Who Really Rules Australia? - Donald Horne revisited

A tragic tale of the Australian People

An inconvenient question

The question of "who rules Australia?" is always answered with pet ideas and different theories. We can see symbols of power all around us, but the exercise of real power and influence is rarely a public event. Defining and identifying who really rules Australia is like trying to pinpoint where consciousness exists within our brain. It is complex and illusive. We may have some idea about different entities who potentially exercise power, but can't put any single entity under any precise scrutiny. Besides the formal means of power through authority, ownership and control over regulation, etc., much power is the result of inducement, compromise, promises, flattery, coercion, threats, favors, and even goodwill. Making the situation more complex is that different groups exercise power and influence over different aspects of society. Finally is rule in Australia in the hands of an "oligarchy" that dictates, or is it more likely that the group(s) that rule Australia are more like a football umpire who can influence the flow of the game, with the power to influence formulation of new rules end of season for the next season?

Surprisingly formal academic papers about "who rules Australia" are almost non-existent. A multitude of internet articles, review articles, opinion, and even lectures and documentaries exist online about who rules the world. However in Australia it doesn't seem a question that academics have bothered to write too much about, except for the prominent Australian public intellectual and writer Donald Horne in the mid 1980s, who asked the question in an obscure essay "Who Rules Australia?"

Horne meticulously examined rule from the perspective of our history, significance of the crown, formation of our political system, parliament, political parties, federalism, the role of the media, unions, and banking; proposing that Australians live under a myth about who actually rules them. Although the situation today is very different from the time Horne reflected on these issues, much of his description concerning "who rules Australia" is still valid today. What may be even more starkly relevant is Horne's conclusion, which Australians at the time and even now have taken little notice of.

My intention is to take up from Donald Horne's commentary, update it, and postulate this inconvenient question again in Australia today. Many people know the parts of the puzzle, but by putting them altogether the author hopes it may lead to a more thorough understanding about the intricacies of who really rules Australia.

This paper will do so in the format of looking at each section of potential influence upon Australian society, starting with an encapsulated summary of Australia's sovereign history.

From the Crown to the Commonwealth -Will Australia ever have a independence day?

The formal European claim for sovereignty was made in the name of King George III (1) where upon, a colony New South Wales was established. All legitimate power was exercised under the name of the Crown. Further colonies were proclaimed and established across the continent, ruled by Governors under the authority of the Crown but with advice of the Secretary of State for Colonies. In effect however due to distance and time for messages to reach London and return, Governors were in effectively autocratic control, within the constraints of British law. Eventually Legislative Councils were set up in the colonies to advise governors, who made proclamations. Initially these councils were comprised of appointees of the respective governors, but were later expanded to include elected members until voting franchises were dramatically widened in the 1850s (in New South Wales). Later, completely elected lower houses were established in Australia's colonies which took over most responsibilities of government from the governors.

A British parliamentary act, the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, given Royal Assent by Queen Victoria brought the six colonies together under a Federation in 1901. However, all state and federal governors remained appointees of the British Monarch upon the advice of the British Cabinet (2), where Australia was recognized as a Dominion of the British Empire (3). In addition, the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 was still in force where any Australian or state laws deemed repugnant to Britain would be deemed invalid (4). All bills passed by parliaments must be given Royal Assent by the representative governors to become law.

This division of power between London and Australia at the turn of the century set the tone of history where those in influence have not necessarily acted in the best interests of Australia, a theme that returns a number of times in Australian history as we will see.

One such example in the early 20th Century was upon the British Liberal-Imperialist Ronald Munro-Ferguson's appointment as Governor General in 1914. Munro-Ferguson sort a return to the traditional London-Colony relationship, where Australian politicians were beginning to have their own regional security concerns. Britain prior to the First World War began pulling its ships back to Britain leaving Australia vulnerable. Nevertheless, when war broke out on the European Continent, the Australian Government loyally sent troops who were unnecessarily put in harm's way by British Generals, Gallipoli being a good example.

Munro-Ferguson saw himself first as a British agent to promote the War effort rather than just a representative of the Crown. He personally assisted Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes at the time in his attempt to introduce conscription. When the referendum failed and Hughes was expelled from the Labor party, Munro-Ferguson saw this as a disaster for the British war effort and allowed Hughes to stay on as a minority supported prime minister and form a new party on a "win the war" platform (5).

Some of Britain's Dominions sort a change in their status after the sacrifices made during the first World War (6) ανd a series of Imperial conferences were held in London where the Balfour Declaration of 1926 was agreed to. The declaration agreed that the United kingdom and the Dominions were to be considered autonomous communities within the British Empire with equal status. They would not in any way be subordinate to one another in domestic or external affairs, however they would be united in their continued allegiance to the Crown. It was only after the Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act, 1927 was passed by the British Parliament that the Australian cabinet could directly advise the Sovereign on the choice of Governor General, thus ensuring his independence in office from British interests (7).

However political events in Queensland in 1975 showed that the British Government still exercised influence over state matters in Australia. Sir Colin Hannah, the Governor of Queensland at the time was critical of the Whitlam Federal Government. The British Government had considered dismissing him from office, but due to the dismissal of the Whitlam Government by Sir John Kerr this seemed simply not practical to do (8). The then Queensland Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen sought another term of Governor for Sir Colin. However the British Government advised the Queen that his should not be granted another term. This situation made all state Premiers in Australia realize that they were not advising the Queen through the British Government as they believed, and that it was the British Government that was actually advising the Queen.

The constitutional crisis helped build up determination by the New South Wales Premier Neville Wran to take unilateral action by legislating to stop the ability of parties to appeal to the Privy Council. Wran also wanted the Queen to be required to act on the advice of State Ministers in appointing a State Governor (9), but the British Foreign Secretary at the time at the behest of the Palace indicated that he would advise the Queen to withhold Royal Assent to such Bills.

The Palace resisted the notion that states could advise the Queen directly due to the concern that this could place the Queen in the invidious position of receiving conflicting advice from state and Commonwealth ministers (10). Many different concepts were proposed, but rejected by either the States, Commonwealth, British Government, or the Palace. The matter had also grown into a "states rights" issue, where states did not want to concede more power to the Commonwealth.

It was only when the New South Wales Solicitor General Mary Gaudron was in London for a Privy Council appeal that the issue was resolved with the British Foreign Office. Gaudron convinced the British to open up direct channels of communication to the States (11). These arguments finally received the recognition that Australia was an independent country. Such a precedent was established in Nigeria some years earlier, until Nigeria was proclaimed a republic, and the proposal was put up to the Palace.

Finally, Sir Geoffrey Howe, the British Foreign Secretary at the time agreed to the right of Australian State Premiers to advise the Queen directly as "a consequence of Australia having been established as a federation with a fragmentation of sovereign powers" (12).

Buckingham Palace however continued to object to the proposal where the Queen's private secretary took up negotiation directly with the Commonwealth Government in Australia in the capacity as private secretary of the Queen of Australia. Senator Gareth Evans, Australia's Foreign Minister at the time told the British High Commissioner in Australia that patience was wearing thin and suggested for the first time that the Queen might be formally advised to act despite her own personal objections. Finally the Secretary of Prime Minister and Cabinet of Australia Sir Geoffrey Yeend travelled to London and suggested that in the light of the idea of a republic, the Queen might want to entrench her position in the Australian States (13).

The Queen finally agreed to the Australia Acts with a "convention" to protect the Queen's position where she would be free to read what speech she wanted at any state function (14). The Australia Acts finally ended the responsibility of British Ministers to advise the Queen over Australian State matters (15). This established the concept that the Queen being a separate Crown with respect to each State.

As a consequence, the sovereign is regarded as the legal personality of the Australian state. State land is called Crown land, but actually held by the state. The Crown is thus symbolic, still seen on the emblems of some state law courts, police forces, and Australian Military insignia. The Queen's portrait is still on all Australian coins, the five dollar note, and the symbol of the Crown can still be seen on the One hundred Dollar note.

