The Wheel of Samsara as descriptive dysfunctional organizational typologies

Seeing the organization through the Dharma paradigm

Abstract:

Organization theory has been dominated by occidental paradigms with 'Asian' philosophies making minimal contribution. This article descriptively explains the phases and realms within the Wheel of Samsara from Buddhist Dharma. These phases and realms are reframed and represented as a descriptive model of dysfunctional organizational typologies. This article is an initial step in merging oriental philosophy into organizational theory.

Keywords: Buddhism, Dharma, emotions, organization, organizational development, Oriental philosophy

1. Introduction

Unlike psychology, organizational theory is dominated by the occidental paradigm with minimal oriental thought and philosophical influence. Even the rush to understand Japanese management in the 1980s took an instrumental and positivist viewpoint, rather than a cultural and philosophical perspective, which explained the phenomenon without context. Contemporary writing on Asian organization and management is focused on the marketing, strategic, and socio-political factors, providing readers with an action orientation, without delving into too much philosophy from the region. Although we know the how, where, and why of Asian business, we have not gained very much new input or insights of new knowledge into the metaphorical sea of management philosophy. Even the rising numbers of Asian management academics residing in universities within the west take an occidental viewpoint, while Asian academics within the region import management theory rather than tap into the vast array of local philosophy that has potential applicability to organization and management.

The purpose of this article is to draw upon one aspect of Eastern philosophy and reframe it within the paradigm of organization and management. Buddhist Dharma originated on the Indian Sub-continent with the birth of Siddhartha Gautama back in the 6th century BCE. Buddhism spread through South Asia, South East Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia, taking on many forms and variations, which include the Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions. Today Buddhism directly influences about 10% of the world's population, although some practice a mix of Buddhism, and Taoism, that may even take on some Hindu influences.

Applying Buddhist philosophy to organization and management is not new. Writers have focused upon the quantum analogies of Buddhism, (1) ethics, (2) or humanist views, (3) rather than the classical context through the symbols, metaphors, and images of Siddhartha Gautama's time. The concept of Samsara was adopted into Buddhism with the metaphors of gods, afterlife, and rebirth, widely accepted during those times. The wheel of Samsara, or suffering through life is the heart of the First Noble Truth of Buddhism, that there is suffering. Although the Wheel of Samsara may appear esoteric, the messages are straight forward without the divinity of mystic gods. Much of this mysticism has been added to Buddhism through the influence of various cultures and institutionalization over time. (4)

Samsara within an organizational context can be reframed to mean a 'state of being' where the realms within the mandala refer to descriptive dysfunctional organizational typologies. The Wheel of Samsara postulates that emotions play a major role in all organizations. Contemporary organization theories have tended to ignore the role of emotion in organizations until quite recently. (5) This paper will explore the meanings contained within the Wheel of Samsara and re-present them as organizational states and dysfunctional typologies.

2. A Summary of Buddhist Dharma

A person's perception continually ebbs and flows on a daily basis with changes in intelligence, knowledge and understanding, based on the type of emotions one feels and their individual strength, pull and intensity. This process makes a person happy, sad, excited, hesitant or anxious about people, things and events around them. One may feel angry, greedy, jealous, trusting, lustful, and confused all in one day. More often than not, we are not aware of the influence of our feelings upon how we perceive things and behave, as this process is partly sub-conscious. (6) Feeling is what drives a person, whether it is to seek shelter and food, clothing and medical care, love and sex, career and comfort, etc. According to Buddhist Dharma (theology), desire is a major part of our motivation and psych.

Within the Abhidhamma Pitaka, the last of three parts to the Pali Cannon (the scriptures of Theravdda Buddhism) are a number of texts concerning psychology, philosophy and metaphysics. The Abhidhamma Pitaka describes the structure of the human mind and perception with amazing accuracy to the accepted views of modern neuro-science. The mind is described as a continual conscious process or experience in the metaphor of a 'mindstream' (something similar to phenomenological psychology). (7) Buddhism sees mankind living in a deluded reality caused by infatuation, attachment (8) and clinging to desire for objects and permanence in the world as the source of all suffering. The pathway to wisdom (9) is found through understanding 'The Four Noble Truths ' (10) and practice of the 'Eightfold Path' (11) Many of these practices are being used in modified forms for therapy today. (12)

Within Buddhist philosophy, consciousness and metaphysics are combined in the concept of Pratityasamutpada or dependent origination. This is where reality is seen as an interdependent timeless universe of interrelated cause and effect. A human's existence is interwoven with the existence of everything else and the existence of everything else is interwoven with the human's existence in a mutually interdependent way. Because this concept is past, present and future, everything in the universe is only transient and has no real individual existence.

This is a very important concept because it is only our ability to free ourselves from attachment and delusion about our sense of self and values unconsciously placed on others, will we be able to see the world as it really is, rather than what we wish it to be. In fact our view of self and existence is created through our clinging and craving which blinds us to the reality of dependent origination. (13) Buddhism is about transcending these delusions and the patterns and pathways we are locked into, so human perception is clear and unbiased. This makes Buddhism an ethical philosophy of life, rather than a religion in strict terms. (14)

3. Influence on Psychology

Since the beginning of the Twentieth Century, especially after World War II, there has been a growing interest in Eastern philosophy in the West. The teachings of the Abhidhamma Pitaka have inspired and influenced many psychoanalysts and psychologists, (15) including Carl Jung, Erich Fromm, Albert Ellis, Jon Kabat-Zinn and Marsha M. Linehan. There has been a great leap forward in humanitarian and transpersonal philosophical influence in therapy. (16) Dialogue between philosophy theorists and practitioners of East and West has led to mutually influential relationships between them. (17) This has led to new insights into therapies and new schools of thought on both sides. (18) Aspects of Buddhist Dharma are also incorporated in the works of Western philosophers including Caroline A. F. Rhys David and Alan Watts.

4. Cognition, and the Concepts of Self, Karma, and Attachment

Buddhist Dharma describes the mind as five Skandhas (layers) consisting of:

* The body including sight, hearing, taste, smell and tactile feeling (rupa),

* Sensations and feelings (vedana), (contact between the body senses and objects),

* Perceptions and ideas (samjna), (our ability to recognize objects and ideas),

* Mental acts (samskara), (willpower and attention), and

* Basic consciousness (vijnana) (19)

The last four layers make up the psych (naman). Under Mahayama, but not Theravada Buddhism there exists a 'storehouse' consciousness of inborn templates (20) designating how to perceive the world resulting from one's karmic history (bijas). Bijas combines with naman to form an ego or collective consciousness (21) creating the conscious illusions of everyday life.

The senses (eye, ear, nose, tongue and body) when see, hear, smell, taste or feel an object do so without identifying and giving any label to it. The senses collect raw data which must be identified through the process of discernment where the object's characteristics are matched against templates in the mind (memory). Once the object is identified, pleasure or pain feelings develop from the sense consciousness. This feeling then develops into like or dislike for the object which triggers feelings of desire or repulsion. Desire or repulsion varies in its intensity from a mild to a strong attraction or repulsion for the object. It is this feeling which gives any object value to a person.

Feelings can be generated from our natural condition, mental disposition, personality and training. Our natural condition is the intuitive tendency we feel whenever an object comes in contact to the senses. There will be a natural tendency to go towards or away from the object. In contrast our mental disposition is affected by our moods and can also be influenced by altered mind states like intoxication. Our life experience, environment and cultural influences all contribute the development of our personality, which also influences how we react to something. Finally through mental conditioning developed by training, we can change our programmed responses to objects. This can be seen when learning to drive a car. When just learning we need to concentrate on every action taken but once driving is conditioned within our mind, we do not require the same concentration, and actions taken appear to happen intuitively naturally.

