Do Asian Management Paradigms Exist? A look at four theoretical frames. Part 1

Review of Contemporary Philosophy, Vol. 11, 2012, pp 92-124

Abstract

Interest in Asian business and management practices developed during the Japanese business emergence in the 1980s. The rise of the Asian tigers in the early 1990s and the emergence of China and India in global business affairs during the last decade have kept up the momentum of interest. This paper contemplates the question as to whether specific Asian paradigms of business and management actually exist. The author takes a look at Confucianism, Sun Tzu’s military strategies, Buddhism, and Islam as possible paradigms. However, upon a superficial look at these paradigms, there appears more influence on Western management thought than Asian management thinking, excepting Confucianism.

Introduction

Asian business and management has been of great interest to many ever since the rise of Japan Inc. during the 1980s. The ‘sudden’ [1] Japanese success in the US and European markets was explained by numerous authors as well thought out marketing strategies [2], a strategic mindset [3], Superior productivity [4], organizational culture [5], specific cultural practices and a shared commitment [ 6], a special nexus between government, business, and the banking system [7], and innovation [8]. The rise of the Asian tigers in East and Southeast Asia added to the mystic of Asian management. This lead to a further round of authors espousing reasons for success including work ethics, culture, low cost base, rising levels of innovation, government sponsored capitalism, the role of the overseas Chinese [9], quanxi [10], growing domestic markets, and well thought out strategies [11]. Interest in Asian business and management declined with the Japanese bubble bursting and the Asian financial crisis of 1997. This occurred at a time when there was a small re-emergence of US industry where the Asian myth was broken and it was back to business as usual [12].

US industry became equipped with new paradigms that would solve all their competitive problems packed up in new management philosophies that would bring a new arrogance in executive management, who thought they were envisioned for the future. Tools and slogans like the ‘Value Chain’, ‘Strategic alliances’, ‘Strategic innovation’, ‘Lean Manufacturing’, ‘Business Process Re-engineering’, ‘Balanced Score Card’, ‘Benchmarking’, ‘TQM’, ‘branded derivatives’, ‘Quality Management Systems’, ‘Zero defects’, ‘Performance Measurement’, ’Excellence Model’, and ‘Six Sigma’ instilled new found confidence. Many of these ideas became a ‘quick fix’, with a rapidly growing consulting industry. However, most of these ideas were misinterpreted, as for example, managers saw lean production as a means to cut back on staff and declare themselves a lean organisation.

However the first decade of this Millennium saw China and India begin to emerge as serious global contenders. Interest again returned to Asia with a flood of books published about the success of the new rising giants. Literary focus today is upon the nouveau entrepreneurs of the region, who they are, how they organize themselves and became successful [13]. Most literature about Asian management has been positivist and instrumentalist rather than reflective. This can be seen with title phrases like ‘how’, ‘new competition’, ‘success’, and ‘challenge’, etc. Culture and philosophy has been superficially mentioned and there are indeed a multitude of books about ‘Confucius’ [14], ‘Sun Tzu’ [15], ‘Buddhist management [16]’, and ‘Islamic business [17]’.

After reading so much about Asian management there are still questions to be answered. Is there a distinctively Asian type of management based upon traditional philosophy? Is the focus on these ancient philosophies and religion really relevant to Asian today? This paper has selected four philosophies, first briefly explaining them, and then giving consideration to the relevance within contemporary Asian society. The paper will conclude postulating what types of paradigms and frames may enhance our understanding of Asian business in the future and what similarities they may have to current occidental paradigms.

The Confucian Paradigm

Confucius was born with the name K’ung Ch’iu in the Lũ Kingdom of China in 551 BC, and was in later life called K’ung Fu-Tzu (Master Kung) by his followers. He is probably the most famous Chinese moralist, intellectual, philosopher and educationalist known outside China and his teachings have had great influence on China’s social and political thought over the last 2500 years, as well as spreading to East and South-East Asia [18]. Confucius developed a system that saw man as a social being, interconnected to society through a system of moral and social ethics, concerned with perfecting human character to create a virtuous social order.