Although there has been a gradual moving away from the traditional links to the Monarchy, Horne postulated that although the Crown is the symbol of legitimacy of function, symbolically the centre of power is offshore, which has contributed to Australia's sense of "dependence"(16).

However the Crown does signify that there is a power above and beyond elected government. The concept of the Crown creates a spirit of government that has a sense of permanence, where elected Government is only transient. This is where the "mysticism" of a state within a state is created, where anecdotes of this can be seen in government life within Australia today (17).

Where the Monarchy in Australia goes from here, is a matter of conjecture. There have been numerous attempts to kindle debate on an Australian republic, with even a referendum in 1999 (18). However, one of the problems that exist is not so much about Australia becoming a republic, but what form should an Australian republic take. Any progress in Australia heading down the republican road is halted on this point. However opinion polling over the last few years show weak support by Australians for a republic (19). There is conjecture that the republican debate may emerge strongly once again when the death of the current Monarch (20) (21).

The next Issue is what are the real powers of the Australian Governor General?

The Governor General of Australia - Still with undefined powers and more than just the Queen's representative

As we have seen, the Governor general of Australia is the representative of the Monarch of Australia, thus the symbolism of the Crown resides in the office. The functions and roles of the Governor General are specified in the Australian Constitution and include the appointment of the Prime Minister, ministers, ambassadors, judges, giving Royal Assent to bills passed by the Parliament, dissolving Parliament, and issuing writs for elections. The Governor General is also the President of the Federal Executive Council, where the above appointments excepting Prime Ministers and Ministers are made, and Commander in Chief of Australia's defense forces. The Governor General, according to conventions usually acts solely on the advice of the Australian Prime Minister, and usually selects the person who has the confidence of the House of Representatives as the Prime Minister. According to the Constitution the Governor general is appointed by the Queen acting on the advice of the Australian Prime Minister. The Governor General's usual role is a ceremonial one, both domestically and overseas.

However the Governor General has reserve powers that are explicitly stated in the Constitution but subject to convention. These reserve powers include the power to dissolve Parliament, to withhold assent to Bills, and to appoint or dismiss Ministers. Under convention the Governor General would take the advice of the Prime Minister, but the Governor General has the power to act independently (22).

The extent of the Governor General's reserve powers are not absolutely known. Only constitutional situations that arise and corresponding actions taken can define the extent of these powers. In addition, A former Private Secretary to the Governor General Sir John Kerr, Sir David Smith stated in 1988 that "the Governor General is in no sense a delegate of the Queen. The independence of the office is highlighted by changes which have been made in recent years to Royal instruments relating to it.......under section 2 of the Constitution the Governor general is the Queen's representative and exercises certain royal prerogative powers and functions; under section 61 of the Constitution the Governor General is the holder of quite a separate and independent office created, not by the Crown, but by the Constitution, and empowered to exercise, in his own right as governor general and not as a representative or delegate of the Queen, all the powers and functions of Australia's head of state"(23).

This appears to be confirmed by a reply from the Queen's private Secretary Sir Martin Charteris, dated 17th November 1975 in reply to a letter written to the Queen by the then Speaker of the House of Representatives on the matter of the Prime Minister's dismissal by Sir John Kerr, Governor General of Australia on 11th November 1975; "As we understand here, the Australian Constitution firmly places the prerogative powers of the crown in the hands of the Governor general as the representative of the Queen of Australia. The only person competent to commission an Australian Prime Minister is the Governor General, and the Queen has no part in the decisions which the Governor general must take in accordance with the Constitution. Her Majesty, as Queen of Australia, is watching events in Canberra with close interest and attention, but it would not be proper for her to intervene in person in matters which are so clearly placed within the jurisdiction of the Governor General by the Constitution Act"(24).

The Governor General Sir John Kerr used his reserve powers to resolve the Constitutional crisis of 1975. This has caused much controversy because it was also a political crisis, and there has been much conjecture since about Sir john Kerr's influences and motivations. Without re-opening the debate which has been going on since the dismissal, although there is conjecture about foreign intervention (25), evidence based on accounts by those participating in those events tend to suggest that Kerr toke the action he did out of a sense of destiny (26). He was a lawyer by training, a judge by career, and had a deep sense of the law. There is no other convincing evidence to conclude otherwise, although all Labor Governments since that dismissal have worked hard on developing a very strong relationship with the US, and all Labor Prime Ministers have enjoyed their personal relationships with US Presidents. In addition, no Government has ever attempted to borrow funds outside traditional means of raising funds for a government.

Power and Australian Politics - Living in a temporary world

Australia appears to have a vibrant representative democracy. The Australian political system is centered upon parliaments around the country and which party commands the majority of seats in each legislature and forms a government. If the government doesn't perform to the satisfaction of the public, electors in the next election have the opportunity to vote out the government and install another one in its place. Over the last few decades this has been the pattern where both major parties have each spent time in government and opposition. Democracy seems to be well in Australia.

The Australian House of Representative is primarily an electoral college to determine who has the right to govern. Even in the life of the current Parliament where the Gillard labor Government is in a minority, the primary aim of the house is to facilitate the executive (27). Debates within the Australian Parliament tend to be adversary in nature, usually short of new ideas or constructivism, unless it is in support of a Bill. Most policy discussion, agreements, pledges of support, and collaborations are discussed and decided outside of the Parliament. The committee system in Australia doesn't have the clout and power of those within the US Congress. Political power in Australia appears to be vested in the executive, led by the Prime Minister.

However, entering executive government in Australia appears to be restricted to those that make politics their career (28). This has been the case with only a few exceptions. A person joins one of the two major political parties and rises through the ranks within the party by making alliances, joining factions, collaborating with others to gain support and influence, eventually winning pre-selection as an electoral candidate in a constituency and makes it to parliament. Inside the parliamentary party, these career politicians continue to build alliances and a few become leaders which entitles them to become either prime minister or opposition leader. Consequently a person can become the Prime Minister of Australia on the votes of around just 100 parliamentary colleagues. The Prime Minister then selects (or in the case of the ALP ministerial posts are also voted upon where the Prime Minister allocates portfolios) to form a ministry and cabinet. What is important to understand here is that the Prime Minister of Australia and Ministers come from a very select group of mostly career people.

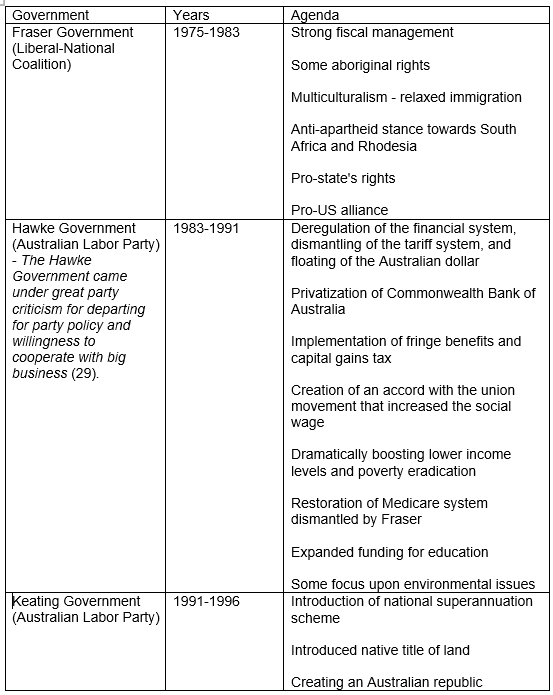

What is most interesting here is that most leaders of parliamentary parties who are either Prime Minister or leader of the Opposition have been elected based upon an agenda they present rather than the strict party platform. If Prime Minister, he or she rules on agenda rather than party policy. Prime Ministers and Governments run on agenda rather than policy of late in Australia (see Table 1).

