How East M'sia can lead in political transformation

Carolyn Khor, Murray Hunter & Lim Teck Ghee

Among the advantages of an East Malaysian-led or influenced government is its potential to reject pressure from racial and religious extremism.

Unlike the peninsula, Sabah and Sarawak have historically been more tolerant and diverse in their religious and secular practices.

By promoting inclusivity and pluralism, an East Malaysian bloc can mitigate the influence of extremist ideologies in politics and the civil service.

Another is the much more multiracial and polyglot communities in the two states and the absence of the traumatic May 13 racial chapter of history which transformed peninsula politics and society.

Its dark shadow is also repeatedly raised by peninsula politicians stifling the nation’s progress from becoming a psychologically and mentally liberated society.

To address the challenge of political transformation effectively, we have compiled a list of issues and assessed how East Malaysian parties and leadership can provide much-needed change to the current political landscape.

From social cohesion to economic development, environmental sustainability to indigenous rights, there are numerous areas where East Malaysia can lead the way in driving positive change.

The success of political transformation in Malaysia also hinges on the active participation of all stakeholders from East and West, especially the younger generation, including think tanks, professional elites, NGOs, media, and businesses big and small.

ADS

Only through collective action and collaboration can we overcome the barriers to change and build a progressive, more inclusive, and equitable society.

Collaboration among stakeholders from wherever they are - and not just from Putrajaya and the capital cities - is key for leveraging local and regional interests and driving national change.

Here’s a possible framework for how parties in East Malaysia could collaborate to form a cohesive bloc:

1. Identifying common goals and priorities

Parties in East Malaysia should convene to arrive at shared objectives and priorities that resonate with the people’s interests and aspirations.

Common goals could include identifying and effectively addressing the root causes of racial and religious tensions; strengthening the everyday ways to fight against racism and injustice; and taking action against growing systemic racism by reforming structures, policies, and practices that contribute to the wealth gap, socio-economic disparities, and to inequalities in educational access, outcomes, and beyond.

This includes the clamping down on extremism such as what we are witnessing today with “Sock-gate” which threatens not just the spirit of multiracialism but also the livelihoods of innocent employees and their families.

If unresolved, it constitutes a danger to the retention and influx of local and foreign businesses and investment and may trigger an emergency.

Once this balance has been restored, only then can we progress, as other countries in the region have, without the distractions from extremists and polarising forces intent on imposing their narrowly constricted racial and religious values onto the rest of the country.

2. Continuous dialogue

Any ongoing dialogue and collaboration should be strengthened and expanded, allowing participating parties to engage other parties and stakeholders to discuss strategies, coordinate actions, and address differences constructively.

The recent merger between the Progressive Democratic Party (PDP) and Parti Sarawak Bersatu (PSB) is one good example.

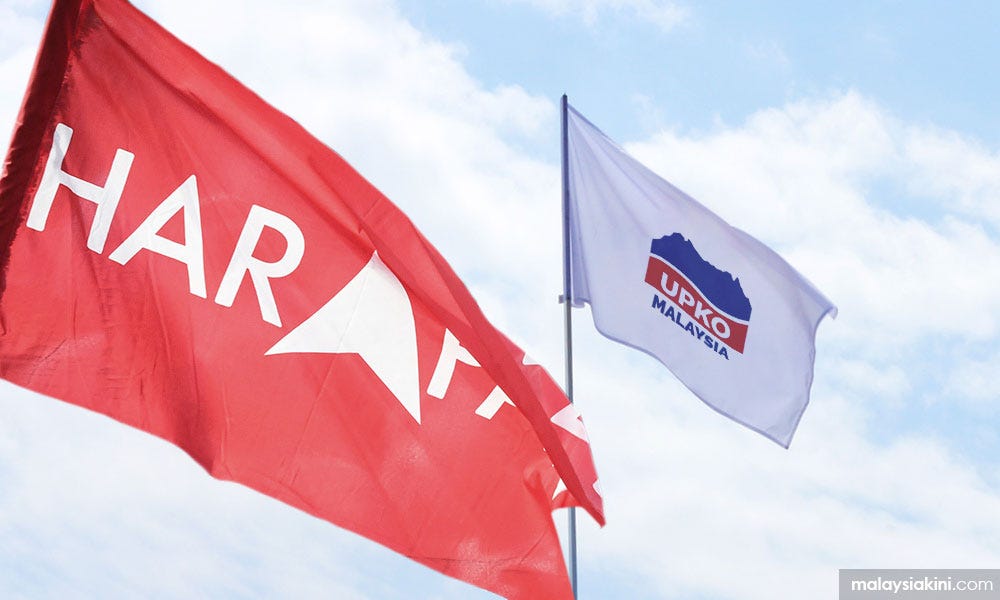

The United Progressive Kinabalu Organisation (Upko)’s current good relationship with the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and Pakatan Harapan are positive indicators for a more inclusive and forceful voice from Borneo at the federal level.

These parties must also prioritise building trust and solidarity among themselves, recognising the diversity of perspectives and interests within the bloc to foster a strong sense of unity and purpose. And they can and must reach out to the smaller peninsula parties.

Collaboration should extend beyond political parties to civil society organisations, community leaders, and grassroots movements. By engaging with diverse stakeholders, the bloc can strengthen its legitimacy, broaden its support base, and ensure its agenda reflects the needs of the people.

As a united bloc, parties in East Malaysia can then leverage their collective influence to advocate for policy reforms and legislative initiatives that advance the region’s and national interests. The bloc can also amplify its voice and effectively negotiate with other political stakeholders.

