated that social status will increase a person’s likelihood of exploiting entrepreneurial opportunity by the position they are in to convince others of the value of an opportunity, gather resources and organize (Shane 2003, P. 92). According to research, social status increases a person’s power of persuasion (Stuart et. al. 1999). For example inventors with high university rank in Britain are statistically more likely to be involved in start-ups than lower ranked university scientists (Shane and Khurana 2001). Once again in Britain, people of higher social classes were more likely to become self employed (Dolton and Makepeace 1990).

Social status is an important source and determinant of the level of empowerment a person feels they have. Social status also determines how others perceive you and how you connect and interrelate with others. Research shows that 50% of jobs are filled through informal social channels by connections of family, neighbors, and other friends, etc, showing the influence of social status on our lives (Granovetter 1985).

People who become unemployed change their social status, i.e., how they perceive themselves and how others perceive them. For example, unemployment brings a change in a person’s circumstances which often forces consideration of alternatives that would not normally be considered. As the opportunity cost of self employment decreases (i.e., there are few if any employment options), looking for an opportunity and turning to self-employment becomes more likely (Mesch and Czamanski 1997). The probability of taking the self-employment option during times of unemployment increases with time (Evans and Leighton 1989), unless unemployment benefits keep the opportunity cost of self employment high (Eisenhauer 1995, Alba-Ramirez 1994).

Migrants with language and cultural unfamiliarity seem to be able to undertake the transition through poverty that local indigenous minorities may be locked within (Portes and Min Zhou 1992). Immigrant groups fleeing from wars, political and religious persecutions have been able to transform the economies of the countries they have settled in, such as the Cubans in Florida, displaced colonialists in Morocco, Tunisia and Algiers, East Germans in West Germany, and Koreans and Vietnamese in the US (Krueger 2002, P. 100). Local minority groups may not have the skills that and capital that immigrants have or accumulate and therefore face barriers to self employment. Minority groups with little social capital are consequently restricted to self employment pursuits that require little start-up capital in marginal enterprises (Boyd 2007). Some migrant groups may be aided by the existence of their own communities with their own concepts of social status. These communities may be large enough to start community specific businesses like newspapers, restaurants, and car dealers, etc (Wilson and Martin 1982).

The advantages of social status can be seen where the children of self-employed also have a tendency to become self-employed themselves, either through their family business or their own start-up (Dunn and Holtz-Eakin 2000). Children of self-employed may observe their parents use tacit skills required for an enterprise start-up and carry goodwill through their family name. Likewise people with high education and a relatively high net worth are most likely to engage in self employment to exploit an opportunity (Bates 1995).

A person’s locality has great impact upon the continuum of opportunities available to them. This continuum is widened or narrowed by their social status, skills, access to capital and market access within the area they reside.

Urban areas are usually a large source of opportunity due to the high concentration of people, the high consumption nature of the population, the need for income to survive in the consumption oriented society and the diversity of needs and wants within the metropolitan area. An urban market contributes to potential economies of scale due to close proximity of the business to consumers. The larger the urban area, the greater the scale of opportunities exist. An urban environment attracts increasing human habitation requiring infrastructure, housing, food, waste disposal systems, transport, communications, employment, and governing mechanisms. Although viewing an urban area as an ecosystem maybe radical (McDonnell and Pickett 1990), it operates as a human driven system where opportunity is created out of the need to solve urban generated problems, i.e., needs for housing, transport, consumption, employment and commerce. Social status will effect to some degree the level and scale of opportunities a person is able to realistically contemplate and exploit.

Massive structural changes are occurring in urban areas around the world, changing domicile outlooks. In the industrial countries most craft based and manufacturing industry has exited inner suburban areas where they once thrived. Some areas have made way for trendy inner city living lifestyles where service businesses like launderettes, coffee shops, delicatessens and other specialty service businesses have taken over to capitalize on lifestyle demand. In urban areas that have lost the very industries that once drove urban growth, unemployment, poverty and even destitution are left behind (Guarino 2010). Spurred on by the housing crisis in 2009, now 47.6 Million Americans or 1 in 6 people in the United States are now in poverty according to the US Census Bureau (Muir and Bass 2009). Many of the unemployed are in their 50s with obsolete skills competing with those very much younger for the few jobs now available.

In contrast, cities in Asia are rapidly growing in a similar fashion as the industrial cities of the west did in the 1960-70s. This is particularly the case along coastal China, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta and a number of cities in India. Manufacturing industries bring with them new middle classes and opportunities for business ventures that are needed to satisfy the needs and wants of these emerging classes.

Opportunity in rural areas is influenced by a number of factors, which are summarized below;

1. Geography is one of the most important determinants of opportunity. Topographical features and the transport and communications infrastructure will determine the cost structure of operating a business in any particular area. Isolated areas are basically inaccessible by road and other transport and may not have mobile phone coverage. The population within an isolated area may not have access to much education above primary school and tend to be isolated from knowledge and technology. Any products and inputs for a potential business will be relatively expensive (Maleck 1994). Markets will be extremely small with not enough population to promote any economies of scale. Remote areas are disadvantaged to a lesser degree than isolated areas. Remote areas have access to populated areas through roads and communications. Still the costs of doing business may be significantly higher than in urban areas, but opportunities may exist for higher value contributing businesses in these areas. General access to capital in both isolated and remote areas will usually be very limited or non-existent. Areas adjacent to urban populations provide access to large markets where operational costs may be competitive to urban based businesses. Adjacent rural areas over time may be eaten up by the growing urban sprawl.

2. The scenic aspects of geography provide potential for tourism. Areas where tourism exists may have a wide spread of opportunities for local entrepreneurs to exploit.

3. Transport is critical for opportunities, potential markets and the cost of exploiting them. Transport infrastructure is vital for the wellbeing of a community. The establishment of transport infrastructure like a high grade road, rail or air link may dramatically increase opportunities. Likewise the diversion of vital road arteries away from major towns has a dramatic effect on the wellbeing of local communities that traditionally supported travelers. Road diversion can usually have a devastating effect on local economies. On a national scale, international transport links will partially determine a country’s international competitiveness.

4. Basic infrastructure like utilities, health and education services influence a region’s desirability for settlement. Without basic facilities an area will not be attractive for general settlement, leaving it unpopulated and lacking in potential income earning opportunities. Such areas will be both socially and economically isolated from the rest of the region.

5. Over the last two decades land governance issues has affected the economic viability of land. Government authorities in countries like Australia charge resource rents through water charges to farmers. Farms are also given water allocations which they must pay for. This together with drought has changed the viability of producing crops on the land. In many developing countries land issues are governed by customary law and inheritance. As families of the last generation tended to be large, family parcels of land have been divided up to the point of being uneconomic to work. This has created much idle land in some countries where reform of these customary laws is required to enable farmers to access economic plots of land. Land around the world has generally degraded through salinity, erosion of top soils and the effects of climate change, changing the set of crop options to open to farmers.

Many rural areas around the world are in crisis. Australia has been hit by a long drought which is slowly grinding rural communities to a halt. With tightening credit, many rural families are being forced off the land. Chronic shortages of labour are affecting harvests and production. The inequality of educational pathways between rural and urban youth will potentially inhibit the ability of today’s rural youth to scan the environment for opportunities and exploit them in the next generation (Golding 2001).

