Vocational Education: A new driver for economic diversity in ASEAN?

Vocational education is not second class

Education is generally accepted to be one of the major drivers of economic growth. This is one of the major infrastructural investments any government will channel a large percentage of their GNP into, to build an educational system that will support the country's vision of its intended future growth path.

To the majority of the ASEAN economies the intended growth path has been industrialization. Within the education sphere, we have seen a mad scramble by government to create and develop universities as the prime medium to educate their young citizens in discipline-based knowledge that will lend well to enhancing industrial skills and productivity. In Malaysia, this has led to a fevror to achieve high university rankings.

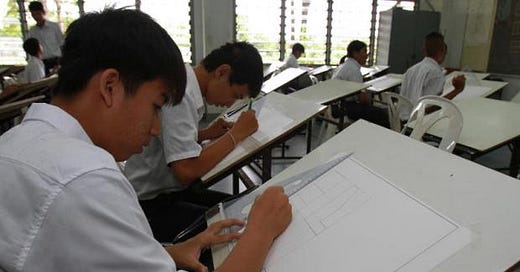

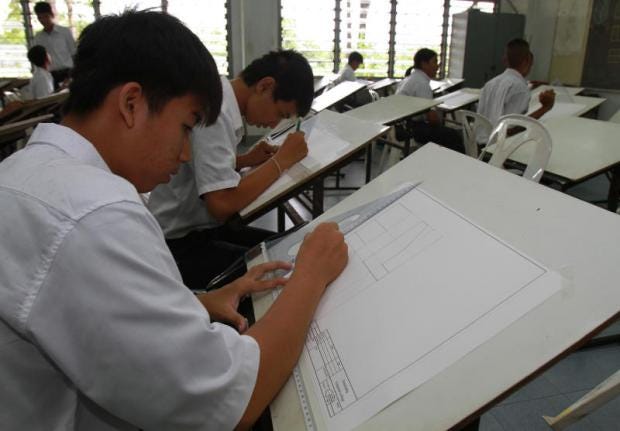

Most ASEAN governments have built a number of vocational training schools and institutes that focus on providing 'hands on' and 'practical skills' in specific trades like engineering, electronics, automotive, ICT, petrochemical, tourism and hospitality, food, textiles, agriculture, and nursing, etc. These institutions are in parallel to the university system, principally aimed to provide higher education opportunities to students who could not be generally be accepted into universities.

Practical skills are the most needed today

For this reason, vocational education has long been depicted as second class, which prompted the Government of Malaysia to upgrade vocational schools into colleges with certificate and diploma structures that resembled university structures. As such, most courses are two and four year long with the objective of placing the student into the industrial workforce after graduation.

Vocational education has long been depicted as second class

However, the evolving social-economic panorama within the ASEAN region is shifting dramatically. The major cities in the region can be considered fully developed metropolises in the economic sense of the word. In contrast, many rural areas are still very much underdeveloped. These areas are losing skilled people, who drift to the cities with expectations of 'big economic opportunities', leading to a labor and expertise drain in rural areas. This rural malaise has been compounded with the collapse in the prices of commodities like rubber of late.

There has been a great emphasis on creating the economic usefulness of graduates. In Thailand for example, most vocational colleges are in the hands of the private sector which produce high numbers of graduates with certificates and diplomas, targeting career jobs in industry, medical, hospitality, and the service sectors. Malaysian polytechnics are producing graduates with diplomas in disciplines like robotic studies, which are only useful in specific industries. Polytechnics are created on the premise of providing infrastructure to produce human capital to service foreign manufacturers in specific industries.

The vocational education infrastructure within the ASEAN region, with its emphasis on developing industrial skills for industry, has been largely at the expense of creating craft and skills-based education that would assist enterprise start-ups of micro-SMEs.

With the changing economic landscape, ASEAN policy makers need to look beyond industry as the prime economic driver. They need to consider new paradigms of education beyond developing industrial skills to increase diversity and create new and enhanced value in their respective economies today.

Business schools have been generally considered the centres where most new entrepreneurs will be created. However, the curriculums and modes of teaching are not installing creativity and innovation very well into their cohorts. This can be best seen with final year students doing useless unpaid jobs at banks, airports, and government departments, giving queue-cards to customers for their internships. By their very nature, business schools with no technology anchors are not coupling general business skills with technical skills. They disseminate business knowledge without the 'hands on' enterprise skills which are needed to set up new businesses. In effect students within ASEAN business schools are getting an incomplete entrepreneurial education.