Table 1: Pursued Agenda of Recent Australian Governments

There is little point for NGOs, lobbyists, and interest groups to talk to political party machinery. Most lobbying is undertaken directly to Government in Australia. The party is effectively only a campaign and selector of who will become a member of the parliamentary party. There is a fear that while Australian politics has the trappings of a democracy, it masks an oligarchy where political power rests with only a few rich and powerful citizens and corporations (30).

The reality is that political power in Australia is something very temporary. Individuals through a network of supporters who are able to negotiate, garner support, reach compromises and collaborations within a party with the majority of members (or supporters) in the lower house of parliament can become the Prime minister and run an agenda that he or she has agreed upon in deals and bargaining both with party stalwarts and parliamentary members of the party. This alliance build upon all these contingencies will only last a couple of parliamentary terms maximum, or until another group within the parliamentary party musters up enough support to dislodge the sitting leader.

Consequently, power is limited to agenda and both outside and inside groups of influence allow a prime minister to hold office for the time the agenda suits them (31). If a prime minister falls out of favor with any of these groups, new alliances, agreements, collaborations, and contingencies arise that will eventually change over the reins of power to someone else (32). Thus, political and executive power is only something temporary, where a change also changes all the powerbrokers with them. Power possession is something of a cyclic nature, and it's very rare that any agenda is passed on from one prime minister to another. With any change, there seems to be also a change in agenda. In this way issues (and agendas) are organized into politics while others are organized out (33). So, understanding who is in control is about understanding what the politics is about and who has a say.

Is the Public Service still the real tai-pan of government?

Almost all contact between the people and government and the dissemination of services are directed, managed, and delivered by the Australian or respective state public services. This includes health care, education, policing, public transport, immigration and customs officers, and the armed forces. Behind these frontlines are public servants who administrate and conceptualize, develop, and implement government policies and programs. Traditionally the public service is the principal agent of agenda setting for government and what it should be concerned with (34).

The Australian Government employees over 300,000 people, of which over half are employed within the Australian Public Service. The rest are employed in the Australian Defense Forces, within agencies like Australia Post and Medibank Private, etc. Since 1990, there has been a gradual shift towards a more ‘top-heavy’ public service, with an increasing proportion of employees in the Executive or Senior Executive Service (SES). Correspondingly, a decreasing proportion of employees are now in lower level positions.

Almost all positions (94%) in the senior public service are still dominated by people of white Anglo-Saxon or other European origin (35). In the words of Donald Horne which are still applicable today, these bureaucrats "share personal characteristics, the power elite are uncommonly bright, intellectually dexterous, verbally adroit, hugely persistent, agile, passionate and tough as nails. Very few of them possess a below-average ego. Many of them possess an above-average libido" (36). Over the decades there has been an over proportionate number of public servants who were freemasons compared to the number of freemasons in the general Australian population (37). It is also believed that Freemasonry was particularly strong in sections of the business and trade union communities, as well as in the police and fire services, defence forces and the legal profession (38).

Even though demographics are rapidly changing in Australia, the characteristics of the public service are not following these changes. The APS workforce is less diverse than the Australian community in general, with fewer people with disabilities, fewer Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander employees, and a continued under-representation of women in the senior levels (39). Evidence also exists that the Australian public service has historically exemplified the practice of "social closure" where staff selection has been biased towards those that display of economist characteristics as an 'ideology of recruitment and promotion' serving the interests of groups within the public service (40). In addition there have been accusations of bullying within the public service to ensure conformity to agenda (41), and the misuse of mental health assessments to neutralize complainants (42).

The public service up to the 1970s was almost the sole advisor to the government on policy, agenda, and implementation (43), and not used to having their work open to scrutiny (44). A minister after his or her duty in the electorate, political responsibilities, parliamentary duties has very little time to scrutinize a complex ministry and was almost at the mercy of department heads when it came to advice and policy. However the newly elected Whitlam Government very quickly found frustration with a public service that was not used to being questioned and directed, so governments began using their own appointed advisors on policy matters.

This trend has continued from the 1970s to today where the Rudd Government spent almost $800 million on 6,534 consultancy contracts during its first 18 months in office (45). Public servants have also been seconded to Ministerial offices and become involved in work that is often compromising to their apolitical stance. For example, during critical moments of public policy development and implementation such as the Tampa and ‘children overboard’ refugee crises, public servants have been seen as politically compromised and far from independent, and even become collateral damage in political events (46).

The Gillard Government is planning further cuts to the Australian Public Service, and cap the senior executive level (47). Now ministers are taking the policy lead in their respective portfolios, armed with advice from their own consultants and staffers. However with the environment of 24 hour media cycles and opinion polls, there is risk that policy formulation within ministerial offices is short term orientated (48).

The Administrative Law Monster

The Australian Public Service, state public services, and local government are responsible for enacting, implementing, and enforcing administrative law. There has been an exponential increase in the volume of legislation in the last 50 or so years. In 1955 the Commonwealth Parliament passed a single volume of legislation of 580 pages; in 2005, it passed seven volumes of legislation in excess of 4000 pages. Tax law, migration law, income support law and the Corporations Law are clear examples (49). However, within each new law there is provision for the Minister to make regulations under the Act. Over the last few years there has been an introduction of more than 20,000 new or amended regulations with only 104 repealed, drowning small business in a sea of red tape and burdensome regulation. These administrative laws are set by unelected officials in obscure offices around the country on a daily basis.

The common theme in the different mechanisms of administrative law around the country is an emphasis on the control of over the area of each Act. Officials framing regulations should remain within the scope of that authority. However, this is not easy to determine and through the Administrative Appeals Tribunal expensive to challenge. Technology, especially interconnected ICT is becoming a major tool of power and compliance for agencies without exhibiting very much transparency or accountability. Thus, administrate law has become a means of entrapment where departments like the Australian Taxation Office have issued formal targets of ensuring taxpayer objections to audit decisions are upheld in less than 20% of cases (50), striking a severe blow to the doctrine of transparency, fairness, and objectivity in public service administration (51).

Certainly, at the local government level in Australia there are numerous corruption cases involving local government officials involved with administrative law (52). The sheer volume of regulations, lack of resources to scrutinize by authorities, and lack of time and resources of citizens to understand them has created opportunity for individuals and business to benefit. In addition, a current review of Freedom of Information Legislation by Dr. Allan Hawke may restrict it on the basis of cost justifications further reducing transparency (53).

Consequently, administrative law and technology has gone a long way of creating a "compliance society" in Australia, exercised across all jurisdictions of government and law enforcement agencies. Thus this framework gives government through the enforcement agencies great powers over citizens in most aspects of daily life. Authority comes from regulation produced by unelected people where great difficulty on the part of any citizen to challenge.

One of the "spin offs" of the "compliance society" is an increased cost of living. In addition the start-up and operational costs of businesses rise making the cost of products and services more expensive. The question here is who is this "compliance regime" benefitting?

The Reserve Bank of Australia is looking after whose interests?

The Reserve Bank of Australia was formed in 1960 to take over the role of banknote issuing authority from the Commonwealth Bank. The Reserve Bank also supervised the banks, and governs monetary policy in Australia. Then from 1 July 1998, the banking supervision function was transferred from the RBA to the newly created Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. The Reserve Bank Act was amended also to create a new Payments System Board, with a mandate to promote the safety and efficiency of the Australian payments system. New legislation, the Payment Systems (Regulation) Act 1998 and the Payment Systems and Netting Act 1998 were introduced, giving the Bank relevant powers in this area.

The Reserve Bank Board's obligations with respect to the formulation and implementation of monetary policy are laid out in the Reserve Bank Act. Section 10(2) of the Act states:

‘It is the duty of the Reserve Bank Board, within the limits of its powers, to ensure that the monetary and banking policy of the Bank is directed to the greatest advantage of the people of Australia and that the powers of the Bank ... are exercised in such a manner as, in the opinion of the Reserve Bank Board, will best contribute to:

(a) the stability of the currency of Australia;

(b) the maintenance of full employment in Australia; and

(c) the economic prosperity and welfare of the people of Australia’ (54).