Once we have a feeling about any object, our intention coordinates and directs the rest of the elements of our mind in respect of the object. Intention activates any action that will be taken based on the strength of our feelings. Our feelings and intention are very strongly related to our motivation. Our decision to act on anything is intention.

Our thoughts, speech and actions create karma. Karma is the law of cause and effect in relation to our mind, speech and actions, i.e., moral causation. New karma is continually generated through our 'mindstream' and is kept within us like a storage bank. Karma can be good or bad depending on the nature of the actions. Our stored karma determines how we perceive and respond to stimuli in the world. These are considered our natural or intuitive responses.

Due to the large number of stimuli within the world we live within, attention focuses our mind on specific objects in a similar way a filter takes away things that are unwanted. There are many stimuli and corresponding mental factors operating at once, however the mind is unable to process them simultaneously. In this situation only data from one sense can be processed at a time. This means for example if driving a car and speaking on a phone at the same time, stimuli from outside the car and from the phone can only be processed sequentially meaning we are experiencing an illusion that both are operating together. (22)

There are a number of higher mental processes which are sometimes present. Aspiration, similar to intention, moves a person closer to an object of attachment or away from an object of aversion. This can occur both consciously and unconsciously. Aspiration is much stronger and not always present. Aspiration is the basis for enthusiasm. Appreciation develops aspiration by signaling positive or negative qualities of the object in attention. This has the effect of directing the mind closer to or further away from the object. Appreciation also develops the feeling of desire and secures its recollection in the mind. Recollection is the ability of the mind to return to any object, and forms part of the memory. Concentration is the ability of the mind to remain focused on any object. Intelligence is the ability to examine an object and determine its value. It does this by examining an object's characteristics to determine whether it is attractive or repulsive. These decisions are made on what information the mind can retrieve about the object from memory. Therefore for the mind to carry out these functions there must be an object whether physical or imaginary.

The process of attachment begins at birth where we are quickly dependent on our mother and create likes and dislikes for things. As these emotions are so strong, the majority of people are incapable of withdrawing from these attachments in later life. (23) The thought processes that lead to attachment are important to how we identify our own sense of self and being. This is agreed upon by many psychoanalysts, including Freud, who see traits like anger, aggressiveness, craving, hatred and lust make a large contribution to how we see ourselves. (24) Attachment also gives things value or meaning, rather than the perception of the actual reality. It becomes the "lens" through which the environment is experienced and interpreted. (25)

There are different forms of attachment. (26) Sensual attachment occurs when we like processing objects that we are enchanted with. These objects include colors, shapes, sounds, odors, flavors, other objects of desire, images (whether real or imaginary) of the past, present and future that are in the mind. Sensual attachment can lead to feelings of envy, anger, arrogance, hate and can even lead to acts of murder and suicide. Everything a human does has some origin in sensual attachment and it is the power that drives people to study, work and earn money in the search of pleasure. Because of the desire to feel good, one can become a slave to another for the trappings of status, power, wealth and comforts that it brings, even though it forces one to agree all the time. Such a relationship brings out arrogance, ostentation and blind-less attachment. The desire to go to heaven preached in most religion also has its roots in sensuality. Sensuality is the primary form of attachment.

To have one's own opinions is very natural. However when ideas and opinions become cemented into a person's mind and they cling to them, this becomes attachment. Many of these opinions are bound up in customs, professions, religions, traditions and rituals and our perceptions become dogma based upon the beliefs a person subscribes to. (27) They become stubborn convictions which cannot be changed due to the cement of long held traditions, professional practices and/or beliefs. The clinging to views and opinions is based on original ignorance, where existence becomes very mechanical with programmed type responses. If we see wrong we rarely admit it, often leading to anger and even violence or war, where naive doctrines are held. When we become attached to our sheltered culture, imagination and perceptions, the potential for progress and development is hindered. When things are considered sacred and cannot be changed under any circumstances, i.e., beliefs about 'artifacts' like qualifications, 'magical processes' like strategic planning and 'secret procedures' like employee selection, rationality is distorted and becomes a barrier to change.

Finally, one can be attached to the belief of the idea of 'self' or 'I'. This is also a common occurring form of attachment and like attachment to opinion, is very hard to detect. The paradigm of 'me and mine' is based on our primal instincts to hunt and gather, procreate and protect, etc. We also tend to see our existence as eternal and fear the concept of death. This form of attachment eliminates any beliefs in transience where the person unconsciously develops delusions of permanence and solidity. This creates the fear of loss and desire to defend and protect both time and space as something needing to be held onto. Freud also saw the importance of the sense of loss to a person--love, object or experience, and saw that loss (and potential loss) can lead to manifestations of depression and anxiety. (28) This most often leads to the search for pleasure seeking experiences to avoid further pain and suffering.

Another consequence of the 'Me and I' paradigm is the development of aversion. When something threatens our self image, aversion steps in to maintain our self notion of permanence. Aversion may range from simple avoidance of the issue, to dissatisfaction, frustration or intense anger. The source of all these symptoms is our ignorance of our self at the unconscious level where the mind exaggerates the negative parts of our self image. (29) Attachment can also feel good as it may be covered in love, i.e., slave of a person, or anger with oneself may be covered with hate for something or someone external to oneself. These symptoms develop a number of defense mechanisms discussed in the next section.

5. The Wheel of Samsara

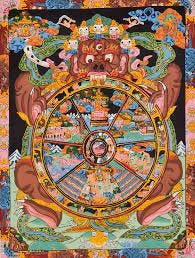

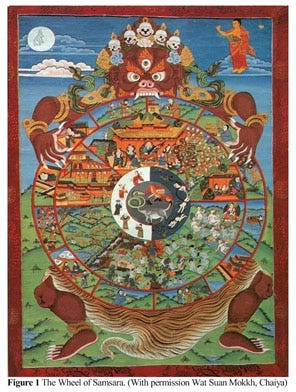

According to Buddhadasa Bhikkhu suffering arises because of unsatisfied desire and infatuation, leading to a vicious cycle. (30) This is known as the Wheel of Samsara which pictorially depicts the endless cycle of suffering continually flowing through our life in the past, present and future, leading to endless births, deaths and rebirths through various realms (mind-states) for all forms of life.

Central to the Wheel of Samsara is the concept of Paticcasamuppada or dependent origination which is a perception state based on ignorance. Through sensual (eye, nose, ear, tongue, body or mind) contact with something, feelings are derived. This is because of our notion of self ("I and mine") and desire, always bringing suffering through feelings, attachment and clinging. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu gives numerous examples of dependent origination like when a baby is upset when her doll is broken, a boy fails an exam and ends up fainting or crying, a girl sees her boyfriend walking with another girl and becomes inflamed and furious and people become attached to foods they like. (31) In each case Buddhadasa explains that the sensual consciousness is aroused giving rise to feelings, bringing a conditioned response based on ignorance, triggered by one or more of the types of desire, discussed above.