While the traditions of Confucianism have historical and regional variations, there are certain central ideas and values which are common. These values have constituted the key elements of the traditions of societies which have endured history and political upheavals. The basic Confucian concepts embrace a dynamic cosmological worldview for promoting harmony amidst change, where individuals exist in concentric circles of relationships with ethical responsibilities that place importance on the family, within a hierarchical social system, where loyalty to elders is paramount and a generational concept of gratitude and respect for earlier ancestors exists. Education is the mechanism where individuals are cultured and developed as a means to enrich society and create a social and political order. History is valued as continuality and a basis for moral reflection and learning.

The worldview purported by Confucius is characterized by four key elements;

1. An anthrop cosmic perspective of the great triad of heaven (a guiding force), earth and humans,

2. An organic holism where the universe is seen as unified, interconnected and interpenetrating, where everything interacts and affects everything else,

3. A dynamic vitalism of underlying units of reality which is constituted of the material energy force of the universe (chi), the natural force of the universe, which creates reciprocity between man and nature and is the substance of life responsible for continuing process of change in the universe, and

4. Ethics embracing man and nature.

Within this context, Confucian thought sees the person in relation to others and not as an isolated individual. Thus, in Confucian society, the common good is more important than individual good. In this view, self interest and altruism for a common cause is not always mutually exclusive.

Confucius was more concerned about the process of human development, rather than theological concepts and ends [19]. He believed the principles of relationships could be extended from that of running a family to the governing of a kingdom or nation; “Those who want to be a leader or ruler have to have their own house in order” [20]. Through education and rituals which signified respect, man would develop five inner virtues; integrity, righteousness, loyalty, reciprocity and human-heartedness, which once developed would radiate externally from the individual, so that society could be governed by man, rather than rules of law. To this end, Confucius defines five primary relationships that will achieve this; ruler and subject, parent and child, elder and younger brother, husband and wife, and friend and friend. As a child develops and learns, he or she will first learn to love and respect the parents, then brothers and sisters, then relatives, and later all of humanity. This piety is called Hsiao, which is considered the root of all humanity.

This philosophy was able to change the family in agrarian China from a unit of production to a collective moral dimension, with a social code for each rank of the family hierarchy, very different from the Western concept of individualism [21]. This led to the concept of guanxi, much written about in Western literature, “a focus on relationships with a shared history, respect for the past, a value that many – not all – Chinese cherish” [22].

Two other concepts in Confucianism are Tao, the way of life and Te, potency and self-sacrificial generosity with humility, with the moral power of attraction and transformation, associated with these qualities. The humanistic attribute required to achieve the above is through Ren, which means love, kindness and goodness, qualities of the perfect individual. This is the essence of what makes humans different from other members of the animal kingdom. Failure to develop Ren would lead an individual to quickly develop foregone conclusions, dogmatism, obstinacy and egotism, which would block wisdom and prevent people from making new insights and discoveries, as one’s mind must remain open to become wiser. Li is the expression of Ren in a social context through norms, rites and rituals governing ceremonies according to one’s social position. Through Li, the individual expresses his respect and reverence for others [23].

Another important aspect of Confucian thought mentioned above is Yi or righteousness. This is where self interest is subservient to organizational interest. Yi is practiced through cultivating ritual and etiquette and eventually becomes second nature. Zhi or wisdom is the ability to apply the above virtues into life situations which implies an understanding of the Confucian worldview above. Zhi is therefore much more than knowledge. Finally, one must possess Xin or trustworthiness to safeguard the mission of the organization. Romar suggested that Confucian ethics are very similar to the ideas developed by Peter Drucker [24].

Confucius was not influential in government during his time, serving only in minor positions, and wondering around China giving advice to those few that listened. However, he attracted a number of followers, who later held office in government, advised by Confucius on matters of ethics and piety. However he became quickly disillusioned as they didn’t take his counsel. Confucius spent most of his last years working on his classics.

After his death, Confucianism had to contend with other philosophies of Taoism and Buddhism during the 3rd to 7th Centuries, creating a blend of philosophies creating Neo-Confucianism, dominating philosophical thought in China during the Tsang Dynasty (618-906 AD), the Sung Dynasty (960-1279 AD) and later during the Ming Dynasty (1472-1529 AD). Confucian institutions in China slowly disintegrated after the overthrow of the Last Emperor in 1911, although it survived in practice in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao and parts of South-East Asia after that time.