In countries like Papua New Guinea, economic and social inequality is increasing between the rural and urban population. Rural population has fewer opportunities from limited economic activity in their regions. Their disadvantages are caused by remoteness from urban markets, the high cost and deterioration of transport services, poor access to services, lack of private and government investment and environmental pressure on the eco-system due to illegal activities such as logging. In Papua New Guinea nearly half the people living in rural areas live under the poverty line (Baxtor 2001).

Through South-East Asia, rural areas are facing similar problems. Many rural areas lag behind in national development, unable to benefit from the high levels of growth in the region. Some countries are focusing on building infrastructure in urban areas due to the very rapid urban population growth at the expense of rural areas. Lack of rural investment is leading to higher rural unemployment rates where a large percentage of rural youth population is leaving for the cities in search of job opportunities (Hunter 2006). This leaves an aging farmer population in rural areas with low education levels, resources and capital. In some parts of the region there is a feeling of powerlessness, with a lack of ideas, opportunities and matching skills, so very few are willing and able to embark upon new business ventures, due to a general feeling of hopelessness and despair (Hunter 2008).

Communities in isolated and remote locations may have adequate food and housing to survive and live a relatively comfortable life of which they have known for generations. Some of the younger people from these isolated communities may go outside and work so they can remit funds back to their families for buying of staple goods, so there is no financial poverty. However these conditions create a poverty of opportunity where isolation and lack of market access deprives them from making a sustainable livelihood. The poverty of opportunity is a situation which prevents a community from leading productive and satisfying lives. Due to the sparse population any business without outside markets will not be economical or even able to survive (Tafuna’I 2002). More often than not these communities are also subject to external threats such as logging and rising sea levels along coastal areas and islands.

Poverty is a major barrier to opportunity in a number of ways. Poverty is characterized by lack of capital, financial, physical and human, capital depreciation, through over fishing, over harvesting and over logging, etc. Land in rural areas is derogated through loss of top soil and nutrients, lacking any infrastructure for irrigation during dry seasons. Communities may be isolated through almost inaccessible mountain ranges, poor roads and high transport costs. Often communities may have social customs which create barriers and blocks to advancement, like views on women’s role in society, etc. This may be aggravated with high fertility rates. However the single most important hindrance to getting out of what Jeffrey Sachs (2005, P. 62) calls the poverty trap is the ability to be creative and innovative, so opportunities can be constructed or discovered.

The concept of domicile outlook is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Concept of Domicile Outlook

However opportunities exist within the lowest income earning communities around the world as a market and a source of production. Some of the world’s largest companies have developed new and innovative ways to develop markets within the bottom income strata of society. For example Kao Philippines many decades ago developed shampoo in the form of a powder sold in satchels for daily use through ‘moms and pops’ stores throughout the archipelago. Likewise Indonesian detergent manufacturers developed low cost crème detergent for laundry and dish washing that was affordable by the poorest communities in Indonesia. Hindustan lever has followed the lead of their local competitor Nirma in India with low cost detergent that could be used on a daily basis (Prahalad and Hart 2002).

Further, the advent of micro-credit has enabled increased consumption by the poor of things they would not normally be able to purchase. CEMEX a transnational cement company based in Mexico, found a novel method of accessing low-income customers by sending their sales representatives into villages to sell material packages with small monthly repayments to build home extensions, that would otherwise take years to complete without micro-credit. In Mexico, once children are married they stay at home according to tradition. CEMEX through encouraging the formation of savings clubs and offering materials packages (Patrimonio Hoy) with micro-credit has enabled families that normally couldn’t afford home extensions undertake them. Grameen Bank was formed to service the poor using a “peer lending model” that other banks could not consider because of the small loan size, need for collateral and contractual enforcement. This success led to the formation of Grameen Telecom which offers a village phone service in Bangladesh.

In Thailand, a number of companies manufacture and distribute ingredients for simple street stall dishes like noodles. To make it easier for a street stall vendor to start-up, the companies supply everything including the physical stall itself. This innovation in Asian street stall food has gone so well that most street stall foods in Thailand now carry franchised brand names, which give consumers the confidence in the quality and taste they will get. New innovations like selling products in kit form to create new cost structures, decentralizing and miniaturizing production, using micro-credit, developing new channels through new alliances will enable the creation of new markets that were not there before among the poor.

Creating small decentralized production within communities of the poor of the world was a vision of E. F. Schumacher (1973) in his seminal book Small is Beautiful. Production is being broken down into nodal production units, saving on tremendous capital costs (Prahalad 2004, P. 16). For example, Nestle collects dairy milk from individual smallholders to produce their milk products in India, thus saving on investment in their own large dairy farm estates and Jaipur Rugs has 40,000 contract workers weaving at home producing their carpets.

Building new supply and value chains is the key to empowering the poor in remote locations to potential markets. For example, the ‘One Tambon One Product’[1] program in Thailand was initiated nationwide by the government in 2001. Products are selected for promotion on the basis of their quality and export potential and include food items, textiles, woven handicrafts, and non-edible herbal products, etc. The project is supervised by a national OTOP committee with regional and provincial level committees. The local committees help not only to identify potential products but also provide advice on production (e.g. quality control, packaging and designs that make them attractive to domestic and/or export markets).

The original objective of “One Tambon One product (OTOP)” project was to enhance social protection through;

1. A social protection and risk management system with participation from the private sector and the people,

2. The sustainability of local handicraft products, social protection and skill development, changes of livelihood and coping strategy in relations to the OTOP project,

3. Collaboration modules among public agencies (Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Industry) and local government organizations for expanding social protection to informal workers,

4. Culture: role of producers, consumers and modes exchange Best practices in area-based sufficiency economy, e.g. provincial development or provincial cluster development, and sufficiency economy index/indicators,

5. Survey of the application of sufficiency economy in various sectors, e.g. agriculture, industry, and

tourism, etc., and possibility for expansion in different areas, sectors

6. Fiscal and financial measures to promote green and clean products and technology, and

7. Marketing strategies/plans to promote green and clean products and technology.

The Thailand OTOP program is based on the Japanese “One Village One Product Movement (OVOP)”. The OVOP movement started 1979 in Oita Japan as a means to promote regional revitalization and autonomy. Each community identified one or more products or industry that was locally specific and distinct. Resources were then concentrated on the production of these products, establishing them as local brands, and marketing them to the entire country or beyond. The program is based on the following principles: 1) Local yet global –the development of globally accepted products that reflect pride in the local culture; 2) Self-reliance and creativity; and 3) Human resource development – Rewarding creativity and industry. Villagers found that their local products turned into national brands, which encouraged interest in their local traditions and products – leading at times to an increase in tourism. Publicized through mass media, research and guidance facilities were established to provide technical support to varying industries; a sales and distribution mechanism for OVOP products was organized, and education and training was offered to industrial and regional leaders. A reward system was also set up for those who successfully implemented the program.

