The evolution and influence of thinking in management Part 6: Leadership

An unpublished series of management ideas

The sixth part covers ideas and practices which have shaped the way we think about leadership today.

Leadership Thought

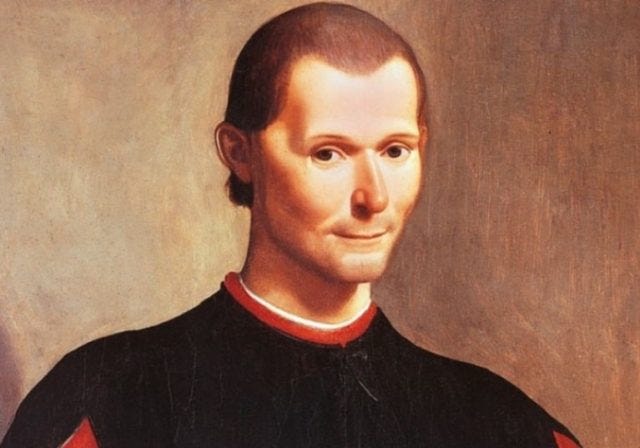

Niccolo Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy in 1469. Machiavelli entered the Florentine government as a secretary and quickly rose and was soon on the council responsible for diplomatic missions. Machiavelli was later dismissed from office when a political change took place. He was never able to return to office because of the controversy of his books had on his character, many believing he was ruthless and uncompassionate.

Machiavelli’s writings showed insight about how a leader could develop and stabilize a government, particularly about the human character of leadership. Machiavelli’s views completely lacked sentimentality, were amoral (i.e., he left out judgments about religious ethics and wrote more from the point of view of a paganistic nature) and took a pragmatic and effective view of things. He did not make his views known about right and wrong[i].

Machiavelli’s best known book is The Prince which describes the methods by which a leader can gain control of the realm. Machiavelli focuses on the conquering prince who has a difficult task of stabilizing his new found power and realm and needs to build a structure and organization that can be sustained. A prince publicly must be beyond reproach, but behind the scenes things are required of him that are of an evil nature in order to achieve the greater good.

Niccolo Machiavelli

Machiavelli’s second work his Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy is a set of works on how to start, develop and maintain the republic. Each book begins with a principal which is supported with Livy’s history of Rome and other ancient models of history. Many of the concepts in this work such as checks and balances and the strength of the tripartite government structure are still valid today and similarities can be seen in the structure of many democratic governments today.

Machiavelli had profound insights into organization and it’s dynamics centuries before modern management thinkers wrote about them. He talked about setting goals and objectives and developing accountable bureaucracies. Machiavelli also talked about using shared values to develop a shared commitment and common purpose in the organisation[ii], something features very prominently in the contemporary ideas of organizational culture and leadership models. Machiavelli saw the restrictiveness of the organization upon the individual[iii], prominent in the concept of empowerment today and that shareholders are really not the group that ultimately controls the organisation[iv].

Machiavelli was misunderstood in his own time and continues to be. Today a person who is deemed to have a Machiavellian personality is seen as manipulative and unethical in their behaviour and attitudes[v]. The concept of ‘the end justifies the means’ goes back to Machiavellian thought, where evil actions can be justified because it will ultimately create good for the greatest number of people. However this could be a grave misinterpretation of Machiavelli, further evoked in modern times through the popular cottage industry of books published about Machiavellian ideas. In The Prince, Machiavelli placed a number of restrictions on evil actions, stating, 1. this was only acceptable for the stabilization of the state, 2 individual power for powers sake is not acceptable and does not justify evil actions, and 3 it should not arise out of selfishness and degeneracy[vi]. Perhaps Machiavelli is only being criticized for his blunt and honest appraisal of basic human nature, stripped of it’s moral overtones. In modern management we can see many examples of this, such as the example of the cutting of staff in the name of empowerment or lean production, where management really has another agenda, mentioned previously in this section.

