Do Asian Management Paradigms Exist? A look at four theoretical frames. Part 2

Review of Contemporary Philosophy, Vol. 11, 2012, pp 92-124

The Islamic Paradigm

World events and media portrayal of Islam over the last few decades has projected negative images, which are based on a total misunderstanding of Islam and the principles it encompasses [89]. Predominantly, Islam through many eyes is seen as a homogenous view of the world, where many elements of the media have stereotyped [90] it as an extreme religion. This situation has not been assisted by the lack of published academic and intellectual thought [91], which could assist in developing more balanced views about what the principals of Islam stand for. The focus of most published works on Islamic economics and business has been in the domains of finance and morals [92], which leads most to the conclusion that Islam has little to contribute in the theories of economics and business.

The first and most comprehensive model of Islamic economy in modern times was published by Dr. M. Umer Chapra in the early 1990’s. His hypothesis was that existing economic models of capitalism, Marxism, socialism and the welfare state have failed to provide full employment, remove poverty, fulfill needs and minimize inequalities of income distribution. Both the market and centrally planned models have been weak in providing overall wellbeing, where problems of family disintegration, conflict and tensions, crime, alcoholism, drug addiction and mental illness have indicated a lack of happiness and contentment in the life of individuals. Dr. Chapra stated that a new system needs to be considered which could optimize human wellbeing and presented an Islamic model of economy, which never been tried or implemented in any world economy and has potential to solve common economic problems due to the overall humanitarian goal of achieving the wellbeing of all members of society [93].

The message of Islam forms its basis from the Al-Qur’an, which is the direct word of Allah (S.W.T.). The Hadĭths are documents made up of lessons taken from the life of the Messenger Muhammad (S.A.W.), written down by a number of apostles, which put the knowledge from the Al-Qur’an in both context in which they were revealed and assist in developing a general and universal significance [94]. Without the Hadĭths many important aspects of Islam would not be known today and the Al-Qur’an would be at the mercy of those who misinterpret it [95].

To date “The fanaticism and prejudice for Western managerial systems have also, among other things, veiled the relevancy of Islam as a model of management, as well as generating a cynical reaction that the Islamic model existed in history and concept only, but never practiced in modern life, even by countries with a Muslim Majority” [96]. Islamic scholars argue three main reasons for the need to develop and implement an Islamic business framework;

1. The nature of man: Man has both the potential to rise to great spiritual heights and also disintegrate into total immorality. Man’s ability to act rightly or wrongly is a matter of moral choice. Under the Islamic viewpoint, man’s purpose on earth to carry out ibadah (relates man to Allah {S.W.T} through spiritual acts) [97] and follow God’s will with total devotion, according to his natural disposition (fitrah); where everything fits into the divine pattern under the laws of Allah (S.W.T) [98]. Submission to the laws of Allah (S.W.T) brings harmony to man, however man was created with many weaknesses [99], forgetfulness [100], greed for material comforts and power [101], is capable of oppressiveness and ignorance [102], is rash and impatient [103], stringy and miserably [104], ungrateful [105], quarrelsome [106], ruthless [107], and full of self interest [108], which can easily lead him astray.

2. The amoral society: General society has become amoral and lapsed in faith, believing that truth and reality is based on what can be touched, smelled, seen, heard and tasted. This has led to a society that has become materialistic and less spiritual. This absence of spirituality is leading business into immoral activities such as stealing, lying, fraud and deceit, making people believe that they cannot succeed without pursuing the same practices [109].

3. The underdevelopment of Islamic societies: Approximately 80% of the World’s Muslins live in poverty, as cultural minorities in other countries, with high incidences of unemployment and low productivity [110]. Countries with majority Muslin populations, are declining in their knowledge generation, research, innovation and educational standards [111], have a generally a lower life expectancy, higher illiteracy rates, lower GDP per capita rates with the majority of people living in fragile and non-arable lands, poorer infrastructure and water supplies and a larger number of dependents than the non-Islamic World [112]. Islamic GDP as a percentage of total World GDP is estimated to be only 45% of what it should be, in order to be on par with the rest of the world [113].

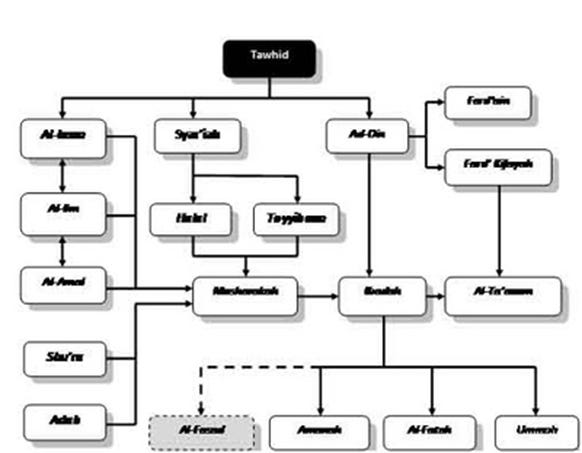

The basic Islamic principles and their interrelationships are shown in figure 3 below.

Figure 3: An Islamic Business Framework

The Al-Qur’an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad (SAW), who was born into a trading family and brought up by Abu Talib, who was a trader. Society in the Prophet’s time was almost totally dependent on trade as a means to earn a living and unlike any other religion, the Al-Qur’an is heavily written in the metaphor of business and trade. Within many parts of the Al-Qur’an life is paralleled to a business venture, where one earns profits to gain entry into heaven – profits meaning faith and good deeds to others and those that accept Allah’s (SWT) guidance as a bargain to save them from punishment on judgment day [114]. Islam urges individuals to strive their utmost to earn large monetary rewards and spiritual profits, while at the same time being inspired to be successful and honest people [115]. This is part of the concept of ad-din, which makes material and spiritual pursuits inseparable, where one’s whole life is concerned with the needs of humankind here on earth to secure a comfortable life in the Hereafter [116]. Consequently, Islam does not prohibit worldly success [117], in fact Allah (SWT) has provided opportunities for humankind to obtain success and it is certainly the responsibility of the individual to do so [118]. However involvement in business should also carry with it benevolent intentions for others while seeking success for oneself [119].