Dependent origination occurs within the context of flowing through a number of states of ignorance and types of attachment, being continually re-birthed within one of the realms (mind-states). Thus living things are just transient beings through each realm (mind-state), which infers that the perception of an independent self life existence is an illusion. The Twelve dependent origination links, which resemble a person's thought processes on the outer part of the Wheel of Samsara are explained below:

Ignorance is the first of twelve situations in dependent origination. A blind woman who is about to fall over a cliff is metaphorically depicted. This shows that a person with a mind deluded in ignorance will stumble through rebirth, after rebirth ignorant of what really constitutes her individual existence and reason for her suffering. Therefore unable to break the cycle of samsara.

Karma or action is the second link where we shape our lives by the actions we take. This is symbolically depicted by the potter creating pots. Good karma leads to our transition to the higher realms (mind-state) and bad karma leads us to the lower realms. Ignorance leads to being imprisoned within the cycle of samsara.

Consciousness of mind is the third link, usually depicted by a swinging monkey representing how our mind moves from object to object through boredom without examining oneself. This is confused and ignorant consciousness where understanding of the concept of non-permanence is impossible. If the consciousness cannot be transformed from ignorance to enlightenment, then the person will continue going around the cycle of samsara.

Name and form make up the forth link referring to the five forms that constitute a person, physical being (the senses), contact with objects, perception, mental labeling and consciousness. If our consciousness still retains some ignorance before death then the forth form will go to the intermediate period between death and rebirth. This is depicted by a man rowing a boat halfway across a river, yet to reach the other side.

The five senses are the fifth link following on from the last link where a person is about to undergo rebirth. The five senses, sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch are physically formed in the mother's womb but yet to have the power of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch because as depicted in the picture, the house is still empty.

Contact is the sixth link which is the point where the senses make contact with an object but are yet to form any reaction to the contact. This is usually depicted by two embracing lovers.

Perception is the seventh link where contact with an object gives a basic intuitive feeling of pain or pleasure. This stimulus is not felt as something liked or disliked at the perception stage. The power of perception is usually depicted in the cycle of samsara as a man with an arrow through his head.

Attachment is the eighth link. A person begins to mentally label perceptions as good or bad according to our self-centered desires and aversions. This attachment builds our desires, contributing to our suffering. The person addicted to alcohol in the cycle of samsara is symbolic of the attachments we create.

Craving is the ninth link, which is more intense form of attachment. People are not content with what they have and desire to seek pleasure and avoid pain, even at the cost of harm to others. This is intensely selfish and leads to bad karma which traps one to going around the cycle of samsara. This is depicted by a monkey reaching out on a tree for more fruit.

Another birth within samsara is the tenth link. A person with a life of craving through ignorance will be doomed to be re-birthed within the cycle of samsara. This is depicted by the pregnant woman.

Existence is the eleventh link where the woman has already given birth. The karma from selfish attachment and craving of the last life has caused an existence within the cycle of samsara in the next life.

Death is the final link in the cycle of samsara. If death occurs with any semblance of ignorance in the mind, then birth will occur again and again in the cycle of samsara until it can be broken through an understanding of dependent origination. This is depicted in a picture of a person taking a corpse out for burial.

The links in the cycle of Paticcasamuppada (dependent origination) are states conditioned by the previous link and go onto condition the following link. Through ignorance there is karma that creates a conditioned consciousness of despair. The physical senses condition the mind consciousness through perception, creating feelings that trigger attachment and craving. This escalates into clinging which conditions karma, the force which determines which realm (mind-state) the person will enter into at rebirth, continuing the cycle of samsara. This links the past, the present and the future.

The six realms (5 in Theravada Buddhism) inside the links of Paticcasamuppada can be seen as metaphors for various 'mind-states' one experiences during life. (32) The depicted realms can be correlated to psychotic pathologies. (33) Existence in each realm creates a different sense of self, (34) reflecting distorted views of their own ego, (35) leading to certain types of behavior. Unless one can break free of their karma, one is trapped into moving between these different realms or 'mind-states'. Ones actions of body, speech and mind extend beyond the present life will determine what realm one will be re-birthed into in the next life. Each realm has particular advantages and disadvantages for obtaining enlightenment.

The Realm of the Deva (gods) is a world where the Deva have great power, are very wealthy, have a long life and are relieved of all forms of suffering. They have got to this realm because of amassing lots of good karma. The Deva are complacent and therefore blind to the suffering of others and cannot learn compassion and wisdom. During their long life in this realm they use up all their good karma and are re-birthed in lower realm in the next life as they are still tempted by sensual pleasures and distracted from meditation. In Theravada Buddhism the Deva share a realm with the Asura. The Asura are depicted in the Wheel of Samsara as gods with access to the wishing tree and are waging war with the Devas for control of the tree. The white Buddha is playing the vena to remind the gods that their time in this realm is only temporary.

The Realm of the Asura is a world of envy, jealousy and hate. The Asura have the same comforts as the Deva. They have gotten into this realm because they had good intentions but committed bad acts, most likely harming others. They have enough good karma to get into the Asura realm above the lower worlds but their hate and jealousy prevents them from entering the realm of the Devas. The Asura see themselves are superior to all others with no patience for inferiors and usually look down and belittle others. Outwardly they show themselves pious, wise, just and fair, devoted to worship. The Asura are mortal enemies of the Deva and are fighting a continual feudal war over the wishing tree. The roots of the wishing tree are in the realm of the Asura but the wishing fruit only grows in the realm of the Deva. The Buddha depicted in the realm is holding an arrow and preaching moral restraint.

The Manusya or the Human realm is based on passion, doubt, desire and pride, all qualities of human existence. This realm is the most advantageous and most precious, as there are fewer humans than other creatures, except for Devas. Only humans have the wisdom to practice Buddhism. Therefore the human realm is the only realm where one can obtain enlightenment because humans have much more potential when life is pursued correctly. However most people waste their lives in the pursuit of material objects which end up reinforcing attachment, craving and clinging. Therefore most descend to a lower realm in rebirth. The scene depicts Buddha teaching the benefits of mental discipline and The Four Noble Truths to his disciples.

The Naraka or Hell Realm is the most terrible of all the realms containing a number of cold and hot hells. People are rebirthed into the Hell realm because of burning hatred, coldhearted cruelty and aggression. People remain in the hell realm until all their bad karma is extinguished and they are propelled into another realm. The lord of death is depicted in the top right hand corner of the realm where he holds a mirror so people can see their own bad karma. One the top right hand side is a Buddha holding water to signify patience and a flame as the light of hope.

The Tiryagyoni or Animal Realm is a world based on stupidity, prejudice, complacency with little intelligence. People who are ignorant, act upon primal motivations without any moral reflection and contented are destined for rebirth in the Animal Realm. Within the realm one lives a sheltered life of slavery trying to avoid discomforts. As animals cannot reason they are incapable of learning Buddhism and will stay there for many rebirths. The Buddha is depicted in this realm as holding a Dharma scroll to show the benefit of perfect wisdom and ethical conduct.

The Realm of the Preta or Hungry Ghosts is where people have an insatiable hunger and craving which cannot be satisfied. A hungry ghost is always looking outside himself for new things that will satisfy his hungry and craving. People are rebirthed into this realm because they are addicted to something, obsessed, compulsive or possessive in their previous lives. The hungry ghosts are depicted as beings with big empty stomachs, long necks that cannot shallow and a pinhole mouth, so their desires will always torment them. They have fire coming out of their mouths because their cravings cannot be satisfied. A Buddha is seen carrying a container of nourishment to sooth their pain.