Confucianism has been examined and debated about its significance to Asian Economic development by Western scholars, over the last few decades. Confucianism is often misunderstood, as to its real interpretations. Most have believed that Confucianism is completely worldly and humanistic, lacking any divinity. However, Confucius last book The Annals of Spring and Autumn(chũnqĭu) is full of references to the divinity of heaven and its influence upon man and reason for existence. Some scholars have criticized Confucian works as being nothing more than a reaffirmation of earlier thoughts, with no originality [25], although Confucius himself stated the need to look back to learn history as examples of models and acts of piety. Many misunderstand the concept of holism, not necessarily meaning holism of society, but holism of the worldview from a family perspective [26].

During the 1980’s and 1990’s many academics became interested in the connections between Confucianism and the spectacular rise of the Asian Tigers. Some argued that Confucius was opposed to modernization as it didn’t advocate individualism, common to the Western characteristics of entrepreneurship, was too dependent on guidance, emphasized an all-round development of personality to harmonize with the environment, which discouraged aggressiveness and encouraged traditionalism, rather than modernization [27]. However, Tu suggested that individualism is a Western mode of capitalism and East Asian had developed another model based on relationships to develop change through consensus and networks, with a sense of personal discipline [28]. Confucianism was criticized for lack of profit motive, as his philosophies discouraged self-motivation and that merchants were not included in Confucius set of key relationships. However, through responsibility and obligation to family, other motives exist, such as their well-being [29], and treatment of those inside and outside an individual’s universe of relationships will be different, i.e., outsiders treated with respect but caution, more adversarial, rather than brotherly relationship. Confucianism is also criticized for its lack of innovation, whereas the reality of Chinese business has been to seek ways to control an existing market, rather than create new value through innovation [30].

The tremendous economic growth in Asia after the Second World War was labelled as ‘Confucian capitalism” [31]. Hofstede postulated that culture is a prime determinant of performance and Confucianism dictates hierarchical organizational structure, preserving values, and thrift, which were all seen as organizational drivers of economic growth [32]. One of the side effects of Confucianism is nepotism and thus the creation of lack of transparency, corruption, and inefficiency [33]. Some scholars labelled this as one of the prime reasons of the 1997 Asian financial crisis [34][35].

Perhaps one area where Confucian concepts can be superficially seen is in the Chinese family business around Southeast Asia. Chinese family businesses are usually run by a patriarchal leader who installs direction and morals through the exercise of Confucian virtues [36]. However, this often degenerates into crude authoritarianism [37]. The hierarchy usually follows a kinship structure where one’s position depends upon relationship with the leader, rather than on any professional merit. Subordinates know their roles and operate within a certain degree of autonomy, although most organizational knowledge is monopolized by the leader and shared at his discretion [38]. Personal relationships are thus very much part of the decision making process and organizational performance is very subjective. Performance of these enterprises is often sub-optimal because of the nepotistic nature of organizations. In addition, one of the major objectives is to maintain harmony and avoid conflict within the organization as a means to maintain stability.

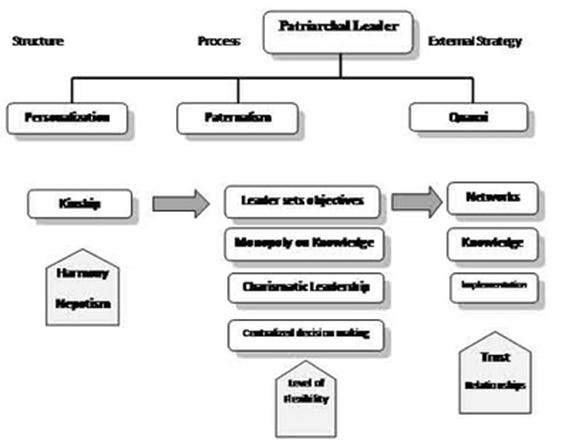

Human relationships are built upon trust based on the principles of personalization and quanxi [39]. This was necessary in developing Southeast Asia when legal codes and contractual enforcement were still in their infancy. The effect of these arrangements was to slow down the state of progress and limit the incorporation of newcomers to an industry. This also restricted the input of new ideas and technology into firms within the region. The overview of a traditional Chinese family enterprise is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1. The Traditional Chinese family Business

In theory the centralization of decision making increases the ability to make quick decisions and adapt to a changing environment. However, leadership in these organizations seem to take on a conservative disposition and be averse to change. Firm flexibility and technology sophistication almost wholly depends upon the competencies of the patriarchal leader.

