What's with all the hype - a look at aspirational marketing

Aspirational brands can occupy a defined market space at the highest premium

Oh Lord wont you buy me a Mercedes Benz

My friends all drive Porsches, I must make amends

Worked hard all my lifetime, no help from my friends

So oh lord wont you buy me a Mercedes Benz

Janis Joplin

Our realities are about what we dream and would like it to be rather than what it is. Aspirational brand strategy is concerned with creating the dream and generating positive emotional reactions from emotional reactions from consumers (Hill 2010). An aspirational brand strategy tries to fit a product into consumers’ attitudes and emotions so they will identify with the product. Aspirational brand strategy is based on the premise that emotions play an important role in our purchase decision making and that rationality in purchase decision making is fallacy (Mckee 2007). And this cannot be seen more clearly through the Chanels, Yves Saint Laurents, L’Oréals, and Hugo boss’s of this world.

Aspirational brand strategy may appeal to a person’s psychological, social and/or economic aspirations, rather than their psychological, social and/or economic realities. Aspirational brand strategy positions a product or service through image, appealing to what they want to be. Customer loyalty is built up by creating stories about the product rather than relying on product features to see the product. The effect is to differentiate a product or service through emotions. No real claims are made through this strategy, as it aims to win hearts rather than minds and is used powerfully in the fragrance, cosmetic and personal care markets. In this way premium prices can be put on products as emotional value has been created. The strength of aspirational brand strategy in creating a source of competitive advantage is that a product feature can always be matched by a competitor and a claim can be imitated, but the same emotions are hard to create in consumers for similar products. For this reason, aspirational brands can occupy a defined market space by themselves.

Aspirational brand strategy has emerged out of a world where diversity is a marketplace phenomena and there is now an explosion of choice in contrast to the markets of half a century ago where the important consumer goods at the time were automobiles, refrigerators, televisions, etc. that were sold on features. This started changing in the 1970s when segmenting started to grow and every different type of product feature was used to develop market share over competitors. This grew to the stage in highly developed markets where primary product image builders (advertising, promotion, price and packaging) could not be used effectively to differentiate products and intangible attributes became the major means of achieving product differentiation (Hunter 1995). Now themes are the great product differentiators where a total product and company must become integrated to deliver a message to the consumer.

This theme approach to new product development is a useful tool to meet consumer paradigm shifts occurring in various markets. Several contemporary themes can be equated with a number of growing consumer segments.

Some contemporary Western consumers are losing their faith and trust in the established institutions of the Western culture, including the church, government and corporations. This loss of faith and trust is creating a spiritual vacuum where consumers are searching for something that is missing. There is a similar situation in China where growing middle-upper class have been brought up without religion and no longer feel affinity to the “old revolutionary culture” of China. This situation is leading consumers in a number of directions;

As society is becoming more ‘self centred’ in their aspirations, custom made goods and personal customer service is now very important. This can be seen in the rise of private banking, custom made computers and cars, tailor-made suits and fashions, and shopping for unique items in specialized shops rather than chains.

Consumers are looking for unique items that are hand-made, exclusive and come from an ethical background to fill the spiritual void. The rise of Fair-trade and establishment of farmers markets and eco-tourism is providing consumers with more fulfilling consumption experiences.

Consumer alternatism gives rise to alternative marketing and promotional strategies such as viral marketing and on-line buying through the internet. Shopping in this way provides the consumer with a story and feeling of control.

Seeking alternatives is leading to less consumer brand loyalty and more experimentation with new products and new brands, as well as quick changes, meaning shorter product lifecycles. The development of new brands and new images is more widely accepted than before. New brands and images give new experiences like the low-cost airline Air Asia has done in winning new customers in South East Asia. Likewise, adventure and eco-tourism is rapidly growing as consumers look for new experiences in their leisure time.

The new generation feels no guilt about ‘over the top’ luxury as the post war generation did. Top luxury is acceptable to both self-esteem and social exposure as this generation fulfils are role in a live for today in the white-collar professional job market. Luxury is about feeling good and looking good.

People are very concerned about health and the sector is growing rapidly with five-star private hospitals, health tourism and the rise of nutraceuticals and cosmoceuticals. Organic foods sold at premium prices are growing. Sportswear and sports equipment is about being seen and trendy, gyms are full and racing bikes dominate the roads during weekends.