OTOP Thailand is an umbrella concept where multiple programs are combined to enhance product development, skill, technology and marketing through exhibitions, local, regional and international development. OTOP uses a multiple channel strategy framework, utilizing;

Regional Retail Outlets,

Retail outlets in Tourist precincts,

Exhibitions (regional, domestic and international),

Roadshows (domestic and international),

Internet Marketing,

Catalogue marketing,

Permanent central exhibition centre in Bangkok,

Through hypermarkets like MAKRO, Carrefour, Tops and Tesco,

Direct marketing organization, and

International OTOP trade offices.

OTOP now covers all product areas including handicrafts, cosmetics, herbs, essential oils, foods, beverages, wine, produce, textiles and clothing, and many other categories. The OTOP program is now in its third strategy phase of developing international markets and is making agreements with international companies and department stores to carry OTOP products in Europe and Japan (MCOT 2006).

The Fair-trade movement is a trading partnership based on community dialogue, transparency and mutual respect that seeks to develop trade along an equal and equitable partnership. Fair-trade also strives to contribute to sustainable community development through the improvement of trade conditions. Fair-trade was originally developed through religious groups and NGOs work in developing countries to open up trade links with more equity. The formal Fair-trade movement grew out the 1960s student and activist movements against neo-colonial and multinational companies, where the concept of “trade not aid” gained acceptance. Handicrafts during the 1960s were sold through OXFAM stores in the United Kingdom, and eventually volunteer shops opened throughout the rest of Western Europe, and later the United States selling products from the Third World.

During the 1980s the Alternative Trading Organisations (ATO) was formed and widened their scope from handicrafts to focus on the wider issues of commodity trade from South to North. This led to the sale of tea, coffee, fruits, cocoa, sugar, spices, and nuts. Fair-trade also widened its retail scope around Europe and the United States to achieve more than USD 3.6 Billion sales in 2007, increasing at the rate of almost 50% each year[2]. This is still only a very small proportion of total World trade, but according to the Fair Trade 2007 annual report, sales in specific traded product categories represented between 1.0 to 20.0% of total trade in that item in Europe and the United States[3].

The basic principles of the Fair-trade movement are;

The sharing of a common vision where justice and sustainable development are the basis of trade structures and practices, so that everybody can enjoy a dignified life and develop their full potential,

That Fair-trade will be a fundamental driver of poverty reduction and contribute to sustainable development, by connecting those in the South who most need change with citizens of the North who seek greater sustainability and justice,

This will be achieved through;

· Gaining market access for those excluded from the mainstream and value-added markets or those with only access to them through lengthy and inefficient trading chains.

· Encourages the use of traditional forms of production so that social benefits can come back to the community.

· Helps to shorten the trade chain so that more funds will come back to the producers of primary goods, where the basis of the transactions takes account of the costs of production, both direct and indirect, including the safeguarding of natural resources and meeting future investment needs.

· To assist producers connect with the consumer, so producers can learn concepts of social justice and opportunities for change[4].

The Fair-trade system provides two prices to the producer. The first is the Fair-trade Minimum Price which is a guaranteed price that covers the direct and indirect costs of sustainable production, which moves up and down according to the market. The second price is the Fair-trade Premium which is a separate payment for social and economic development in the producer’s community.

In 1988 a Fair-trade certification initiative was developed so Fair-trade products could be sold through wider distribution channels. This led to the formation of the Faired Labelling Organizations International (FLO), an umbrella organisation responsible for the setting of Fair-trade standards, support and certification of producers[5]. The first trademark system identified to people products that met agreed environmental, labour and development standards was launched in 2002 under the authority of FLO-CERT. FLO-CERT is a certification body responsible for inspecting the producers and traders, licensing them with authority to use the trademark.

Fair-trade standards specify the requirements producers must meet to be certified. These standards specify the improvements that producers must make each year. Two basic standards exist, one for small farmers’ organisations and another for hired labour situations. Small farmer organisation standards specify democratic decision making systems and how Fair-trade premiums are invested in the community, as well as requirements for capacity building on both an individual and organisational basis. Standards for hired labour specify that workers receive decent wages and enjoy the freedom to join unions and bargain collectively. Plantations must ensure that there is no forced child labour and occupational health and safety requirements are met. Standards also require that a joint worker-management committee is set up and that premiums be spent to the benefit of plantation workers.

Fair-trade marks are now issued for coffee, tea, rice, bananas, mangoes, cocoa, cotton, sugar, honey, fruit juices, nuts, fresh fruits, dried fruits, canned fruits, quinoa, chutney, muesli, biscuits, jams, sauces, herbs and spices, cakes, wine, beer, cosmetics, baby-food, cotton products, yoghurt, and footballs, etc., sold through department stores, supermarkets and convenience stores in around 50 countries.

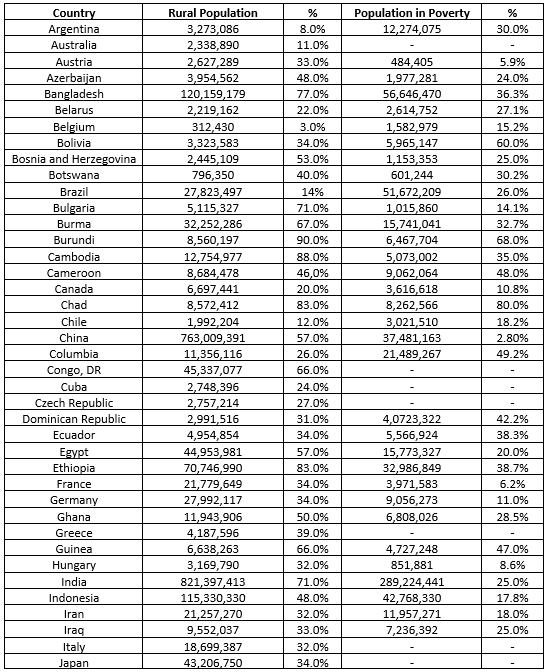

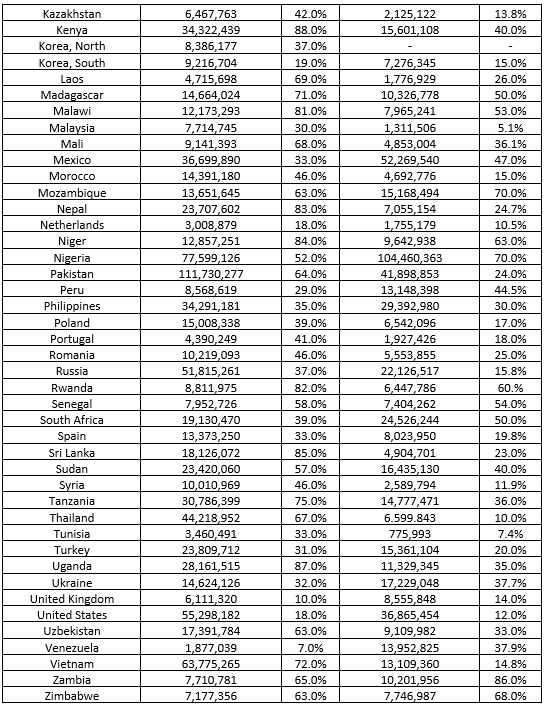

Although some communities have benefitted by the innovations described above, there are so many other communities that suffer from relative and absolute poverty and the poverty of opportunity. Table 2. shows the number of people and percentage of total population living in rural areas and officially in poverty according to various country measurements of poverty in a number of selected countries.

