Odour is the primary feature of an essential oil when utilized as part of a product displaying a scent. Therefore odours require a standard system of classification, where those involved in the production, trade and eventual downstream product have a commonly understood method of description. A number of systems have been developed over the years by eminent perfumers. Due to the nature of our sense of smell and cognitive interpretation of an odour, each developed system is based on subjectivity, opinion and judgments. Although analytic apparatus like the electronic nose through fuzzy logic [1] can catagorise an odour [2], such techniques cannot replace the need for human input in the odour classification process because any automated measurement system would be unable to identify quality (i.e., a shared subjective opinion on what is liked or disliked in an essential oil).

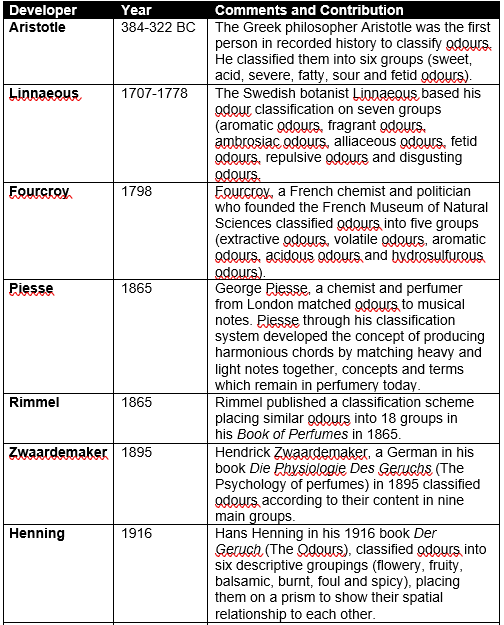

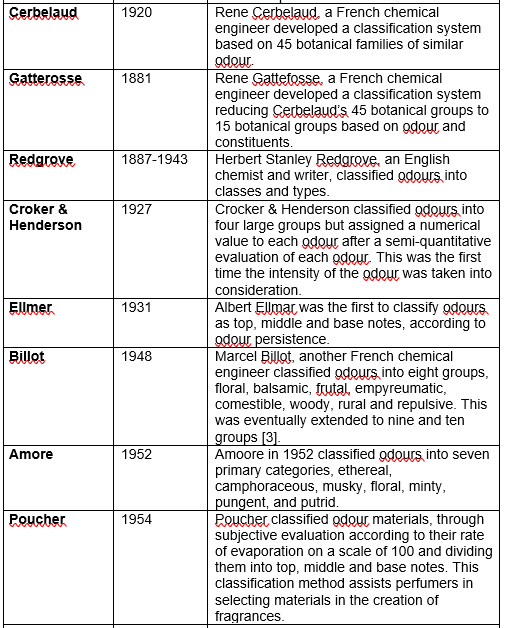

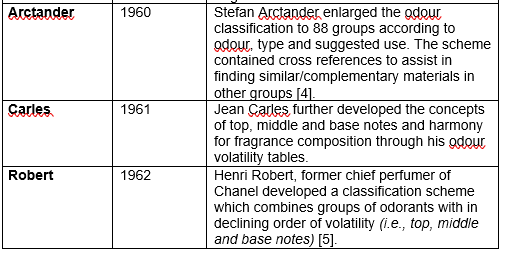

Odour classification systems have been developed over the years, utilizing groupings based on the paradigms of nature, i.e., floral, woody, fruity, herbaceous, etc. This reflects the fact that the majority of odours relate to nature and that perfumery has an artistic basis (most classification systems developed relate to essential oil application in fragrance). Some systems were developed as an odour description map, so odours could be placed in various relative categories, while others have attempted to measure odour attributes like tenacity and volatility, qualities important to a perfumer. Table 1. shows the major contributions to the evolution of odour classification.

Table 1. A Chronology of Odour Classification Systems

The difference in each classification system reflects the subjectivity and various opinions as to where odours should be placed. Some odours can be placed in more than one category, depending on the importance placed on particular odour qualities. Some classification systems have taken wide category views, while others have preferred to increase the number of categories to reflect the diversity within each general odour direction. This is why many perfumers maintain their own private systems of odour classification to suit their own purposes. There is in fact no accepted industry standard of description, although some international fragrance houses publish their own from time to time.