Machiavelli’s works have the status of classics and have tremendous political, organizational, strategic and political genius. This can be seen if one understands that Machiavelli’s intention was to eliminate cultural and religious values to provide a naked view of human instincts. Machiavelli’s contribution was the beginning of political science and understanding the nature of power. Machiavelli’s premise was that power is neutral and good or evil is generated by the way it is used. Organisations, firms and corporations can also be seen through a political paradigm, as a way to understand it’s dynamics from the power pint of view. Anthony Jay brought Machiavelli into management prominence and thought in his 1970 book Management and Machiavelli.

Psychologists understood the importance of leadership on conflict, cohesiveness, motivation, power and the overall effectiveness of the organisation. Leadership was recognised as the difference between success and failure, whether in business, government, politics or sports games. Yet with its importance, up until the 1930’s the qualities of successful leadership were still an unexplainable concept. The pioneers of leadership studies were Ronald Lippitt and Ralph White.

Lippitt and White undertook a study of three boys clubs, each subjected to different types of leadership, authoritarian, democratic and laissez faire. The authoritarian leader was very directive and allowed no participation, the democratic leader encouraged group discussion and decision and the laissez faire leader gave complete freedom to the group. Under control conditions the leadership styles were practiced to see their effects on satisfaction, frustration and aggression. The boys found an overriding preference for the democratic leader. Boys subjected to the authoritarian leader either behaved aggressively or apathetically. The laissez faire style actually produced more aggression than the autocratic style[vii].

Sweeping generalisations could not be made from the studies as the effects on productivity were not measured. However this study had great historical significance in a similar manner to the Hawthorne studies and proved in a scientific way that different styles of leadership can produce different reactions from the same groups.

Rensis Likert in the mid 1940’s undertook a study of supervision, productivity and satisfaction that group members derive from participation at the Michigan offices of the Prudential Insurance Company. Results showed that supervisors of high productivity sections were more likely to;

· Receive general, rather than close supervision from their supervisors,

· Like the amount of authority and responsibility they have in their jobs,

· Spend more time in supervision,

· Give general rather than close supervision to their employees, and

· Be employees orientated, rather than production orientated[viii].

The low productivity supervisors had essentially the opposite characteristics. The employees orientated supervisor became the general model of supervision for the human relations school of thought. This research has been often cited as proof human relations type of approach is effective in management.

Rensis Likert

In 1945 the Bureau of Business Research at Ohio State University initiated a series of leadership studies. The studies started with a premise that no satisfactory definition of leadership existed. The outcome of the study showed that leaders high on initiating structure (goals and tasks) and consideration (friendly, trusting, respectful and warm) have employees who show high performance, low turnover and low grievances rates. Leaders low on initiating structure and consideration have subordinates with low performance, high turnover and high grievance rates. Leaders who display a combination of high initiating structure, but low consideration resulted in high performance, but also high in turnover and grievance. Leaders with a combination of low initiating structure and high consideration resulted in low subordinate performance as well as low turnover and grievance rates[ix].

These studies were the first to show the importance of task direction and consideration of individual needs in leadership behaviour and highlighted some of the faults in scientific management, still the benchmark in supervisory theory at the time.

Robert Blake and Jane Mouton developed a very popular at the time grid of various managerial styles in the mid 1960’s. The grid shows on one axis concern for people and on the other axis concern for task accomplishment. These were similar variables to both the Ohio and Michigan studies. The grid identifies five basic styles of management representing various combinations of task orientation and concern for people. Blake and Mouton point out the the best style will depend upon the situation[x], i.e., factory, country club, school, office, etc. This approach was to become important in organisational development where practitioners wanted to shift employees’ values within the organisation.