People want to deal with corporate entities that do the right thing. People are then doing the right thing by association – a kind of spiritual materialism. This shows in the rise of ethical products and companies with social programs and supply chains that benefit those that are not as fortunate

Many paradoxes exist in consumers where for example they see no conflict in being concerned for the poor and needy and surrounding themselves in luxury, or see no inconsistencies in taking a budget airline to a holiday resort location and staying at a five-star resort (Hunter 2009, P. 573).

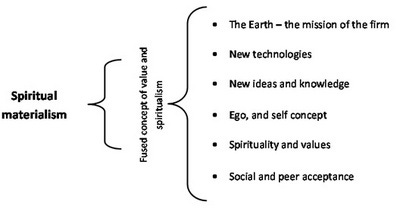

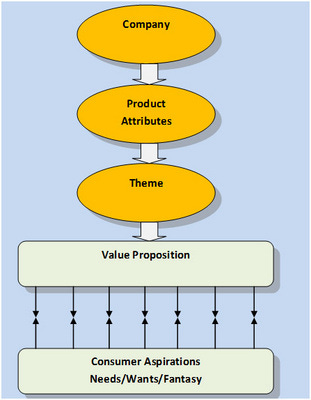

Consumers have values, aspirations and paradoxes and are exposed to new technologies, ideas, and products on a daily basis. Consumers are not so much looking for products that satisfy needs as much as they are seeking experiences and business models that touch their spiritual side. Psychological satisfaction is thus consequently the strongest differentiation a marketer can create (Davis 2002). Social media is connecting consumers in a way that has never been seen before where products become a narrative and marketers don’t have full control of their branding and image and need to collaborate with customers. Products must achieve a balance between spiritualism and also satisfy material wants and desires at the customer, employee, and shareholder level to be successful. Companies must integrate their values into their products. The issues that any firm must satisfy in order to successfully develop an aspirational brand strategy is to balance the concept of spiritual materialism that consumers look for in a product to make a connection as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The concept of spiritual materialism.

Aspirational brand strategy is about being innovative and providing people with the means of fulfilling their aspirations and can be applied in almost any market. Unilever’s strategy in India to service the bottom of the market by creating pack sizes that can be used on a daily basis and selling them through ‘moms and pops’ stores in the slums is allowing people to pursue their aspirations of becoming a micro-entrepreneur and getting out of poverty (Prahalad 2009). CEMEX Mexico’s scheme to sell the building materials to poor rural families to make home extensions for their married children also fulfils family aspirations for the development of their extended family (Chan Kim & Mauborgne 2005). Village technology breakthroughs in India that improve infrastructure in villages helps satisfy peoples’ aspirations for better lives (Hart & Christensen 2002).

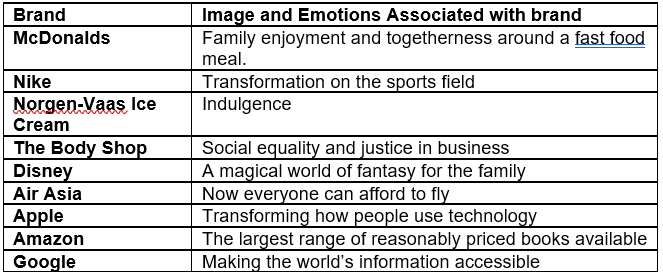

Companies spend hundreds of millions of dollars on projecting an aspirational image to consumers through sounds, images, colours and celebrities to trigger responses from consumers. Fictional and real characters like Colonel Saunders (KFC), Ronald McDonald (McDonalds), Clark Gable (Gordons Gin), Steve McQueen (Ford Motors), and John Travolta (Qantas Airways), etc. are used to add lustre to the products they endorse or act as spokesperson for. Their public recognition, attractiveness, extraordinary lifestyles are characteristics that can be transferred to the product by association (Mc Cracker 1989). Aspirational branding strategy is sometimes related to heroism where founders/CEOs like Sir Richard Branson and Steve Jobs become metaphorical figures for taking on the large corporations like David and Goliath or visionary wizards (Zaltman & Zaltman 2008). Table 1. below lists some well-known brands and the images and emotions associated with them.