Table 2. Summary of Rural Population and Poverty Levels in Selected Countries[6]

The Need to Survive

Many people for various reasons are unable to gain stable employment. This may be for reasons of age, location, education, disability, necessity to care for young dependents, or economic downturn, etc. As a consequence large numbers of people throughout both developing and developed countries are only able to consider economic activities within the informal sector as a casual employee or in some form of self employment. People from developing countries are driven by poverty, the need to survive and lack of employment choices into starting small business ventures (Reynolds et. al. 2002). Engaging in self employment for survival tends to be higher in countries with lower GDP per capita (Reynolds et. al. 2002). States with social welfare systems with safety nets tend to have less people opening small micro-enterprises in need of survival (Henrekson 2005).

People who engage in self employment within the informal sector are only able to exploit a very limited set of local opportunities based on the existence of local clientele with very limited and meager resources (Bruderl et. al. 1992). The poorer the circumstances and greater the necessity, the less will be the inclination to start a business. This is because of the minimum amount of cash investment needed to start (Rosa et. al. 2008). Some saving must be undertaken first, so self-employment usually comes after some casual work for someone else or borrowing from a relative. Some people will have assets like a piece of land and home, but little cash. These micro-enterprises will be opened in industries with little market barriers like newspaper vending, shoe polishing or repair, car washing, grass cutting, baby minding, laundry, ironing, housework, home assembly (piece work), a market shop, food vending or catering, etc. Approximately 70% of these types of businesses will be single person start-ups (Niefert and Tachouvakhina 2006).

The intention of these micro-enterprises is to achieve certain family goals like send the children to school, build a home back in their village, buy a piece of land to work or raise their own social status (Rosa et. al. 2008). These would be seen as basic needs in developed countries but they are aspirations in developing countries, which require forgoing consumption in the short term for achieving these longer term aspirations.

These micro enterprises tend to grow at much slower rates than opportunity based enterprises with higher capital injections because the person in the micro-enterprise has little time and spare labour capacity left over to develop and expand the business. There may not be any aspiration for business expansion as there may be little opportunity other than satisfying a small niche of local clientele. Also the area of business is likely to be very competitive where gaining extra business will unsettle the micro-social situation in the area leading to anger and even violence from poaching other vender’s customers. Government regulations like HACCP in the food retailing industry, taxation[1], and the cost of employing someone act as further disincentives to expand and get out of the informal sector. People are trapped where they are and become habituated in what they are doing to think of anything different. High competition leads to only a marginal income, leaving little room for saving once weekly living expenses are paid.

The income circumstances of people in developing countries with land and family can also be very complex with multiple sources of income and some self-sufficiency in the production of food[2]. Family members working away from home may supplement incomes, as would a harvest of some crop like paddy in the tropical countries. Alternatively, they may receive some rental income from their rural land and the enterprise they work in is more of a supplemental income. This provides freedom from the necessity to be employed full time and an opportunity to raise their social status, progress with their lives, and/or be independent as a single parent, etc. In this circumstance self-employment is a way of staying out of poverty (Minniti and Arenius 2003) and to some degree being able to determine their own destiny. Thus the most important factor in the ability to start-up a micro-enterprise is the ability to save the initial capital, rather than education skills or employment situation (Rosa et. al. 2008).

Work Experience

Numerous studies have supported the proposition that work experience has positive effects on a person’s skills, abilities and knowledge. Work experience enhances a person’s ability to see opportunities and develop strategy scenarios in industries they are involved. Intimate understanding of an industry leads to less uncertainty. A person within an industry can interpret its meanings in ways outsiders cannot easily understand, leading to advantages in the ability to discover opportunities and develop subsequent strategies to exploit them.

There are a number of different types of work experience that aid the ability to discover opportunities, develop strategy and organize a start-up in an industry where a person has experience in. General and functional business experience includes knowledge and skills in the basic principles and functions of business including finance, sales, technology, logistics, marketing, and organizational skills (Romanelli and Schoonhoven et. al 2001, Klepper and Sleeper 2001). These general and functional business skills assist a person make decisions about business location, product development, quality control, setting of prices, customer service and innovation issues (Lerner et. al. 1995).

Some business skills like sales are more useful than others, where other skills like financial management can be picked up during later periods (Roberts 1991). The closer work experience is related to the specific tasks required to exploit an opportunity, the more proficient the person will be at a start-up and organization of a new firm. People with experience in marketing, new product development and management are more likely to exploit opportunities than people in the financial and accounting areas (Boyd 1990, Klepper and Sleeper 2001).

Specific industry knowledge is of prime importance in reducing uncertainty around any attempt to exploit opportunities (Shane 2003, P. 79). Familiarity of the market, channels of distribution, products, competitors, suppliers, consumers and the ‘general ways of doing business’ allow better understanding of the market than outsiders to the industry (Johnson 1986). Founders of new ventures tend to keep in industries that they are familiar with. This helps to reduce the likelihood of failure (Bruderl and Preisendorfer 1998, Bruderl et. al. 1992, Wicker and King 1989). In contrast, public sector employees in general are less likely to become self employed than those from the private sector (Praag and Pohen 1995), unless specific opportunities to provide services to government evolve.

Prior experience in venture start-ups is invaluable in knowing what to do when an opportunity has been discovered. Many things must be attended to during a start-up that is based on tacit knowledge and situational events; therefore it is difficult to teach these skills through formal education (Jovanovic 1982, Herbert and Link 1988). Prior start-up experience assists in deciding what information to collect to aid in decision making (Duchesneau and Gartner 1990), how to deal with suppliers and customers (Campbell 1992), and what actions to take in what sequence, etc.

Skills relevant to exploiting opportunities can be learned through the observation of others (Shane 1996). Children of entrepreneurs are more likely to exploit opportunities than others because of close observation of their parents during their adolescent years which provides tacit knowledge (Minniti 1999). People who grow up in entrepreneurial environments are more likely to become entrepreneurs themselves (Matthews and Moser 1995). General exposure to friends, neighbors and other entrepreneurs generally increases the likelihood that a person will seek to exploit opportunities (Landry et. al. 1992).

Generally people with little organizing ability are less likely to exploit opportunities (Shane 1996). People with previous business experience are more likely to approach a new venture by analyzing customer’s needs than those who have not started a business before (Shuman et. al. 1985). People with business experience will be more concerned about cash flow and profitability of a business. Previous work experience helps a person develop managerial, financial, attitudinal and general business competence (Goss 1991). Skills that can be learned through work experience and their potential benefits to opportunity exploitation and start-ups are listed in Table 3.2. below. Business experience is in many ways better than formal education because it provides tacit knowledge which is difficult to disseminate through formal structured education. Therefore experience is greatly beneficial when it comes to the opportunity identification and exploitation. According to Kolb et. al. (1985) the most powerful way to learn is by experience.

