Guest Editorial: The Batu Puteh Inquiry: A political controversy and questions of accountability

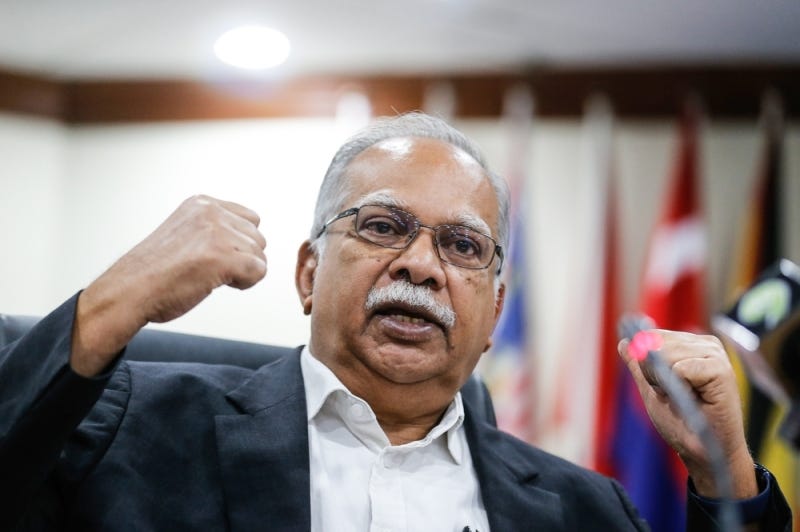

Prof. Dr. P Ramasamy

The Batu Puteh Inquiry: A political controversy and questions of accountability

The Royal Commission of Inquiry (RCI) into Malaysia’s handling of the Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks, and South Ledge sovereignty dispute has stirred significant debate since its declassification by the Madani government.

Although the report has been made public, 27 pages remain redacted, raising questions about transparency and the focus of the inquiry.

The report notably places blame on former Prime Minister Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad for unilaterally rescinding Malaysia’s appeal to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2018—a decision allegedly made without extensive consultation.

However, the findings and the selective focus on Mahathir have sparked controversy, with critics questioning the motives behind this narrative.

Mahathir’s decision to rescind the appeal

In 2008, the ICJ ruled on the sovereignty dispute over the three rocky outcrops between Malaysia and Singapore.

Batu Puteh was awarded to Singapore, while Middle Rocks went to Malaysia, and South Ledge’s ownership depended on territorial waters.

The judgment was binding, yet Malaysia filed for a review nine years later, during Najib Razak’s administration.

When Mahathir became prime minister in 2018, his government withdrew the appeal, citing legal advice and consultations with experts.

Critics, however, argue that Mahathir acted unilaterally and bypassed broader consultation, including opposition from the cabinet.

A collective decision or political targeting?

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has expressed visible frustration over the report, accusing Mahathir of dereliction of duty.

Yet, questions arise:

1. Cabinet Responsibility: If the withdrawal was presented to the cabinet and no objections were raised, why is Mahathir being singled out?

Notably, then Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Wan Azizah, Anwar’s wife, also did not oppose the move.

If cabinet responsibility applies, shouldn’t the entire cabinet be held accountable?

2. Political Motivation: Mahathir’s current status as a prominent opposition figure raises suspicions of political bias.

Is the focus on him an attempt to discredit an opponent, or is it driven by genuine national interest?

The hypothetical nature of the appeal’s outcome

Anwar and other critics have suggested that Malaysia could have regained Batu Puteh had the appeal proceeded.

However, such assertions remain speculative. Under international law, ICJ judgments are binding, and appeals are rare unless compelling new evidence emerges. The argument that Malaysia possessed such evidence has yet to be substantiated.

Mahathir’s decision to withdraw the appeal may have been politically unwise, but labeling it as “treachery” is arguably excessive.

The loss of Batu Puteh, while significant, was the result of a legal process Malaysia voluntarily agreed to.

Broader implications

The redaction of 27 pages from the RCI report raises concerns about transparency. What information is being withheld, and why? Critics argue that if national interest is at stake, full disclosure is necessary.