To the contrary, it can also be argued that Confucianism actually has little influence on the way Chinese business is operated, at least in South-East Asian countries like Malaysia. Although Chinese business sustains and nurtures family members and maintains a paternalistic and hierarchical nature of authority within the enterprise [40], there is little evidence that Malaysian Chinese businesses rely on guanxi networks for growth and development [41], have little interest in long term sustainability and little adherence to the Chinese philosophies associated with Confucianism [42]. It is also unlikely that many contemporary Chinese have a thorough understanding of the Confucius philosophy or the will or want to fulfil the piety and wisdom defined by Confucius in everyday life. One of Confucius followers Mèngzî warned, Ren is a concept not easily achieved by man. However modern life and business may tend to be judged by old values, creating a complexity of behaviour that is often hard to understand [43], especially by the older generation that is Chinese educated. With the new generation returning to their family businesses after overseas study there is great pressure for patriarchal leaders to step aside and/or allow the introduction of ‘more professional’ management. Perhaps the greatest influence of Confucianism is in the governance of the State of Singapore, rather than in business [44].

Finally, John Naisbitt in his prophecy book MegatrendsAsia predicted that the unique strengths of Chinese business networks, able to make speedy decisions and able to obtain resources through connecting people would make the Chinese business model the ideal flexible form of social organization for the globally connected world of the future [45]. However this would assume that harmony doesn’t exhibit restriction on individuals from criticism of strategy, even though it may be constructive, as the practice of authority in Chinese companies means obedience rather than careful questioning of the status quo [46].

The War (Sun Tzu) Paradigm

Sun Tzu’s The Art of War was written 2,500 years ago and was most probably the first comprehensive book of military strategy ever written [47]. Sun Tzu saw strategy as a tool in warfare, primarily out of sight of the enemy, aimed at gaining advantage and defeating an adversary by fighting as few battles as possible [48]. Sun Tzu postulated achieving victory by out-thinking and out-fighting the enemy with the best tools at one’s disposal. The thirteen chapters of the book lay out an ideology of strategy as follows;

Chapter One: The proper planning of strategy. Chapter Two: How to avoid protracted campaigns. Chapter Three: How to defeat the enemy without going to battle. Chapter Four: Find the enemies weaknesses. Chapter Five: How to exploit opportunities. Chapter Six: How events and strategy are unpredictable. Chapter Seven: Relief of the enemy’s vigilance. Chapter Eight: The adaptation of strategy. Chapter Nine: Exploring the enemy’s position. Chapter Ten: The diligence of a commander. Chapter Eleven: The obedience and submission of subordinates. Chapter Twelve: Diligence and caution when undertaking tasks. Chapter Thirteen: The use of intelligence.

Within the above chapters are six basic applications of the principles outlined in each chapter of the book. These include;

Winning whole or succeeding with all one’s resources and objectives intact. Leading to advantage or how to prepare and position soldiers for victory. Deception or keeping one’s intentions secret from opponents and enemies. Energy or applying force effectively and efficiently. Capabilities or finding the best path to achieve an objective, and Initiative or how to take advantage and capitalize upon an emerging opportunity in a conflict.

Perhaps the most important aspect of Sun Tzu’s doctrines is wisdom. In ancient Chinese the character for wisdom was similar to the character for knowledge, thus wisdom and knowledge are interwoven. Sun Tzu believed that wisdom was an innate quality of a general and is made up of four qualities, the ability to plan, perceptibility, predictability, and adaptability. Therefore, in planning a good general must know what the fight is for and how to place his troops and weapons in the right place at the right time. Potential problems must be foreseen, so that solutions are available when and if they are encountered. In addition, a general must be free of emotion so that decisions can be made without undue influence and consistently. Finally the general must be able to adapt to unexpected changing circumstances that may arise in the course of the campaign.

In chapter five of The Art of War, military tactics are equated with the flow of water. “As flowing water runs away from high places and speeds downward, an army avoids strengths and seeks weaknesses. As water shapes its course according to the ground, an army works out its victory in relation to the enemy it faces. Therefore, as water retains no constant shape, there are no fixed conclusions in warfare. He can modify his tactics according to the enemy’s situation and thereby succeed in winning, may he be called divine” [49].