Research to date had still failed to provide an overall theory of leadership, so Fred Fiedler turned his attention on the situational aspects of leadership. During the 1940’s he searched for the situational variables that impact on leadership roles, skills and behaviour, and their effect on subordinates performance and satisfaction. Over twenty years Fiedler was able to develop a situational model to understand organisational effectiveness. His model combined the relationship between leadership style and favourableness of the situation. Favourableness was defined along three variables[xi];

1. The leader-member relationship,

2. The degree of task structure, and

3. The leader’s position power.

Fiedler then postulated that an effective manager diagnoses the situation along the three dimensions and then determines whether their style fits in. Thus, if leader-member relations were good, structured task orientation would be appropriate. However if their power position was weak, they might be best to apply an unstructured task orientation. If leader-member relations were poor and their power position strong, a structured task orientation could be appropriate. However if their leader-member relations were poor and power position also poor, an unstructured task orientation would be most appropriate. This model became a guide on how to structure leadership in varying situations of subordinate relationships and effective power over the group.

Rensis Likert continued his research for many years and in the mid 1960’s proposed four basic styles of leadership;

System 1: (Exploitive Autocratic) where the leader has no confidence and trust in their subordinates, subordinates do not feel free to discuss things about their job with their superior and consequently ideas and opinions on how to solve problems never reach the leader. This system is very authoritarian and tries to exploit subordinates.

System 2: (Benevolent Autocratic) where the leader has condescending confidence and trust in their subordinates, but subordinates still don’t feel free to discuss things about their job with their superior and only a few ideas ever get to the leader. This system is still authoritarian but in a paternalistic manner. However there is little delegation of tasks to subordinates.

System 3: (Participative) where the leader has substantial but not complete trust and confidence in their subordinates, so still wants to keep control of the decision making. Subordinates however feel free to discuss problems with their superior and the leader usually hears ideas about problems from their subordinates. Leadership is in a consultative style and asks for and receives input from their subordinates, but maintains the right to make the final decisions.

System 4: (Democratic) where the leader has complete confidence and trust in their subordinates in all matters, subordinates feel completely free to discuss problems and issues with their superior and ideas always reach the leader, who tries to make constructive use of them. The manager in the beginning will give some lead, but the process will become totally participative.

Likert’s research found that systems 3 and 4 were the styles that produced the best effectiveness and styles 1 and 2 produced the lowest effectiveness. Likert also recognised three forms of variables that would influence the effectiveness of leadership style within the organisation[xii];

Causal variables: independent variables that determine the direction and results of the organisation that are under control of management,

Intervening variables: reflect the internal climate of the organisation, i.e., performance goals, loyalties, attitudes, perceptions, motivations which all effect interpersonal relationships, communication and decision making in the organisation, and

End-result variables: dependent variables like the outcomes of the organisation, i.e., productivity, service, costs, quality and incomes.

Likert postulated that the style of management had very complex effects upon the organisation, where for example, a change in leadership style to system 1 may increase profits but deteriorate attitudes, loyalty and motivation, etc. In the long term these variables may lead to an erosion of profits. Thus, a change in management style may have a time lag effect before the impact of change is really felt upon the organisation. Short term cause and effects may be very different in the short term than the long term.

Likert’s work went some way in explaining leadership and the causes and effects upon and organisation and it’s employees. However it had to be recognised that each industry had a different history of development, sets and levels of skills and different procedures, so each company would require it’s own unique style of leadership.

Around the same time as Likert, William Reddin expanded upon Blake and Mouton’s model of leadership adding in personalty dispositions into their management styles. This became known as Reddin’s 3-D Model of Leadership Effectiveness. Reddin postulated that the personalty disposition of the leader could lead to either effective or ineffective leadership. Effective psychological dispositions (or archetypes) would be[xiii];

Executive: This style has a great deal of concern about both task and people. A manager using this style would be a good motivator, sets high standards, recognises individual differences and utilises team management.

Developer: This style has maximum concern for people and minimum concern for task. A manager using this style has total trust in their people and is primarily concerned with developing the best out of them.

Benevolent Autocrat: This style has maximum concern with task and minimum concern with people. A manager using this style knows exactly what is needed and goes about achieving it without causing any friction or resentment.

Bureaucrat: This style is primarily concerned with rules and procedures and maintaining control of the situation.

Ineffective psychological dispositions (or archetypes) would be;

Compromiser: This style has a great deal of concern to both task and people. This style is poor for decision making as it has difficulty taking account of all the pressures surrounding the situation, while trying to balance concerns for both task and people.