Islam espouses a market economy with freedom of the individual to operate a business with minimal outside interference;

“He who brings goods to the market is blessed with bounty, he who withholds them is cursed.”(Ibn Majah & Al Hakim)

A market mechanism is urged with free flowing knowledge without exploitation by middlemen;

“Do not chase after those who are going to the market before they reach the place.” (Al-Bukhari & Muslim)

Islam also prohibits price manipulation;

“Anyone who withholds goods until the price rises is a sinner.” (Muslim).

Thus Islam espouses that free trade is a major factor in the enhancement of living standards of the general community, subject to some constraints on business in the interests of the wider community.

Central to Islam is Tawhid “…a man’s commitment to Allah, the focus of all his reverence and gratitude, the only source of value. What Allah desires for man becomes value for him, the end of all human endeavour [120].”Tawhid is the Islamic way of life, the fundamental of all Islamic civilization, which is process, means and end together. Tawhid is both the essence of the individual and the society he or she lives in. Tawhid is acceptance of one creator and His divine guidance of humanity [121]. Tawhid implies both the mission and morality of humankind in both social and spiritual contexts.

Mankind’s responsibilities under Tawhid fall into two categories, fard’ain which is an individual’s obligation to perform his or her religious duties and fard kifayah, which is an obligation for man to serve the entire community, through services to each other, necessary for the community to live safely and comfortably. Thus the obligation to improve the Muslim Ummah (community) falls under fard kifayah [122], where undertaking business is the principal method [123] of improving the economy and community;

“Be involved in business as nine out of ten sources of income lie in business” (Ihya)

The building blocks of Tawhid are the concepts of al-iman (belief), al-ilm (knowledge) and al-amal (pious acts and efforts). Al-iman is the belief in the existence of one God and Creator, with a commitment to His teachings and revelations, revealed through the Al-Qur’an, and Prophets, through the Hadĭths and Sunnah (What the Prophet Muhammad (S.A.W.) said, did, agreed or disagreed to). Our faith in Allah (S.W.T.) is reflected in our daily behavour, influenced by our moral system formed and contained within us. It is our inner self;

“Faith is not expectations and not outward ornamentations, but implanted in the heart and realized through actions.” (Ibn Najjar & Dailami)

Al-iman is deepened by al-ilm [124], which is the responsibility of all Muslims to seek [125] in order to fulfill and perform al-amal. Knowledge (spiritual, wisdom and scientific) is the foundation of all acts of al-amal which would be futile and unproductive without the search for further knowledge [126] to enhance the wellbeing of society [127]. Islam places great importance on scientific discovery, knowledge and wisdom to develop civilization [128]. Al-iman and al-ilm manifested through al-amal is the basis of the advancement of civilization for the benefit of humankind and the Ummah (Muslim community), in particular. This is undertaken under the principal of ad-din, mentioned above, which is referred to as ibadah.

In Islam a person, who of faith, knowledge and pious devotion, manifested in effort and acts, using reason and experience and adheres to the teachings of the Al-Qur’an and Prophets is a person of Taqwa, adhering to the philosophy of Tawhid. He is fulfilling his purpose on earth to perform ibadah [129] to God, through obedience (ta’ah), which conforms to his true and essential nature (fitrah) of man. This relates man to God through everything an individual does, including spiritual duties, thoughts, actions and deeds to other people [130].

As man operates in a social environment, Islam prescribes a number of forms of business organization, through which his obligations can be fulfilled. A mushharakah can take a number of forms;

a) Mudarabah: Partnership where one manages the partnership and another supplies the financial support, b) Shirkah: where two or more individuals pool financial resources and share profit and loss on an agreed ratio and held liable to the extent of their capital, and c) Syari’ah: each partner is able to operate other businesses, independent of the principal business.

Such business organizations are founded and operated on the principal of al-ta’awun (mutual assistance and cooperation) among members of a society for both their mutual benefit and that of a society as a whole [131].

Islamic business is governed by the rules of syar’iah, the path by which all Muslims should follow. The syar’iah is the divine law that establishes the standards of justice and human conduct, as well as what is permitted and prohibited in action. The syar’iah is based on the Al-Qur’an, Sunnah and interpretations by Islamic scholars. Some Muslim scholars have stated that these standards are beyond human and are a goal or path of guidance [132], where others see these utopian ideals as mandatory for advancement of the community [133].

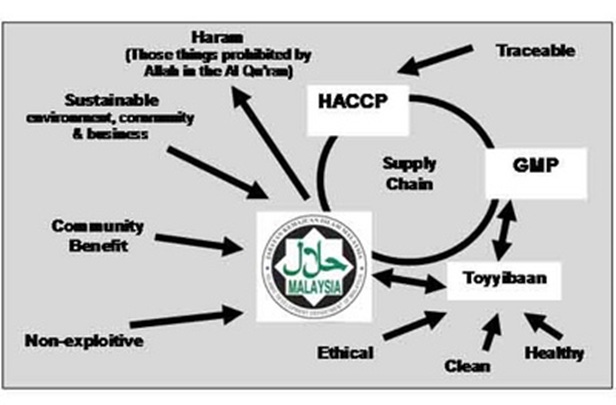

Central to the syar’iah are the concepts of Halal and Toyyibaan, which govern all the economic activities of man in wealth production and consumption of wealth, where certain means of gaining a livelihood are declared unlawful l[134]. Halal means lawful or permitted for Muslins [135], a concept that is much wider than just issues of food, concerning as to whether things are undertaken according to the syar’iah [136]. Toyyibaan is a much wider concept, meaning good, clean, wholesome, ethical in the Islamic concept. In nutrition, Toyyibaan is much wider than Halal, as food must also be clean, safe, nutritious, healthy and balanced [137]. Toyyibaan would also mean that agriculture must be undertaken within sustainable practices [138], and in business that things are done with good intentions [139].