The black and white circle inside the realms shows that karma drives people around the realms. The white side shows ascension into the higher realms of the Asura, Manusya and Deva, while the black side shows the dissension into the lower Tiryagyoni, Preta and Naraka realms. The very centre of the Wheel of Samsara shows the three poisons we develop from birth. The snake shows anger which is very powerful as it can destroy previously collected good karma. The Rooster represents high sexual drive and the pig represents ignorance. These three animals are shown chasing each other because each poison reinforces the other two. This is the reason why people keep having rebirths within the wheel of samsara.

The Wheel of Samsara is held by the demon Yama who depicts death and suffering as an inevitable fate within samsara. One is encouraged to forsake attachment for the pleasures of wealth, material things, beauty, youth and reputation that hinder an enlightened mind free of anger, greed and ignorance. The Buddha on the top right hand side points to the moon which represents The Third Noble Truth, the cessation of desire, i.e., there is a way to end suffering and escape samsara.

Although the Wheel of Samsara specifically refers to individual delusion, analogies can be drawn out to organizations. The physicist David Bohm conceptualized consciousness as a collective stream of thought where meaning is developed through language and individuals make sense of it. (36) As a 'collective consciousness' where individuals share the assumptions, beliefs and values of the group, an organization can also be seen as being trapped within the Wheel of Samsara, unable to see though its collective delusions. The 'collective consciousness' of the organization would hold views about how much the organization can influence the environment it operates within, the nature and strength of their own competencies, how competitors will react to their actions, how consumers think, how employees are motivated and what constitutes an opportunity to the organization.

6. A Model of Organization States and Typologies

The Wheel of Samsara can be construed as an interrelated time phased model representing the past, present, and future of an organization. Past, present, and future are linked through the notion of identity made up of vision, mission, objectives, strategies, procedures, structure, products, artifacts, people, culture, and symbols, i.e., what an organization has done in the past determines the present and future state of becoming. Thus an organization's becoming is a result of the actions it takes within both the organization and environment, according to the doctrine of dependent origination discussed previously. This is represented by various states around twelve outer circles that provide an interrelationship between the organization and the environ ment. This means that all perceptions of reality are actually a construction of an organization's biases determined by the prevailing shared emotions of the people within the organization, manifested as values, beliefs, assumptions, past experiences, future aspirations, and perception of the organization's capabilities and ability to control external events

The twelve elements of dependent origination can be viewed as stages of the organization lifecycle, where at certain times particular choices are relevant to the future trajectory or path of the organization, i.e., decisions about taking which crossroad an organization must make from time to time.

The first phase is ignorance correlating to the start-up stage of an organization. This is a time where there is little knowledge about the opportunity and environment, and great uncertainty. Visions and objectives are vague and still forming. The environment is still deeply mysterious as the members of the organization are yet to gain any direct experience and feeling from working within it. Nothing can be quantified. Decisions and actions taken this time will create a path which will act as a channel from where subsequent future decisions will be made. This will primarily occur through effectuation, where possibilities that have potential will be considered and evaluated without preconception, something akin to a painter sitting in front of a blank canvass thinking about what to paint. (37) Beliefs may still be fluid and based upon guessing at this stage of immaturity.

During the ignorance phase values and beliefs begin to develop as experience and feeling is gained, and these begin to become embedded within the organization to become guiding principles of decision making in the future. These initial values and beliefs may be very effective at this stage, but later may become impediments to change in the future if these values and beliefs fail to maintain relevance to the dynamics of the environment. This could 'blind' an organization to potential threats and opportunities. Some extreme forms of behavior are beneficial at this time. For example, some paranoia may lead to close scrutiny of the environment, compulsiveness will bring a heavy action orientation, and control of decision making which helps to implant a firm vision and direction for the organization initially. However these qualities which may be instrumental in establishing the organization successfully may become rigidities that inhibit change and the ability of the organization to adapt in the future later on.

The second phase is the karma stage where the organization's trajectory is established. Form and action is the result of guiding aspiration. All action taken will be in the form of products, services, strategies, policies, procedures, and structures. Karma is therefore being and the resulting consequences of both external and internal organization action. Karma carries the seeds from the start up phase, heavily influenced by the values and beliefs of the founder who may or may not be able to release reigns of control of the organization, once it has outgrown the simple organizational structure. This may result in chronic rigidity and lack of creativity within the organization in the future. The very identity of an organization itself can become rigidity in practice, i.e., the firm's mission is rigid and nothing outside of this mission is accepted as a probable trajectory. Karma is the result of all previous actions, the history embedded in beliefs and consequences, manifesting in both culture and outcome. Karma has deep ethical implications. Ethical behavior is more complex than following codes, the (unintended potential consequences of actions require reflection. Ethical behavior requires creativity to develop actions with outcomes free of undesirable consequences. The actions of Enron in covering up accountancy discrepancies started small but compounded to the point where the corporation and the Accounting giant Arthur Anderson also went into bankruptcy over the matter. Poor ethical behavior is an end game. The concept of karma indicates the need for long term wisdom with an organization.

The third phase is consciousness, the ability to perceive the environment and derive meaning. Early perceptions at the ignorance phase contributed to forming the early visions and objectives of the organization and have become dogma. This dogma also represents the identity of the organization. The associated beliefs and emotions determine the conscious sensitivity of the organization. This is the guiding force behind all perception, action, and behavior. Resulting brands, strategies, and structures have developed a persona that the organization exists within, members believing that these are the 'magical' recipe of success. There becomes a sense of permanency, a belief that the present will exist forever. However permanency doesn't exist, which is a deluded reality, and becomes a barrier to adaptation and change. As a consequence the organization becomes locked into these processes and actions, where complacency develops, and people are satisfied and wish to 'rest on their laurels'. The organization loses its entrepreneurial flexibility and starts becoming rigid. Leaders begin to believe they know all that there is to know and cease to scan the environment for opportunities and threats, becoming 'blind'. Sometimes this overconfidence brings arrogance. A culture of 'false urgency' may develop where the organization is busy undertaking tasks for things that important to the firm's progress or survival, (38) and 'pseudowork', following rules rather than striving to achieve goals, (39) a belief in the process rather than the ends.

The consciousness phase sets up the name and form phase where the organization's identity is clearly established through products, people, strategies, and systems, etc. The organization's culture and trajectory are well engraved, and serves as the platform from which the future will emerge. As a consequence information that threatens the organization's self image is either ignored or passed over. In addition, the organization exists within an atmosphere of anxiety and fear of loss of what has been achieved. Thus the organization is huddled in frustration, confusion, avoidance, and delusion of the truth, where this is countered and suppressed through stability and rigidity. The organizational culture is conservative and averse to risk taking. Change is hindered by this fear of taking risks and thus creativity, innovation, and motivation is on the wane. This clinging to the desire of permanence leads to ignorance of the realities within the environment, leaving the organization susceptible to competition from other organizations. This can be clearly seen in the bankruptcy of Bethlehem Steel Corporation that failed to deal with internal employee superannuation issues and the advance of overseas competition, new technologies, and business models in the industry that were more cost effective. Examination of the '500 lists' indicates that this is a very common occurrence. (40)

The senses phase is about the ability of the organization to adapt to changing environmental conditions. Any organization' survival depends upon the ability to adapt and to relevantly redefine itself according to the new conditions within the environment. However most firms are trapped in the patterning of the name and form phase, blind or complacent to environmental dynamics. Moving to the next phase requires an organization to not be burdened by its own history and rigidity. This phase recognizes that the lifecycle of organizations is a finite one, and most firms succumb to the mythology of their own successes, and may not be able to enter into the contact phase, instead moving directly to the death phase. Without adaptation there can be no rebirth of the organization where it will eventually become irrelevant to the environment.