A number of perfume classification software packages and other forms of manuals exist. One example is Stephen Dowthwaite’s software classification system which assists perfumers to examine the odour profile of particular notes, the relative impact of the note, odour life and potential application in perfumery [6]. A slightly earlier descriptive classification system developed by Dr. Tony Curtis of the University of Plymouth Business School and the late Mr. David Williams of the Perfumery Education Centre was published in their textbook Introduction to Perfumery in 1994 [7], and used in their teaching programs [8]. Their system classifies odours into families that have features and potential applications in common, arbitrarily excluding odours like the stapelia species, where most members exude the odour of rotton fish and are repulsive. Additional modifying descriptors like light and heavy, sweet and dry are used to assist in classifying wide ranging odours in categories like floral. Curtis and Williams clearly state that their odour classification system does not attempt to create any absolute odour classification, as this would not have much benefit to the perfumer [7]. Their system is meant to be flexible to assist in developing a common descriptive language accepted by all [7] and does not define any quality of odour except for illustrative purposes [7].

Most perfumers use variations of the odour classification systems described above, modified and adjusted to suit their purposes and experience. A modified version of Curtis and Williams’ odour classification system is summarized over the next few pages [7].

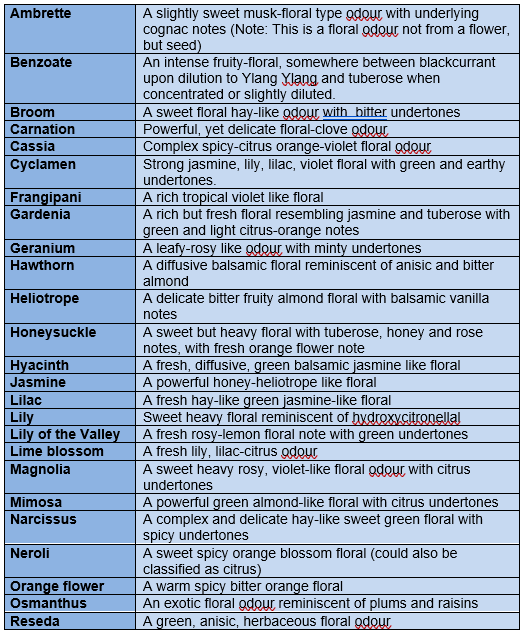

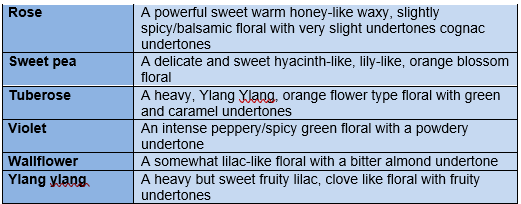

The Floral Family

The floral family is a very diverse group of odours. The one thing these odours have in common is that they come from a flower of a plant, with a few exceptions. However there are also a number of non-specific floral odours available in fine fragrance that cannot now be easily described through the nomination of a floral species. The floral group could be further divided into green, aldehydic, citrus-floral, heavy and light, etc. Some descriptions of the floral family are listed in Table 2. below.

Table 2. The Floral Family

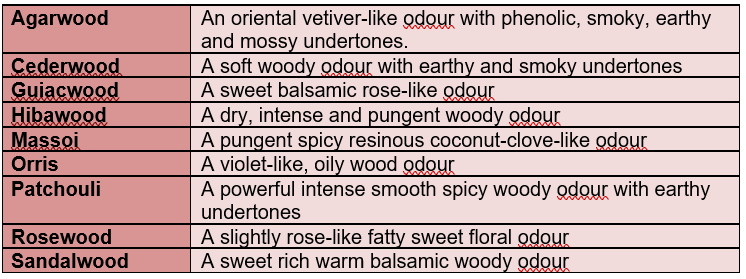

The Woody Family

The Curtis and Williams classification system defines the woody family along a triangle of three main types, East Indian Sandalwood, Japanese hibawood and rosewood, where other woody notes can be described with reference to these main notes. Patchouli and a number of other odours can also be placed in the woody family expanding its scope.

Table 3. The Woody Family

The Animalic Family

This family was originally based on the four basic aromatic extracts of animal origin which included ambergris, castoreum, civet and musk. These notes with the exception of ambergris, smell very pungently repulsive in their undiluted form. In diluted form and skillfully used, these ingredients can add warm and masculine notes to fragrances. Musk in its natural form is rarely used in perfumery today, although a number of specialty chemicals which can provide musk notes exist.