Military strategy has influenced business strategy as it has a similar objective of achieving a desired result and winning. Some of the important principals of Sun Tzu’s strategies that can be seen as relevant to business are summarized below:

· Business is extremely important to the owner so thorough planning is necessary

· Avoid if possible direct competition against competitors (i.e., find a market where there is no competition).

· Emulate as much as possible the strengths of your competitors and build your strengths where your competitors are weak.

· Ensure you have a planned exit strategy if necessary.

· Know your competitors well, you will have a better chance of success

· Good leadership is a powerful motivator of followers (wisdom, sincerity, benevolence, courage, strictness).

· Show by example.

· Develop shared values in your organization to gain commitment.

· Develop competitive advantage and make full use of it in the marketplace.

· A powerful and efficient leader is indispensable to the success of the firm.

· Have a good technical background.

· To be competitive, a company must be able to capitalize on various changes in the economy, business and social environments and develop strategies accordingly.

· Must realistically understand what is in and outside of your control.

· Position yourself close to the resources you need and markets.

· Strength is a relative concept, no absolute superior or inferior strength, it is how you arrange your resources that can bring success.

· Hide your strengths and weaknesses from your competitors so you have the element of surprise in the marketplace.

· Seek out as much information about your competitors, markets and customers as possible.

· Delegate subordinates with enough authority to get the job done.

· Training is an important method of achieving efficiency.

· A combination of benevolence and strictness is the key to guaranteeing loyalty of your staff, and,

· Be transparent in your reward systems so employees know what they will receive.

An element that is beginning to be regarded as an important trait in entrepreneurship is courage [50]. Sun Tzu mentioned courage in chapter eight describing a general as a person who must be brave and courageous in battle, and his troops if cowardly will face capture by the enemy. In addition, a general must be prepared to be bold and take calculated risks when necessary, in order to seize opportunities without hesitation. Courage should also be attached to resourcefulness and decisiveness. Courage runs in two directions. If a situation becomes hopeless, a general must recognize this and immediately make a retreat. The courage to move forward blindly, i.e., making decisions based upon courage alone, is not genuine courage but a delusion, something equated to what we recognize as an overconfidence bias [51].

Many authors writing about Asian business attribute Chinese business success to the following of the doctrines of Sun Tzu [52]. This may have some positive bearing in the business strategies of some businesses, which are quoted as examples in books [53], and Sun Tzu’s philosophies have certainly influenced writers[54]. But as other authors have commented in the Asian SME context, most businesses start out finding the correct business strategies by nothing more than trial and error until they find the winning set of strategies for their businesses [55]. Very few business entrepreneurs in Southeast Asia until recently have been educated past secondary school and although Sun Tzu is known to Western business scholars, it is highly doubtful whether many are familiar with his works on strategy. However, there is some evidence that the educated Chinese public service over the centuries did use these texts in forming the strategies of Chinese state [56]. It appears that the doctrines of Sun Tzu were studied by Western military scholars [57] and the early business schools took some interest in The Art of War in the 1950s and 60s when the concepts of business and corporate strategy was being pioneered. Strategy as a war paradigm became very popular in the United States with a number of ‘bestsellers’ like Barrie James ‘Business War Games’, and Al Ries and Jack Trout’s ‘Marketing Warfare’ [58] in the 1980s and has become part of contemporary marketing terminology [59].

Yet it is claimed that Sun Tzu’s doctrine influenced Admiral Yamamoto in planning the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Mao Tse-Tung’s philosophies, the Vietnamese General Vö Nguyên Giáp’s strategies that led to victories over the French and American forces in Vietnam, Che Gueverra’s revolutionary and guerrilla tactics in South America, and the Gulf war campaigns and resulting insurgencies [60]. In addition, Sun Tzu has become part of popular culture influencing films like the Star Wars Trilogy, Wall Street, The Sopranos (HBO), The Art of War, and Die Another Day. The influence of Sun Tzu on Asian business has probably been through these western influences, rather than direct knowledge and education in the region itself.

The Buddhist Paradigm

Buddhist Dharma originated on the Indian Sub-continent with the birth of Siddhartha Gautama back in the 6th century BCE. Buddhism spread through South Asia, South East Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia, taking on many forms and variations, which include the Theravãda, Mahãyãna, and Vajrayãna traditions. Today Buddhism directly influences about 10% of the world’s population, although some practice a mix of Buddhism, and Taoism, that may even take on some Hindu influences.