Figure 4. The concept of Halal and Toyyibaan in relation to HACCP and GMP [140].

In Islam, the individual’s vision, mission and objectives in business is to achieve both success in this world and the hereafter. This is al-falah. Islam puts very little restriction upon the scale of worldly success [141], except specifying, it must be reasonable, provides the comforts of worldly life [142], with consideration to the poor and suffering [143], and within the balance of worldly and spiritual life [144]. Mans success must also serve the legitimate needs of the ummah [145]. This is in great contrast to the singular objective of profit maximization in contemporary business thinking [146].

Allah (S.W.T.) equipped man with the faculties of understanding right and wrong, so that he may obtain a bright destiny [147]. Man has a free choice in what he chooses. Opposition and straying from his true nature (fitrah) will bring discord to the individual where negative attributes will distort his true nature, which could lead him into doing evil deeds [148]. The individual has his al-iman and al-ilm to keep him from this path of self destruction (al-fasad), which would manifest itself through nepotism, favoritism, envy, greed, corruption, injustice and ignorance [149]. This in Islam is the influence of Satan, manifested in many different ways to man to lure him away from God’s chosen path for him. Man becomes unfocused through ignorance and lack of knowledge [150].

Achieving al-falah means that man has lived up to God’s trust placed upon him, through performing his ibadah, while obeying all the laws of the syar’iah. This is where man has overcome his weaknesses in the service of Allah (S.W.T.) through righteous deeds (amal), in his obligation of fard kifayah. Man has reached the state of amanah, fulfilling the trust God has put in him [151].

Islam also specifies the way organizations should be operated and managed. As discussed, an organization must base all its work on al-amal and ibadah with the overall management objective of achieving al-falah for the organization as a whole and each individual within it. This is based upon a foundation of al-iman and al-ilm, within a civilization based upon a Tawhid philosophy, so that employees have the opportunity to achieve taqwa and avoid straying towards the state of al-fasad. Central to achieving this are the concepts of shura (participation in decision making and community learning) and adab (justice and rights).

Shura is total organizational community participation in decision making to ensure an organization gets the best views, is creative, to develop employees understanding of decisions made, to achieve better implementation of decisions and strengthen the Islamic fraternity [152]. Shura is can also be seen as a organizational control mechanism to prevent management and individuals within the organization from straying down the path of ignorance, greed and oppression [153], so that the organization can continue to serve its members and the wider community and thus sustain itself. Shura creates a positive learning environment within an organization, similar to the concepts of a learning organization postulated by Peter Senge [154]. The Al-Qur’an states that the concept of shura is mandatory upon any organization [155].

An organization should build its foundations upon the basic principles of human rights in its administration based on the concept of adab.Adab is based on the existence and recognition of Allah (S.W.T.) and recognition of his commands and laws (syar’iah). Within an organizational context, adab persuades man to do good and avoid evil (al-fasad), in accordance with the nature of man (fitrah) and nature of his action (al-amal). Adab comprises four major responsibilities, 1. responsibility to God, 2. responsibility to oneself, 3. responsibility to society and other human beings, and 4. responsibility to the universe and other creatures [156].

Over the last few decades ‘Western’ management ideas and ethics have moved closer to Islamic principles and ethics. Stephen Covey, a devout practicing member of The Church of Latter-Day Saints, evangelistically preaches personal development, fulfilment and spirituality within the context of the organization. Covey’s first book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective people set a standard of highly ethical and humanistic principles that all individuals should strive for in business [157];

· Be proactive as this will develop the ability to control one’s environment, rather than be controlled by it, as is generally the case.

· Begin tasks with the end result in mind, avoid distractions and concentrate only on relevant activities, which will make you much more productive,

· Organize correctly and undertake the most important tasks first in a step-by-step approach,

· Look for win-win strategies so that all benefit,

· Listen to people first and understand them before you try to make them understand you, which will assist in maintaining positive relationships with people,

· Look to develop synergy between people which will develop a better outcome, greater than what individuals can achieve working by themselves, and

· Continually seek self-renewal, spiritually, mentally, emotionally, socially and physically.

Covey’s book sold over 15 million copies and launched him on a career of consulting to many of the top Fortune 500 companies. Covey built a training and consultancy company which has over 12,000 direct facilitators with curriculum materials translated into numerous languages. Covey’s organization has also developed pilot programs with cities wishing to become principle centered communities. Covey’s set of life rules is not without their critics who claim his ideals are too idealistic and difficult to implement as well as being seen as a quick fix approach. However, this does not detract from the extremely large following of devotees to Covey’s methods growing around the world. There are similarities with Peter Drucker, Dale Carnegie and David Allen in the approach. Dale Carnegie’s work is also on the rise again in popularity and consequently, corporations are taking notice of the importance of employee personal growth within the corporate environment.

The above ‘Western’ management ‘gurus’ have had great impact upon the corporate world and way management is taught at business schools. In the world where 20% of the population follow Islam, there is little evidence that Islamic management principles are practiced in Islamic countries of South East Asia. Ironically, unlike the ‘West’, Islamic Scholars, in agreement with Dr. Umer Chapra’s observations have not agreed due to various interpretations of Islam to a universal Islamic business model for the Islamic World to embrace and espouse. ‘Western’ management scientists have taken the initiative on similar principles that were laid down in the Al Qu’ran and Hadiths, more than 1500 years ago.