The contact phase represents awareness of potential opportunities and issues within the environment and organization. However any reaction to these opportunities and issues will depend upon the organization's fluidity to act. An organization can only reach this phase if it has a certain degree of sensitivity to the environment, which doesn't exist in all organizations. Failure to have the sensitivity to see opportunities and issues prevents the organization developing through growth and change.

The perception phase is where the organization gives meaning and weight to what it observes in the environment. Unlike what we are led to believe through the mythology of management science, this is not done by analysis but through intuitive thinking, influenced by our vision, interests, and emotions. Positive memories and emotions will facilitate a favorable consideration, while negative memories and emotions will facilitate unfavorable considerations. Emotions can set an organization into a habitual way of perceiving the environment and delusion of rationality. The organization may become self-absorbed theorizing the successes or failures of the past and excessively moralize on future actions, until they have convinced themselves against taking action. Rationalization becomes a hindrance to action. This is a very important phase as it provides an option for the organization to continue on current trajectories or change actions that may take the organization on new trajectories, if the organization chooses to pursue new opportunities. This phase is also important to the ethical path an organization takes, as decisions made are conscious ones with knowledge of the potential consequences of action.

The next two phases are attachment and craving. Attachment recognizes that decisions are based upon biases. Most decision making will be based on either, the hopes and aspirations of future outcomes, or beliefs about successes and failures of the past. This phase can block the organization's ability to adapt. The craving phase is an escalation of the attachment phase where the organization makes decisions purely in self interest without concern for other stakeholders or outside entities. This leads to poor ethical decisions which will have future destructive consequences. This may also be a period of great wastage and excess for the organization, which will lead to inefficiency and un-competitiveness.

The rebirth phase reminds us that history is always repeated unless we are able to learn from our mistakes and develop the organization. This is a strong inference that learning within an organizational context is paramount to the ability to adapt.

The existence phase recognizes that the trajectory of any organization is dependent upon the skills, talents, competencies, capabilities, and past experiences of the people who have created the organization. These qualities and the subsequent actions will determine the future state of the organization.

The final phase death is where all organizations eventually end up, especially if it doesn't change according to the needs of the environment. This resembles the concept of creative destruction postulated by Schumpeter, where new innovative products render existing products obsolete in the marketplace. (41) The only way to avoid the death phase is to maintain and innovative stance at the product level and be adaptive at the organization level.

The above phases discussed represent the 'cognitive processes' of an organization within the organization lifecycle. Emotion influences our perceptions, cognitive processes, evaluations, motivations, and decision making within organizations. This affects the way we see opportunity, our responses, what we pay attention to, the types of biases that influence our thought processes, positive and negative motivations, and post decision emotions. (42) Survival and outcome is entangled within perception, action, and the concept of dependent origination.

The Wheel of Samsara also provides six realms, 'state of minds', or typologies that an organization exists within. Each leads to a different sense of identity that will influence awareness, assumptions, attitudes, beliefs, values, culture, views of the world, decision making, and types of strategies employed. A realm is a collective 'psych' or 'ego' of an organization. Organizations are locked into a specific realm which they have difficulty escaping. Each realm is briefly described below.

The realm of the Deva contains organizations that have been successful in the past, but have become complacent and blind to the present dynamics of the environment. As a consequence the organization has become very bureaucratic, rule orientated, and hierarchical. Due to past success, the organization follows established strategies with little concern for what is going on in the market place. Managers work for status and personal gain within this organization. The organization has become righteous, proud with a feeling of superiority, bordering on the arrogant, with a need to glorify itself. Identity is more important than performance. Management makes stereotyped and biased judgments about people, competitors, and events and cannot accept dissenting views or opinions contrary to shared beliefs. The socialization forces are so strong that it is difficult for anybody to free themselves from the prevailing 'ways of doing things'.

The Deva organization has developed many sophisticated coping mechanisms to deal with any information that does not fit into its view of the world. Any shock may result in acts of denial just like the US steel industry claimed the Japanese were dumping steel in the US market when they could not compete in the 1980s. However this type of shock can weaken an organizations perception of its self identity where it may take on depressive tendencies. (43) The organization may develop a sense of hopelessness, inaction, and pessimism, and rely on ever increasing conservatism to cover feelings of fear and anxiety. Any incoming information will be negatively construed with a sense of powerlessness over the environment. This may be the time the organization seeks a savior or messiah to free it from all its problems. This typology is very common with large established firms in stable markets where product processes are fully automated. Examples of these types of industries would include the steel, automotive (prior to 1980), agriculture, construction, transport, and chemical industries. Industries that have been protected by tariffs and formed oligopolies would also fit into this realm. Firms in the Deva realm are open to takeover by stronger and more ambitious competitors. For example, CEMEX the Mexican cement giant took the opportunity to takeover many companies in South-east Asia during the 1997-1999 Asian financial Crisis.

The realm of the Azura fits aggressive, but sometimes overstretched organizations. These organizations have generally good intentions but act ruthlessly in the market which often leads to negative consequences. For example both John D. Rockefeller and Bill Gates were criticized for acting ruthlessly during their business careers but became major philanthropists, upon their retirement. Organizations within the Azura realm like to be seen as pious, but inside they feel superior, look down on others, and tend to favor win-lose strategy scenarios, with the objectives of becoming the dominant firm in their chosen industry. In this quest they may begin to become slightly paranoid and suspicious of competitors, and thus vigilantly scanning the market, keeping the organization on a 'war footing', ready to defend itself against any onslaught by a competitor. Consequently the organization spends a lot of time and effort collecting information to look for any evidence to confirm suspicions. This is based on an intense fear and lack of trust of others and may also reflect upon the way the organization is centrally run.

The Azura realm may also include organizations that are on 'evangelistic missions' which is an extremely powerful motivation to its members. This can also lead to compulsive and dramatic tendencies, especially when the organization wants to draw attention to itself. On the positive side, the Azura realm may suit organizations in extremely dynamic environments where rapid change is occurring.

The Manusya or human realm is a paradoxical one, full of emotions of hope, passion, the desire to achieve, yet also harbor feelings of anxiety, self doubt, low self efficacy, and frustration if things go wrong. This is the realm where aspirations and intentions are high which have the potential to bring high ethical standards to the organization concerned, but at the same time it is also very easy for the organization to fall into one of the other realms, if it is not careful. The manusya organization has high ideals but, but it can get entangled in the processes trying to get there very easily, making the organization ineffective. Such organizations are capable of getting involved in causes greater than themselves.

Many firms start out this way but discover the paradox of keeping principles and being practical to difficult and succumb to the economic pressures to err on the practical side, dragging the organization down from its high moral position. Such firms may experiment with decentralization of decision making, empowerment of its membership, and seek consensus rather than top-down directives. Members within these forms of organizations are able to take a step back and say 'I don't know how to do this but it is a good opportunity to learn something'. They possess the qualities of fairness, are not prejudiced by stereotypes, or look at things superficially. They may also have a sense of non-conformity, which may be reflected in strategy, where diversity is celebrated and appreciated within the organization. Whether this all works is a matter of finding out through experience. These experiences will either reinforce the experiment, or cause the utopian ideals to be abandoned in favor of more traditional management practices. Such organization types are suitable for highly technical tasks requiring trans-disciplinary approaches like research and development and other highly creative or artistic tasks.