Within the Abhidhamma Pitaka, the last of three parts to the Pali Cannon(the scriptures of Theravãda Buddhism) are a number of texts concerning psychology, philosophy and metaphysics. The Abhidhamma Pitaka describes the structure of the human mind and perception with amazing accuracy to the accepted views of modern neuro-science. The mind is described as a continual conscious process or experience in the metaphor of a ‘mindstream’ (something similar to phenomenological psychology) [61].

Within Buddhist philosophy, consciousness and metaphysics are combined in the concept of Pratîtyasamutpada or dependent origination. This is where reality is seen as an interdependent timeless universe of interrelated cause and effect. A human’s existence is interwoven with the existence of everything else and the existence of everything else is interwoven with the human’s existence in a mutually interdependent way. Because this concept is past, present and future, everything in the universe is only transient and has no real individual existence.

A person’s perception continually ebbs and flows on a daily basis with changes in intelligence, knowledge and understanding, based on the type of emotions one feels and their individual strength, pull and intensity. This process makes a person happy, sad, excited, hesitant or anxious about people, things and events around them. One may feel angry, greedy, jealous, trusting, lustful, and confused all in one day. More often than not, we are not aware of the influence of our feelings upon how we perceive things and behave, as this process is partly sub-conscious [62]. Feeling is what drives a person, whether it is to seek shelter and food, clothing and medical care, love and sex, career and comfort, etc. This is a very important concept because it is only our ability to free ourselves from attachment and delusion about our sense of self and values unconsciously placed on others, will we be able to see the world as it really is, rather than what we wish it to be. In fact our view of self and existence is created through our clinging and craving which blinds us to the reality of dependent origination [63]. The wheel of Samsara, or suffering through life is the heart of the First Noble Truth of Buddhism, that there is suffering. Although the wheel of Samsara may appear esoteric, the messages are straight forward without the divinity of mystic gods. This is the concept of Samsara was adopted into Buddhism with the metaphors of gods, afterlife, and rebirth, widely accepted during those times. Much of this mysticism has been added to Buddhism through the influence of various cultures and institutionalization over time [64].

Buddhism is about transcending delusions and the patterns and pathways we are locked into, so human perception is clear and unbiased. This makes Buddhism an ethical philosophy of life, rather than a religion in strict terms [65]. According to Buddhist Dharma (theology), desire is a major part of our motivation and psych. Buddhism sees mankind living in a deluded reality caused by infatuation, attachment [66] and clinging to desire for objects and permanence in the world as the source of all suffering. The pathway to wisdom [67] is found through understanding ‘The Four Noble Truths’ which are;

1. Our delusions of self-cause our suffering, 2. Suffering is a fact of life resulting from our attachment to what we desire, 3. If we extinguish our attachment, we reduce our suffering, and 4. By following the ‘Eightfold Path’ and developing wisdom, we can alleviate our suffering.

The first Noble Truth is about our habitual relationship and attachment to anguish and craving, and how we relate to the events within our life. Do we embrace our emotions and mistake them for reality? Do we realize the consequences of our actions? The third Noble truth is the ability to let go of our attachment allows us to see other realities, not based on the bias of the ego-centric ‘I’ or ‘me”. If we can achieve this freedom from our emotions, we can make decisions without just guessing about the potential consequences of our actions – a true wisdom.

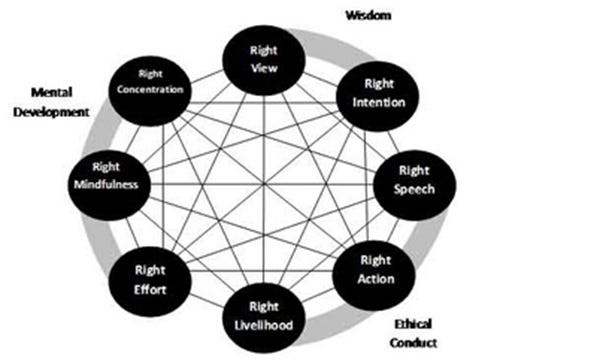

‘The Four Noble Truths’ can be seen as challenges to act rather than beliefs. Action as the fourth Nobel Truth espouses the practice of the ‘Eightfold Path’, which is a practical set of methods to let go of our attachment. The ‘Eightfold Path’ consists of right understanding, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, mindfulness and right concentration. Practice of the Eightfold Path may assist in raising consciousness to a completely non-dualistic view of subject and object. There is actually nothing spiritual or religious about the ‘The Four Noble Truths’ or ‘Eightfold Path’. The ‘Eightfold Path’ is about everything we do, a mode for being in this world. Such practice underpins the visions and ideas we develop. A depiction of the “Eightfold Path’ is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. A Depiction of the “Eightfold Path’