Commercially, the Islamic model is increasing in importance today. There is a growing awareness among Muslims about their duties and responsibilities to adhere to the Tawhid. As Muslim consumers require more Islamic goods and services [158], Islamic compliant supply chain development is a major growth industry in itself, and is becoming a feature within conventional supply chains internationally. The concepts of Halal/Toyyibaan are compatible with GMP/HACCP, and also incorporate a strong ethical framework that is consistent with the rapidly growing global ‘ethical product’ and ‘Fairtrade’ movements [159]. However how many ‘Islamic corporations’ on the ground are actually complying with Islamic principles, other than Halal certification remains an interesting area for future research. Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand are developing Halal food hubs without taking into consideration the underlying Tawhid principles to make these proposed hubs holistic in their approach to Islamic business.

Conclusion

The relevance of any paradigm to business and management depends upon the meaning and inspiration it provides, rather than the scientific validity. Scientific validity is not really very important as long as management ideas capture the imagination and promotes action. This can be seen by the management thinking arising in the 1990s within the US which inspired the ‘battle cry’ against the oriental onslaught at the time.

Our sojourn through four Asian paradigms superficially shows that in contemporary society, each paradigm has probably more influence in ‘Western’ management thought than in Asian management thinking. The only probable exception is Confucianism which could cautiously be associated with the structure, process, and strategies of family owned Chinese businesses in Southeast Asia. However even the influence of this paradigm is declining as ‘occidental management paradigms’ learned by ‘Gen Y’ children of patriarchal leaders return home from study abroad with new ideas. Yet this does not mean the disappearance of Confucianism as an influence on management as the cognitive and ethical aspects may enjoy a renaissance in China this century [160].

This is the challenge to management academics and practitioners in the Asian region. It is the task of looking locally through the rich history, culture, society, stories, and philosophies of the region for inspiration to develop and construct ‘homegrown’ management ideas, rather than importing ideas developed in other parts of the world, which are suitable for those parts of the world. Confucian, Buddhist, Strategy, and Islamic institutes of thought exist all over the region, but there has been little focus on developing these philosophies as management paradigms. Today there is an intense vacuum of original management thinkers in the Asian region.

Although Sun Tzu’s ‘The Art of War’ and Buddhist Dharma originated in the Asian region, it has primarily been ‘Western’ management thinkers who have applied the respective philosophies to management, at least in these contemporary times. Although the Islamic ‘Tawhid’ is 1500 years old, it is probably only now that it is being considered seriously as a management philosophy. Before now, Islamic thought has had negligible influence on contemporary business, but the market may change that, although Islamic society itself has not taken Islamic concepts onboard into business until this time. The nature of Muslim consumers and the rapid growth of the Halal market globally will be a driver of change here.

The paradigms discussed in this paper intellectually, philosophically, and practically have a lot to add to the development of ethical business, human relations, conflict management, organizational learning, and even creativity development. Using each paradigm as a metaphor assists us understand the paradoxes and contradictions of business in the Asian environment. One of the issues is interpretation. Max Weber interpreted Confucianism as a negative force to economic growth and William Ouchi probably understated the influence of Confucianism in Japanese business hierarchy and decision making. Using a single metaphor provides a biased insigh t[161], but when multiple metaphors are used, we can see that something may have various layers of meaning.

Finally, the author could have selected other paradigms that have influenced business and management in the Asian region. For example the Taoist traditions probably have an important influence on Chinese cognition in Southeast Asia [162], and Hinduism heavily influences society and the nature of business in South Asia [163]. In addition, there are a number of other frames that can be utilized to elicit meaning. Such paradigms as ‘feudalism’, ‘developing nation’, ‘government sponsored capitalism’, ‘crony capitalism’, ‘cowboy entrepreneurship’, ‘adventurism’, ‘Sufism’, ‘Sikhism’, ’Shinto traditions’, ‘Machiavellism and diplomacy’ etc, can bring new layers of meaning. These can be built up into relevant meta-theories and interchanged to shed more understanding of the dynamics of Asian business and economy.

For part 1 click on this link

Notes and References

[1] The Japanese success was not a sudden one. Faced with a completely destroyed economy in 1945, language difficulties, lack of resources, and a reputation for poor quality goods, the Government, business and banks worked on long term strategies to reestablish Japanese industry.

[2] Kotler, P., Fahey, L., & Jatusriptak, S. (1985), The New Competition: Meeting the marketing challenge from the Far East, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice/Hall International.

[3] Ohmae, K. (1982), The Mind of the Strategist: The Art of Japanese Business, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[4] Schonberger, R., J. (1982), Japanese manufacturing techniques: Nine hidden Lessons in Simplicity, New York, Free Press.

[5] Pascale, R., T. & Athos, A., G., (1982), The Art of Japanese management: Applications for American Executives, New York, Warner Books.

[6] Ouchi, W., (1982), Theory Z: How American Business Can Meet the Japanese Challenge, New York, Avon Books.

[7] Ouchi, W. (1984), The M Form Society: How American teamwork Can Capture the Competitive Edge, New York, Perseus Books.

[8] Morita, A., (1987), Made in Japan: Akio Morita and Sony, London, William Collins & Co. Ltd.

[9] Backman, M. (2004), The Asian Insider: Unconventional Wisdom for Asian Business, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

[10] Studwell, J., (2007), Asian Godfathers: Money and Power in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, New York, Grove Press.