In 1993, the Reserve Bank focused on the objective of price stability where inflation was to be held to an average of 2-3 per cent over a period of years.

In December 2007, following the change of Government, a new Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy was jointly issued by the new Treasurer Wayne Swan, and the Governor of the Reserve Bank, Glenn Stevens. This Statement incorporated substantive amendments enhancing the independence of the Reserve Bank and covered practices regarding transparency and communication. A revised Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy was issued following the 2010 election, which explicitly covered the Reserve Bank's mandate for financial stability (55). Effectively the Reserve bank of Australia became fully autonomous.

The Reserve Bank Board is made up of nine members which include the three ex officio members of the Board, consisting of the Governor of the Reserve Bank, who is Chairman of the Board, the Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank, who is the Deputy Chairman of the Board, and the Secretary to the Treasury. In addition, there are six external members who are appointed by the Treasurer for a period of five years. The board normally meets eleven times each year, of which one of the responsibilities is to set official interest rates (the overnight bank cash rate).

The RBA is intended to be independent of government to enable impartial economic decisions. It effectively controls the country's monetary policy. Public pronouncements by the bank governor can stir stock and currency markets. Those decisions are made by an independent board who get their advice from both formal and informal sources that are undisclosed. This lack of any transparency in decision making can run potential conflict. Former Prime Minister John Howard blamed the Reserve Bank for his election loss in 2007, accusing the bank of meddling in domestic politics by announcing a rate rise (56).

If one undertakes a very quick internet search on the current RBA board members, one will find that the directors have links to multinationals, media, right wing think tanks, and other foreign interests. The Reserve Bank Governor Glenn Stevens, portrayed by the Australian Financial Review as the most powerful man in Australia is an avid New American Standard Bible reader (57). Who is importantly not represented on the RBA board are small business and Australian wage earners.

The RBA has allowed the Australian Dollar to rise to record highs against the US Dollar and other currencies. Although this reflects some weakness in the US Dollar, the Australian Dollar is high in its own right and is attracting inflows from investors wishing to benefit from relatively high interest rates in Australia. The high Australian Dollar although making imports cheaper, which is keeping a check on domestic inflation, is putting exports from Australia in a precarious position, where industries are being devastated, which is costing many thousands of jobs. Rural industries in Australia are also finding it very tough competing against cheap primary produce imports, which over a long period of time could shut down many rural industries all together. The higher Australian Dollar is also making Australian Universities more expensive for foreign students, where drops in enrollments are occurring (58), and a there is also a decline in foreign tourists visiting Australia (59).

There is very little concern from the parliament of executive government on the loss of industry and employment. Again, the question can be asked, whose interests are the RBA Board acting for?

The Commercial Banks - Too big to fail, too few to be competitive

The ANZ was started in London as The bank of Australasia in 1835. British based shippers, commodity traders, merchants, pastoralists, miners, merchant bankers, and joint-stock bankers, were joined by a group of eminent British businessmen where cross directorships were commonplace, developing a strong relationship with the City dynasty (60). The first bank established in Australia in 1851 was the Bank of New South Wales, where it quickly expanded around the colonies. The early standing of the Anglo-Australian banks in the City of London greatly depended upon who the directors were. The National Bank of Australasia was formed in Melbourne in 1858, and very quickly expanded across the colonies, also opening a branch in London, important for financing wool, gold, and other commodity exports and imports back to Australia. The Commonwealth Bank was formed through the amalgamation of a number of smaller banks under the Commonwealth bank Act 1911 as a savings and general trading bank in a similar fashion to banks that the Australian states had been founded.

Until 1961 the Commonwealth Bank acted as the central bank for the Australian Government. All states owned a savings bank, along with a number of private banks operating under very stringent regulation, where the government used tightly controlled monetary policy to regulate the economy. Bank interest rates and liquidity ratios were tightly controlled thus limiting the profitability of Australian banks (61). Two types of banks were allowed. Savings banks took deposits and paid low interest rates and lent money out for mortgages, while trading banks operated more like merchant banks dealing only with commercial customers. The increase of migration after the Second World War increased savings and opportunities for lending on mortgages, made lending risks very low (62). The booming economy of the 1960s enabled other forms of financial institutions to develop like building societies, credit unions, life assurance, and later finance companies that could charge and pay higher interest rates and also subject to less stringent regulations. The diversity of these institutions greatly restricted growth of the banks in the Australian economy.

The Hawke Government in the 1980s began deregulating the banking sector. There was no longer any distinction between savings and trading banks and banks were allowed to operate in money markets. A partial float of the Australian Dollar and allowing foreign banks to come in and directly compete in retail markets, along with the turbulent economic conditions of that decade led to many mergers and acquisitions by the banks. The Commonwealth bank was privatized during the 1990s in a public offering.

Foreign banks found it very difficult to take up a new license and compete alongside the local banks initially. However, with general liberalization of the Australian economy, foreign banks stated investing in the existing Australian banks from the late 1990s. This was encouraged by the Australian Government adopting the "four pillars" policy that disallowed any mergers between the four Australian banks, ANZ, Westpac, National, and Commonwealth, weakening the influence of the Trade Practices Act, but at the same time allowed foreign banks to takeover any bank (63).

The global crisis of 2008 wiped out Australia's banking diversity and highly competitive banking system. The four major banks aggressively took on the smaller banks like George, BankWest, Bendigo Bank, Aussie, Adelaide Bank, RAMS, Wizard, and Challenge bank, eventually buying most of them up and consolidating the sector into a situation where they control 80-90% of all financial transactions executed across the country. In addition, the introduction of government guarantees for the first time during the 2008 crisis provided the big four banks with a unique competitive advantage.

The above has effectively provided the four major banks with extremely high credit ratings because they are guaranteed "extraordinary government support" in any future financial crisis. This effectively provides the banks with the ability to borrow money at lower rates than other banks, thus putting smaller Australian banks at a great disadvantage.

In addition to the big four banks being able to borrow funds cheaper than their competitors, policy makers have favored their exclusion from the extra capital buffer that the IMF is insisting upon. Extra capital holdings would greatly lessen taxpayer risk with the Government's obligations as a guarantor. An extra capital buffer would also help keep any designs by banks to follow high risk growth strategies in check.

With the four big banks having higher credit ratings, they are able to borrow from the RBA, where smaller banks cannot achieve the ratings required. The big banks are able to issue bonds that are secured with assets where the smaller banks cannot. Over the last few months, the major banks have been able to raise more than $20 Billion of new funding through their AAA-rated covered bonds to government and other investors all around the world in the lucrative environment of a high Australian Dollar and higher interest rates (64).

Government action of guaranteeing private banks according to Mark Bouris has created a "moral hazard" where the banks are insured as too big to fail, which history has shown as a recipe to irresponsible behavior. Government policy has also created a scenario in Australia where the tradeoff between risk and return has been eliminated. In Australia, the lower risk banks with the highest credit ratings are able to provide higher returns than the smaller banks with the lowest credit ratings, a complete reversal of the inverse relationship between risk and return, that the Australian taxpayer has guaranteed (65).