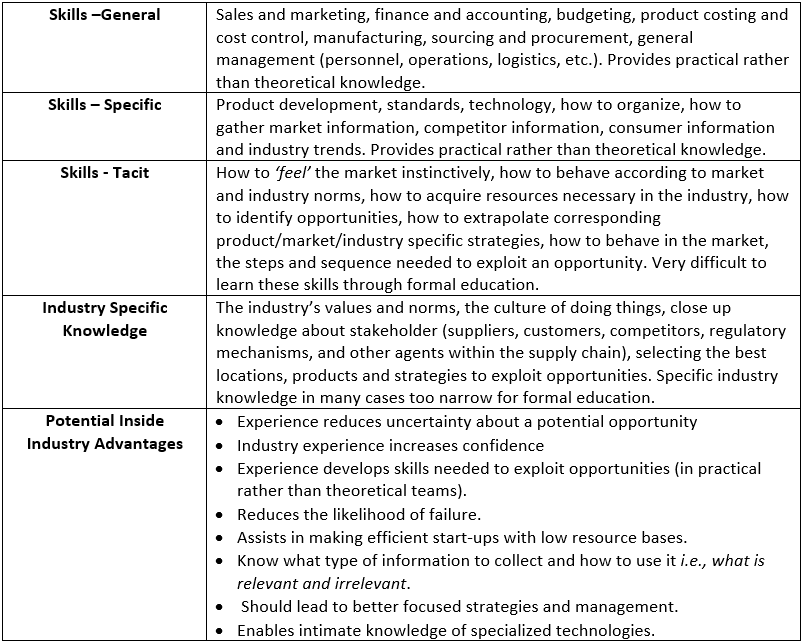

Table 3. Skills that can be learned through work experience and potential benefits to opportunity exploitation and start-ups

Finally it must be mentioned that many companies particularly in the high technology industries like microchips, hard-drives and lasers were formed as the result of employees leaving a firm to set up their own. Examples of companies set-up as spin-offs of ex-employees of other companies include Intel, Advanced Micro Devices, National Semiconductors (spin-offs from Fairchild Semiconductors) and 3Com and Adobe (spin-offs from 3M). Bhide (1994, P. 151) in a study of found that 71% of innovations in new companies were replicated or modified from their concepts in previous employment. When new industries develop, those with experience in a related industry have an advantage over those with no experience in related industries (Klepper and Simons 2000)[1]. People are more likely to take up opportunities if they feel their resources and capabilities are compatible with the potential opportunity (Helfat and Lieberman 2002).

Life Experience

A person’s life experience can assist a person see and discover opportunity and contribute to their sense of self-efficacy, which may provide them with the necessary self confidence to exploit an opportunity once discovered. Life experience is a framework of time and space that serves as a reference for viewing the environment.

Certain life experiences provide familiarity to areas that a person has little previous experience. A person with a general background in marketing and sales may be able to see areas where customers are not satisfied, preferences (Johnson 1986) and gaps within the marketplace (Von Hippel 1986). General knowledge of marketing provides information necessary where opportunities can be discovered (Klepper and Sleeper 2001). Likewise people involved in product development and applications tend to be more alert for new product opportunities (Roberts 1991).

Metaphorically opportunity discovery can be seen like having a puzzle with a missing piece required to complete the puzzle. A new piece of information may be the missing piece that creates an opportunity (Romanelli and Schoonhoven 2001). People who have a wide life experience through having a number of jobs and/or travelled may have information that others don’t (Casson 1995) to complete the metaphoric opportunity puzzle. For example, a Malaysian student studying in the U.K., U.S. or Australia may become exposed to concepts that are yet to exist in their homeland and constitute an opportunity. A sports person or hobbyist with marketing experience may see a potential opportunity within the sport they play or the hobby they partake that is worth exploitation. People with specialized skills like carpentry may see opportunities related to their skills that are difficult for people without those skills to see. People who travel to other countries and return home (McCormick and Wahba 2001) and people who have knowledge others don’t are able to discover opportunities others don’t see (Shane 2003, P. 48). The more geographically mobile a person is the more chance of seeing opportunities (Delmer and Davidsson 2000, Lerner and Hendeles 1993).

Diverse life experience particularly with some relevant skills and competencies will provide a knowledge angle to approach the development of a new business. Relevant knowledge can be built upon with the addition of new knowledge creates a ‘snowball effect’ in building competence to develop and run the business. Businesses can be developed from different knowledge angles, a marketing approach, technical approach or a channel approach to developing the business. For example a person with marketing experience may be able to build up their technical product knowledge as they go along or a person with technical product knowledge may be able to build up their marketing skills as they go along with the venture. This experience is invaluable in providing tacit knowledge which can be applied to specific problems, enabling a person to think of practical solutions based on past events.

A person’s level of self-efficacy is determined by their general success and achievement throughout their life. If one’s life experience has contributed to a feeling of self-efficacy a person is more likely to feel confident about exploiting an opportunity they feel can be exploited successfully (Markman and Baron 2003). Self-efficacy creates optimism that a person can achieve a desired outcome (Bandura 1993). This optimism lowers the amount of perceived risk that a person associates with the opportunity. Life experience sets the limitations of the will. This may sometimes be divided against itself with both the urge to do and the urge to hold back.

Finally, life experience can set the domain limits on the set of ideas that an individual may consider. This self definition upon what is within personal focus creates attention to specific events, objects, and people. Therefore any may see scope for growth. For example, the American railroads stopped growing because managers saw themselves as the in the railroad business. This narrow self definition prevented further growth (Levitt 1960). When a company manufactures electric light globes for example, is the company in the electric business? Or is the company in the consumer products business? Each answer may be right at a given time for a given company, but each answer would lead to the viewing of a very different environment where the company would put its efforts (Drucker 1992, P. 190). Ideas and opportunities are restricted by the narratives we live by.

Education

It is generally believed that that the higher the level of education in the community, the higher will be the propensity to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane 2003, P. 69). This is supported by a number of research studies that found people with a higher level of education than the general population are more likely to exploit opportunities and engage in self employment (Robinson and Sexton 1994, Storey 1994, Reynolds 1997, Bowen and Hisrich 1986). Further studies have reinforced this hypothesis with statistical studies showing that those with professional qualifications (Dolton and Makepeace 1990) and with over 16 years of schooling were more likely to exploit entrepreneurial opportunities and engage in self employment than others (Borjas and Bronars 1989, Bull and Winter 1991).

However there are important questions that need to be asked about any education system and the facilitation it brings to opportunity discovery, strategy crafting and implementation. How much does an education system stimulate a person’s spirit of discovery? and Does the right structure, content and delivery style exist within the education system to build personal creativity, opportunity discovery, and evaluation tools? The answers will vary according to each system. Various systems are based on different objectives, philosophies, outcomes, content and pedagogy. Teachers are trained at different levels and approach teaching from different perspectives. People have different social expectations from the education system that provides for their learning.

Consequently the influence of education is situational and conditional upon the relevance of structure, curricula and pedagogy that students are exposed to. The influence an education system has on a person also depends upon other outlooks one obtains through family, peers and society’s culture (Gupta 1992). Are these factors supportive or contradictory to what a person learns through the formal education system? A poorly framed and structured education system may actually hinder creativity and entrepreneurship (Charmard 1989, Plaschka and Welsh 1990) and promote a ‘get a job’ mentality (Kourilsky 1994).