The starting point for aspirational brand strategy is imagination (Levitt 1986, P. 127). Product creation requires imagination to construct the customer orientations necessary (Gabay 1998, Postma 1998). But the essence of opportunity also requires consumers to be imaginative, to imagine what it would be like to live at Sanctuary Cove on the Gold Cost of Queensland, Australia, to imagine what it would be like consuming a Ferrero Rocher Chocolate, to imagine climbing the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France, to imagine skiing at Boulder, Colorado during the winter holidays, to imagine owning an Apple iPhone, to imagine wearing Beyonce Perfume, to imagine the benefits to the community a cup of Starbucks Coffee would have, and how that raffle ticket would assist the fight against cancer. Imagination is an aid to practical thinking and opens the door to making purchasing decisions (Brown & Patterson 2000). All our hopes, enlightenment, fears, and desires come from imagination. Brands are able to give consumers a sense of identity and enrich their life experiences.

Table 1. Some major brands and the aspirations they tap

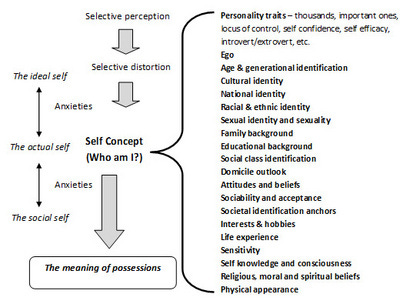

Figure 2. Some of the broad aspects of self concept (Hunter 2012).

Aspirational brand strategy reaches out to a person’s self concept, either their ideal self, their social self, or their actual self. This can be very powerful when appealing to how one would like to be or how one would like others to see the self. This can often relieve anxiety caused by the difference between what a person is and would like to be. One of the keys to aspirational brand strategy is finding out why people really buy products, how people see their own relationship between their own self concept and material possessions. A person may buy a Mercedes to boost their self perception of status, a Porsche for a lost youth or yearn to be noticed, a Volvo for a feeling of safety, or a 4WD for adventure, etc.

A person’s personality and particularly their self concept influences what they buy and consume. There are a number of theories of personality and self concept that places emphasis on different aspects in defining and shaping each theory. Self concept is much wider than personality as it also incorporates their national, cultural, racial, religious and sexual identity which can have a strong bearing on consumption habit. The importance of self concept is to find out a person’s attitudes, beliefs, and motivations so that an aspirational brand strategy can be attuned to them. Figure 2 shows some of the broad aspects of self concept.

Each of the variables above will influence aspirations of individuals. For example, different societal identification anchors or social classes will have different aspirations, but these may differ across different domicile outlooks, racial and ethnic groups, and national identities, etc. But if marketers can find common patterns within selected groups, then these groups can be appealed to. For example, sociable people will tend to go out more with friends and want to have coffee in public places. These groups may have other things they care about such as being able to get on-line to the internet, or being community involved. They may have lots of time to spare or only have time to pick up a coffee on the run. These will influence the brand persona that can be created, something like the persona of what a person would want to be in the Jungian sense. National pride and the threats of globalization was used by the Danish soft-drink manufacturer of Jolly Cola to defend itself against Coca Cola, by creating the images of coca-colonisation turning the symbolism of Coca Cola against itself in the 1980s (Askegaard & Csaba 2000).

However behaviour is also somewhat unpredictable and people do not just react towards incoming stimuli, they also create their own situations and realities upon which they make their choices and act. Some behaviour is related to the stress and anxiety of realizing the gap between the real self and the ideal self and the disappointments that brings. Some people will affiliate with groups that help them cope with stress and buy products that build up their self concept, but not all people act in the same way.

Aspirations filter perceptions so that a person perceives things in their own unique way and makes their own interpretations. Perception is the process through which people filter, select, and organize information to create a meaningful picture of the world. Through the perception process people screen out most stimuli and only select what information that they are attentive to. Through various causes, what is called selective distortion; people interpret information in a way that supports what they already believe. This requires marketers to understand how perceptions will affect consumers’ interpretations of a brand, advertising, and promotion.

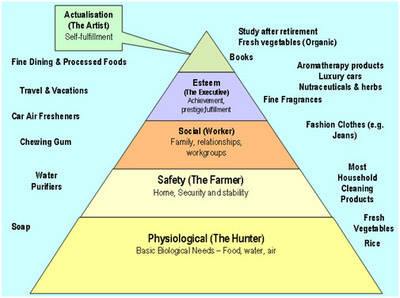

Figure 3. The various levels of needs and products that can be aligned with them.