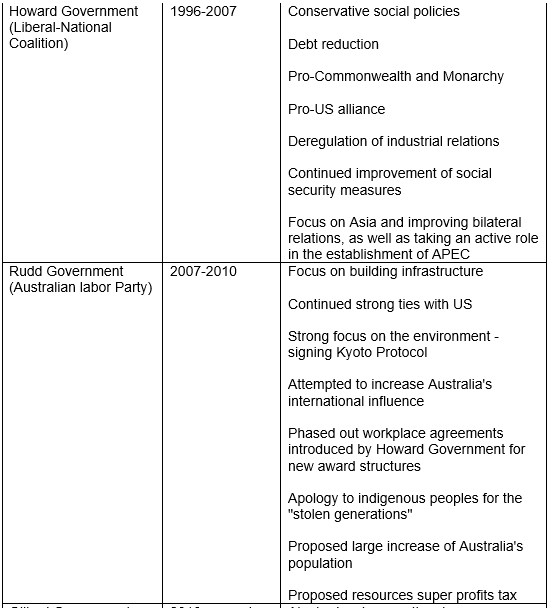

1997 gave the opportunity for foreign equity to flow freely into the banking sector and today the ownership landscape of Australian banks is very different from the traditional idea that Australian banks were owned by the "average Australian" through superannuation and investment funds. Although major shareholders are in fact mutual and investment funds, they are now managed by foreign interests as table 2 shows.

Table 2. Major Shareholders in Australia's "Big Four" banks

Apart from the top four shareholders shown above, an inspection of the data in the respective annual reports shows that most of the other top 20 shareholders are companies with a stake in more than one big bank. Moreover, ownership figures for the second-tier banks, Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited, Suncorp-Metway Limited and Bank of Queensland Limited, show they are also owned by the same organisations that own the big four.

When one looks closely at who owns the big four banks it becomes clear that there is a lot of common ownership, suggesting that those banks may not in fact be independent, competing entities.

Due to the complex nature of the legal structures of shareholders and ways that the various shareholders work together, it is virtually impossible to determine who really controls the banks. Many of the other minor shareholders in the banks also have HSBC, JP Morgan and Citibank, along with many other European and US banks as their major shareholder. This argument is often countered by arguing that HSBS, J.P. Morgan and Citibank are only investing on behalf of small investors. What is of issue here is control and it is the prerogative of the funds to appoint a director to the board of their choice, not the investors. These figures are also consistent with a worldwide study showing that most of the world's company equity is controlled by no more than 25 companies, of which have many of these companies have equity in the Australian banks (71).

One of the most interesting aspects that complement the cross-ownership in the big four Australian banks is the number of cross directorships in other foreign banks and financial institutions that exist in a wide manner. Studies have shown how even small cross-shareholding structures, at a national level, can affect market competition in sectors such as airline, automobile and steel, as well as the financial one (72).

Debt is the financial sector’s key tool to extract wealth from governments, companies and families. The tactic is to load economies (governments, companies and families) with debt, siphon off their income as debt service and then foreclose when debtors lack the means to pay. Indebting government gives creditors a potential lever to pry away land and assets. Currently a massive redistribution of assets is taking place (73). Debt is an extremely powerful method of ruling and controlling what happens in society.

Consumers are losing out in this cross ownership. Interest rates and bank charges are already some of the highest in the world, with the government not seeming to be too concerned. Even financial planning companies are owned by the banks which provide advice on products of which parent companies own, taking away all prudency to customers (74). When banks are found to be wrong, there is very rarely any acknowledgement or apology (75). Many actions such as the four banks all raising interest rates without the RBA raising rates appear to be collusion (76). Banking is now an area where consumers need to be vigilant about their rights to protection, as it appears the Government of today has left the Australian people to the big four's mercy. The four big banks are becoming larger and larger in the Australian economy, to the extent that 2.3 cents in every dollar spent in Australia becomes their pre-tax profit, compared with 0.7 cents in 1986 (77).

Big Business and Mining - Welcome to Australia, the land of oligarchy

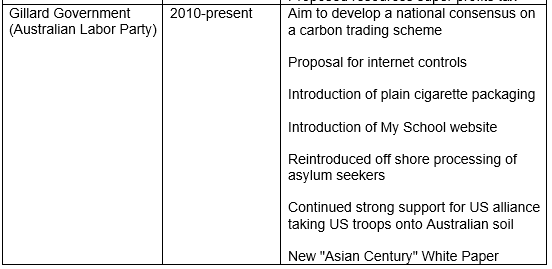

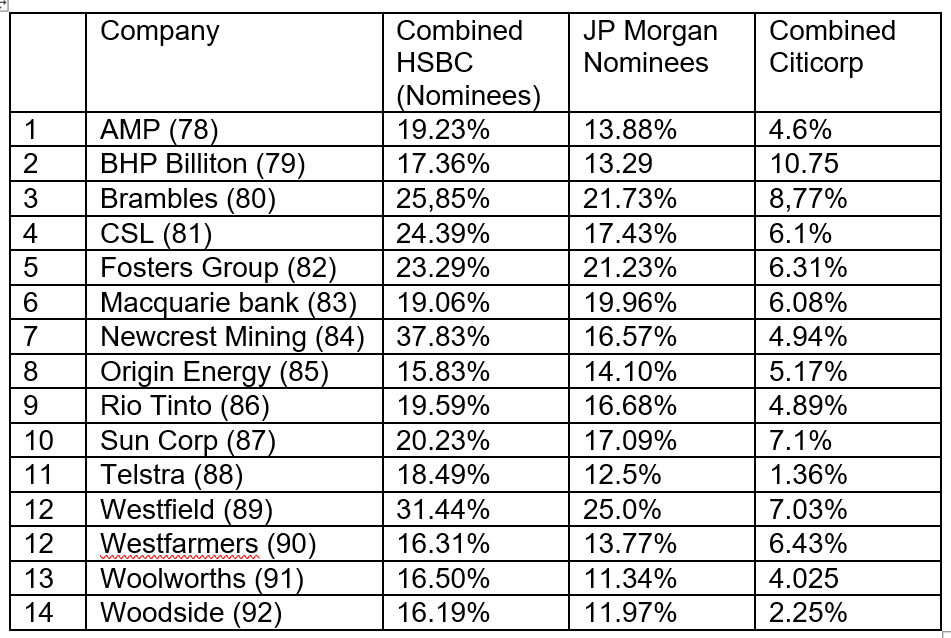

When the ownership of public companies in Australia is examined, one will find that it is very similar to the banks. Both commercial and mining companies ownership are dominated by HSBC Nominees, JP Morgan Nominees, and Citibank Nominees as the top three shareholders of most companies (see table 3). If one examines company directorships there is a tight cross-linking across commerce, banking and mining in Australia today. Commerce, banking and mining are now part of an oligopoly.

Table 3. Major shareholder of Australia's largest public companies

The reality is that much of Australian are owned by faceless people hiding behind big nominee companies that are virtually impossible to research. Not to mention global investment banks, insurance companies and the Commonwealth public servant superannuation scheme. Many companies have directors that are involved in media, banking, and politics, with many ex-politicians coming onto boards when they leave the parliament. We have seen the close relationships between business and politicians over many governments. And Labor has been able to stay long in government with this accommodation with business interests, ever since Bob Hawke achieved an understanding with a significant group within the dominant corporations of Australia (93). Big business probably has greater influence at state level where government can directly facilitate access to prime land and assets that each state contains.

Big business now is able to practice what could be called "bully capitalism" where they dictate terms unfairly to smaller businesses. For example rents charged to tenants in large shopping malls are calculated as a percentage of turnover, with systems that allow landlords to audit tenant sales, where profit is virtually regulated. Supermarkets in Australia now that a duopoly exists with control over 90% of retail sales have been able to increase profit margins from 20% in the 1970s to over 50% today (94).

With so much ownership concentration of Australian business and industry through skillful fund control and use of company law and cross directorships, a very few people can exercise great influence over the Australian economy. Many company boards and directors can operate without much accountability (95). As the recent Jonathon Moylan case has shown, any statement about a company can easily manipulate share prices and make profits or losses of hundreds of Millions of dollars instantly. The potential to easily manipulate share prices is there on a huge scale (96). HSBC Nominees, JP Morgan, and Citicorp Nominees are the 1st, 2nd and 4th largest shareholders in the Australian Stock Exchange as well (97).This has potential consequences for local innovation, consequences for sustainable exploitation of resources, consequences for which industries survive and which industries are lost, and consequences for the cost of living for Australians, not to mention fairness and transparency in the marketplace.