Many of the entrepreneurial education courses in existence are not put together carefully, nor evaluated or correlated with objective measures of subsequent venture performance by those who have undertaken courses (McMullan et. al. 2001). Many programs are confused about their objectives. Should the course teach about entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship skills, small business or creativity and innovation as life concepts? These all have very different orientations and cultures (Gibb 1987). To enhance a person’s creativity, opportunity discovery and evaluation skills, resource acquisition skills and strategy crafting and organizing skills requires specific concept teaching (Knight 1987). Secondly this material must be taught in ways that maximize learning, such as experiential learning concepts? (Ulrich and Cole 1987, Stumpf et. al. 1991). Education programs must have skill building components like negotiation, leadership, creative thinking, as well as exposure to technical innovation and product development to enhance a person’s ability to exploit opportunities (McMullan and Long 1987).

For an education system to be relevant to opportunity discovery, evaluation, and exploitation, it must improve entrepreneurial judgment by providing people with the analytical ability and an understanding of the entrepreneurial process (Clouse 1990, Casson 1995). Education should reduce the perceptions of difficulty in starting a business (Jackson and Rodney 1994). Most importantly education should increase a person’s perception of their own self-efficacy. Self efficacy is an important trait that enables a person to have the confidence in discovering opportunities and contemplate the feasibility of starting a business (Shapero 1975, Shapero and Sokol 1982). However it must be remembered that self-efficacy is not solely created through education, family, peers and the surrounding society also have great influence (Ajzen 1987, Boyd and Vozikis 1994). For these reasons the effect of education will not be the same on all people.

However some of the most famous entrepreneurs of our time did not complete college. Thomas Edison finished school at 12, Steve Woznick and Steve Jobs did not graduate, and Bill Gates dropped out of Harvard to start Microsoft, while Michael Dell quit the University of Texas to start Dell Computers (Bhide 2000).

Yet another challenge is how to structure an education system so it can be coupled with technical knowledge to enhance a person’s ability to be innovative. Entrepreneurship education without the specific technical knowledge needed to drive particular ventures is not a full education. In general entrepreneurship training courses the student will generally lack any specific technical background and is forced to pick this knowledge up somewhere else. Thus technically educated people who take up some entrepreneurial courses during or after their technical studies will have advantages over those who study a dedicated entrepreneurship course. Those with industry experience will also accumulate tacit knowledge that education has difficulty in providing. This is one of the dilemmas of entrepreneurship education at undergraduate levels at least. Graduate programs may apply incubator programs from engineering and science schools.

Positive education should provide a person the basic skills of how to seek knowledge and use it for whatever purpose it has been sort, i.e., how to learn how to learn. In industries where technology is constantly evolving technical knowledge very quickly becomes outdated. Skill building programs are much more valuable than knowledge building programs, especially in view of the dynamics of technologies and markets. Education must build self learning abilities to assist people develop new knowledge schema for their specific opportunity applications.

Skills and Abilities

There are various skills and abilities a person needs to exploit any opportunity through an enterprise framework (Casson and Della Giusta 2007). Some of the major skills and abilities a person needs are;

1. General Business Skills

Some of the general business functions required to successfully exploit an opportunity within a business environment include; marketing, production operations, human resources, financial, business laws and regulations and general administrative skills. Particular day to day skills required to operate any business include sales, purchasing, supply chain management, general book keeping and accounting, cash flow and general business management. These basic skills enable a person to understand and operate a business within the basic principles of management. There may be a need for more specialized knowledge depending on the type of business operation, e.g. retail, wholesale, importer, exporter, wholesaler, marketing company, assembler or manufacturer, etc. There is usually a tendency that a person has better competencies in some areas than others and any business orientation and operational style will be biased towards those competencies. For example a person with a strong sales background may give the company a sales emphasis, whereas a person with a production background may position the operation as a production orientated company.

2. Technical Skills

Technical skills are important for the processing, manufacturing or some other specific aspect of a business. Strength in particular technical skills provides a person with product, processing and manufacturing knowledge. Without a strong core of technical skills a business has no technology base which may or may not be needed within the gamut of the chosen industry the entrepreneur has chosen to operate within. Technical knowledge also functions as an anchor between the enterprise and the industry. Technology empowers the enterprise and at the same time can lock a business into a specific industry based on a specific technology. Nevertheless knowledge in specific technologies may be a necessary prerequisite for industry entry, existence and product competition. Any specifically developed proprietary knowledge or intellectual property may assist in creating some sort of competitive advantage or barriers to entry for other potential competitors.

3. Start-up Skills

Start-up skills are very important for converting an idea into an enterprise to exploit the perceived opportunity. This phase usually commences after the opportunity has been identified. Start-up skills range from the tacit knowledge necessary to undertake the preliminary steps needed to commence trading operations and the more specialized aspects of the business that need to be specifically created for the enterprise, like specialized production layouts or retail configurations. The general start-up tasks include registering a business entity, setting up a bank account, finding a premises, creating accounts with suppliers, employing early employees if need be and purchasing immediate necessities like office equipment etc. The specific specialized aspects of the enterprise that require setting up and development include the identified technologies that will be exploited, the new product development process and the initial identification and building up of early customer relationships. It is during this stage that the planned innovations that will provide an anchor for the enterprise within its chosen industry are developed, whether it is a technical, process, organizational or supply chain innovation.

4. Planning Skills

Planning skills are required to map out the direction of the enterprise so it can successfully exploit the perceived opportunity it was formed for. This involves simultaneous planning concerning marketing, sales, product development, organizational development, financial and resource acquisition. Only after all these aspects are coordinated and developed together will the enterprise platform physically exist with the ability to exploit the selected opportunity.

5. Analytical and Conceptual skills

Analytical and conceptual skills are needed to both visualize any opportunities, enable the visualization of an enterprise to exploit perceived opportunities and continue guiding the strategic direction of the enterprise once it is in operation. Analytical skills gather and organize information in such a way that conclusions can be drawn upon its meaning, significance or importance to the enterprise, that may lead to future action. Conceptual skills are about broad thinking and the general outlook of particular situations based on the environment, enterprise and self.

6. Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal skills involve the interaction with others for the purposes of resource acquisitions, sales, communications with potential funding organizations and communications with potential employees. Interpersonal skills are also very important in the process of persuading people to support certain aspects of the enterprise, whether as a customer, employee, supplier or other form of stakeholder.

7. Networking and negotiation Skills

Networking skills are needed to develop relationships with people and companies that are potential stakeholders and have some influence over the enterprise’s future. The enterprise founder/manager should be an extravert to some degree and be comfortable about meeting people. Negotiation skills are very important in the negotiation of leases, rents, purchase prices of inputs, salaries, and last but not least with customers. Without sound negotiation skills there is a great chance that the enterprise will suffer cost disadvantages from paying high prices for leases and other inputs and lower revenues because of selling goods or services below the price someone may be able to get if they were a better negotiator. Negotiation sells are a key determinant of cost efficiencies for the enterprise, where poor skills in this area would be a great disadvantage.