Additionally, the decision to focus the inquiry on Mahathir has drawn skepticism. Was this an attempt to appease certain political factions, particularly in Johor, which has a vested interest in Batu Puteh?

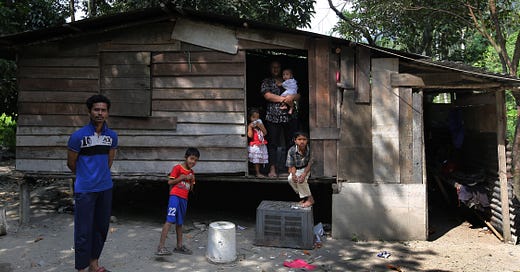

The historical context of Johorean fishermen using Batu Puteh during monsoon seasons underscores the emotional significance of the island.

Future diplomatic options

While the ICJ ruling has solidified Singapore’s sovereignty over Batu Puteh, this does not preclude future negotiations.

Diplomatic channels could potentially address unresolved issues or explore cooperative agreements over the area.

Conclusion: Accountability or political rivalry

The Batu Puteh RCI and its findings have reignited debate over Malaysia’s handling of the ICJ ruling.

While Mahathir’s withdrawal of the appeal may have been controversial, accusing him of treachery appears disproportionate. The focus should shift from political blame to a forward-looking approach that prioritizes national interest and diplomacy.

Prof. Dr. P Ramasamy

Malaysian, 75 years of age. Former professor of political economy UKM. Former Senior Research Fellow, ISEAS. Former Visiting Professor, University Kassel, Germany. Deputy Chief Minister Penang, 2008-2023. Former member of parliament, 2008-2013. Three terms Perai state assemblyman. Former Chairman of Penang Hindu Endowments Board. Involved in peace talks in Aceh and Sri Lanka.International peace consultant. Chairman of political party Urimai.

Subscribe Below:

The Batu Putih mess is the handiwork of a rather poor brief over which the Malaysian government spent several millions of dollars for little gain. The instructing advocates and solicitors representing Malaysia in the case were rather pallid in their arguments and certainly lacked depth to deal with a matter as complex as Batu Pitih was and remains.

Looking at the outcome of the Batu Putih matter through a 2024 lens is like trying to litigate the merits of a treaty between the British and the Sultanate of Johor narly 2 centuries ago whereby much of Malaysia's sovereignty was ceded over to a private family (the Johor Sultan) in breach of Malaysia's sovereignty and international law.

But then international law as we know it today was non existent during the time of British and other European colonial domination of much of the world. International law as we know it today is still (though more refined) set of colonial (Euopean) laws authored, edited and implemented through the use of forcce since world war 2. Those very set of rules, plundered and breached with impunity recognized more often than not in its breach than for its observance by the colonial powers is splitting at the seams today. Malaysia's legal team had no vision of the contemporary and prevailing position of intenrnational law and its fading impact on the multi lateral organizations that gave effect to its existence.

Malaysia's legal team in the Batu Putih matter, although consisting of a band of connected socalite lawyers, possessed no depth, dimension or intellectual integrity sufficient for Lauterpacht or anyone else of his calibre to deliver a compelling case for Malaysia before the court in any way that could have changed the outcomes for Malaysia.

Even in cases in which Sir Ian Brownlie (for Singapore) cannot be said to have ‘won’ his argument before the Court (as he saw it), he nevertheless often played an important role.

One could be forgiven for thinking that creative arguments advanced by the parties’ counsel, such as those often advanced by Sir Ian, can prove determinative in terms of how the Court ultimately arrives at its decision.

In reality, however, cases at the International Court of Justice are seldom ‘lost’ or ‘won’ in such a straightforward way. A party will often find some aspects of its submissions upheld by the Court while others are dismissed.

The fact of the matter is that even in those cases where a state does not obtain the satisfaction it seeks from the Court, the good arguments advanced by competent counsel in the written pleadings and oral arguments often give the Court food for thought and enrich the judges’ deliberations.

Through this process, Sir Ian Brownlie also contributed to the deepening of the International Court’s analytical understanding of a given case including Batu Putih without doubt.