[11] Lasserre, P., & Schūtte, H., (1995), Strategies for Success in Asia Pacific: meeting New Challenges, New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

[12] Krugman, P., (1994), The Myth of Asia’s Miracle, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 73, No. 6, pp. 62-78.

[13] See for example: Engardio, P., (2007), China: How China and India are Revolutionizing Global Business, New York, McGraw-Hill, Yang, K. (2007), Entrepreneurship in China, Aldershot, Ashgate, and Nie, W., Xin, K., & Zhang, L. (2009), Made in China: Secrets of China’s Dynamic Entrepreneurs, Singapore, John Wiley & Sons.

[14] Rarick, C., A., (2007), Confucius on management: Understanding Chinese Cultural values and management Practices, Journal of International Management Studies, Vol. 2, No. 2, Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1082092

[15] There are so many texts about Sun Tzu. One of the author’s favorites is Sawyer, R., D., (1994), Sun Tzu: The Art of War, Bolder, Westview Press.

[16] Witten, D., & Rinpoche, A., T., (1999), Enlightened management: Bringing Buddhist Practices to Work, South Paris, ME, Park Street Press.

[17] Dr. Chapra in an on-line interview was very critical of the development of Islamic economic and business theories claiming they were unbalanced in their approaches. He was reported to state that “Primary attention has been given so far to Islamic Finance. This has led to the false impression that interest-free finance is all that Islamic Economics has to offer. Since most of the governments in Muslim countries are not yet convinced that interest-free finance is workable, excessive emphasis on it has created a resistance in official circles against Islamic Economics. They find it to be of little value. This is unfortunate. We must blame ourselves for this. Islam is a complete way of life and is capable of solving the problems of not only Muslim countries, but also of mankind”. In the same interview Dr. Chapra said that it was the responsibility of Islamic intellectuals to show how Islamic economics could solve the socio-economic problems that humankind faced. This is in great need because there is a distinct lack of theoretical and empirical analysis to show that an Islamic strategy can help solve economic problems, particularly with the current state of the Islamic world, where there is decline in moral values, exploitive financial systems, illegitimate governments, landlordism, lack of education, absence of justice and ineffective operation of incentives and deterrents. Dr. Chapra believes that there is great repetitiveness in what is written about Islamic economics which is not serving any cause. An Islamic alternative needs to be spelt out, which can only really be done after the real position in Islamic countries is analysed, i.e., how individuals, families, firms and governments actually behave, so the gap between ideals and reality can be measured and Islamic remedies developed. See: Islamic Voice, ‘Islamic Economics Offers the Best to Mankind’, http://www.islamicvoice.com/june.2003/ine.htm, (Accessed 20th December 2006).

[18] Oh, T., K., (1991), ‘Understanding Managerial Values and Behaviour Among the Gang of Four: South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong, Journal of management, 10, (2), pp. 46-56.

[19] Meyer, M., W., (1994), China: A Concise History, 2ndEdition, Littlefield Adams.

[20] Chen, M., J., (2001), Inside Chinese Business: A Guide for Managers Worldwide, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, P.89.

[21] Chen, M., J., (2001), ibid., P. 21.

[22] Chen, M., J., (2001), ibid., P. 47.

[23] Koller, J., M., (1984), Oriental Philosophies, New York, Macmillan.

[24] Romar, E., (2004), Managerial Harmony: The Confucian Ethics of Peter F. Drucker, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 51, No. 2, pp. 199-210.

[25] Low, S., P., (2001), Asian Wisdom for Effective Management: From Lao Tzu to Miyamoto Musashi, Kuala Lumpur, Pelanduk Publications, P. 9.

[26] Backman, M., (2001), Asian Eclipse: Exposing the Dark Side of Business in Asia (Revised Edition), Singapore, John Wiley & Sons.

[27] Chen, M., J., (2001), Inside Chinese Business: A Guide for Managers Worldwide, Boston, Harvard Business School Press, P. 23.

[28] Tu, W., M., (1984), Confucian Ethics Today: The Singapore Challenge, Singapore, Federal Publications.

[29] Tu, W., M., (1995), ‘Is Confucianism Part of the Capitalist Ethic?’, Stackhouse, M., C., (Ed.), On Moral Buwsiness, Grand Rapids, MI., William B. Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 409-411.

[30] Fairbank, J., K. and Goldman, M., (1998), China: A New History, Cambridge, MA., Belknap Press of Harvard University.

[31] Tu, W., (1991), A Confucian Perspective on the Rise of Industrial East Asia, Confucianism and the Modernization of China, Mainz, Hase & Koehler Press, P. 31.

[32] Hofstede, G., (1991), Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind, London, McGraw-Hill, Franke, R., Hofstede, G., & Bond, M., (1991), Cultural Roots of Economic performance: A Research Note, Strategic Management Journal, Special issue, Global Strategy, pp. 165-166.

[33] Redding, S., (1993), The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism, New York, Walter de Gruyter.

[34] Pye, L., (2000), Asian values: From Dynamos to Dominoes?, Culture matters: How Values Shape Human progress, New York, basic Books., Seong, H., C., (2003), myth and reality in the Discourse of Confucian Capitalism in Korea, Asian Survey, Vol. 43, No. 3, P. 485.

[35] However another explanation is that institutions are more a product of their stage of development rather than the cultural context, which negates the Confucian influence. See: Singh, K., (2007), The Limited Relevance of Culture to Strategy, Asian Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 24, P. 421.

[36] Neelankavil, J., Mathur, A., & Zhang, Y., (2000), Determinants of managerial performance: A cross-cultural comparison of the perceptions of middle-level managers in four countries, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 31, No. 1, P. 121.

[37] Seong, H., C., (2003), Myth and reality in the discourse of Confucian capitalism in Korea, Asian Survey, Vol. 24, P. 485.