The Naraka or hell realm is the domain of low self efficacy, decline, and failure. There is an underlying current of depression within the organization characterized by feelings of hopelessness and little control over the environment. Management is generally pessimistic looking at anything in the worst possible light. Other cognitive distortions include arbitrary inferences (jumping to negative conclusions about everything), personalizing (assuming everything is one's own fault), and castastrophizing (thinking of the worst case scenario about everything) will distort incoming information, leading to the feeling of being a total failure, where a self fulfilling prophecy develops. (44)

Within the organizational context, there will not be much interest in anything, leading to a number of stifling consequences such as failure to replace assets, little, if any new product development, little market intelligence gathering, poor customer service, and leadership indecisiveness. There will be a basic pessimistic outlook towards the outside environment. The organization will tend to be very bureaucratic and hierarchical, the same it has been for decades (if it is an established company). Managers will not take any initiatives and leave major decisions for the board and committees to make. The organization operates through procedures with little impact for what is happening in the marketplace. This brings complacency, developing strong barriers to any form of change. Strategy tends to develop from within, rather than from the market as managers feel they already understand the market well enough and there is no need to do any further field analysis. The competition is seen as homogenous and too much field analysis could bring uncertainty, shock, and anxiety about the need to change which is what the organization is trying to avoid. Organizations within this realm would include those within declining industries, utilizing old technologies, where no vision exists.

The Triyangyoni or animal realm comprises organizations that are basically short-term, rent seeking, non-innovative, and tend to follow other firms in their industries. The organization is orientated strictly towards short-term gain, profit orientated, often at great long term cost. This short term orientation heavily influences products, strategies, customer service, and employee policies, etc. As a consequence such organizations have little interest in investing in the future. The market is rarely scanned for information, and most issues thought about are now and immediate. Decision making is very emotional, focused on short-term gain, and often very unreflective, bordering on being impulsive. The organization is incapable of learning from errors and mistakes to improve itself, and can only copy other organizations as a means of adapting to the environment. Narcissistic behavior is also common, where there is bullying, manipulation, and deception used as tools of internal control and domination. Subordinates usually see through the insincerity and become de-motivated, uninspired, skeptical, and stop giving creative suggestions to the leaders. Most management posts are filled through politics and nepotism. Members that have influence are those favored by the leader. The leader sees employees only as tools to implement his or her plans. The views of subordinates are rarely taken into account for decisions. Such organizations exist in trading, production orientated, contract manufacturing industries, sometimes termed as the 'sweatshops' of Asia. These organizations can also exist in low technology industries where little market leadership can be achieved and no one firm can dominate the market like construction, real estate, some retail, and other short term orientated ventures.

The realm of the Preta or hungry ghosts is usually where very ambitious organizations exist. They tend to be high growth organizations that are highly profit orientated. These organizations may often be trend setters and leaders in their industries. The organization may have an almost compulsive culture about it with a sense of urgency. However this sense of urgency can be negative and cut across efficiencies. Decisive strategies are set but can very quickly change where new opportunities come across the horizon, in the quest for profit. This makes it difficult to develop really long term strategies, as the organization is dominated by opportunism. The leader will put a great emphasis on control and often be stubborn, unable to delegate to others in fear of missing opportunities. Conglomerates may fit into this category where the organization may grow through acquisition of smaller firms to take advantage of opportunities. Other organizations in this category may include banks, insurance, and other financial service providers.

The black and white centre circle represents the basic paradoxes the organization faces. How we see these paradoxes influences the ability of an organization to change. Ethics and profits can be seen as conflicting objectives, just as cost and profit, individual verses society interest, knowing when to be diplomatic verses being honest, personal loyalty verses responsibility for what is right, and considering the short verses the long term, etc. For example, if one believes employees can't be trusted, then it is most likely organizational policies will be designed around this belief, which will suppress creativity and innovation. Paradoxes usually block the way to a new future. If an organization is locked into a paradox then it is doomed to continue within the scenario of Samsara. It is only if an organization is able to develop a mutually related coexisting relationship between the dualities of the paradox, will it be able to adapt and develop. Paradoxes influence our level of awareness and are very difficult to overcome as they are deeply embedded within our assumptions. The snake, rooster, and pig in the very centre represent our basic organization physical, emotional, and intellectual energies and drive.

The demon Yama holding the wheel represents the ambiguity, uncertainty, and complexity of the environment. Only by being comfortable with the environment will one be able to see opportunities and be able to innovate and progress.

The Buddha outside the top right hand side of the wheel as we look at it represents the tools to escape Samara through the cessation of desire, the third Noble truth. The tool for this is the Eightfold path consisting of right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, mindfulness and right concentration. As this paper is primarily concerned with reframing the Wheel of Samsara as a descriptive dysfunctional typology map of organizations, laying out the strategies is beyond intended scope of the author. However many other authors have been influenced in their writing by the Eightfold path, particularly those writing about learning organizations. Most of these tools are regularly utilized in corporate and organizational develop workshops concerning change and transition.

7. Conclusion

It should be noted that contemporary Buddhism is taking a more liberal view of attachment/detachment. (45) Some detachment could actually be apathy towards anything and everything by a person. Detachment itself can be a sign of the inability of a person to handle life situations, for example use detachment as a defense mechanism to cope with distress; such as a child coping with the distress of the absence of a parent. (46) This can possibly leave unresolved issues between the child and parent, which can be considered unhealthy and detrimental to emotional growth and learning. There is a difficulty of distinguishing apathy from the type of detachment that liberates the consciousness. Therefore a possible reason for and effect of detachment, is people become apathetic losing any care about the world and being unhappy.

There can be distinctions made between desires that are unwholesome like greed and desires that are consistent with Buddhist practice like the desires for auspicious virtues. This also implies some distinction could be made between 'positive' and 'negative' desires. (47) The test here is whether any desires emotions or thoughts are ego-centric or not? (48) Even the desire to do virtuous things can be ego-centric in nature.

Thich Nhat Hanh stated that every feeling whether good or bad, powerful or light should be paid attention to with mindfulness (49) that can be used as a force to protect the psych. (50) This has two important implications. The first is to be aware of our own biases and distortive tendencies in our perception of objects. The second implication is that we protect ourselves from harmful influences and 'emotionally' learn. Psychotherapy advocates a healthy ego which requires some 'healthy attachment' like identification in the creation of a sense of self (51) Das expands on identity as being something we experience spiritually, sexually, sensually, intellectually, economically, philosophically, and so on. Identity is situationally dependent upon the role one plays as a mother, father, worker, student, etc. (52) However from the Buddhist perspective, this can lead to an ego produced out of mistaken identity, based on anxiety and confusion about 'who I am '. (53)

John Bowlby's seminal work on attachment theory defines attachment as one of the prime motivational systems with its own workings and interfaces with other motivational systems. (54) What may be important is understanding desire as a driver of motivation. (55) Thus some attachment is considered to be a healthy part of a person's psychological make-up, a driver for action. However it should be noted that the motivation behind our actions is usually desire, which unchecked can develop into many abnormal pathologies like depression, anxiety, aggression, etc. (56) It is not the desire that causes the suffering, but what we do with our desire. People need to feel secure and have loving relationships to provide a base for life exploration, which requires some attachment. Michael Porter also recognized that emotional attachment can influence rationality of strategic decision making where one may be committed to a business, have a sense of pride, be concerned about the stigma attached to a decision, identify with the program or venture, etc. (57)

