Transnationalism is about the fluidity of borders and the way people, ideas, and cultures move across nations, connecting the world in ways that blur the traditional boundaries of the nation-state. It’s the opposite of being confined to one place, one identity, or one government. In today’s hyperconnected world, transnationalism explains how individuals and communities maintain ties across countries, integrating social, economic, and cultural practices that stretch beyond a single nation.

Jewish transnationalism is a prime example of this phenomenon. For centuries, Jewish communities have spread across the globe, from Europe to the Middle East to the Americas, yet they've maintained a cohesive identity tied to shared religious and historical experiences. Their network spans borders, with strong ties to Israel as a symbolic center, while each community adapts to its local context. But despite their far-reaching global connections, Jewish transnationalism doesn’t have deep historical links to the Malay Archipelago. While there may have been some indirect contact via trading routes, the Jewish story largely unfolded in other parts of the world.

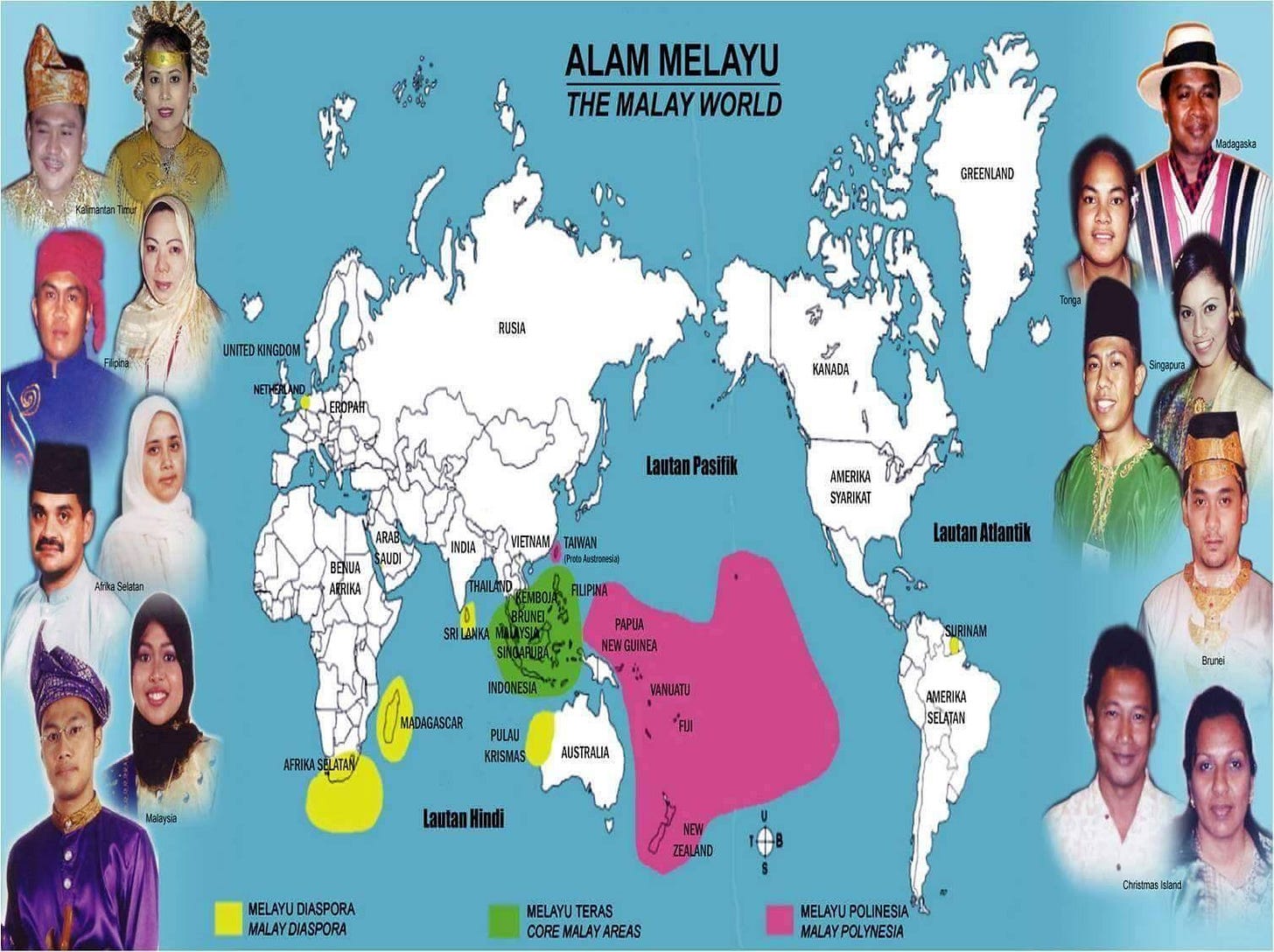

Meanwhile, we see transnationalism play out in another, less obvious way in the Malay world. The Malay diaspora—spanning from South Africa to Sri Lanka to Suriname—shows how Malays have migrated and spread, bringing with them their language, culture, and religion. In South Africa, Malays were brought as slaves or political exiles by the Dutch, while in Sri Lanka, colonial powers transported them as laborers. Despite being scattered across continents, these Malay communities have kept their cultural heritage alive, creating a web of connections that ties them back to their roots in the Malay Archipelago.

The question of whether the Philippines is part of this broader Malay world is an ongoing debate. In some ways, yes—southern parts of the Philippines, like Mindanao, share linguistic and cultural links with the rest of the Malay world, thanks to shared Austronesian roots. But politically and historically, the Philippines has often charted a different course, making it less firmly within the “Malay” category than nations like Malaysia, Indonesia, or Brunei.