[38] Westwood, R., (1997), Harmony and Patriarchy: The Cultural basis for ‘Paternalistic Headship’ Among Overseas Chinese, Organizational Studies, Vol. 18, No. 3, P. 445.

[39] Redding, G., (1995), Overseas Chinese networks: Understanding the Enigma, Long Range Planning, Vol. 28, No. 1, P. 61.

[40] Weidenbaum, M. and Huges, S., (1997), The Bamboo Network: How Expatriate Chinese Entrepreneurs are Creating a New Economic Superpower in Asia, New York, Free Press.

[41] In actual fact rival Chinese businesses actually compete aggressively against each other in many markets and industries today.

[42] Gomez, E., T., (2004), ‘De-essentialising Capitalism: Chinese Networks and Family Businesses in Malaysia’, NIASyntt, No. 3., pp. 8-10.

[43] Bede, H., (1992), Understanding the Asian Manager: Working with Movers of the Pacific Century, North Sydney, Allen and Unwin, P. 10.

[44] Khan, H., (2001), Social policy in Singapore: A Confucian Model? New York, World bank Institute, available online at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/WBI/Resources/wbi37165.pdf, Lele, A., (2004), State Hindutva and Singapore Confucianism as responses to the Decline of the Welfare State, Asian Studies Review, Vol. 28, pp. 267-282.

[45] Naisbitt, J., (1996), Megatrends Asia: Eight Asian Megatrends that are Reshaping Our World, New York, Simon & Schuster, P. 24.

[46] Backman, M., (2001), op. cit., P. 18.

[47] Sun Tzu is believed to have been the author of The Art of War but accounts differ on the time he served as a general. Some accounts place him between 722-481 BCE, while others place him around 476-221 BCE. See Sawyer, R., D., & Sawyer, M-C., (2007), The Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, New York, basic Books, pp. 421-422.

[48] Sawyer, R. D., (1994), op. cit.

[49] Low, S., P., (2001), op. cit., P. 44.

[50] Hunter, M. (2012), Opportunity, Strategy, & Entrepreneurship: A Meta-Theory, Vol. 2, New York, Nova Scientific Publishers, P. 134.

[51] Hunter, M., (2012), ), Opportunity, Strategy, & Entrepreneurship: A Meta-Theory, Vol. 1, New York, Nova Scientific Publishers, P. 312

[52] Min Chen, (2004) Asian Management Systems, 2ndEdition, London, Thomson.

[53] Chen, M., J., (2001), op. cit.

[54] Ohmae, K., (1990), The Borderless World: Power and Strategy in the Interlinked Economy, London, Collins.

[55] Gomez, E., T., (2004), op. cit.

[56] Tung, R., L., (2001), Strategic management Thought in East Asia, In: Warner, M., Comparative Management: Critical perspectives on Business and Management, Vol. 3, London, Routledge,

[57] McNeilly, M., R., (2001), Sun Tzu and the Art of Modern Warfare, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 6-7.

[58] James, B., G., (1986), Business Wargames, London, Penguin, and Ries, A., & Trout, J., (1986), Marketing Warfare, New York, Paperback,

[59] Terms such as offensive, defensive, flanking, and guerrilla marketing strategies have become very common in marketing expression.

[60] Cantrell, R., L. (2003), Understanding Sun Tzu on the Art of War, Arlington, VA, Centre for Advantage.

[61] The early concept of phenomenology was developed by G.W.L. Hegel, who was interested in exploring the phenomena of conscious experience. These concepts were further developed by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, later enlarged upon by numerous philosophers including Franz Brentano, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Max Scheler, Edith Stein, Dietrich von Hildebrand and Emmanuel Levinas. Phenomenology looks at the consciousness as a process of experience rather as a static state. Consciousness is seen as a continual process where something is always in view, whether it be a perception of an object, event or fantasy. Therefore to consciousness it is not important whether the object is real or imaginary – the conscious intention exists of the object. In phenomenology the truth is what is intelligible based on one’s subjective opinion rather than physical reality. The perceived reality comes from the individual’s emotions, which are within the consciousness. The consciousness exists in the lifeworld, which in addition to the physical world includes all life experiences and memories. Some view the world as being completely transparent before the consciousness.

[62] Tashi Tsering, Geshe (2006). Buddhist Psychology: The Foundation of Buddhist Thought, Vol. 3, Somerville, MA., Wisdom Publications, P. 46.

[63] Dependent origination is a concept describing interrelatedness. It is represented on the other wheel of Samsara in the twelve states of ignorance, mental formation, consciousness, name and form, the six senses, contact, feeling, craving, clinging, becoming, birth and old age, and death. The state of our being and evolution is based on cause and effect. Through this journey our actions have consequences which bring recurring suffering, i.e., action brings suffering and suffering leads to action, in a reciprocal relationship of interdependence we are locked into. Through dependent origination we become locked into patterns like the metaphor of the channel of a stream being embedded and becoming a fixed feature of the geography of an area. This is becoming, a creation of our previous actions which makes up the elements of our personality.

[64] Batchelor, S., (1997), Buddhism without beliefs: A contemporary guide to awakening, New York, Penguin, P. 4.

[65] Watts, A, (1996). Buddhism the Religion of No-Religion: The edited transcripts, Boston, Turtle Publishing.

[66] Attachment in Buddhism is a much wider concept than attachment in psychotherapy where it is primarily concerned about infant/caregiver relationships in early life. Although there are many similarities, the two concepts should not be confused

[67] Wisdom in Buddhism can be interpreted as acceptance of Karma and conscious awareness of those actions that will bring us happiness and those that will bring us suffering and the understanding of the concept of non-duality, recognizing that there is no permanence.