8. Leadership Skills

Leadership skills are very important to develop loyalty, commitment, dedication, motivation and sharing of the enterprise vision with others, especially employees. Good leadership creates extra energy within an enterprise. Leadership involves the playing of various roles which include nurturing, guiding, advising, showing example, directing, showing the way and focusing the organization. In start-ups and young enterprises the leader sets the vision and is one of the most important influences on the development of the culture within the enterprise. Good leadership also requires a good rounding of all the other skills mentioned above and any weaknesses would denigrate the quality of enterprise leadership, most possibly leading to a less effective operating organization.

In order for a person to exploit any opportunity they must perceive that they possess the required skills, personal competencies, and knowledge needed to start and operate a business (Tutkimusraportteja 2009). This comes from self-efficacy, the belief that one can execute a certain set of tasks and behaviour (Boyd and Vozikis 1994). Self perception reflects a person’s innermost thoughts and feelings on whether they have what it takes to successfully perform the tasks needed. One’s actual abilities only matter if a person has self-confidence in those abilities, and also the self confidence that they can convert their skills into the means to achieve their desired outcomes (Bandura 1986, 1997). General self efficacy is central to a person’s human functioning and is based on what people believe rather than what is actually the case (Markman et. al. 2002). High levels of self-efficacy can act as a motivator for someone to take action upon a perceived opportunity, while low self-efficacy may explain why some groups in society do not act upon perceived opportunities. For example, when people in poverty have no drive, no energy and no self-esteem, they become defeatist. If they are placed in an environment which encourages and supports them, i.e., a windfall in a lottery or a good job, the same people would become go getters and self confident (Kao et. al. 2006). Self-efficacy is a reasonable predictor of the propensity for someone to perceive opportunities (Krueger and Carsrud 1993).

Persistence is a very important attribute in the start-up and consequent development of an enterprise and this is influenced by how a person perceives themselves and their situation. According to Shapero (1975) self-efficacy is central to a person seeing the feasibility of starting a business. Self-efficacy is believed to be influenced by experience and other social factors like observational learning, vicarious experience, social persuasion, parental and peer support, and personal judgments, physiological state and age (Ajzen 1987a, Boyd and Vozikis 1994, Shapero 1975, Shapero and Sokol 1982). Therefore any new venture decision will be influenced by a person’s perception of the skills necessary to initiate tasks, regardless of any other triggers (discussed later in this chapter) that motivate any desirability. Someone who feels that they don’t have the necessary skills, even in the situation of necessity, will tend to look for other ways of surviving before looking at the option of starting a business, as they don’t feel personally capable of taking a risk of that magnitude (Morales-Gualdrón and Roig 2005).

Finally, our perceived opportunities are to some degree based on our self perception of our skills and abilities. Our self-efficacy influences our courses of action, level of effort, how we perseverance, our amount of resilience in the face of barriers and obstacles, how we cope with adversity and whether our own thoughts are self-hindering or self-aiding to our actions (Woods and Bandura 1989, Markman et. al. 2002).

Age

Age is one of the clearest factors that influence the propensity to exploit opportunities (Parker 2004, P. 106). According to Scott Shane (2003, P. 89) there is a curvilinear (inverted U-shape) relationship between age and opportunity exploitation (start-up). Start ups increase with age for a number of reasons, Younger people have just reached maturity and are ready to focus upon something. They have been educated and have little restriction because of mortgages and loan payments to consider when making decisions. They are used to living through odd hours and are at their physical peaks. Available employment opportunities are less than previous generations had access to so settling into a new business is just as much of an adjustment to make as settling into a new job.

Age continues to increase the likelihood that people will exploit opportunities until the mid 40s (Holtz-Eakin et. al. 1994). This is because people have gathered skills and experiences that are necessary to exploit opportunities, are competent in communicating with others and able to use networks of contacts to gather resources (Freeman 1982) and connect to potential customers, if they remain in the same industry. However once people get higher salaries and age, opportunity costs of starting new businesses increase and their willingness to live with uncertainty begins to decline (Shane 2003, P. 89). People who have not gone out into their own businesses by their mid forties are likely to be satisfied and complacent, unless some major shock like redundancy occurs.

A recent study of age and exploitation of opportunities has uncovered a trend in baby boomers over 50 engaging in start-ups (strangler 2009). Start-ups by the 20-24 age group at this point of time very low, according to statistics in the United States (Ballou et. al. 2008). According to Ballou et. al. (2008) in every year since 1996, Americans aged between 55 and 64 had a higher rate of entrepreneurial activity (roughly 33% higher) than those aged 20-34. There could be several reasons why this could be so. For example, the availability of less ‘lifetime’ work available to baby boomers has decreased the opportunity cost has increased the attractiveness of going into one’s own business (Farber 2006). Further, as life expectancy is increasing (78 for females and 76 for males), baby boomers are changing their attitudes and are looking for activities like further education, work and leisure to pursue (Hansen 1993). Figure 2. shows the propensity for start-ups by age.

Figure 2. Age Distribution of Propensity to Exploit Opportunities (Start-Ups) in the United States

The above are U.S. trends and few studies exist to determine whether other countries are following suit with start-ups during later age. Differences in start-up trends between countries will affect national innovation and productivity levels, which will affect aggregate economic growth in the future (Bloom et. al. 2007). It is not knowledge creation itself that creates innovation, but the use of knowledge in start-ups that creates economic activity (Aces et al. 2006). Therefore start up and age distributions trends will be expected to affect the exploitation of opportunities in individual countries.

Gender[1]

There has been a dramatic rise in the number of women who have taken up self employment over the last thirty years. Generally speaking, female self employment around the world is approximately 60-70% of male self employment levels. Primarily due to cultural reasons, countries like Tonga and Guatemala actually have greater rates of female self employment than males and countries in the Middle East countries like Saudi Arabia have extremely low levels of female self employment. The gender gap is very low in efficiency driven economies[2], especially the Latin American countries, with women exceeding men in Brazil. The Eastern European countries exhibit much lower rates of women self employment than men. Male self employment in the innovation driven economies is approximately twice that of women, excepting Germany, where almost the same number of females are self employed and in Japan, Italy and France where female self employment rates are extremely low (Bosma and Levie 2010).

Statistically[3] women are attracted to the extremely competitive services sector where it is difficult to develop any competitive advantage and therefore only marginally profitable. Women are locked into the services sector in aggregate because they know and have experience in this area, frequently lack technical skills for manufacturing and high-tech sectors, have difficulty obtaining the resources needed (Bruni et. al. 2004) and have minimal access to the necessary networks (Aldrich et. al. 1996, Brush 1992). Due to these disadvantages women’s businesses tend to exhibit slower growth than male owned and operated businesses (Brush 1997). However, female participation in both management and self employment in both the traditional and non-traditional sectors is expected to increase in the coming decades as more females are staying single pursuing careers (Hamer 2010) and universities are experiencing large surges in enrollments in business and technical degrees by more women than ever before (Guess 2007, Jaschik 2006), especially in Asia (Shirahase 2000).