A true understanding of the concept of attachment and detachment from the Buddhist perspective may have been lost in the semantics of translation, especially with the institutionalization of most of Buddhism's doctrinal interpretations. Modern Buddhist and psychology scholars with the benefit of hindsight have added new perspectives by taking more liberal semantic interpretations of translations providing new insights. (58)

Dharma seeks to make us aware of the emotions one is attached and clinging to so that we can be freed from the suffering it produces. We make sense of the world we see through the filters of our own attachments which distort reality. Griffiths used a very useful metaphor of a mirror that cannot reflect light because of dust that has settled upon the surface clouding any clear view. (59) So Buddhism and psychoanalytic-theory may assist in helping one see the manifestations of attachment and their underlying causes. The task is to let go of the distortions of perception created through sub-conscious attachments. This means understanding illusion from biased judgments, aversion, prejudice and greed in us and seeing the environment for what it really is. Buddhist Psychology provides a non-linear model for seeing a non-linear world. According to Freud, one is "in danger of never finding anything but what he already knows: and if he follows his inclinations he will certainly falsify what he may perceive." (60)

We in adulthood have become a product of our own eyes, prisoners of our own mind, observing things with a construed reality. (61) Our attachment to thoughts, feelings and experiences continually reinforce and strengthen our narratives and rationalizations. In modern Western psychology the tool to remedy distortion is termed cognitive reconstruction. One can learn to recognize weaknesses in beliefs, dysfunctional emotions that produce irrational thinking and resulting behaviors like stress, depression and anxiety, etc. Once these emotions are seen, and the motivations behind them are recognized, one can take responsibility for them. Then one's cognitive streaming can be changed, which will allow one to freely explore their internal and external worlds without the distortions of attachment and clinging. This may require changing cognitive streaming that has developed from early childhood.

The above scenarios enforce the view that the life of an organization reflects history many times over, where we fail to learn the lessons of previous dysfunction and failure of organizations to function optimally. This model tends to look negatively upon the ways we organize ourselves, with the assumption that the faults in our personalities permeate into the organizations we create and our behavior is generally dysfunctional. From this stance this model doesn't have the optimism that other models have about the ability to organize ourselves, but provides a frame of looking at organizations through the paradigm of consequence of action, linking past, present and future together. The model also shows that our psychic drives and emotions are powerful drivers of our perception, decision making and behavior. The ability of an organization to handle the paradoxes it faces is also a prime determinant of whether it can adapt to a dynamic environment.

This paper has interpreted Samsara as a descriptive theory of the form and being of organizations. The Wheel of Samsara has been interpreted by the author in one way, where there may be other ways to derive other meanings that may add to the knowledge. The usefulness of the Wheel of Samsara is that it defines the 'collective cognitions' throughout the organizational lifecycle. Further, the model introduces the concept of dependent origination into organization theory which may be a useful way of looking at strategy and ethics of organizations, i.e., looking at organizations through the paradigm of consequence.

Hunter, Murray. "The Wheel of Samsara as descriptive dysfunctional organizational typologies." Analysis and Metaphysics, vol. 11, annual 2012, pp. 133+

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

NOTES

(1.) Low, A. (1976), Zen and the Art of Creative Management. New York: Playboy Paperbacks.

(2.) Field, L. (2007), Business and the Buddha: Doing Well by Doing Good. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

(3.) Larkin, G. (1999), Building a Business the Buddhist Way. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

(4.) Batchelor, S. (1997), Buddhism without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening. New York: Penguin, 4.

(5.) One of the first books on emotions within organizations was Fineman, S. (ed.) (2000), Emotions in Organizations. London: Sage.

(6.) Tashi Tsering, Geshe (2006), Buddhist Psychology: The Foundation of Buddhist Thought, Vol. 3. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications, 46.

(7.) The early concept of phenomenology was developed by G.W.L. Hegel, who was interested in exploring the phenomena of conscious experience. These concepts were further developed by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, later enlarged upon by numerous philosophers including Franz Brentano, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Max Scheler, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand and Emmanuel Levinas. Phenomenology looks at the consciousness as a process of experience rather as a static state. Consciousness is seen as a continual process where something is always in view, whether it be a perception of an object, event or fantasy. Therefore to consciousness it is not important whether the object is real or imaginary--the conscious intention exists of the object. In phenomenology the truth is what is intelligible based on one's subjective opinion rather than physical reality. The perceived reality comes from the individual's emotions, which are within the consciousness. The consciousness exists in the lifeworld, which in addition to the physical world includes all life experiences and memories. Some view the world as being completely transparent before the consciousness.

(8.) Attachment in Buddhism is a much wider concept than attachment in psychotherapy where it is primarily concerned about infant/caregiver relationships in early life. Although there are many similarities, the two concepts should not be confused

(9.) Wisdom in Buddhism can be interpreted as acceptance of Karma and conscious awareness of those actions that will bring us happiness and those that will bring us suffering and the understanding of the concept of non-duality, recognizing that there is no permanence.

(10.) The Four Noble Truths are: 1. Our delusions of self cause our suffering, 2. Suffering is a fact of life resulting from our attachment to what we desire, 3. If we extinguish our attachment, we reduce our suffering, and 4. By following the Eightfold Path and developing wisdom, we can alleviate our suffering.

(11.) The Eightfold path consists of right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, mindfulness and right concentration. Practice of the Eightfold Path may assist in raising consciousness to a completely nondualistic view of subject and object.

(12.) Epstein, M. (2001). Going on Being. New York: Broadway Books.

(13.) Dependent origination is a concept describing interrelatedness. It is represented on the other wheel of Samsara in the twelve states of ignorance, mental formation, consciousness, name and form, the six senses, contact, feeling, craving, clinging, becoming, birth and old age, and death. The state of our being and evolution is based on cause and effect. Through this journey our actions have consequences which bring recurring suffering, i.e., action brings suffering and suffering leads to action, in a reciprocal relationship of interdependence we are locked into. Through dependent origination we become locked into patterns like the metaphor of the channel of a stream being embedded and becoming a fixed feature of the geography of an area. This is becoming, a creation of our previous actions which makes up the elements of our personality.

(14.) Watts, A. (1996), Buddhism the Religion of No-Religion: The Edited Transcripts. Boston, MA: Turtle Publishing.

(15.) Trungpa, C. (1975), Glimpses of Abhidharma: From a Seminar on Buddhist Psychology. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications; de Silva, P. (1991), "Buddhist Psychology: A Review of Theory and Practice," Current Psychology: Research and Reviews 9(3): 236-254; Claxton, G. (1990), "Meditation in Buddhist Psychology," in West, M. A. (ed.), The Psychology of Meditation. Oxford: Clarendon Press; Epstein, M. (1995), Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. New York: Basic Books.

(16.) Goleman, D. (2004), Destructive Emotions and How We Can Overcome Them: A Dialogue with the Dalai Lama. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

(17.) Safran, J. D. (2003), "Psychoanalysis and Buddhism as Cultural Institutions," in Safran, J. D. (ed.), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An Unfolding Dialogue. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 1 -34.

(18.) Grossman, P. (2004), "Mindfulness Practice: A Unique Clinical Intervention for the Behavioral Sciences," in Heidenreich, T., and Michalak, J. (eds.), Mindfulness and Acceptance in Psychotherapy. Berlin: DVTG Press, 16-18; Safran, J. D. (2003), "Psychoanalysis and Buddhism as Cultural Institutions," in Safran, J. D. (ed.), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An Unfolding Dialogue. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 1-34; Sherwood, P. M. (2005), "Buddhist Psychology: Marriage of Eastern and Western Psychologies," www.sophiacollege.com/publications/Buudd% 20pschoz.pdf (accessed 20th October 2009).