[68] Karma is the law of cause and effect in relation to our mind, speech and actions, i.e., moral causation. New karma is continually generated through our ‘mindstream’ and is kept within us like a storage bank. Karma can be good or bad depending on the nature of the actions. Our stored karma determines how we perceive and respond to stimuli in the world. These are considered our natural or intuitive responses.

[69] Hunter (2012), op. cit. Vol. 1, pp. 22-23.

[70] Weber, J. (2009), Using Exemplary Business Practices to identify Buddhist and Confucian Ethical value Systems, Business and Society Review, Vol. 114, No. 4, pp. 511-540.

[71] Prayukvong, W., (Undated), A Buddhist Economic Approach to a Business Firm: A case Study, accessed at http://www.eco.ru.ac.th/eco/necon6/papers/g3/3.4.pdf (16th March 2012).

[72]Trungpa, C. (1975). Glimpses of Abhidharma: From a Seminar on Buddhist Psychology, Boston, M.A., Shambhala Publications, de Silva, P. (1991). Buddhist Psychology: A review of theory and practice, Current Psychology: Research and Reviews, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 236-254, Claxton, G. (1990), Meditation in Buddhist Psychology, In: West, M. A. (Ed,), The Psychology of Meditation, Oxford, Clarendon Press, Epstein, M. (1995) Thoughts Without a Thinker: Psychotherapy from a Buddhist Perspective, New York, Basic Books.

[73] Goleman, D. (2004). Destructive emotions and how we can overcome them: A dialogue with the Dalai Lama, London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[74] Safran, J. D. (2003). Psychoanalysis and Buddhism as cultural institutions, In: Safran, J. D. (Editor), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An unfolding dialogue, Boston, Wisdom Publications, pp. 1-34.

[75] Grossman, P, (2004). Mindfulness Practice: A unique Clinical Intervention for the Behavioral Sciences, In: Heidenreich, T., and Michalak, J., (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance in Psychotherapy, Berlin, DVTG Press, pp. 16-18, Safran, J. D. (2003). Psychoanalysis and Buddhism as cultural institutions, In: Safran, J. D. (Editor), Psychoanalysis and Buddhism: An unfolding dialogue, Boston, Wisdom Publications, pp. 1-34, Sherwood, P. M. (2005). Buddhist Psychology: Marriage of Eastern and Western Psychologies, www.sophiacollege.com/publications/Buudd%20pschoz.pdf, (accessed 20th October 2009).

[76] Epstein, M. (2001). Going on Being, New York, Broadway Books.

[77] Low, A., (1976), Zen and the Art of Creative Management, New York, Playboy Paperbacks.

[78] Field, L., (2007), Business and the Buddha: Doing well by doing good, Boston, Wisdom Publications.

[79] Larkin, G., (1999), Building a Business the Buddhist Way, Berkeley, Celestial Arts.

[80] Hunter, M. (2012), op. cit. Vol. 1, pp. 255-271.

[81] One of the first books on Emotions within organizations was: Fineman, S. (Ed.), (2000), Emotions in Organizations, London, Sage.

[82] Senge, P., (1990), The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of The Learning Organization, New York, Doubleday, P. 3.

[83] Ibid. Ch. 2.

[84] Klein, N., (2001), No Logo, London, Flamingo.

[85] Leadbeater, C., (2000), Living on Thin Air: The New Economy, London, Penguin.

[86] Hutton, W., (1995), The State We’re In, London, Jonathan Cape.

[87] Van Maurik, J., (2001), Writers on Leadership, London, Penguin.

[88] Senge, P., Roberts, C., Ross, R., Smith, B. and Kleiner, A., (1994), The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization, London, Nicholas Brealey.

[89] Hafez, K., (2000), ‘The West and Islam in the Mass Media: Cornerstones for a New International Culture of Communication in the 21st Century’ Discussion Paper C61, Centre for European Integration Studies, Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms-Universatät, Bonn.

[90] Policy Bulletin, (2005), The US Media and the Muslim World, Atlanta, GA, The Stanley Foundation, January 13th. (Accessed at www.stanleyfoundation.org, 19th December 2006).

[91] Hassan, R., (2006), ‘Islamic world faces intellectual stagnation’, Asia News Network,http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2006/11/04/opinion/opinion_30018026.php, (accessed 6th November 2006).

[92] Shams, R., (2004), ‘A Critical Assessment of Islamic Economics’, HWWA Discussion Paper 281, Hamburg Institute of International Economics, Hamburg, Germany.

[93] Chapra, M., U., (1990), Islam and the Economic Challenge, Leicester, UK., Islamic Foundation and Virginia, USA., The International Institute of Islamic Thought.

[94]Al-Qur’an (3:164)

[95] Koya, P.K., (Editor), (1996), Hadĭth ans Sunnah: Ideals and Realities, Kuala Lumpur, Islamic book Trust, Introduction xiii.

[96] Hassan, M., A., (1992), The Tawhidic Approach in Management and Public Administration: Concepts, Principals and an Alternative Model, Kuala Lumpur, National Institute of Public Management, pp. 6-7.

[97]Al-Qur’an (51:56)

[98]Al-Qur’an (30:30)

[99]Al-Qur’an (4:28))

[100]Al-Qur’an (20:115)

[101]Al-Qur’an (102:1-2)

[102]Al-Qur’an (33:72)

[103]Al-Qur’an (17:11)

[104]Al-Qur’an (17:100)

[105]Al-Qur’an (17:67)

[106] Al-Qur’an (18:54)

[107]Al-Qur’an (70:19-20)

[108]Al-Qur’an (4:128)

[109] Beekum, R., I., (1996), Islamic Business Ethics, Herndon, VA., International Institute of Islamic Thought.