Missionary: This style gives maximum concern for people and minimum concern for task. This leader is always trying to be a ‘do gooder’ who values harmony in the end.

Autocrat: This style has maximum concern with task and minimum concern with people. The leader has no confidence in others, has an unpleasant disposition and interested only in the immediate job.

Deserter: This style has minimum concern for task and people and the leader is uninvolved and passive.

All models to date had been situation prescriptive and didn’t answer how a manager should act and what decisions should be made in a given situation. Victor Vroom and Philip Yetton developed a specific model on how decisions ought to be made (normative) that could actually be used in making decisions. Managers select a decision style according to the amount of participation in decision making that is appropriate for the situation. Vroom and Yetton outlined a number of variations according to authoritative, consultative, group based and delegative styles in making decisions, which can be either individual or with interaction with a group. A summary of the decision making choices available to the manager are[xiv];

Authoritative

a) Individual: The manager makes the decision by themselves using available information, or you obtain the necessary information from your subordinates and use it to make the decision, or,

b) Group: No group interaction or the manager obtains information from subordinates and makes the decision by themselves.

Consultative

a) Individual: The manager shares the problem with their subordinates, obtaining all their ideas and then make the decision either taking into account subordinate ideas or disregarding them.

b) Group: The manager shares the problem with their subordinates, getting their ideas without bringing them together as a group, then make a decision either taking into account subordinate ideas or disregarding them or share the problems in a group meeting and then make a decision either taking into account subordinate ideas or disregarding them.

Group Based

a) Individual: The manager shares the problem with subordinates and analyse the problem together and arrive at a consensus of opinion in a free and open environment.

Delegative

a) Individual: The manager delegates the problem to one of their subordinates providing them with all the information available and giving the subordinate authority for making the decision with the manager’s support.

b) Group: The manager shares the problem with subordinates as a group and they develop a solution. The manager acts as a coordinator of the group and willing to accept and act upon any solution the group develops consensus on.

A decision tree is used with eight situational questions where the manager would ask to determine the best style to make the decision[xv] (see figure 1.xx).

Vroom has developed this model into a computerised version and uses it in training and development programs. The model is extremely logical and provides a prescription of how managers can make decisions under varying circumstances.

The late 1980’s and 1990’s saw a change in focus of leadership to the potential a leader has and their ability to drive an organisation forward in these changing times. Contemporary leaders need to be very different from the past having to manage across cultures, through the challenge of globalisation and with the various interests of stakeholders both inside and outside the organisation. Warren Bennis is an academic who has always been able to capture the future trends of management and the environments they face and has steadily risen in popularity. In his book with Burt Nanus, they arrived at a number of common characteristics that a number of dynamic and notable contemporary leaders possess[xvi];

Leaders are able to command the attention and commitment of those that work for and with them to achieve visions,

Leaders are skilled communicators and able to cut through the multiplicity of issues and different frames people perceive, using simple signs and language,

Leaders show consistency of purpose in their dealings with colleagues and various constituencies they deal with, creating a sense of trust, and

Leaders are able to identify their own strengths and weaknesses and use this knowledge to their advantage.

Bennis and Nanus see a vast contrast between a leader and a manager;

Managers administrate and leaders innovate,

Managers are copies of each other and leaders are unique and original,

Managers stabilise and sustain while leaders develop,

Managers focus on structure and process while the leader on people,

Managers rely on control and leaders on trust,

Managers have short-term goals and leaders long range,

Managers ask ‘How’ and ‘when’ and leaders ‘what’ and ‘why’,

Managers are concerned with profits and leaders a vision,

Managers accept the status quo and leaders challenge it,

Managers are followers and leaders their own person, and

Managers do things right and leaders do the right thing.

Bennis and Nanus conclude that business needs a new generation of leaders and not managers. It is the leader who will be able to deal with volatility, turbulence and ambiguity in the future, rather than the manager. Bennis’s ideas set the momentum of the new management paradigm going, which has been followed by a number of authors putting various slants on their arguments.