People acquire attitude and beliefs and evolve their self concepts from life experiences. These attitudes and beliefs influence a person’s buying behaviour. Attitudes consist of peoples’ evaluations, feelings and tendencies towards people, objects, ideas, and situations, and therefore people carry attitudes about almost everything. An attitude determines whether a person likes or dislikes something and usually carries emotions. A belief is a descriptive thought about something which a person thinks is correct. A belief may or may not be based on knowledge, opinion, or faith. Unlike attitudes, beliefs do not necessarily carry with them the same emotions that attitudes carry.

A person’s attitudes fit into their behavioural patterns and are extremely difficult to change. Companies usually try to fit their branding creation into the attitude set, rather than try to change attitudes. There are some exceptions to this and if successful, create very strong unique market positions for firms. In Victoria, Australia milk consumption had been slowly declining for 25 years. The image of milk was that it was just for children to drink at school. Then in 1978 the Victorian Dairy Industry Authority launched the Big M flavoured milk brand with a fun, youthful, and social image, using popular rock bands, models in beach scenes, and themed story lines in a number of massive advertising campaigns. The product established itself as a true alternative to existing soft drinks, changing the attitudes of young consumers.

To turn attitudes into behaviour there must be motivation. A motive is a need that is sufficiently strong for a person to feel an urge to take some form of action to satisfy the need. There are a number of levels of needs that can be aligned with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Maslow 1954). Primary needs consist of biological and safety needs which require satisfaction to survive. After these basic needs are satisfied, social and esteem needs become a concern of individuals, and finally people have some need for their own self actualization, self meaning and understanding[1]. Today consumers tend to search for spiritual resources on top of material fulfilment (Fogel 2000). A consumer typology is related to demographic and psychographic segmentation. Psychographic segmentation is one of the primary marketing tools today, which focuses on lifestyles, attitudes, values and beliefs. This can be illustrated using Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a way to understand market segments (Kotler et. al. 2007). Figure 3. shows product types matched to different needs levels (typologies) of consumers. When a product is matched to consumers’ aspirations and primary, secondary product attributes and strategy is accurately aligned, this theoretically gives a product a maximum chance of success.

As we have seen with the Big M example above, milk could be a basic survival need or with some creativity and imagination repositioned as a social or esteem based product. A single product may generate different levels of need. For example a person may buy a bicycle as a means of transport and exercise. But at another level he or she may want to impress others. At a deeper level he or she may want to feel young and free again. This is where the marketer can select and develop the most powerful needs to build up an aspirational brand.

Once identifying consumer aspirations and summarizing them into a theme, a consumer typology can be created. It is the consumer typology that the new product must appeal to. Product attributes should be designed to match the chosen typology. With this product attribute profile the new product development process can continue onto the other steps, as there is a clear idea of what is really required. The aim is to merge the brand image and the physical product together in synergy so the product presentation (formula, packaging, colour, advertising and corporate image), promotion, and other market strategies become all consistent (Lienado 1984). An example of a potential theme for a hypothetical range of products: Borneo Rainforest products could be as follows; Sabah is on the World list of ‘exotic’ locations; There is Mystic; There is cultural diversity; There is history and heritage; There is nature and serenity; Sabah is a place of peace, health and harmony (Hunter 2006).

Behaviour is complex as it is an interplay between stimuli, the brand, the environment, cues, attitudes and beliefs, and social reinforcements. An aspirational brand strategy hopes to motivate behaviour and if that behaviour leads to a satisfying experience, the consumer will seek to repeat the experience. This is not an easy process to manage even with large resources and a budget. However small SMEs with creative use of viral marketing practices and social media in some cases have been able to utilize these forms of strategies very well.

Branding gives the images to consumers of what companies do and stand for. This makes a person anticipate a certain level of satisfaction or service, where for example a person knows what it is like to fly on Air Asia, eat a Big Mac, or drive a Mercedes. One knows what the company stands for with the branding. The brand projects goodwill, thoughts, myths, realities, which affects consumer’s beliefs and assumptions about the company, its brand, and product. This is why almost more than half the values of companies are made up of goodwill[2]. A summary of the effects of an aspirational brand strategy is shown in Figure 4.