A brief description of each stage of the ‘Eightfold Path’ is below;

Right view is both the beginning and end of the path. Right view is about understanding the ‘Four Noble Truths’ and seeing true realities without the delusion of craving and attachment. With the Right view the see the imperfectness of our nature and that around us. We understand the Law of Karma [68] and dependent origination. Right view is the cognitive aspect of our wisdom or knowing, as our view of the world forms all intentions, thoughts and actions. It is an intuitive insight that all beings endure suffering and this can end with and understanding of the true nature of all things. Right view precipitates right thoughts and right actions.

Right intention is our mental energy that controls our actions – the ethical part of wisdom. Right intention is commitment to self development based upon our personal ethics. Without right intention our ethics are covered up by our emotions which overshadow our mental energy with emotional energy. Right intention involves resistance to desire, anger, aversion, cruelty to others, or aggression. Therefore, right intention is the source of our compassion.

Right speech is the first part of our ethical conduct within the ‘Eightfold Path’. Speech is considered very powerful and be as potent as action, therefore it is important to abstain from false speech, deceitfulness, slanderous speech, maliciousness, offensive or hurtful language to others, and idle chatter that lacks purpose. Right speech encourages a positive frame of telling the truth, speaking friendly, warm and gently, and only talking when necessary.

The second part of ethical conduct is Right action. Right action involves the body as a means of expression, and deeds that involve bodily actions. Poor action leads to ethical degeneration, while wholesome actions reinforce our sense of ethics. Right action is restraining oneself from harming other beings, especially the taking of life, taking what is not given, dishonesty, and sexual misconduct. In the positive frame Right action is about acting kindly to others, being compassionate, honest, respecting the belongings of others, and keeping sexual relationships harmless to others.

The third aspect of ethical conduct is Right livelihood. Right livelihood is about earning a living in a righteous way, where wealth is gained ethically, legally and peacefully. Dealing in weapons, dealing in living beings, i.e., raising animals for slaughter, the slave trade and prostitution, working in meat production and butchery, and selling intoxicants and poisons, as well as anything that violates Right speech and Right action should be avoided.

Right effort is the first aspect of mental development. This is a prerequisite for all the other elements along the path. Effort is an act of will which without, nothing can be achieved. Misguided effort leads one into delusion and negative Karma and confusion. Right effort depends upon our mental energy which can be positive producing self discipline, honesty, benevolence, and kindness, or negative producing desire, envy, aggression, and even violence. Right effort is necessary to prevent unwholesome occurrences, abandon unwholesome states that have already occurred, to arouse wholesome states that have not yet occurred, and maintain continuing wholesome states.

Right mindfulness is the preferred state of cognition. This is awareness that brings the ability to see things for what they really are – a high level of consciousness. Right mindfulness is both part of our perceptions and thoughts, to see beyond our stereotyped impressions and existing biases and patterning [69]. Through mindfulness one can control the way thoughts go and maintain wholesomeness. Four bases of mindfulness exist; contemplation of body, contemplation of feelings, contemplation of state of mind, and contemplation of phenomena.

The final principle of the ‘Eightfold Path’ is Right concentration. Right concentration refers to the development of focus in our consciousness. This can be enhanced through the practice of meditation.

In addition to the above Buddhist paradigm, other aspects of Dharma can also be developed into additional frames. These may include the concept of dependent origination which has influenced quantum and systems thinking, interpreting Samsara as organizational typologies in organizational development, and utilizing the concept of Karma in ethics and strategy.

There is very little evidence of direct influence of Buddhist Dharma upon business in Asia. Many studies mix Buddhist and Confucian philosophies which although bear some similarities, are also contrastingly different [70]. Although some cases are reported [71], the Buddhist business is more myth than reality. This is partly because there is very little consensus about what a Buddhist venture would actually be like (the author’s interpretation is only one possible interpretation). The only visible evidence is the belief and practice of a degenerated form of corrupted Buddhism, mixed with superstitious rituals, artefacts, ceremonies, giving donations to the temple for positive Karma, and praying to Bodhisatvta for wealth and prosperity.