4. Coordinating electoral strategies

Needless to say, political parties exploring opportunities for strategic collaboration to maximise their collective impact should start discussions as early as possible to avoid potential problems and start groundwork early on a common platform.

If candidate selection can be agreed upon sooner than later, voters will be more inclined to decide on the right candidate on election day.

5. Commitment to save Malaysia

The bloc can withstand any challenges or opposition from detractors by creating a strong force through cementing relationships and institutionalising cooperation. This includes collectively winning as many seats as possible to empower the bloc to effect positive changes in Parliament.

The window of opportunity is now evident, considering the fragmented government formed after the 15th general election. The East Malaysian grouping can take heart that their current 25 percent share of the 222 parliamentary seats will increase substantially after the next redelineation exercise.

But it is not only numbers that count. Is there the quality, pragmatism, and most importantly, idealism in the East Malaysian leadership that can make the difference in policy making and implementation that comes after the next GE? We have seen Harapan falter, and many now conclude, fail in reformasi.

East Malaysian parties now possess the advantage of being courted in national issues and policies due to the evolving and fluid political environment.

With the current power dynamics, contrasting ideologies, and competing interests, East Malaysian parties and politicians now hold the opportunity to drive bold messages and actions of reform and unity which can contribute to a better - and not the same - Malaysia.

Immediate action can begin with East Malaysian activists and political parties taking the lead in organising parades, marches, and similar events to bring home to Malaysians the diversity and unity they are committed to protecting and nurturing.

See these videos as examples:

The leaders in Sabah and Sarawak may not be perfect, but there are no other options since the Semenanjung (peninsula) leaders appear to have their hands tied and mouths gagged.

Indeed, an East Malaysian bloc offers a unique opportunity to break the peninsula-centric and Malay bureaucracy-dominant mould that has long defined and continues to hold back Malaysian politics and national progress.

Last but not least, collaboration among parties in East Malaysia with the West presents a promising avenue for contributing to a broader transformation that brings the nation back to our original secular roots and identity.

This is Part 3 of a three-part series.

Part 1: The East Wind could be GE16 game-changer

Part 2: Policy transformation: Truly M'sian leadership needed

LIM TECK GHEE is a former senior official with the United Nations and World Bank.

MURRAY HUNTER is an independent researcher and former professor at the Prince of Songkla University and Universiti Perlis.

CAROLYN KHOR is a former ministerial press secretary, a former United Nations Volunteer and an independent researcher/writer.

Originally published in Malaysiakini 10th April 2024

Subscribe Below:

The first thing that comes to mind when it is about relationships between "West Malaysia" and "East Malaysia" is that there's none in reality. Other than going through the motion of "government", there isn't really anything else going on. When you can get Sarawakians and Sabahans to give you anything other than a "courteous" answer you will find out they are hardly fans of anything "West Malaysian", basically, they loath "the Peninsular". No wan can or should blame them.

Sarawakians and Sabahans find "West Malaysians" arrogant, unbearable, tedious, and full of themselves. In other words: full of the brown stuff. "West Malaysians" like to think of themselves as more "civilised" while actually being more backward in manners, charm, and sophistication.

When the monkeys from "West Malaysia" (WM) come to "East Malaysia" (EM) to find out if the natives "live on trees", discover they don't so that the monkeys from WM cannot feel superior. Better than that, EMsians, with the rare exceptions of those corrupted by the vulgar monkeys of WM, are not much tainted by racist and religious bigotry that are found as the only things alive and thriving in WM.

The Chinese, Malays, and all the others get along mighty fine with each other and even with dogs. When I used to go over to hunt (oinks), the hunting dogs are mostly supplied by the Malays (who ferried them around as rear passengers on their motorbikes). It's not unusual for Malays to have dogs, an imam friend keeps dogs, a Chinese friend who lives in a Malay kampong is often thanked for his dogs being the guardians of the kampong, keep robbers away.

I know EMsians would take issue with the article which is the presumption that, the author uncles and aunt, I suspect, are outsiders who's appointed themselves to teach EMsians what to do. Since, presumably, the poor EMsians have yet to learn how to think. I would suggest their esteemed teachers take their wisdom and just fcuk off. It is rather condescending even to tell EMsians they are better endowed to teach WMsians how even to run "Malaysia".

EMsians have never been enthusiastic about the neo-colonial creation, given half the chance, they'd sooner cut their losses and fcuk off from "Malaysia". If any WMsian has close friends in EMsia, they would intimate to him they would prefer not to be honoured with being any part of "Malaysia". During their marches for their alternative independence day and their Sarawak for Sarawakians demos you'd find huge numbers of folks who want out. And that includes many of Sarawak's Malays, who are not exactly fond of their WMsian "big brothers". Btw, I doubt any genetic tests would show the EMsian Malays have much genetic similarity with the WMsian Malays, it is worth a good look into.

Since the general idea is to be out of the picture altogether, it might be a better idea to perhaps encourage EMsians not to be any more in the privileged position to become more and more like WMsians, just leave WMsia and let the "big brothers" rot in their racist and religious bigotry, and their gross inability to be effectual in anything.

East malaysia can lead in political transformation by having a bigger population.

At the moment, east malaysian represent only 16% of the population but are overrepresented in the parliament of up to 25%. This is not enough.

West malaysian represents 84% of the population and are represented by 75% of the voice in parliament.

Major ethnic group are malays of about 70%, chinese 22% and the rest 8%.

Since most vote via racial lines, east malaysians need to increase their race to a higher portion, only then can they lead in political transformation.