Enterprises must take great care when employing an aspirational brand strategy as the company really needs to be truly integrated with the strategy or consumer skepticism will quickly set in and destroy any concept and image. Employees and shareholders must understand the strategy goals and be part of them with their commitment. BP’s Gulf Crisis in 2010 has shown this and the firm’s aspirations of being environmentally friendly and concerned has taken great damage which will take possibly years to recover.

Figure 4. A summary of the effects of an aspirational brand strategy.

An exert from my book Opportunity, Strategy, and Entrepreneurship: A Meta-Theory, Volume 2, Nova Publishing, New York, 2012

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

Notes

[1] Zohar and Marshall (2004) reveal that Maslow in his later life felt that his pyramid should have been inverted with self actualization being at the bottom. This would place the pursuit of self actualization as the prime need of all human beings. Roll (2006) in another view points out that in Maslow’s hierarchy, self actualization is replaced with the social needs of status, admiration, and affiliation, and autonomy and independence have different connotations in some Asian Societies.

[2] Market price less tangible assets.

References

Askegaard, S. & Csaba, F.F. (2000). The good, the bad and the jolly: taste, image and the symbolic resistance to the coca-colonisation of Denmark, In: Brown, S. & Patterson, A. (Eds.). Imagining Marketing: Art, Aesthetics and the Avant-Garde, London, Routledge, pp. 124-140.

Brown, S. & Patterson, A. (2000). Figments for sales: Marketing, imagination and the artistic imperative, In: Brown, S. & Patterson, A. (Eds.). Imagining Marketing: Art, Aesthetics and the Avant-Garde, London, Routledge, pp. 4-32.

Chan Kim, W., & Mauborgne, R., (2006), Blue Ocean Strategy: How to create uncontested market space and make the competition irrelevant, Boston, Harvard Business Press.

Davis, M. (2002). The new culture of desire: Five radical new strategies that will change your business and your life, New York, Free Press.

Fogel, R. W. (2000). The Fourth Awakening and the Future of Egalitarianism, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Gabay, J. (1998). Imaginative Marketing, London, Teach Yourself Books.

Hart, S.L. & Christensen, C.M. (2002). The great leap: Driving innovation from the base of the pyramid, Sloan management Review, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp. 51-56.

Hill, D. (2010), Emotionomics: Leveraging Emotions for Business Success, London, Kogan Page Ltd.

Hunter, M. (1995). The Evolution of Extrait Perfumes, Cosmetics, Aerosols, and Toiletries in Australia, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 19-24.

Hunter, M. (2006). Efforts to empower the community through essential oil production in Sabah, Proceedings of the Seminar on Community Involvement in Sustainable Bio-Resource and Biotechnology Utilisation, Sabah, Malaysia, 5-6th September.

Hunter, M., (2009), Essential Oils: Art, Science, Agriculture, Industry & Entrepreneurship: A Focus on the Asia-Pacific Region, New York, Nova Scientific Publishers.

Hunter, M., (2012), Opportunity, Strategy, & Entrepreneurship: A Meta-Theory, Vol. 1, New York, Nova Scientific Publishers.

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H. & Hooi, D.H. (2007). Think ASEAN: Rethinking Marketing Toward ASEAN Community 2015, Singapore, McGraw-Hill.

Levitt, T. (1986). The Marketing Imagination, New York, Free Press.

Lienado, R. (1984). The role of fragrance in product development, HAPPI, June, pp. 59-60.

Maslow, A.H. (1954). Motivation and Personality, New York, Harper & Row.

Mc Cracker, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural Foundatiers of the endorsement process, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 310-321.

McKee, S. (2007). Brands: The power of emotion – The sawiest marketers understand that successful product appeal to the heart, not the mind, Bloomberg Businessweek, 8th November, http://www.businessweek.com/smallbiz/content/nov2007/sb2007118_

797874.htm, (accessed 26th November 2010).

Prahalad, C. K, (2009). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, Revised and Updated 5th Anniversary Edition: Eradicating poverty through profits, Upper Saddle River, NJ., Pearson Education, Inc.

Postma, P. (1998). The new marketing era: Marketing to the imagination in a technology driven world, New York, McGraw-Hill.

Zaltman, G. & Zaltman, L. (2008). Marketing Metaphoria: What deep metaphors reveal about the minds of consumers, Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

Zohar, D. & Marshall, I. (2004). Spiritual Capital: Wealth We Can Live By, San Francisco, Berrett-Koehler Publishers.