Gender is a culturally specific pattern of behavior that is associated with each sex and influences social relations, values and roles in family and society (Oakley 1972). Until recently women were locked into their socially constructed view of the world as primary care givers to their families (Burrell 1992, P. 72) and had relatively little public power, authority and influence (Black 1989). Women lacked a science and technical education, thereby forcing them to participate in the retail, food and service industries rather than manufacturing and construction, etc. This fitted in with their previous experience in the vocations of teaching, middle management, nursing and secretarial work (Hisrich and Brush 1983). Cordelia Fine (2010) believes that gender casting is a product of culture and upbringing rather than genetic inheritance. There are no major neurological differences guiding men and women’s behavior and it is nurture rather than genetic inheritance that influences skills, attributes, and personalities, beginning in their infancy and continuing through their schooling and cultural exposure within society.

Women’s motives for starting a business are very different to men. One major difference is that women are responsible for the caring of family and children, requiring flexibility and balance between their family and work responsibilities. This according to research at the time weighed very heavily on their decisions to enter into self employment (Chaganti 1986, Goffee and Scase 1983, Scott 1986). Women’s careers on the whole are characterized by interruptions due to child bearing, etc, where career is perceived as taking second place to family duties (Bruni et. al. 2004). This brings upon women feelings of guilt and stress in their careers that men do not feel (Winn 2004). This concern for balance and flexibility probably explains why businesses operated by females tended to grow slower than those operated by males (Cromie 1987).

Another important factor that the literature cited during the 1980s and 90s was the ‘glass ceiling’[4], an invisible barrier reinforced by male dominated networks, quasi male nepotism and discrimination against women’s promotions to the top managerial jobs (Bowen and Hisrich 1986). A woman’s career commitment is often treated with suspicion (Cordano et. al. 2002), thus self employment is an option for those that believe they are being discriminated against within the workplace (Cowling and Mitchell 1997). Other reasons why women become entrepreneurs through choice is independence, self fulfillment, entrepreneurial drive, and desire for wealth, power and social position (Orhan and Scott 2001). Women tend to start businesses with the ambition of making a difference, where they are more client focused, ethical in operations and orientated towards making a social contribution rather than pursuing economic rewards (Still and Timms 2000).

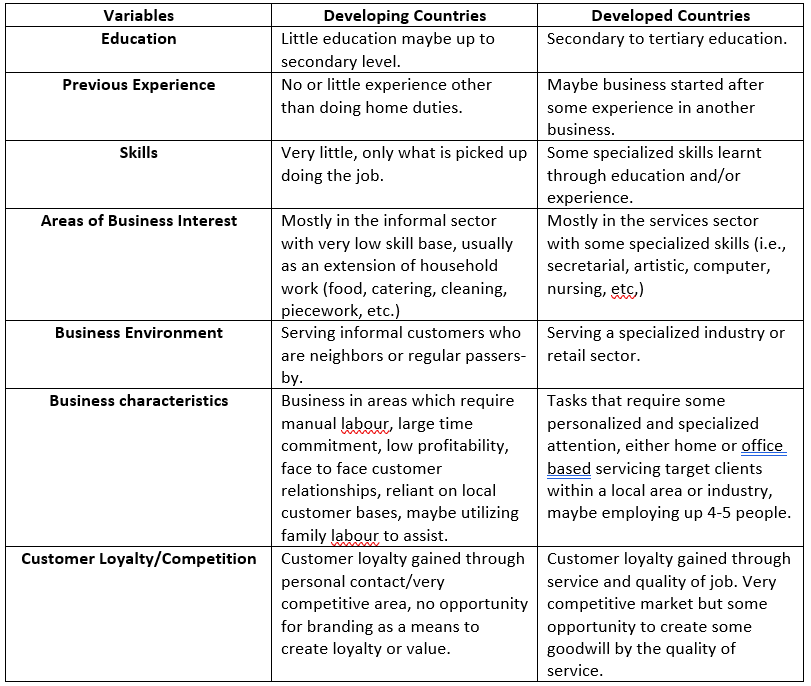

Women in developing countries have traditionally had to find ways of converting home based duties into revenue seeking activities. They tend to have very small networks and are lass able to more to different geographical location than men in search of work or opportunities (Minniti and Arenius 2003). Therefore the majority of businesses developed are low skilled, labour intensive and providing little profit. Women’s self employment activities tended to reflect their home responsibilities, i.e., child minding, home sewing and assembling, street venders, washing and ironing services, home based restaurants, and secretarial services, where face to face contact was the basis of customer relationships (Ng and Ng 2003). These micro enterprises tended to be invisible within the informal economy where the profits were used to pay for family living expenses and children’s schooling, etc (Singh et. al. 2001). Some of the traditional differences between women’s entrepreneurship in developing and developed countries is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Some of the Traditional Differences between Women Entrepreneurs in Developing and developed Countries.

Due to geographic, educational and work experience diversity today there are many categories of female entrepreneurs who engage in a diverse range of activities with a diverse range of situations. Based on the trends mentioned above a number of typologies can be outlined that may provide some better understanding of the female entrepreneurship continuum.

· The male subservient entrepreneur is a woman who is undertaking a business with their husband or partner. In this traditional dual self-employment family business, the male is usually the dominant partner making all the major decisions, controlling finance and external sales, etc. The female is usually allocated the tasks of running the shop or shop-floor in any manufacturing situation under directions of the husband partner. This is culturally the case among Southern Asian communities both in South Asia and abroad (Dhaliwal 2000). However these power dynamics vary greatly between ethnic groups, where for example women traditionally hold and control the finances in Chinese family businesses.

· The need entrepreneur is usually a single mother, widowed or divorced women who has to take up self employment to earn income to survive. Self employment is seen as a flexible alternative to salaried employment because of the flexibility it gives in caring for the children. The woman usually has a modest education and opens a home based business as an extension of her home duties, like catering, child care, housework, laundry and ironing or piecework at home, etc. These types of businesses are labour intensive, time consuming and marginally profitable, usually being the primary income for the single parent family.

· Professional women are usually highly educated (professional and/or technical) and have made a conscious decision to pursue a career as their major priority in life. They will be single, married or partnered to another highly motivated career person who has a career of their own. These women compete directly with men in the corporate world. They will stay in the corporate hierarchy until they find disappointment with inability to go any higher up the ‘corporate ladder’ due to perceived nepotism and favouritism, or other dissatisfaction with their career.

· The professional mother like the professional woman is highly motivated and ambitious but is forced to balance her working life with family life. This may have the result of preventing her to rise to a level in management in line with her true ability or potential. She may wait until her child care and other responsibilities are completed and seek to go into self employment in pursuit of some long held ambition.

· The returning professional may be the professional mother seeking a return to work after a period of absence from the workforce due to family responsibilities. Her previous dissatisfaction with the workforce or inability to get a job may influence the option of self employment. She may plan to undertake a long held ambition to develop something that she thinks is important and will ‘make a difference’, building an organization that she hopes will not only give her fulfillment but also provide satisfaction to those that she may employ. It is also likely that the firm will be ethically based trying to live up to some philosophy that she thinks is important. Her business will be client centered most probably within the service sector.