This is transnationalism in action—whether it's the Jewish experience of maintaining a global identity or the Malay diaspora spreading across oceans. It’s the recognition that in our interconnected world, people, cultures, and ideas are constantly on the move, crossing borders and forming new, layered identities. Nations may have lines on a map, but the real story is how people are moving, connecting, and building lives across those lines.

Bangsa Serumpun

The concept of Bangsa Serumpun is like an invisible thread that ties together the Austronesian peoples across Southeast Asia, from Indonesia to Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines, and even beyond. It’s the idea that, despite modern borders, these nations share common roots—linguistically, culturally, and historically. At its core, serumpun means "of the same roots," and in the post-colonial era, this notion wasn’t just about culture; it carried real political weight. Leaders like Sukarno and Tunku Abdul Rahman understood that this shared heritage could be a powerful force, sometimes for cooperation, and sometimes for asserting dominance, as Indonesia did during the Konfrontasi period against the formation of Malaysia.

Sukarno, always thinking big, wanted more than just a unified Indonesia—he envisioned Palangkaraya, a new capital in the heart of Kalimantan, as the center of a broader Malay world that might include Malaysia and the Philippines. By relocating the capital to Borneo, Sukarno wasn’t just moving away from the colonial relics of Jakarta, but also signaling Indonesia’s ambition to be the gravitational force in the region. It’s interesting to see echoes of that idea today with the new Indonesian capital Nusantara, also in Kalimantan. While Nusantara may not explicitly claim the mantle of being the hub of the Malay world, its geographic centrality taps into Sukarno’s original vision of regional leadership.

Sukarno, the charismatic first president of Indonesia, was not just a revolutionary leader but also a Dutch-trained architect, having honed his skills at the prestigious Institut Teknologi Bandung. His intellect was matched by an extraordinary ability; he was said to possess a photographic memory, enabling him to recall vast amounts of information with ease. Sukarno was also the first to coin the term Marhaen, inspired by a destitute peasant he encountered in Java. This term eventually evolved into Marhaenism, a socio-political philosophy that emphasized the importance of the working class and the peasantry in Indonesia's struggle for independence.

Beyond his architectural and political pursuits, Sukarno was actively engaged in international diplomacy. Sukarno’s deep appreciation for Al Azhar University stemmed from his recognition of its role in shaping Islamic scholarship and thought, especially for Muslims from regions like the Malay Archipelago. When Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser sought to reorganize the institution under Law 103 of 1961, bringing it under state control and making the appointment of the grand sheikh the president's prerogative, Sukarno petitioned against these changes. He understood that Al Azhar was more than just a religious institution; it was a hub for intellectual and cultural unity among Muslims globally.

Sukarno reportedly remarked that people from the Malay Archipelago traveled to Egypt not to visit the Pyramids, but to study at Al Azhar. This highlights the symbolic significance Al Azhar held for the broader Islamic world, including Southeast Asia. His multifaceted contributions—from architecture to political philosophy and cultural diplomacy—paint a portrait of a leader deeply engaged with both national identity and global affairs.

On the other side of the South China Sea, José Rizal had his own vision of identity. The Filipino revolutionary didn’t just see himself as Filipino; he saw himself as part of the broader Malay race, recognizing the shared roots of the peoples in the archipelago. For Rizal, this idea wasn’t just cultural—it was political. It provided a unifying identity that transcended colonial lines, as Filipinos, Malaysians, and Indonesians were all part of the same broader family. It’s fascinating to note that at one point, there was talk that the Philippines might even adopt the name Malaysia, emphasizing this Malay connection. But ultimately, Tunku Abdul Rahman claimed the name for his own newly formed federation in 1963, cementing Malaysia’s place in the regional narrative.

Today, Bangsa Serumpun still holds sway, not just as a cultural concept but as a way to foster regional solidarity. It’s a reminder that despite the colonial borders that once divided the region, there’s a shared identity that stretches across the islands and seas. Whether it’s through ASEAN cooperation or informal diplomatic ties, this idea of a shared Malay heritage helps shape the way nations in Southeast Asia interact with one another, pulling them together in a world that is constantly being pulled apart by nationalism and geopolitics.

Samirul Ariff Othman

Born in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Samirul Ariff was bathed in the Zam Zam Water and circumambulated around the Kaaba. His early education spanned the Asia-Pacific region. He attended pre-school in Thailand and elementary school at St. Mary’s International School in Tokyo before continuing his studies at MARA Junior Science College (MRSM) in Malaysia. Despite his global upbringing, Samirul remains deeply connected to his Malay Muslim heritage.

Subscribe Below:

The Malays in the wider sections of the diaspora never migrated (voluntarily at least). They were transported ass slaves by the Portuguese, the British and the Dutch as were Indians found in the far reaches of the wolrld..

The Jews on the other hand are a cult. There was no land of Isael from which they were dispersed by the Roman as the myth goes. Yisroel means in Aramic "In whom God is plased". From this statement came various interpretations including "Israelis", the "Chosen" who God promised to redeem and give a home called Israel. A variation to the word Yisrol. If you believe that, which I am afraid many people do, then you believe in the tooth fairy, Santa Clause (who by the way was a Turk) and the gnome at the bottom of the garden.

The Malays of course are an intelligent people who are in fact sspread over a wide area of South East Asia and beyond (India's North Eatern States). But the world having been carved out by Europeans and Mongols over several millienium means that many of the Malays living in places like Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Myanmar and North Western India are wrongly identified as being racially and culturally different to the Malay.