Many business degrees lead to menial retail work

This is where vocational education can step in. Vocational training should become much wider than occupational training and incorporate entrepreneurship as one of the prime objectives. There needs to be a focus within curriculum about how to develop value through innovation.

There have been some successes in the area of coupling business skills with technology through many of the agricultural colleges and institutes in both Thailand and Malaysia, where many very competent agro-entrepreneurs have been created. In particular, Thailand has showed great success in developing appropriate agricultural technologies with innovative renewable energy production systems, which have had a major impact on farming within the country. Community colleges and informal programs in both countries have created many successful rural based micro-entrepreneurs.

This type of approach needs to be expanded across all activities in the economy to create even more diversified value and diversity at the SME level within the economy.

However, attempts in Malaysia to widen this have generally been lackluster. Both ministry and private contractors have tended to use 'standard modules' on entrepreneurship, which tend to be really about small business, leaving out important entrepreneurial issues about how to be creative in an enterprise sense, apply innovation to a business model, and develop new products rather than copy others. These courses are also most often taught by people who themselves have never been entrepreneurs.

If one agrees with the premise that entrepreneurship is one of the prime activities that can create new sources of value within economies, then practical entrepreneurial education is of utmost importance. So, this is the basic challenge ahead for vocational education within the ASEAN region. ASEAN countries will need to develop enriched economies filled with diversity, which can only be achieved through creating value. However, this is something that current micro-SMEs struggle to do as they are primarily only really duplicating other micro-SME activities, as copy-cat businesses.

A major rethink is needed.

Business school education is creating more executives and clerks to fill offices within the major cities of the region. Business schools have generally failed in coupling business knowledge with technology.

In addition, multinational manufacturers are not the long-term answer to economic growth. They have proved to be very fickle, moving to lower cost production bases as host current host countries lose their competitiveness. Wealth and diversity will come from SMEs in the future. Vocational education may be the best vehicle in helping to create these attributes in the nation's youth.

Vocational education will be better able to serve the growing number of seniorpreneurs start new businesses, with short course formats. As unemployment increases and human life spans continue to lengthen in the region, entrepreneurship education for seniorpreneurs will be critical to prevent new bouts of urban poverty erupt within the region.

The youth today need seniorpreneurs as mentors

If vocational education becomes the vanguard of reframing education focus away from developing industry skills back to developing community enterprise, then the objectives of these institutions need to change. Rather than focusing on industrial employability, the primary objective needs to be personal development within an entrepreneurial culture.

This is going to lead to a few problems. There has been an emphasis on building structured curriculums with diploma structures within the vocational system, in an attempt to make vocational education a stepping stone to further study in other higher education institutions, rather than gain a trade. The concept of disciplinary education needs to be widened to accommodate appropriate (rather than industrial) technology-based enterprise approaches. The vocational system needs build competence and install confidence in students. This type of education doesn't have to be diploma based. It will be better served through short courses and mentorship.

Mentorship points to a second problem, that of getting enough competent teachers for this approach. This is where the governing ministries and quality assurance agencies must accept experience over qualifications and consider allowing retired experienced and practical people to become part-time teachers of entrepreneurship as practidemics. This approach has been successfully adopted by Tecnologico de Monterrey of Mexico, now considered to be one of the leading entrepreneurship universities in the world today.

As there is a need for both enterprises and labor markets to be much more diverse than before, vocational education must come to the forefront. Vocational education should produce better accountants, chefs, agriculturalists, tourist operators, and small-scale engineers, who can create new sources of value, than the university structure. Focus needs to be put on specific educational needs, rather than forcing students to take compulsory studies on Asian Civilization, etc., in a university environment.

Research indicates and experience shows that potential entrepreneurs will be better suited to short courses within a vocational system rather than the longer tertiary education route. Highly motivated people tend to have much shorter attention spans. This list of successful entrepreneurs who dropped out of university due to boredom is large and impressive.

This is the challenge in the next decade that goes out to all ASEAN governments. They need to view the entrepreneurial economy as the next carryover stage of development, from the current industrial stages the larger ASEAN economies are now immersed within. They need to change the educational paradigms within their vocational systems to take the best advantage of this opportunity.

Originally published in the Asian Correspondent 22nd June 2015

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here: