Malaysia: Activist investigated for sedition, protesters harassed and increasing online controls

Published on CIVICUS 12th August 2024

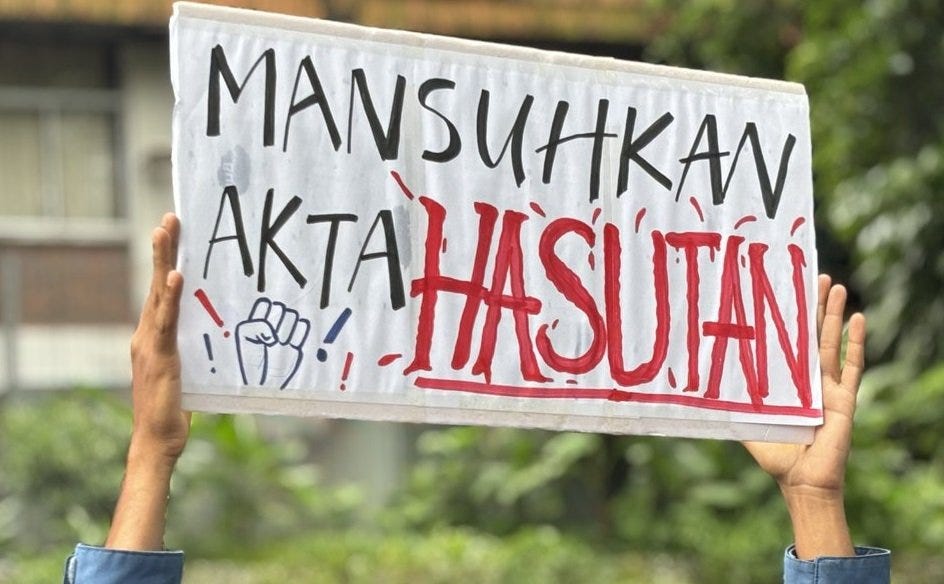

Protest against the Sedition Act outside the Malaysian parliament, July 2024 (Photo Credit: @partisosialis)

Published on CIVICUS 12th August 2024

Malaysia’s civic space is rated as ‘obstructed’ by the CIVICUS Monitor. Among ongoing concerns are the array of restrictive laws, especially the Communication and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA) and the Sedition Act, that have been used to silence online dissent and to harass human rights defenders. Critical news websites and blogs have been blocked. Peaceful protesters continue to be hauled in by the police for questioning under the Peaceful Assembly Act. Malaysia has also yet to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

In June 2024, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk visited Malaysia. In his end of mission statement, he called for the review of the colonial-era Sedition Act, as well as other vague and overly-broad legislation like the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act (Sosma). Türk also highlighted how laws such as the CMA, the Peaceful Assembly Act and Printing Presses and Publications Act continue to be used against human rights defenders, including environmental human rights defenders.

Malaysia’s Universal Periodic Review (UPR) was adopted on 5th July 2024, at the UN Human Rights Council. Civil society groups including CIVICUS, SUARAM, FORUM-ASIA, ARTICLE 19 and CIJ highlighted how the government had backtracked on previous commitments to ratify the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The government also did not accept any recommendations by UN member states to repeal laws that curtail freedom of expression, such as the Sedition Act, Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act, and the Printing Presses and Publications Act as well as recommendations to revise the Peaceful Assembly Act, which has been used to restrict and criminalise protests.

A ‘Repressive Laws Monitoring Report’ by FORUM-ASIA identified online defamation as a major concern, particularly citing the Printing Press and Publications Act 1984 and the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998. These laws are frequently employed to restrict freedom of expression, silence dissenting voices and punish those exposing corruption and misconduct.

In recent months, human rights defender Mukmin Nantang was arrested for sedition while political activists were also criminalised under the draconian law. The authorities filed a police report against a blogger and questioned journalists over media reports around a casino and a planned police leadership reshuffle. Malaysia’s press freedom ranking dropped drastically while licensing introduced for social media platforms has raised free speech concerns. The government intimidated organisers of a human rights film festival, arrested protesters in Sabah and attempted to block an anti-government protest. The police also used heavy-handed tactics to block a protest demanding accountability. An opposition party was denied registration.

Expression

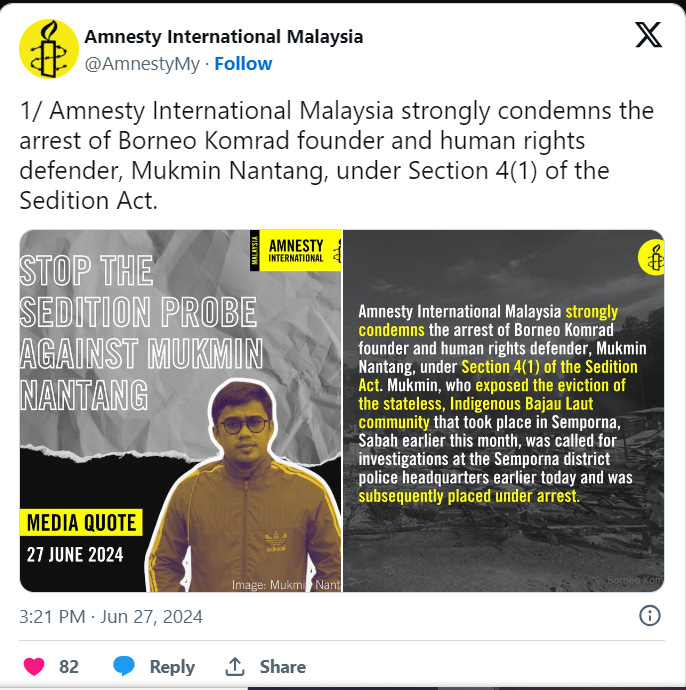

Sedition investigation against human rights defender Mukmin Nantang

Human rights defender Mukmin Nantang was summoned to the Semporna district police headquarters on 27th June 2024 for speaking up on the rights of an indigenous community. The police informed him that he was arrested under Section 4(1) of the draconian Sedition Act. He was released on bail shortly after his statement was recorded.

The Sedition Act 1948 provides for a fine of up to RM5,000 (USD 1,126) or imprisonment for up to three years, or both, upon conviction. The colonial-era law has routinely been abused by authorities to suppress dissent, silence opponents and criminalise critical comments against the royalty.

Mukmin Nantang is one of the founders of Borneo Komrad, a youth-led organisation based in the state of Sabah that focuses on education for stateless children. According to ARTICLE 19, the arrest and investigation are reported to relate to his peaceful advocacy for the rights of the Bajau Laut people, an indigenous community in Sabah that faces systematic forced eviction, injustice and barriers to obtaining official identification documents, rendering many members of the community stateless.

The Bajau Laut people have been forcibly evicted from their ancestral lands due to coastal development projects and environmental conservation policies that fail to consider their rights and needs. The most recent incidents of the Bajau Laut people’s displacement were a series of evictions that took place from 4th to 5th June on seven islands in Semporna, including Pulau Bohey Dulang, Pulau Maiga, Pulau Bodgaya, Pulau Sebangkat, and Pulau Sibuan.

Criminalisation of political activists

Political activists have also been targeted for their comments critical of the government or royalty.

On 29th April 2024, political activist Badrul Hisham Shaharin, otherwise known as Chegubard, was charged under Section 4(1)(c) of the Sedition Act. These charges stemmed from his Facebook post citing a Bloomberg report that claimed Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim had met with business leaders over a casino licence in Forest City, which the Prime Minister has denied.

Badrul is also facing two counts of making seditious remarks and defaming the King for questioning his meeting with the owner of KK Mart. He is facing charges under Section 500 of the Penal Code which provides for a maximum jail term of two years or a fine, or both, upon conviction. He has also been charged under Section 4(1)(c) of the Sedition Act 1948.

On 30th April 2024, police arrested blogger Wan Muhammad Azri Wan Deris, more popularly known as Papagomo, for alleged seditious remarks made against the King in a Twitter post. He is also facing trial under Section 4(1) of the Sedition Act 1948 for accusing the government of being pro-Israel and pro-West.

Internet regulator files police report against blogger

On 29th April 2024, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) filed a police report against blogger Murray Hunter over his claim that the internet regulator was “a politicised institution” and had “acted in excess of its jurisdiction”. It also said Hunter’s comments seemed to be defamatory.

MCMC said Hunter’s article went against Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act, which deals with offences linked to the use of network facilities to transmit communication deemed to be offensive or which could cause annoyance to another person. It said Hunter should have filed a complaint through official channels if he had issues with MCMC.

In response, rights group Lawyers for Liberty (LFL) criticised MCMC for their actions, saying that it was “heavy handed and unnecessary”. It also said a public body funded by taxpayers “had no business complaining of defamation”. LFL added that the MCMC must accept public criticism, even if it is harsh, and that if any criticism is unfounded it is open to them to respond and clarify and not to file criminal complaints against legitimate criticism.

Journalists questioned by police over media reports

In May 2024, a Bloomberg journalist was hauled in for questioning over a report about purported plans to build a casino. The journalist, Ram Anand, was one of three journalists who contributed to the Bloomberg report.

Police said investigations are being carried out under Section 4(1) of the Sedition Act, Section 500 of the Penal Code, and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998.

The Bloomberg report, citing anonymous sources and published on 25th April 2024, said that Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim met top Berjaya Corporation and Genting Group executives to discuss the potential for a casino complex at the Forest City project in southern Johor state, in Forest City, Johor, a troubled real estate development. The report said representatives of Malaysia’s king, Sultan Ibrahim Iskandar were also present.

On 26th April 2024, Anwar referred to Bloomberg’s report as a “lie” and said those mentioned in the report “must take the necessary action”. He called on local private companies to take action against Bloomberg news agency.

Shawn Crispin, CPJ’s senior Southeast Asia representative said: “Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and the companies mentioned in Bloomberg’s casino report should walk back their threats to the anonymous sources cited in the story and allow the news agency to report on issues of national import without fear of reprisal.”

In another case, police summoned three Malaysiakini journalists on 9th August 2024 over a news report on a possible reshuffle at the Bukit Aman police headquarters, However, the reporters - B. Nantha Kumar, Hariz Mohd and Shahrin Aizat Noorshahrizam - stood firm in not revealing the source’s identity.

The Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) urged the government to stop harassing the media in its bid to compel the disclosure of sources. It said protection of sources is an internationally recognised principle, and invoking “archaic and repressive local laws” to force the media to reveal sources is likely to prevent whistleblowing and lead journalists to self-censor. It is also likely to be seen as a form of harassment and intimidation against the media.

Malaysia drops 34 places in global press freedom index

In May 2024, Malaysia’s standing in the World Press Freedom Index declined by 34 places to 107th compared to 73rd in 2023. The World Press Freedom Index 2024 report released by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) showed that Malaysia’s score now stands at 52.07 points.

RSF noted that “the government exerts a great deal of political pressure to deter the media from tackling sensitive subjects or from criticising politicians and government officials. The authorities are after investigative reporters, and the monarchy is an extremely sensitive subject, as are discussions on race and religion. Any form of commentary or reporting deemed critical of the monarchy can result in prosecution, leading to widespread self-censorship on the matter.”

RSF raised concerns about the existence of draconian legislation and that the Printing Presses and Publication Act gives the government strict control over the licensing of print media outlets, while the Communications and Multimedia Act is often used to curb what the authorities consider "fake news".

Following this, the Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) criticised the government for minimal progress in reforming laws that restrict media freedom, despite election promises. Director Wathshlah Naidu highlighted ongoing suppression of journalists and persistent online censorship, hindering unbiased reporting and discussions on sensitive topics. Naidu added that while certain laws like the Printing Presses and Publications Act (PPPA) and Sedition Act were not directly enforced against media, they fostered self-censorship due to legal fears. CIJ urged the government to amend or repeal these laws and sections of the Penal Code to safeguard media freedom and public interest discourse.

Licensing for social media platforms raises concerns

At the end of July 2024, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) announced that social media and online messaging platforms with at least eight million registered users in the country must apply for a licence, effective 1st January 2025.

The MCMC said the new regulatory framework would help to combat the rise in cybercrime offences, including scams and online fraud, cyber bullying, and sexual crimes against children.