The unions have been big losers

Unions have played a major part in Australian work life for the last century. Up until the early 1990s approximately 50% of the workforce were members of a union. Today union membership is just a fraction of what it was. This decline has been due to the shrinking of the country's manufacturing base, and federal and state legislation prohibiting compulsory unionism and moving towards individual contracts under the Howard Government in 1996. The final factor is structural labour market change. Across the developed world, unions have traditionally had their strongholds in the manufacturing sector, public sector, among full-time workers, and in large firms greatly weakened through industry decimation. The rise of the service sector, downsizing of government, casualisation of the workforce and rise of smaller firms are all changes that have decreased union strength.

Under the Rudd and later Gillard Governments, the Fair Work Act which aimed to bring back collective bargaining, modern awards, minimum wage fixation, dispute resolution, approval of enterprise agreements, and handling claims for unfair dismissal with a body called the Fair Work Commission to Replace the Australian Industrial Relations Commission. However, this change in the industrial relations structure had little effect in raising union membership (98).

What is interesting in the labour sphere is the Gillard Government's plan to bring in foreign workers for the mining industry, under Enterprise Migration Agreements (EMA). This is a very contentious issue with both the unions and some Australians, who see this move as costing Australians jobs, thus politically dangerous (99).

The media - A "closed shop"

The media may have taken over from religion as the prime creator of social reality (100). What becomes important in Australian society very heavily depends upon what the media reports and focuses upon. Reality is what television stations put on the screens each night, newspapers report, and online news sites and social media focus upon. And as a consequence, the media proclaims what is important in politics, the significance of parliamentary debates and how they are projected to the public, and what issues are important in elections (101).

A research project conducted into the Australian media conducted by the Australian Centre for Independent Journalism (ACIJ) scanned through 2,203 different media stories to determine whether there was any bias in stories. The results found that 555 of stories where public relations driven (102). The author has found scanning through news sites that most media organizations prefer their own group of contributors and the Australian online media is basically a "closed shop" for outside opinions, so little diversity of opinion exists. Thus, the consequences of this are that although Australia may have a free media, this does not equate to the right of freedom of expression. There are indeed a narrow range of views put through the Australian media, surprisingly less than other "Western countries". Influential political blogger with US website The Nation, John Nicholls, said in Australia in 2010 that, despite the new “players”, “content” and “platforms”, people have never received less information and less of it from alternative sources (103).

Just like the banks and corporations, the Australian media too appears to be an oligopoly with four major media corporations. Australia is ranked 41st in the world for media diversity (104). Currently two newspaper groups, News Limited and John Fairfax Holdings account for over 90 per cent of the circulation of daily newspapers, and Australia has only three commercial television networks. Even with strict cross ownership laws in Australia with the emergence of the internet media diversification has not increased very much and formats have become very blurred, where a single story from a journalist can now be reported across a number of formats, i.e., radio, television, print, and internet.

In October 2006, the Australian Government introduced new media laws. These amendments reformed the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 which regulates ownership and control rules for commercial television and radio broadcasting, subscription television broadcasting, international broadcasting, data casting transmitters and newspapers. The purpose of the original Act was to encourage diversity and quality of media services, controlling access to the market and the services that are offered. The new ‘two out of three’ rule that allows companies to own up to two media outlets, i.e., television, radio and newspaper in a single area. However, since these amendments foreign and cross ownership has increased, mergers are allowed if the proposed acquisition passes a media diversity test that ensures there are five remaining independent media groups in metropolitan markets and four in regional markets. Under the amended laws, media mergers are subject to the approval of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (105).

There have been many critiques about the political power of media companies like the Murdoch group running their own agenda which favors a particular side of politics, or smears another with very powerful results (106). An example of the extent that the media is intermingled with politics can be seen with the News Corporation scandal of 2011 where allegations of phone hacking and close relations with politicians were aired. Investigations found that News Corporation went as far as obtain private bank information, medical records, and legal files of individuals. The findings of the Leveson Inquiry in the UK indicate just how closely related politicians and the media have been over the last few decades (107). There has been little scrutiny of these issues in Australia.

The national narrative is the source of power

What society discusses and the way society speaks about these issues constitutes what could be called the national narrative. The national narrative encapsulates societies shared assumptions, beliefs, and values about people, issues, events, and situations. Consequently there are a number of national narratives that continually run; such as ideas and realities about the society we live in. The national narrative creates a mental map of our reality. It tells us what is, what should be, what things are like, and what we should value and talk about. The national narrative encapsulates our existence, what is possible and not possible. Narrative tells us how to interpret things and bonds people together in society. Narrative sets our beliefs and values and is a powerful influence upon our actions.

Politics is a set of theatrical narratives. A theatre of people posing a reality that becomes plausible (108). Well crafted drama signifies that the outside world and all within is well (109). For example, the narrative of General Westmoreland about body-counts during the Vietnam War gave the impression of the US winning the war and suppressed the human side of the war. Society has a narrative of freedom, free enterprise, social justice, environmental sustainability, not drinking and driving, smoking is harmful, and the list goes on. Shaping the national narrative is the tool used to install political agenda into society's narratives by those that rule the country.

To see power one must pay attention to the narratives in society. They come through the media, through political statements, advertising campaigns, films and sitcoms, events, stories, artifacts like community and commercial slogans, thought leaders, and education. Power and who rules can be seen through what conflicts exist in society and who are the perpetrators of these conflicts. Who are for and who are against? Are there coalitions?

The strength of the power of who rules can be seen in their reaction to outcry. For example, governments were not influenced by the mass demonstrations against the Vietnam War during the 1960s, and there is little, if no reform of the financial system in response to the occupy movement. This indicates entrenched power whereas the Franklin Dam protests during the 1980s in Tasmania, especially before the 1983 election had positive responses from those campaigning to be rulers (the eventual Hawke Government), as he was facing election. Narratives show what current politics are about and who is involved. Thus the whole political process and who are in position of influence can be seen through the narratives that flow into the public arena and narratives that flow out. Who is setting the national narrative is the same as the one setting the political agenda.

The national narrative rules Australia. So the next question should be "how does the national narrative develop?" Obviously, the Government and media have great influence upon the setting of this narrative. So is it manipulated? Of course. Prime Minister Howard utilized the national narrative to increase gun control after the 1996 Port Arthur massacre, look at the Sandy Hook debate about gun control in the US today. Again Howard used the Tampa affair to rush Border protection legislation through the parliament in 2001 (110), and won an election by claiming that asylum seekers had thrown children overboard in an attempt to secure entry into Australia (111).

One could argue that Australia is a conservative society and not as progressive as many other post industrial societies. There were no pioneering attitudes towards same sex marriages, women in the armed forces, migrants, or drugs. The Australian progressive agenda has always tended to follow rather than lead. Some of the values that can be picked up through observation of Australian society might include;

1. A belief in the status quo has served the nation well and shouldn't be tampered with, i.e., attitudes towards a republic 2. An optimistic belief about the future, i.e., Australians high consumers of debt,

3. A fear of something different imposing change upon society, i.e., support for the "war of terror",

4. A belief in the role of big business as the driver of economic growth and Government as fiscal controller, i.e., peoples tolerance to high bank charges,

5. A belief in economic growth and development, i.e., peoples low scrutiny of mining policies and little public outrage when the "mining super tax" wasn't introduced,

6. A belief in the US alliance, Australian general support for US bases, US troops on Australian soil and Australia's participation in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and

7. A belief in acquiring debt to achieve the Australian dream and live through capitalism, i.e., Australian's high propensity towards debt consumption.