However, Buddhist Dharma has influenced Western psychology significantly. The teachings of the Abhidhamma Pitaka have inspired and influenced many psychoanalysts and psychologists [72], including Carl Jung, Erich Fromm, Albert Ellis, Jon Kabat-Zinn and Marsha M. Linehan. There has been a great leap forward in humanitarian and transpersonal philosophical influence in therapy [73]. Dialogue between philosophy theorists and practitioners of East and West has led to mutually influential relationships between them [74]. This has led to new insights into therapies and new schools of thought on both sides [75]. Many of these practices are being used in modified forms for therapy today [76]. Aspects of Buddhist Dharma are also incorporated in the works of Western philosophers including Caroline A. F. Rhys David and Alan Watts.

Applying Buddhist philosophy to organization and management in “Western society” is also not new. Writers have focused upon the quantum analogies of Buddhism [77], ethics [78], and humanist views [79]. The wheel of Samsara provides insight that emotions play a major role in all organizations [80], where occidental organization theories have tended to ignore the role of emotion in organizations until quite recently [81].

The concepts of dependent origination through systems theory and a reframed ‘Eightfold Path’ is similar to many of the concepts within the learning organization. Peter Senge is the Director for Organizational Learning at the Sloan Business School at MIT in Boston. He was one of the high-profile academics during the 1990’s and propelled the concept of Learning Organization into the management vocabulary. Senge defines the learning organization “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together” [82]. Such organizations according to Senge will be able to face the rapidly changing environment with flexibility and adaptation, driven by peoples’ willingness and capacity to learn at all levels. However current organization structures and form are not conducive to learning and people although having great capacity to learn, do not have the tools needed [83].

Senge believes that people want to be part of something bigger than themselves to grow and this is where they have opportunities to ‘re-create’ themselves. The prevailing method of learning in organizations is adaptive learning focused on survival, but for a learning organization there must also be generative learning, organizational learning disabilities can be overcome. Generative learning requires a mastering of five disciplines;

· Systems thinking; seeing the world and events as a whole, where forces behind them are related. This helps us to see relationships and helps us to see how to change things effectively with minimum effort, i.e., to find leverage points in the system. This has a lot of similarities with the concepts of dependent origination.

· Personal mastery; the process of continually deepening and enriching our personal visions, the focusing of energies, developing patience and seeing reality objectively. Personal mastery could be considered a product of the ‘Eightfold Path’.

· Mental models; are unconscious metaphors of how we see things, which influence how we act. If we can understand how, we see things, we are in a better position to see reality more objectively. Mental models are about wisdom and right mindfulness.

· Building shared vision; to develop a shared picture which will create commitment, rather than just compliance by individuals. Building shared vision is about right intention, right action, right effort, and right concentration, and

· Team learning; is the ability of the group to rid themselves of their assumptions and begin to think together. This must be done openly without anyone trying to win. Team learning is about the journey that the ‘Eightfold path’ takes a community.

These disciplines can be focused towards seeing wholes, rather than parts, seeing people as active participants, rather than helpless reactors and to creating the future, rather than reacting to the past.

Senge and his team spent many years developing this process. However, companies found it extremely difficult to implement as managers were unwilling to give up power, management didn’t give enough flexibility and authority to staff, individuals weary about taking on the responsibility, managers and employees just simply didn’t have the skills and the process was undermined by organizational politics, something which is not directly tackled in Senge’s process. Learning organizations are fundamentally different from authoritarian organizations and it was beyond management to let go and make these radical changes. Learning organization is not a quick fix as many had assumed, but a daunting task requiring exploration of individual performance, personality and ambitions in life, something beyond many peoples’ willingness to make commitment. There are few organizations that resemble Senge’s model and while business wants to develop long term growth and stability, their focus is on enhancing brand recognition and status [84], intellectual capital and knowledge and product development and ensuring production and distribution efficiency [85], and solid financial returns [86]. There have been many suggestions that Senge’s model is just too idealistic and perhaps ahead of its time because of its revolutionary approach [87] and that it will take people to really make a commitment to organizational life in new ways. In 1994, Senge with his colleagues published the fieldbook [88] providing more ideas and suggestions about how to develop the process of learning organization.

For part 2 click on this link