Table 4. The Animalic Family

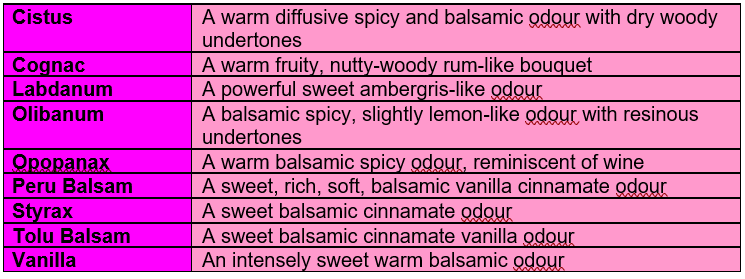

The Balsamic Family

Vanilla is a theme which runs through a large number of members in this family. These notes are usually modified which cinnamic alcohols, esters, and acids, in the case of Peru, Tolu and Styrax resins, bringing warm oriental and even woody notes. Many of these resins form base notes and blend well with members of the floral family and used in bases for floral, aldehydic and oriental perfumes.

Table 5. The Balsamic Family

The Agrestic Family

The agrestic family hosts a number of notes from the forest, jungles, meadows and soil of the earth. This is a very diverse group, even within each description as there is a range of earthy smells. For example, differences in pine and other types of forests, a number of different vegetable type odours. Another direction is oakmoss which is green, earthy and mossy.

Table 6. The Agrestic Family

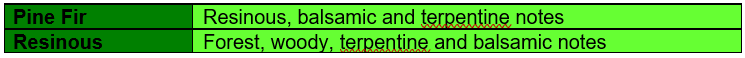

The Coniferous Family

This family includes both the pine (fir) and resinous odours that are found in forests and other natural surroundings.

Table 7. The Coniferous Family

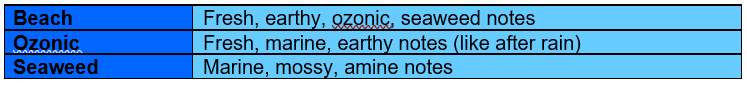

The Marine Family

A family that has grown in odour importance over the last few decades, however essential oils make little contribution, with the exception of a few (non-commercially produced) that have what one could call marine type odours. Ambergris could also be included in this family.

Table 8. The Marine Family

The Aldehydic Family

The aldehydes in this family referred to are usually the fatty and waxy type aldehydes. These are all pungent materials which only smell orangey, florally, etc., upon dilution. There are few economic sources of natural aldehydes, so most used in perfumery are of synthetic origin.

Table 9. The Aldehydic Family

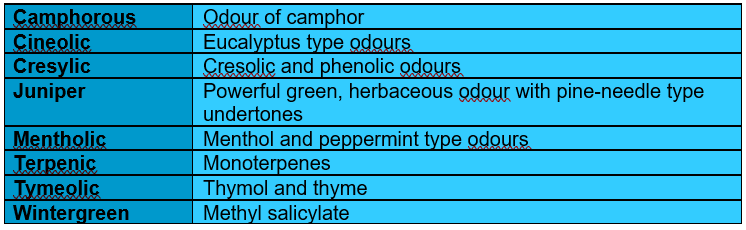

The Medicated Family

Odours in this group are usually culturally accepted odours associated with medication. These include the camphorous and wintergreen type odours in balms and the phenolic and cresylic odours of disinfectants.

Table 10. The Medicated Family

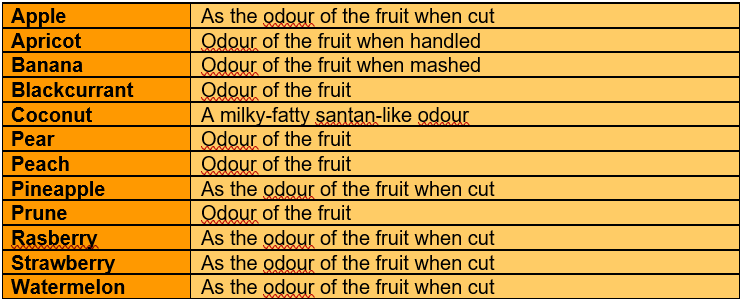

The Fruity Family

The fruity family has two distinctive branches which can be broken up into two families, fruity and citrus. Some of the odour types are well known and the fruit is just referred to in the description column. There are numerous fruits not included in this list which have distinct odours and are also in this family, particularly a number of fruits originating from the Asian region. These would include mango, guava, longan, lychee, papaya, mangosteen, starfruit, durian, tamarind and jackfruit, etc.