[110] Mohsin, M., (1995), Economics of Small Business in Islam, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Visiting Scholar Research Series No. 2., Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Development Bank.

[111] Mehar, A., (2004), From Knowledge Creation to Economic Development: Missing Links in the Muslim World, Munich, Germany, MRPA Paper No. 358, http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/358/, (Accessed 19th December, 2006).

[112] Kahf, M., (2003), Sustainable Development in the Muslim Countries, , Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, IDB Prize Winners’ Lecture Series, Islamic Research and Training Institute, Islamic Development Bank

[113] Beal, T., (2006), The Global Islamic Economy: A rough estimate of the position of Islamic peoples in the global economy, paper presented to the Seminar on Islam And The Global Economy

Malaysian And Nz Perspectives, Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday 13th June. (http://www.vuw.ac.nz/~caplabtb/beal.html, Accessed 19th December 2006).

[114]Al-Qur’an (35:29), (26:207), (17:82).

[115]Al-Qur’an (2:164)

[116]Al-Qur’an (5:3)

[117]Al-Qur’an (2:168)

[118]Al-Qur’an (14:32-34)

[119]Al-Qur’an (24:37)

[120] Siddiqi, M., N., (2005), ‘Tawhid: The Concept and Process’, in Syed Agil, S., O. and Ghazali, A., (Eds.), Readings in the Concept and Methodology of Islamic Economics, Kuala Lumpur, CERT Publications, P.1.

[121]Al-Qur’an (2:170), (43:22-24), (7:28-29).

[122]Al-Qur’an (22:77)

[123]Al-Qur’an (2:275)

[124]Al-Qur’an (17:36)

[125]Al-Qur’an (92:4), (29:69).

[126] Hassan, M., A., (1992), op. cit., P. 24.

[127]Al-Qur’an (31:20)

[128]Al-Qur’an (35:28)

[129]Al-Qur’an (51:56)

[130]Al-Qur’an (2:21)

[131] Ismail, A., H., (1992), ‘Bank Islam Malaysia Bhd.: Principals and Operations’, in Sheikh Abod, S., G., Syed Agil, S., O., and Ghazali, A., (Eds.), An Introduction to Islamic Finance, Kuala Lumpur, Quill Publishers, P. 258.

[132] Doi, I., A., R., (1981), Non-Muslims Under Syar’iah, Lahore, Kazi Publications, P.4.

[133] Al-Buraey, M., A., (1988), Administrative Development: An Islamic Perspective, London, Kegan Paul International, P. 145.

[134] Chaudry, M., S., (2006), Social and Moral Code of Islam, Batu Caves, Selangor, Malaysia, Masterpiece Publications, P. 15.

[135]Halal-Haram Guide (2006), Penang, Consumers Association of Penang, P. 17.

[136] Amin, M., (1965), Wisdom of the Prophet Muhammad, Lahore, Pakistan, Sh. Muhammad Ashraf.

[137] Abdullah, A., and Huda, N., (2006), ‘Nutrition Security in Muslim Countries: The Drive Towards a Healthy Ummah’ in Saifuddeen, S., M., Mohd. Salleh, S., and Sobian, A., Food and Technological Progress: An Islamic Perspective, Kuala Lumpur, MPH Publishing, P. 173.

[138]Al-Qur’an (7:58)

[139]Al-Qur’an (5:5), (2:168)

[140] Hunter, M. (2009), Essential Oils: Art, Agriculture, Science, Industry, and Entrepreneurship: A focus on the Asia-Pacific region, New York, Nova Scientific Publishers, P. 670.

[141]Al-Qur’an (2:198)

[142]Al-Qur’an (7:31)

[143]Al-Qur’an (25:67)

[144]Al-Qur’an (22:77)

[145]Al-Qur’an (3:1-2), (4:125)

[146]Al-Qur’an (6:132), (16:97), (16:93)

[147]Al-Qur’an (90:8-10)

[148]Al-Qur’an (30:41), (103:1-3)

[149]Al-Qur’an (33:72)

[150]Al-Qur’an (2:169)

[151]Al-Qur’an (33:72)

[152] Hassan, M., A., (1992), op. cit., pp. 66-68.

[153]Al-Qur’an (42:36-40)

[154] Senge, P., M., (2006), The Fifth Discipline: The art and Practice of the learning organization (Revised and updated with 100 pages), London. Random House.

[155]Al-Qur’an (3:159)

[156] Lapidus, M., (1984), ‘The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam’, in Metcalf, B., D., (Ed.), Moral Conduct and Authority, Berkeley, Los Angeles, University of California Press, P. 39.

[157] Covey, S., R., (1990), Principal Centred Leadership, New York, Free Press.

[158] This is much wider than food and includes banking, finance, insurance, entertainment, tourism, and cosmetics, etc.

[159] Hunter, M. (2012), The emerging Halal cosmetic and personal care market, Personal Care, March, P. 40.

[160] Bell, D., A. (2006), China’s leaders rediscover Confucianism – Editorials & Commentary – International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Sept. 4, accessed online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/14/opinion/14iht-edbell.2807200.html (16th March 2012).

[161] Morgan, G. (2006), Images of Organization, (Updated edition), Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications, P. 4.

[162] Spencer-Rodgers, J., Peng, K., & Wang, L., (2010), Dialecticism and the Co-occurrence of Positive Emotions Across Cultures, Journal of Cross-Cultural psychology, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 109-115.

[163] Rai, H., (2005), The Role of Hinduism in Global India and Her Business Ethics, In: Capaldi, N., (Ed.), Business and Religion: a clash of civilizations?, Salem, MA, M & M Scrivener press, pp. 379-389.