These narratives and the beliefs and values that go along with them often hide the truth from the average Australian. For example, with the belief in capitalism, Australians may believe that to mean the laissez-faire flourishing of small business and entrepreneurial opportunity, hiding the reality that the Australian economy is actually oligoplistic and government protected (112). But the myth created through the narrative covers the realities of what goes on and eliminates scrutiny. A belief in development and economic growth suppresses questioning about resource depletion of mining and the fact that these resources are not renewable. If this was questioned, public support for the "super tax" on mining may have been too strong for the government to ignore. The national narrative can also inhibit Australia excelling in new undertakings like the "pivot towards Asia" outlined in Prime Minister Julia Gillard's "Australia in the Asian Century" white paper. Deep set Australia attitudes may hinder the country's engagement with the region due to what the author called and ideology of "Austro-centrism"(113). The national narrative can be a barrier to a change in attitude.

The national narrative controls what is "politically correct" and the tolerance levels for alternative views in Australian society. It is very difficult to question the US alliance in Australia and any suggestion of Australia adopting a Swedish style of neutrality would be scorned (114). Even the suggestion of scrapping Australia's compulsory voting requirement in elections met with strong attacks and accusations that the freedom to vote or not would "encourage extremists" (115). The rulers of Australia control through creating, maintaining, manipulating, spinning, and changing the national narrative.

Advance Australia Where?

When Labor was in opposition before 1972 it acted as an umbrella for the synthesis of many different points of view through very powerful policy committees. However, many of these policies were not conducive to a conservative Australian electorate and ignored by parliamentary leaders who adopted conservative and "popularist" approach. In 1992 Labor's narratives disconnected with its traditional constituency (loss of Hawke's old seat in Wills, centered around Coburg, Melbourne by the ALP to an independent after he left Parliament), while the ALP moved into the middle ground of conservative Australian politics with an economic rationalist agenda and strong realignment with the US alliance. This was in stark contrast to former Prime Minister David Lange in New Zealand banning US warships to NZ ports in 1985. Labor had learned from the Whitlam experiment of the 1970s that it will only be able to govern from the centre in line with the national narrative.

Even the Eureka movement in Ballarat during the 1850s was not the radical movement that today's mythology depicts (116). The radicalism was a complete myth. When the leaders of the rebellion became members of the Victorian Legislative Assembly, where their voting records show a very conservative stance (117). One of the leaders Peter Lalor claimed he was never a democrat in the sense of Communism or Republicanism, but just fighting the cause of a tyrannical government (118).

Australians are not liberal innovators in political philosophy. Action, including the Gallipoli landing shows Australians to be accepting of the establishment and conservative, rather than the innovators we have been portrayed to be. This conservatism has been very costly to the real interests of Australia.

Inherited cultural values have disadvantaged Australian's and prevented adaptation to the hostile environment of Australia when they first settled (119). Australians allowed themselves to be subjected to the rivalries of Europe in 1914, the common market in the 70s (120), and global geopolitics with the ANZUS alliance.

Australian introduced sheep rather than develop kangaroo as a staple food, introduced European species into the natural environment with catastrophic consequences, and adopted the "level playing field" as an economic philosophy, without really thinking what benefit it had for Australia. Imported ideas over history have only caused problems like the rabbit proof fence (121). Tax deductions for clearing land and phosphate bounty only assisting in degrading Australia's natural environment (122). All these have been great tragedies for Australia.

The rhetoric of the rulers doesn't meet the reality. The great myth is that Australia is a competitive economy. Most of Australia's largest companies have either monopolies or exercise some form of oligopoly. For example;

BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto, Woodside Petroleum, Newcrest Minerals, Fortescue Mining and Origin Energy all have monopoly control over the resources they exploit,

The four major banks exercise almost 90% control over all transactions in the economy and the smaller banks have the same shareholding as the 'big four" as well,

News Corporation controls over 80% of all metropolitan newspapers in Australia,

Westfarmers operate Coles, Bunnings, Target, Kmart, Officeworks in duopoly markets,

Telstra has a near monopoly,

Woolworths operates in a duopoly with Coles.

Westfield group operates a unique group of shopping centres without competition, and

CSL has an almost complete monopoly on all blood products.

The top businesses in Australia do not exist within competitive environments and are able to earn above average profits. The reality of Australia itself has become a lie and cover-up. No such environment could have been created without collusion, corruption, and cover-up, unless it was stupidity.

British ownership in Australia has always been high and considered friendly. Australians have tended to assume that the banks and big business were primarily owned by superannuation funds investing on behalf of average Australians. This belief gave credibility to the banks where there huge profits are palatable to the Australian public. But this is a myth. Shareholding records show equity funds in positions of great influence in banking, business, mining, and media. Equity funds are designed where they are managed by HSBC or JP Morgan Nominees, where through cross equities, mergers, and acquisitions these firms are part of the "25" who own a great proportion of the world's banking and finance business. The procedures and rules for selecting directors with an array of cooperation and collaboration could give strong influence, if not control to these firms in almost every aspect of Australian's life. We have seen the large extent of cross directorships that are people selected from a very narrow group of professional people with career connections to the big names in the financial world. A large matrix of cross ownership also occurs and we have seen only a little of the extent they are used to circumvent national rules and taxes in the media. However we cannot know for sure the true situation as determining who truly owns these corporations is virtually impossible.

likewise in foreign policy, Australia has become almost totally subservient to US interests, even at the cost of our own interests in the Asian region. China is our major trading partner and not a military threat as US policy action is making out. Australia viewing its largest trading partner as a potential threat, is beyond commonsense. The Australian Government has shown great immaturity in this area that has in many ways compromised our neighbors views of Australia as an independent country with its own will (123).

Conservative Australians don't subscribe very well to conspiracy theories. Whitlam found that out in 1975 when Australians didn't maintain their rage about his government's dismissal being more concerned about economic management. Australians like to see and believe, which assisted Howard win the 2001 election over the story of boat people throwing their children overboard. Australians were equally accepting of the need to invade Vietnam, to stop the red peril, Afghanistan to flush out Osama Bin Laden, and Iraq to stop Saddam Hussein using WMD on the free world. Even today there is little public questioning of these matters unlike the UK where there is an inquiry into Britain's role in Iraq. Just like Governor General Ronald Munro-Ferguson using his position to send Australians to the other side of the world for Britain in WWII, Australians needlessly died in Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq over another country's agenda.

As Donald Horne stated in his essay "Who Rules Australia", "it seems there is little dispute that business interests prevail in Australia" (124). Business is setting the agenda, not government. Worse still government has become dependent upon business to keep the economy running. The state only helps to manage the economy so that businesses can make profits and continue to administer society so that even more profits can be made. It is also apparent that businesses now are the group that make decisions about taxes and labor conditions. Business controls the national narrative and the fate of the environment is primarily left up to business, the government can only react, or bring up concepts like "carbon trading schemes" that make government look concerned. Labor unions have been controlled and industrial democracy in Australia isn't even a dream, although these concepts are advanced in many other post industrial societies. Politicians are transitory characters upon a stage that pursue an agenda they are allowed. Both the tai-pans of the public service and the leaders of the business sectors see prime ministers come and go.

Probably the biggest "conspiracy" over the people is administrative law at all levels of government with little scrutiny over whether all regulation is constitutionally compliant. Agencies under temporary ministers are taking on an authoritarian demeanor of their own acting outside the real scrutiny of an under resourced parliament .

Australia will very soon see UAVs or drones flying over Melbourne and Sydney suburbs looking for pensioners who have taken a Coles or Woolworths shopping cart home with the groceries to prosecute (125). All Australian Governments have legalized casinos and allowed massive expansions even at the great social costs to the community in terms of problem gambling, bankruptcies, dumping children, and suicides (126). Local Governments spend lots of time and money financing entrapment operations against illegal brothels (a victimless crime) on the behest of the large legal operations (127).