(19.) Tejguru Sirshree Tejparkhiji (2006), "Detachment from Attachment--Let Bliss Succeed, Let Sorrow Fail," Bombay, Tej Gyan Foundation.

(20.) This would be something like psychic inheritance.

(21.) This would be something like Carl Jung's concept of collective unconscious.

(22.) Tashi Tsering, Geshe (2006), Buddhist Psychology: The Foundation of Buddhist Thought, Vol. 3. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications, 26.

(23.) This has many similarities to some of the concepts in Freudian psychoanalysis. See Wallin, D. J. (2007), Attachment in Psychotherapy. New York: The Guilford Press, 31.

(24.) Metzner, R. (1997), "The Buddhist Six-worlds of Consciousness and Reality," Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 28(2): 155-166; Engler, J. (1993), "Becoming Somebody and Nobody: Psychoanalysis and Buddhism," in Walsh, R. V. (ed.), Paths beyond Ego: The Transpersonal Vision. New York: G. P. Putman & Sons, 118-121; Engler, J. (2003), "Being Somebody and Being Nobody: A Reexamination of the Understanding of Self in Psychoanalysis and Buddhism," in Safran, J. D. (ed.), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An Unfolding Dialogue. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 35-86; Epstein, M. (1995), Thoughts without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective. New York: Basic Books; Epstein, M. (2007), Psychotherapy without the Self- A Buddhist Perspective. London: Yale University Press.

(25.) Welwood, J. (2001), "The Unfolding of Experience: Psychotherapy and Beyond," in Schneider, K. J., Bugental, J. F. T., and Pierson, J. F. (eds.), The Handbook of Humanistic Psychology: Leading Edges in Theory, Research and Practice. London: Sage; Zimberoff, D., and Hartman, D. (2002), "Attachment, Detachment, Nonattachment: Achieving Synthesis," Journal of Heart Centered Therapies 5(1): 3-94.

(26.) For a discussion on the various types of delusions and attachment see Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (2007), Handbook for Mankind: Realizing Your Full Potential as a Human Being. Bangkok, Amarin Publishing (translated from the Thai edition by Aniyanada Bhikkhu Roderick S. Bucknell).

(27.) Vajiranana, M. (1962), Buddhist Meditation in Theory and Practice. Colombo: M. D. Gunasena & Co.

(28.) Freud, S. (ed.) (1926), Inhibition, Symptoms and Anxiety (1964 edition, Vol. 19.) London: Hogarth Press.

(29.) Tashi Tsering, Geshe (2006), op. cit., 54.

(30.) Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (2007). Handbook for Mankind: Realizing Your Full Potential as a Human Being. Bangkok: Amarin Publishing (Translated from the Thai edition by Aniyanada Bhikkhu Roderick S. Bucknell), P. 65.

(31.) Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (1992), Paticcasamuppada: Practical, Dependent, Origination. Bangkok: Vuddhidhamma Fund, 32-41.

(32.) Individuals can have several views of themselves which can change over time depending on life circumstances and on personal and interpersonal processes. External experiences are absorbed into the consciousness and given form through both sense of self and projection onto others.

(33.) Buddhaghosa (1991), The Path of Purification (Visuddhimagga), 5th edn. (translated by Bhikku Nanamoli). Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society.

(34.) Mitchell, R. W. (1993), "Mental Models of Mirror-Self-Recognition: Two Theories," New Ideas in Psychology 3: 295-325.

(35.) Moacanin, R. (1986), Jung's Psychology and Tibetan Buddhism: Western and Eastern Paths to the Heart. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications.

(36.) Bohm, D. (1965), The Special Theory of Relativity. New York: W. A. Benjamin; Boland, R. J., and Hoffman, R. (1983), "Humor in the Machine Shop: An Interpretation of Symbolic Action," in Pondy, L. R., Frost, P. J., Morgan, G., and Dandridge, T. C. (eds.), Organizational Symbolism. Greenwich, CT: Jai Press 187-198.

(37.) Hunter, M. (2012), Opportunity, Strategy, & Entrepreneurship: A MetaTheory, Vol. 1. New York: Nova Scientific Publishers, 240.

(38.) Kotter, J. (2008), A Sense of Urgency. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

(39.) Bardwick, J. M. (1995), Danger in the Comfort Zone: From the Boardroom to the Mailroom--How to Break the Entitlement Habit That's Killing American Business. New York: American Management Association.

(40.) Schramm, C. J. (2010), "Expeditionary Economics: Spurring Growth after Conflicts and Disasters," Foreign Affairs 89: 92.

(41.) Schumpeter, J. (1934), Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

(42.) Hunter, M. (2012), op. cit., 271.

(43.) For a discussion of psychotic tendencies within organizations see Hunter, M. (2011), "The Continuum of Psychotic Organizational Typologies," International Journal of Business and Technopreneurship 1(3): 435-447. Available online at: http://ijbt.unimap.edu.my/images/stories/Oct_2011/ijbt%201_3_4_435-447.pdf

(44.) Beck, A. T. (1976), Cognitive Therapy and Emotional Disorders. New York: International University Press.

(45.) Ghose, L. (2004), "A Study in Buddhist Psychology: Is Buddhism Truly Pro-detachment and Anti-attachment?," Contemporary Buddhism 5(2): 105-120.

(46.) Kobak, R. (1999), "The Emotional Dynamics of Disruptions in Attachment Relationships," in Cassidy, J., and Shaver, P. (eds.), Handbook of Attachment. New York: Guilford Press.

(47.) Govinda, L. A. (1991), Buddhist Reflections. York Beach: S. Weiser.

(48.) Ghose, L. (2004), op. cit.

(49.) Mindfulness is a state of open acceptance of one's own perceptions and sensibilities that helps our experience of being calm, relaxed and alert state of mind and be aware of our thoughts without identifying with them Ladner, L. (2005), "Bringing Mindfulness to Your Practice," Psychology Networker July/August: 19.

(50.) Hanh, T. N. (1976), The Miracle of Mindfulness. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 38.

(51.) Winnicott, D. W. (1965), The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. New York: International University Press; Winnicott, D. W. (1971), Mirror-role of Mother and Family in Child Development. London: Tavistock Publications.

(52.) Das, L. S. (2003), Letting Go of the Person You Used To Be. London: Bantam Books.

(53.) Engler, J. (2003), 36.

(54.) Bowlby, J. (1980), Attachment and Loss. New York: Basic Books.

(55.) Smith, M. (1987), "The Humean Theory of Motivation," Mind 96(381): 36-61.

(56.) Epstein, M. (2007), Psychotherapy without the Self- A Buddhist Perspective. London: Yale University Press.

(57.) Porter, M. E. (1980), Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press, 267.

(58.) King, R. (1994), "Early Yogacara and its Relationship with the Madhyamaka School," Philosophy East & West 44(4): 659-686.

(59.) Griffiths, P. J. (1986), On Being Mindless: Buddhist Meditation and the Mind-Body Problem. La Salle: Open Court.

(60.) Freud, S. (1912), "The Dynamics of Transference," in Strachey, J. (ed.), Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press, 112.

(61.) Welwood, J. (1996), "Reflection and Presence: The Dialectic of SelfKnowledge," The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 28(2): 122.