Table 11. The Fruity Family

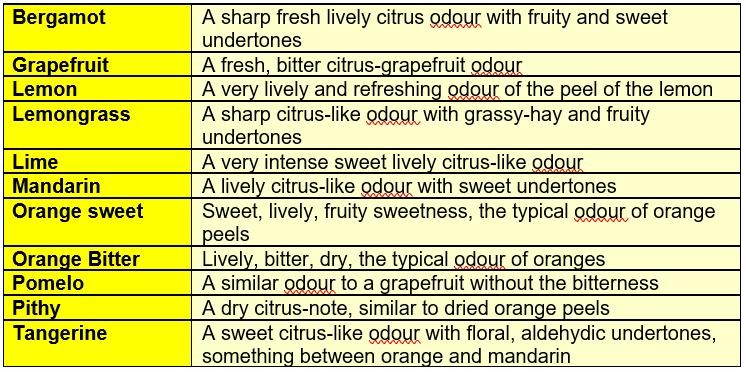

The Citrus Family

These notes are the same as the notes of freshly crushed fresh fruits (see table notes). A few citrus notes occur from non citrus fruit plants such as litsea cubeba and lemongrass.

Table 12. The Citrus Family

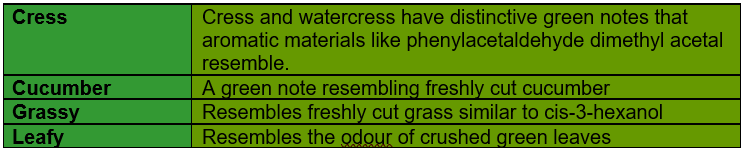

The Green Family

Green notes resemble cut grass, crushed leaves, moss, vegetables and other notes from the forest floor. Green notes are important support notes in floral, chypre, oriental and even modern citrus perfumes.

Table 13. The Green Family

The Mint Family

The mint family has the unique note diffused by peppermint and spearmint. This is primarily from the menthol content of these essential oils.

Table 14. The Mint Family

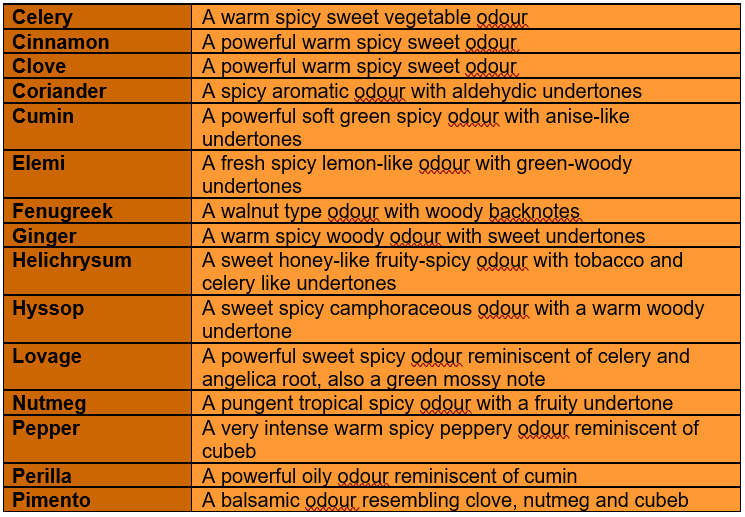

The Spicy Family

Spicy notes closely resemble the notes of their respective culinary spice preparations. Most of these notes are warm and rich and difficult to describe without reference to the original spice. This is only a representative list, as there are many other members of this family.

Table 15. The Spicy Family

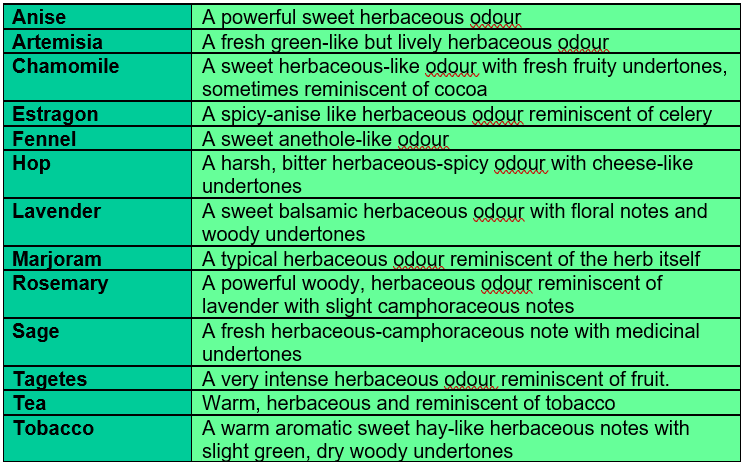

The Herbaceous Family

The herbaceous family is related to the spicy family. Most of these notes described relate to the original herb. Again this is not an inclusive list be examples of members of this family.