Both Government and opposition are often bilateral in many more areas than one thinks. Most of the differences are rhetorical. This has led to cover ups at the highest level of the government machinery, namely the Reserve Bank of Australia by both sides of Australian politics (128). The media is also complacent in scrutinizing these issues.

Australia is not being ruled for the benefit of Australia, but rather the sectional groups that yield influence over the country running their own agendas. Secretive nominee companies and an anonymous front for overseas investors who are prepared to destroy the environmental and cultural heritage of Broome and the Dampier Peninsula for profit. Multinationals don't have to own, they control, and utilize the funds from small investors for gaining control. In this way the small investor is captive to the agendas of the fund managers.

The two party adversarial political system is an advantage for other parties of influence in Australia. When the ruling Government or prime minister doesn't support a particular agenda, then parties can support and encourage the other party or internal factions within the prime minister's own party to move and change the policy. The potential of this was seen in the removal of both Prime Minister Rudd and the Liberal Opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull over the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (129).

Urbanization, overgrazing, depletion of resources, salinity (130), water shortages, bush fires, and droughts lack the attention they need. The issues of poor productive soil and depleting minerals are about future of Australia. Australia lost the eucalypts as an indigenous product and the fisheries are now unproductive. Australia is much more like Haiti than a first world political and economic institution with well educated people. Just as early settlers stripped the trees in Australia thinking land was fertile once again the land is being stripped without a replacement. The consequences were invisible then and again seem to be now.

The media has failed to provide a platform to promote any visionary thought. The media's takes a narrow interpretation of what should constitute the national discussion.

What we have seen with the recent HSBC case in the US is that ethics are no longer a consideration for any business it undertakes. So trusting these firms to act in the national interest would be like trusting the goat to look after the cabbage patch.

It is almost impossible to regulate multinationals and there is indeed no show of political will to do so in Australia. The idiom "to big to fail" is now the catch cry when any scandal occurs. Australia is not exempt and public debate to date has not tackled the real issues that survival of the country depends upon. Boat people and asylum seekers seem to be a convenient issue to waste national emotional energy upon while Australian assets are being stripped before the country's eyes. So why the parliament and government in all this ill-informed and complacent, a willing collaborator? These are the questions that nobody is asking.

A lack of vision for Australia by the people and encapsulated by governments is the complacency that allows other interests to come and impose their visions on the country. This is what Donald Horne eluded to with his words "Australia is a lucky country, run by second rate people who share its luck" (131). Australians are too complacent about the country and have allowed entities with agendas contrary to Australian interests to prevail.

To a great extent our own national mythology has blinded us to the realities of how the country really operates. We like to believe in the myth which prevents us from seeing the reality and worse still inhibits a vision for Australian society. All our narratives are within a narrow arc of what is prescribed for us to believe. Anybody prescribing anything else differently will attract anyone of the colorful Australian labels to describe a person who doesn't subscribe to the mediocrity of the Australian dream.

This story above that has unfolded over the years, is not the one of democracy and an egalitarian society that many believe Australia is, but rather as the country that never gained its real independence. Perhaps ANZAC Day on 25th April commemorating the slaughter of Australians at Gallipoli Peninsula under British command in Turkey, symbolic of 'Australia's coming of age' in the national narrative, is also symbolic of Australia not being able to achieve independence and being at the mercy of foreign interests, contrary to those of Australia. As a concluding remark, what Donald Horne wrote almost 30 years ago seem very apt: "there areruling interests that seem to prevail at some time of conflict. But these prevailing interests are not in Australia"(132). Who are the real umpires in Australia?

Journal of Self Governance and Management Economics, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2013, pp 54+

You can subscribe for free emails of future articles here:

References/Notes

[1] See History and present government, The Official Website of the British Monarchy, http://www.royal.gov.uk/MonarchAndCommonwealth/Australia/Historyandpresentgovernment.aspx

[2]. Hudson, W., J., & Sharp, M., P., (1998), Australian Independence: Colony to Reluctant Kingdom, Carleton, Melbourne University Press.

[3] Andrews, E., M., (1993), The ANZAC Illusion: Anglo-Australian relations during World War I, Cambridge, The Cambridge University Press, P. 21.

[4] Craig, J., (1993), Australian Politics: A source book, 2nd Edition, Marrickville, NSW, Harcourt Brace, P. 43

[5]The Times, 31 March 1934; The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 April 1934; The Argus, Melbourne, 31 March 1934

[6] Blackshield, T., & Williams, G., (1998), Australian Constitutional Law and Theory, 2nd Edition, Annandale, NSW, Federation Press, P. 143.

[7] However the Curtin Labor Government appointed Prince Henry, the Duke of Gloucester as Governor General during the Second World War in the hope that the appointment may influence the British Government to send men and equipment to assist in the pacific War.

[8] Twomey, A., (2006), The Chameleon Crown: The Queen and Her Australian Governors, Sydney, Federation Press, Chapters 5 & 13.

[9] Twomey, A., (2006), "The Chameleon Crown", Chapter 14.

[10] Twomey, A., (2007). The Queen of Australia, 19th Conference of the Samuel Griffith Society, Melbourne, http://www.samuelgriffith.org.au/papers/html/volume19/v19chap9.html

[11] Twomey, A., (2007). "The Queen of Australia", P. 83.

[12] Twomey, A., (2007). "The Queen of Australia", P. 85.

[13] Twomey, A., (2007). "The Queen of Australia", P. 85.

[14] Twomey, A., (2006), "The Chameleon Crown", Chapter 20.

[15]Australia Acts 1986, s.10.

[16] Horne, D., (1985), Who Rules Australia?, Daedalus, Vol. 114, No. 1, P. 175.

[17] One can see that the public service in Australia sees itself as autonomous where many ministers have difficulties in dealing with their own departments. Perhaps one example is illustrative where in Adelaide in 1978 during a royal Commission into the dismissal of the Police Commissioner who had been accused of misleading the Premier, justified his actions by claiming he had a deeper loyalty to the Crown which is beyond the elected Government. Through this Monarchic language, a belief that the police and other security agencies may exist that they are the ones who are the true interpreters of what are the best interests of the state. See: Hall, B., (1978), The Secret State, Sydney, Cassell, P. 123.

[18] According to the press, the Queen was amazed that we voted “No” in 1999, Prince Philip said we were “bloody mad” when told the result and Prince Charles has said that Australia should become a republic. See: Keating, M., (2012), Why Australia is waiting for the Queen to die?, The Punch, 4th October, http://www.thepunch.com.au/articles/why-is-australia-waiting-for-the-queen-to-die/#comments

[19] Steketee, M., (2012), Republic? Young want to keep it in the (royal) family, The age..om.au, 20th October, http://www.theage.com.au/national/republic-young-want-to-keep-it-in-the-royal-family-20121019-27wxe.html

[20] Warhurst, J., (2012), Waiting for Queen's death soft option for republic, The Punch, 8th June, http://www.thepunch.com.au/articles/waiting-for-queens-death-soft-option-for-republic/

[21] This view is supported by ex Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam who believes that the affection and respect the Australian people feel for Queen Elizabeth, “Prince Charles does not have”. See: ‘Once the Queen is dead, long live the Republic’, Tony Stephens, SMH, Oct. 31, 2008.

[22] This power is usually used in situations where an election results where no party has a majority and the Governor general may select a Prime Minister, if the Prime Minister losses support of the majority of members in Parliament, then the Governor general may appoint a new Prime Minister, or refuse to dissolve the parliament should he or she be advised to do so by the Prime Minister (however not the power to dissolve the Parliament without advice). This is not an exhausted list and new situations that arise will define the extent of the Governor general's reserve powers.

[23] Smith, D., (2007), A Mate for a head of State, Address to The Sydney Institute, Dixon room, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 24th January, http://www.norepublic.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=1217&Itemid=25

[24] Kerr, J., (1978), Matters for Judgment, Sydney, Macmillan, pp. 374-375.