Warren Bennis

At the same time, the concept of the transformational leader was developed as a leader who a) is able to raise the consciousness about the importance of outcomes, b) shows the value and benefits of focusing on the groups’ rather than individual interests, and c) raises their employees needs levels so they value challenges, responsibility and growth[xvii]. In the early 1990’s the superleader went beyond the transformational leader by helping their followers discover their own abilities and grow[xviii]. The superleader empowers followers to contribute fully to the organisation and develops self-leaders who take over responsibility for their own self motivation and personal behaviours[xix].

Wells saw leadership roles in a number of paradigms as a way of explaining various organisational roles[xx];

Sages: Expanding their knowledge about many subjects to improve strategy development,

Visionaries: Inspiring people to go beyond their previous accomplishments,

Magicians: Bringing change through bridging the gap between where the organisation is now and where it wants to go,

Globalists: Coordinating the experiences of people from various cultures, seeing diversity as a strength,

Mentors: Helping employees advance in their careers and bringing them to their potential,

Allies: Building up effective teams and alliances,

Sovereigns: Taking responsibility for all decisions,

Guides: Stating principals clearly so all can understand and develop commitment, and

Artisans: Trying to improve performance by ensuring the quality of the company’s products and production processes.

Click on subscribe so articles can be directly emailed to your inbox:

References:

[i] Smart, N., (1999), World Philosophies, New York, Routledge.

[ii] Jay, A., (1970), Management and Machiavelli, New York, Penguin, P. 70.

[iii] Jay, A., (1970), op. cit., pp. 26-27.

[iv] Mintzberg, H., (1983), Power In and Around Organizations, Englewood Cliffs, NJ., Prentice-Hall.

[v] Shackleton, D., Pitt, L. and Marks, A., S., (1990), ‘Managerial decision styles and Machiavellianism: A comparative study’, Journal of Managerial Psychology, 5 (1), pp. 10-15.

[vi] Donaldson, P., S., (1989), Machiavelli and Mystery of State, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

[vii] Lewin, K., Lippitt, R. and White, R., K., (1939), ‘Patterns of Aggressive Behavior in Experimentally Created Social Climates’, Journal of Social Psychology, May, pp. 271-276.

[viii] Likert, R., (1950), ‘Forward’, in Katz, D., Maccoby, N. and Morse, N., C., Productivity, Supervision and Morale in an Office Situation, University of Michigan; Survey Research Centre, Ann Arbor.

[ix] Stogdill, R., M. and Coons, A., E., (Eds.), (1957), Leader Behavior: It’s Description and Measurement, Columbus, Ohio State University, Bureau of Business Research.

[x] Blake, R., R. and Mouton, J., S. (1966), ‘Managerial Façades’, Advanced Management Journal, July.

[xi] Fiedler, F., E., (1967), A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[xii] Likert, R., (1967), The Human Organization, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[xiii] Reddin, W., J. (1970), Managerial Effectiveness, New York, McGraw-Hill.

[xiv] Vroom, V., H. and Jago, A., G., (1974),‘Decision-making as a social process: Normative and descriptive models of leader behaviour’, Decision Sciences, P. 745.

[xv] Vroom, V., H., (1973), ‘A New Look at Managerial Decision Making’, Organizational Dynamics, 1, (4), pp. 67.

[xvi] Bennis, W. and Nanus, B., (1985), The Strategies for Taking Charge, New York, Harper & Row.

[xvii] Bass, B., M., (1985), ‘Leadership, Good, Better, Best,’, Organizational Dynamics, 13, (3), pp. 26-40.

[xviii]Manz, C., C. and Sims, H., P., Jr. (1991), ‘Superleadership: Beyond the myth of leadership’,Organizational Dynamics, 19, (4), pp. 18-35.

[xix] Manz, C., C. and Sims, H., P., Jr. (1989), Superleadership: Leading Others to Lead Themselves, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall.

[xx] Wells, S, (1996), From Sage to Artisan: The Nine Roles of the Value-Driven Leader, Palo Alto, CA., Davies-Black.