Table 16 The Herbaceous Family

Classifying odours was simpler before the era of synthetic materials in the 1950s. This has been made even more difficult with the advent of patented specialty chemicals. Curtis and Williams stated “that to include a ‘miscellaneous’ category in a system of classification is to acknowledge defeat in respect of those items so designated, and to establish a kind of dumping ground for the victims of one’s ignorance, wherein anything at all may be deposited” [7]. However, they go on to argue that there is such a diversity of odour qualities in a single odour profile that it would be possible to fit most odours within existing families on the basis of some selected characteristics, but this could be misleading. A number of notes that fall into this category are described in Table 17 below.

Table 17 Unclassified Odours

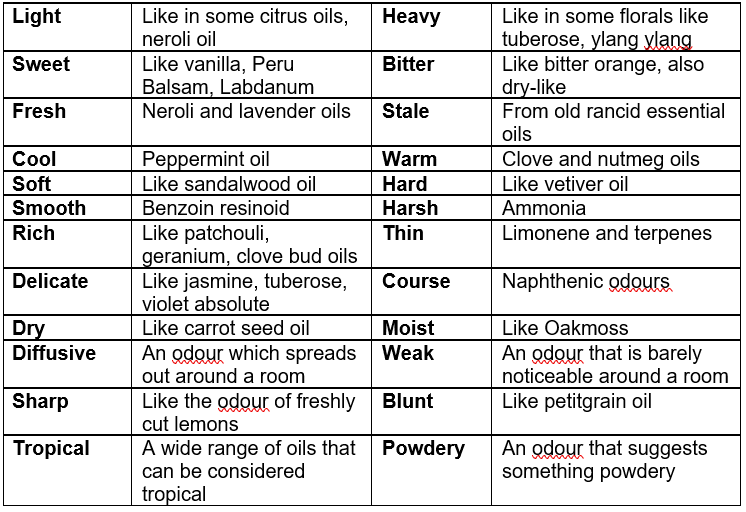

Older classification systems have used additional terms to further desribe the direction of odours. For example, Aristotle used sweet, acid, severe, fatty, sour and fetid as descriptors and fourcroy used extractive, volatile, aromatic, acidous hydrosulfurous categories to classify odours. These systems much wider in their descriptive terms capture all types of odour profiles, but at the same time are less accurate or precise in their class classification, thus rendering the system less useful to the perfumer in understanding the nature of the profile.

Terms normally used to describe other physical things can be adopted for the purpose of odour classification. Characteristic descriptors that have opposites tend to be appreciated better as the terms can be seen as being more relative with an opposite present. If these terms are learned for the purposes of odour description, then communication about an odour characteristic between two people can be commonly understood. Table 18 shows some examples of odour descriptors.

Table 18 Some Examples of Odour Descriptors

Through the use of simple charts to record impressions during an odour evaluation, a picture of the odour profile can be presented and compared with other profiles. A second chart enables the recording of a relative descriptor values by drawing a line between the opposites. Figure 1. shows how a profile for lemongrass oil could be represented pictorially.

Figure 1. A hypothetical Odour Profile for Lemongrass Oil

Originally published in Ovi Magazine, 4th May 2013

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

References

1. Dumitrescu, D., Lazzerini, B., and Marcelloni, F., (2000), A Fuzzy Hierarchical Classification System for Olfactory Analysis, Pattern Analysis & Applications, Vol. 3, No. 4, December, pp. 325-334.

2. Loutfi, A., and Coradeschi, S., (2004), Forming Odour Categories using and Electronic Nose, in Proc. Of European Conference in Artificial Intelligence (ECAI 2004), ftp://aass.oru.se/pub/ali/ECAI04.pdf, (accessed 3rd August 2008)

3. Billot, M., (1966), Composition in Perfumery, Soap, Perfum. Cosm., February 1966.

4. Arctander, S., (1960), Perfume and Flavor Materials of Natural Origin, Elizabeth, N.J., Self Published.

5. Robert, H., (1962), Quelques Reflexions sur Ia Compostion en Parfumerie, Parf. Cosm Sav.

6. See Perfumers World Website at http://www.perfumersworld.com /software/pwabc10.htm#AZtable

7. Curtis, T., and Williams, D. G., (2001), Introduction to Perfumery, Weymouth, Dorset, Micelle Press.