This move has sparked concerns. On 27th July 2024, civil society organisations wrote an open letter to the Prime Minister to express their concerns. The letter highlighted that the government has had a track record of using its punitive powers to silence criticism and dissent and that this latest move by the administration is a blatant abuse of power and poor governance and an attack on a healthy, functioning democracy. The letter also stated that the current administration has expanded censorship and curtailed criticism and healthy discourse based on arbitrary definitions of ‘sensitive content’ that are not rooted in international human rights standards and practices.

The groups called for the establishment of a multistakeholder mechanism for the oversight of content moderation on social media – a Social Media Council (SMC) – as an inclusive self-regulatory framework; investment in media and digital literacy programmes and to institutionalise consultative processes with civil society experts and the public.

Film festival faces intimidation from Home Ministry

On 5th August 2024, activists spoke out against the Home Ministry for what they deem to be “intimidation” against the organisers of the Freedom Film Fest., a yearly human rights film festival at Petaling Jaya Live Arts Centre.

Enforcement officers from the Home Ministry visited the venue of the festival for two days in a row to inspect the event and check that the films screened did not breach the Film Censorship Act. Although the show continued, activists said such visits were “archaic” and a form of “intimidation” against free speech and expression.

Firdaus Husni from the Malaysian Centre of Constitutionalism and Human Rights said: “If the Madani government is serious about reforms, why are we still resorting to tired intimidation tactics like this?”

Peaceful Assembly

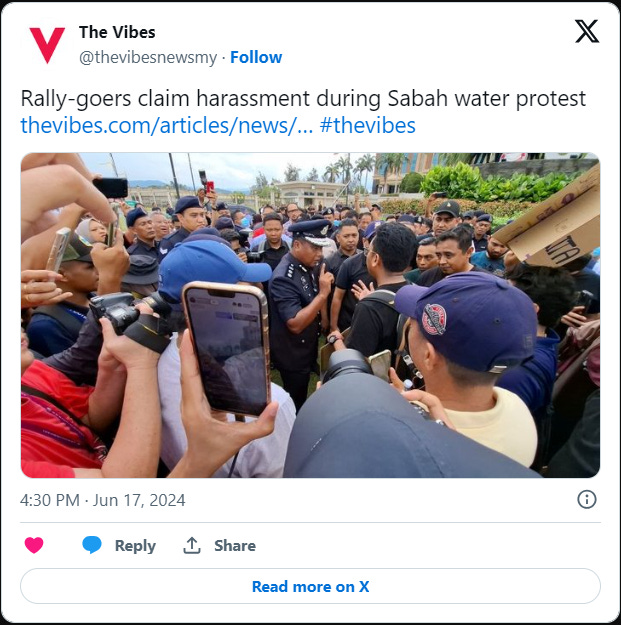

Police arrest protesters seeking improved water access

On 14th June 2024, groups including students and NGOs held a peaceful demonstration, dubbed #KamiMahuAir (#WeWantWater) outside the Chief Minister’s office in Kota Kinabalu, calling for improved water access for students at the University of Malaysia Sabah.

According to Amnesty International Malaysia, following the protest, eight students - at least three of whom are children - and their teacher were then held on remand in detention.

The students, who are from the Bajau Laut indigenous community, attend an alternative school for stateless students, and were held under the Immigration Act 1959/63. Their teacher, a Malaysian citizen, was released after two days in detention. The students were held in police lock-up for seven days before being released.

Katrina Jorene Maliamauv, Executive Director of Amnesty International Malaysia said: “These students, including children, were victims of blatant discrimination due to their identities as stateless persons and members of an ethnic minority. Though we are relieved they are now free, it is alarming they were arrested in the first place.”

Protesters face harassment from police over anti-government rally

A protest dubbed the ‘People against Anwar’ (Rakyat Lawan Anwar) was called by the Demi Negara movement on 29th June 2024, in front of the Prime Minister’s official residence, Seri Perdana, in Putrajaya.

Ahead of the protest, the organisers notified the police as required by law. Despite this, the police declared the protest illegal and attempted to block it using the justification that the organisers had not obtained permission from the owner of the proposed venue, Putrajaya Corporation, to hold the event, despite it being a public location. The police also advised the public not to participate in the rally and said strict action would be taken.

Police also said that they had received 85 reports on the planned rally and had opened an investigation paper under Section 505 (b) of the Penal Code and Section 233 of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998.

Police also summoned three social media influencers linked to the Demi Negara movement including YB Viral, Tunku Intan Abdul Hamid (Dayangku Intan), and Siti Zulaikha Olivia (Mak Iban Olivia).

Despite this, the protest went ahead and about 250 protesters gathered. The protesters were clad in black attire, with some wearing the watermelon symbol clothing, or keffiyeh, to show solidarity with Palestinians. The group made eight demands, including to address the rising cost of living, protect public healthcare staff, ensure fair wages, uphold freedom of speech and maintain economic sovereignty.

Following the protest, police launched an investigation under Section 9(5) of the Peaceful Assembly Act. Twelve individuals, including the organisers, were identified to provide statements.

Heavy-handed tactics to stop peaceful assembly seeking accountability

Police used heavy-handed tactics to block a protest walk organised to highlight the lack of accountability surrounding the death of Teoh Beng Hock 15 years ago at the Selangor Malaysia Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) headquarters.

On 13th July 2024, the Teoh Beng Hock Association for Democratic Advancement (TBH-ADA) organised a “Walk for Justice” from Plaza Masalam in Shah Alam to Parliament.

According to ARTICLE 19, on 15th July 2024, during the final leg of the walk, as the group approached the Parliament gates to submit a memorandum to the Prime Minister, they were intercepted by a barrier of police personnel that had formed approximately 100m from the entrance. Despite the peaceful nature of their demonstration, the police refused to allow the submission of their memorandum in front of Parliament. Instead, the police pursued the activists, causing Teoh Lee Lan, the sister of Teoh Beng Hock, to fall during the altercation. One woman – a member of the demonstration’s organising committee – was grabbed at the collar by a policeman, which broke her necklace and left red marks on her neck.

Shortly after the altercation, the group were allowed to deliver the memorandum at the Parliament gate together with some Members of Parliament.

Following the protest, police summoned three individuals to give their statements under the Peaceful Assembly Act 2012 on 17th July 2024. However, this was cancelled at the last minute which enraged the organisers.

Teoh Beng Hock was found dead on 16th July 2009 after being questioned overnight at the Selangor MACC headquarters. He was then the political aide to Selangor executive councillor Ean Yong Hian Wah. A Royal Commission of Inquiry in 2011 determined that he was driven to commit suicide following aggressive questioning by MACC officers. However, a 2014 Court of Appeal ruling contradicted this, attributing his death to multiple injuries caused by unknown persons, including some MACC officers.

Association

Authorities reject application to form political party

In July 2024, the Registrar of Societies rejected Indian-based party Urimai’s application for registration. P Ramasamy, chairman of Urimai’s interim leadership committee, said that after eight months they were informed of the rejection on 4th July.

Ramasamy said that the decision was not surprising, blaming it on what he said was a vendetta by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s government against his party for not supporting the Pakatan Harapan-led coalition government.

P. Ramasamy, chairman of Urimai’s interim leadership committee, said the party’s legal team is working on an appeal to home minister Saifuddin Nasution Ismail within the 30-day stipulated period.

CIVICUS has documented how the Societies Act 1966 remains unduly restrictive and heavily burdensome. Organisations that have attempted to register with the Registrar of Societies (ROS) have experienced excessive waiting periods as there is no fixed time period to decide upon a registration application. Potential grounds for refusal by the ROS are drafted in vague and overly broad language. In recent years, the Act has been used to delay or reject the formation of political parties, especially those in opposition.

The application of Malaysia United Democratic Alliance, MUDA, a youth-led party, that was submitted in September 2020, was rejected twice. Its application was finally approved in December 2021 following a successful legal challenge against the Home Minister. The application of political party Parti Pejuang Tanah Air (Pejuang) in August 2020 was rejected by the ROS in January 2021 but finally approved in July 2021 after a legal challenge at the High Court.

Subscribe Below:

Good. Now for the cane and deteention under a new ISA. A more stringent and draconian one at that. Who gave the media, especially the social media types, a mandate to run the country or interfere and disrupt government (apart from Regime Change and the NED)?

We've got Weatsheaf here in a blue zooper car. Lochinver.